Salvage love

