Blah voyage

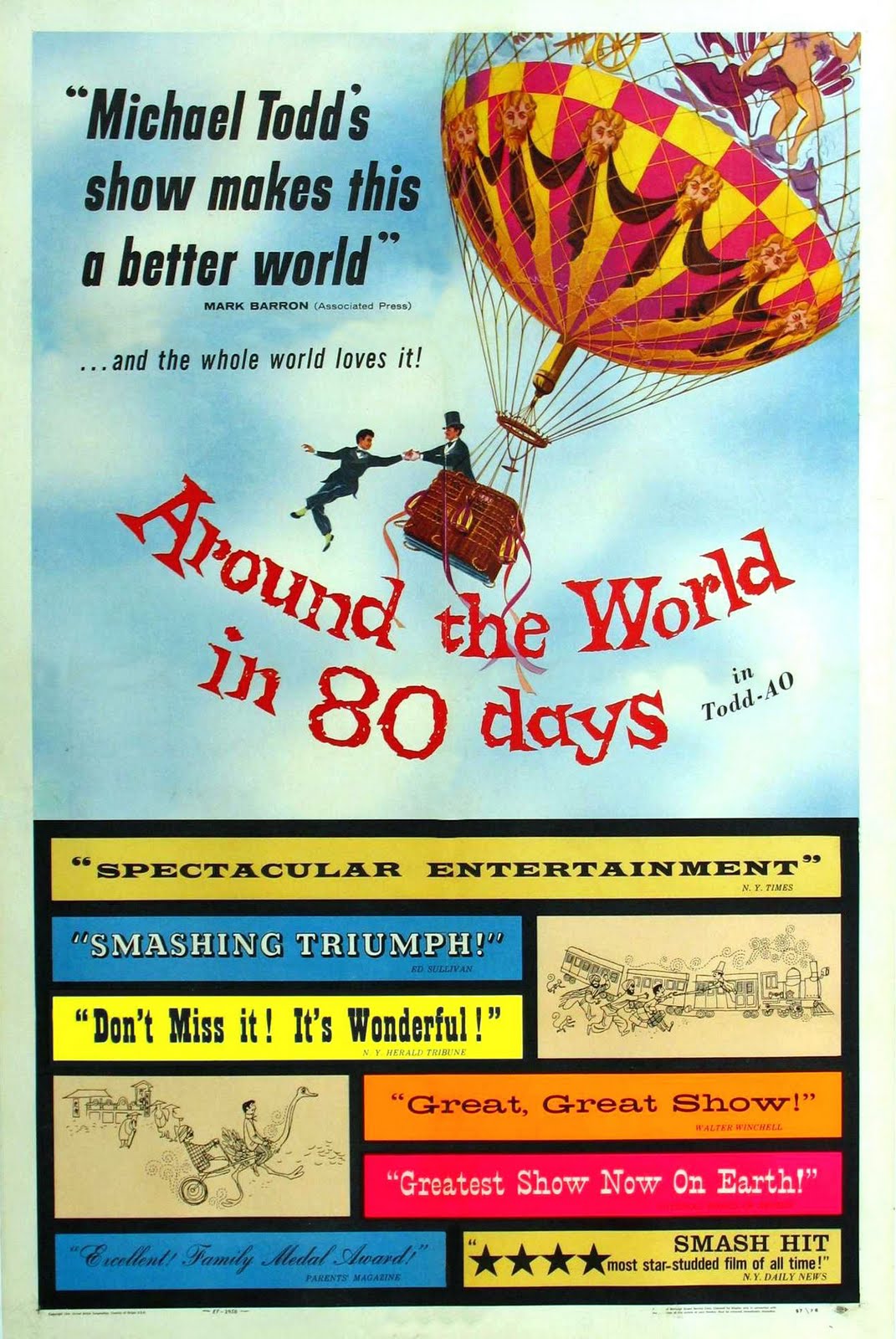

There's a stock complaint about the Academy Awards that goes something to the effect of: "they don't give Oscars for the Best Picture [Editing, Costume Design, etc.], they give Oscars for the Most Picture." That's usually at least a little bit true, but it becomes especially, spectacularly, in-your-face true in the case of 1956's Around the World in 80 Days, which is quite possibly the most picture to ever take the Academy's top prize. It won four other awards (Screenplay, Cinematography, Editing, Score), and was nominated for three beyond that (Director, Art Direction, Costume Design), but it is entirely and utterly a sterling example of the producer's art; the film exists in the form it does, or any form at all really, because theater impresario Mike Todd was willing to throw as much money and resources at his first and only narrative feature film as it took to get it exactly right. "Exactly right" being a term that need to go in some might aggressive scare quotes; what was right for Todd did not necessarily have any meaningful correlation to what was right for artistry. But I'll say this on the film's behalf: there's no doubt at all that you get your money's worth, and you see every penny of its extremely generous budget onscreen. Even when you may not wish to.

The film is officially an adaptation of Jules Verne's 1873 novel, and with one fairly large exception, it's a pretty faithful adaptation, at that. But what it really is, is the spiritual successor to 1952's This Is Cinerama, another Todd-produced film. Using his experience in creating successful theatrical spectacles, he co-founded Cinerama in 1950, helping financially and artistically to breathe life into inventor Fred Waller's idea for a three-strip widescreen process. This Is Cinerama is not a film; it's an advertisement. It consists in its entirety of disconnected snapshots of the world, telling no story and building no argument, unless that argument should be that the world looks a whole lot more exciting when it's being projected on a curved screen the size of an office building. Todd abandoned Cinerama fairly early; the limitations of a three-strip widescreen system were obvious from the start, and in 1953 he teamed with brothers Robert and Marshall Naify (owners of the United Artists theater chain) and the American Optical Company to create the Todd-AO system, a state-of-the-art 70mm film and high-fidelity sound standard. The first film released using Todd-AO was the 1955 adaptation of the musical Oklahoma! (a show Todd had declined to stage on Broadway, seeing little commercial prospects for something so un-glitzy), but Todd himself had nothing to do with that film directly. Thus Around the World in 80 Days became the first deliberate showpiece for the system.

It follows the This Is Cinerama template surprisingly closely, given that this is a narrative film and that was a series of disconnect travel footage. First and more gruelingly, there's the prologue, something that the already very bloated movie (182 minutes, including the intermission and exit music) needs not at all: in a tiny 1.37:1 box in the middle of the frame, serious television journalist Edward R. Murrow appears in a serious-looking library to tell us about the history of Verne, a fabulist in his day whose predictions came very true in many ways. For example (says Murrow), Verne wrote From the Earth to the Moon in 1865, and this seemed magical nonsense at the time. But the movies saw the potential, which is why in 1902, Georges Méliès made the loose adaptation A Trip to the Moon (Murrow here gives me the collywobbles by pronouncing the director's name as "Malay"). And then we watch a couple two, three minutes of A Trip to the Moon, scored by an edited version of "An American in Paris", while Murrow narrates. After this, Murrow points out that both Verne and Méliès would have been delighted to see our own modern rockets, by which we might someday make our own trip to the moon: we first see one of these in the same 1.37:1 box, but then the frame opens up on the top and bottom to film the whole luxurious 2.20:1 Todd-AO frame as the launch commences - exactly the same trick that shows up in This Is Cinerama. And we then glide seamlessly - only, like, the opposite of seamless - into the film's recreation of Victorian London, which spills out all over the frame in a wide-angle shoot that makes it look disgustingly bulbous (at this point, Todd-AO was designed to be shown on curved scree , which presumably would have made this look better). Also, as a military band marches towards us playing its instruments, the sound passes from the front speakers to the sides to the back, because this was also showing off a sound system, don't forget. The one pity is that all of this is in 24 frames per second; Todd-AO was, initially, a 30 FPS system, but 24 FPS versions of both this and Oklahoma! were shot for distribution purposes - for Oklahoma! this meant shooting the whole film twice, once as Todd-AO, once as CinemaScope, while for Around the World it meant shooting it from two cameras next to each other, both using the Todd-AO printing and sound technologies. And, of course, barring very special retrospective screenings, the 24 FPS version of the film is the only one available these days, which means that aside from everything else, the camera is slightly to the side of center in every shot. You can tell.

Anyway, at long last, we're ready to get into the movie, which again, basically follows Verne: neurotically punctual Phileas Fogg (David Niven, in a role he fought for hard and claimed to be one of his favorites ever after) gets into a slightly heated argument with the members of his club that the recently-completed trans-Indian railroads means that the world has gotten so small that a well-prepared traveler could circumnavigate it in 80 days. Eventually, a princely sum of £20,000 is laid as a bet on the matter, and by the end of the day, Fogg is already on the way to France with his newly-hired valet Passepartout (Mexican superstar Mario Moreno, AKA "Cantinflas", by some reckonings the most popular movie star in the world at this time, making the first of his very few films in English). The travel by balloon, by yacht, by train, picking up a suspicious London police detective named Fix (Robert Newton) in Suez - he's convinced that Fogg is the thief who has recently stolen £55,000 from the Bank of England - and a princess named Aouda (Shirley MacLaine) in India, while Fogg spends money hand over fist to jerry-rig one connection after another, miraculously always keeping to his tight schedule, while back in London, people from every level of society are making increasingly frenzied bets on his success.

Honestly, as an adventurous travelogue, Around the World in 80 Days is actually solid. Or rather, it has solidity within it. Cantinflas is irritating as hell with his mugging, broad-as-a-barn-door shtick; MacLaine is mortifyingly miscast both as an Indian and as royalty, and she knew it, and her whole performance is enormously shy and quiet and confused; Newton was fighting to stay sober the entire shoot, and ends up simply receding into himself. But Niven is having a grand time, enough to make up for all three of his co-stars, amping up his usual stereotypical prim British stolidity to goofy comic levels and being a hambone like I've never seen elsewhere in his career (in a film where literally every character is a national or ethnic stereotype, he's one of only two where it feels like a deliberate comic choice and not just laziness. The other is John Carradine camping it up as a U.S. military man, and that's largely just Carradine being himself). He's a charming travel companion, if not much more.

More importantly, it's obvious that a tremendous amount of money was spent on the film. The wall-to-wall location footage isn't always well-served by the wide-angle lenses, or the Cinerama-esque insistence on forward tracking shots that draw attention to the distortion, but they sure are sprawling and gorgeous - the aerial shots of the French countryside especially, though the establishing shots of Yokohama look pretty fantastic as well. And my goodness, but there are a lot of them. You could pretty easily cut Around the World by half an hour just by removing the narratively inconsequential establishing shots, I suspect.

Which brings us back to the problem of bloat. It's a huge movie, and it refuses to let you forget it. A huge number of locations, a huge number of extras, a huge number of celebrity cameos - this was, in fact, the film where the phrase "cameo" was coined to describe a brief appearance by a very famous person. Most of them aren't even distracting! Only Frank Sinatra's unspeaking role as a San Francisco piano player is really destructive, mostly because the camera keeps staring at his back in multiple shots. Though I'll admit to spending too many seconds puzzling over whether Peter Lorre was meant to be Japanese or not.

At any rate, huge amounts of everything, and all of it crammed into the film with an eye toward quantity over curation. It is a huffing, puffing, extravagantly slow movie, in which even eye-popping spectacle grows boring as a result of being incorporated so indifferently. Director Michael Anderson is shepherding then film more than creating it, and there's absolutely no sense of artistic personality, or any judgment at all really; just thing after thing after thing. Poor MacLaine, already giving the film's worst lead performance, is made to look even worse by the film's bizarre insistence on burying her in the back of wide shots for her first several appearances in the movie; she barely even emerges as a character until she's already been in the movie for 15 minutes or so. That kind of lack of judgment. The film needs to be Big; so Big it shall be, forever and always.

For landscape photography, that approach works. For storytelling, not so much. The whole film feels like it was made without any choices going into it: everything from Lionel Lindon's cinematography to Ken Adam's production design to Victor Young's score (which hangs a broadly stereotypical national musical cue on every situation - "Rule Brittania" for Fogg, "La Cucaracha" for Passepartout, stock motifs for everything else from a Spanish bullfight to a Western American train ride - mostly to serve as a roadmap through the sheer glut of content; there's also a chiming waltz motif meant to suggest "around the world" itself that is, I think, the only actual original composition. It is, to be fair, lovely) seems formulated according to a set of engineering instructions rather than artistic inspiration. It is a film that feels managed into existence to fulfill a very specific goal of constant maximalism. I can say, at least, that it looks astonishing and overwhelming, and I can absolutely see why it made such a splash when it was new and unlike anything else out there. It's still unlike anything else out there, really. And good Lord, is it ever exhausting.

The film is officially an adaptation of Jules Verne's 1873 novel, and with one fairly large exception, it's a pretty faithful adaptation, at that. But what it really is, is the spiritual successor to 1952's This Is Cinerama, another Todd-produced film. Using his experience in creating successful theatrical spectacles, he co-founded Cinerama in 1950, helping financially and artistically to breathe life into inventor Fred Waller's idea for a three-strip widescreen process. This Is Cinerama is not a film; it's an advertisement. It consists in its entirety of disconnected snapshots of the world, telling no story and building no argument, unless that argument should be that the world looks a whole lot more exciting when it's being projected on a curved screen the size of an office building. Todd abandoned Cinerama fairly early; the limitations of a three-strip widescreen system were obvious from the start, and in 1953 he teamed with brothers Robert and Marshall Naify (owners of the United Artists theater chain) and the American Optical Company to create the Todd-AO system, a state-of-the-art 70mm film and high-fidelity sound standard. The first film released using Todd-AO was the 1955 adaptation of the musical Oklahoma! (a show Todd had declined to stage on Broadway, seeing little commercial prospects for something so un-glitzy), but Todd himself had nothing to do with that film directly. Thus Around the World in 80 Days became the first deliberate showpiece for the system.

It follows the This Is Cinerama template surprisingly closely, given that this is a narrative film and that was a series of disconnect travel footage. First and more gruelingly, there's the prologue, something that the already very bloated movie (182 minutes, including the intermission and exit music) needs not at all: in a tiny 1.37:1 box in the middle of the frame, serious television journalist Edward R. Murrow appears in a serious-looking library to tell us about the history of Verne, a fabulist in his day whose predictions came very true in many ways. For example (says Murrow), Verne wrote From the Earth to the Moon in 1865, and this seemed magical nonsense at the time. But the movies saw the potential, which is why in 1902, Georges Méliès made the loose adaptation A Trip to the Moon (Murrow here gives me the collywobbles by pronouncing the director's name as "Malay"). And then we watch a couple two, three minutes of A Trip to the Moon, scored by an edited version of "An American in Paris", while Murrow narrates. After this, Murrow points out that both Verne and Méliès would have been delighted to see our own modern rockets, by which we might someday make our own trip to the moon: we first see one of these in the same 1.37:1 box, but then the frame opens up on the top and bottom to film the whole luxurious 2.20:1 Todd-AO frame as the launch commences - exactly the same trick that shows up in This Is Cinerama. And we then glide seamlessly - only, like, the opposite of seamless - into the film's recreation of Victorian London, which spills out all over the frame in a wide-angle shoot that makes it look disgustingly bulbous (at this point, Todd-AO was designed to be shown on curved scree , which presumably would have made this look better). Also, as a military band marches towards us playing its instruments, the sound passes from the front speakers to the sides to the back, because this was also showing off a sound system, don't forget. The one pity is that all of this is in 24 frames per second; Todd-AO was, initially, a 30 FPS system, but 24 FPS versions of both this and Oklahoma! were shot for distribution purposes - for Oklahoma! this meant shooting the whole film twice, once as Todd-AO, once as CinemaScope, while for Around the World it meant shooting it from two cameras next to each other, both using the Todd-AO printing and sound technologies. And, of course, barring very special retrospective screenings, the 24 FPS version of the film is the only one available these days, which means that aside from everything else, the camera is slightly to the side of center in every shot. You can tell.

Anyway, at long last, we're ready to get into the movie, which again, basically follows Verne: neurotically punctual Phileas Fogg (David Niven, in a role he fought for hard and claimed to be one of his favorites ever after) gets into a slightly heated argument with the members of his club that the recently-completed trans-Indian railroads means that the world has gotten so small that a well-prepared traveler could circumnavigate it in 80 days. Eventually, a princely sum of £20,000 is laid as a bet on the matter, and by the end of the day, Fogg is already on the way to France with his newly-hired valet Passepartout (Mexican superstar Mario Moreno, AKA "Cantinflas", by some reckonings the most popular movie star in the world at this time, making the first of his very few films in English). The travel by balloon, by yacht, by train, picking up a suspicious London police detective named Fix (Robert Newton) in Suez - he's convinced that Fogg is the thief who has recently stolen £55,000 from the Bank of England - and a princess named Aouda (Shirley MacLaine) in India, while Fogg spends money hand over fist to jerry-rig one connection after another, miraculously always keeping to his tight schedule, while back in London, people from every level of society are making increasingly frenzied bets on his success.

Honestly, as an adventurous travelogue, Around the World in 80 Days is actually solid. Or rather, it has solidity within it. Cantinflas is irritating as hell with his mugging, broad-as-a-barn-door shtick; MacLaine is mortifyingly miscast both as an Indian and as royalty, and she knew it, and her whole performance is enormously shy and quiet and confused; Newton was fighting to stay sober the entire shoot, and ends up simply receding into himself. But Niven is having a grand time, enough to make up for all three of his co-stars, amping up his usual stereotypical prim British stolidity to goofy comic levels and being a hambone like I've never seen elsewhere in his career (in a film where literally every character is a national or ethnic stereotype, he's one of only two where it feels like a deliberate comic choice and not just laziness. The other is John Carradine camping it up as a U.S. military man, and that's largely just Carradine being himself). He's a charming travel companion, if not much more.

More importantly, it's obvious that a tremendous amount of money was spent on the film. The wall-to-wall location footage isn't always well-served by the wide-angle lenses, or the Cinerama-esque insistence on forward tracking shots that draw attention to the distortion, but they sure are sprawling and gorgeous - the aerial shots of the French countryside especially, though the establishing shots of Yokohama look pretty fantastic as well. And my goodness, but there are a lot of them. You could pretty easily cut Around the World by half an hour just by removing the narratively inconsequential establishing shots, I suspect.

Which brings us back to the problem of bloat. It's a huge movie, and it refuses to let you forget it. A huge number of locations, a huge number of extras, a huge number of celebrity cameos - this was, in fact, the film where the phrase "cameo" was coined to describe a brief appearance by a very famous person. Most of them aren't even distracting! Only Frank Sinatra's unspeaking role as a San Francisco piano player is really destructive, mostly because the camera keeps staring at his back in multiple shots. Though I'll admit to spending too many seconds puzzling over whether Peter Lorre was meant to be Japanese or not.

At any rate, huge amounts of everything, and all of it crammed into the film with an eye toward quantity over curation. It is a huffing, puffing, extravagantly slow movie, in which even eye-popping spectacle grows boring as a result of being incorporated so indifferently. Director Michael Anderson is shepherding then film more than creating it, and there's absolutely no sense of artistic personality, or any judgment at all really; just thing after thing after thing. Poor MacLaine, already giving the film's worst lead performance, is made to look even worse by the film's bizarre insistence on burying her in the back of wide shots for her first several appearances in the movie; she barely even emerges as a character until she's already been in the movie for 15 minutes or so. That kind of lack of judgment. The film needs to be Big; so Big it shall be, forever and always.

For landscape photography, that approach works. For storytelling, not so much. The whole film feels like it was made without any choices going into it: everything from Lionel Lindon's cinematography to Ken Adam's production design to Victor Young's score (which hangs a broadly stereotypical national musical cue on every situation - "Rule Brittania" for Fogg, "La Cucaracha" for Passepartout, stock motifs for everything else from a Spanish bullfight to a Western American train ride - mostly to serve as a roadmap through the sheer glut of content; there's also a chiming waltz motif meant to suggest "around the world" itself that is, I think, the only actual original composition. It is, to be fair, lovely) seems formulated according to a set of engineering instructions rather than artistic inspiration. It is a film that feels managed into existence to fulfill a very specific goal of constant maximalism. I can say, at least, that it looks astonishing and overwhelming, and I can absolutely see why it made such a splash when it was new and unlike anything else out there. It's still unlike anything else out there, really. And good Lord, is it ever exhausting.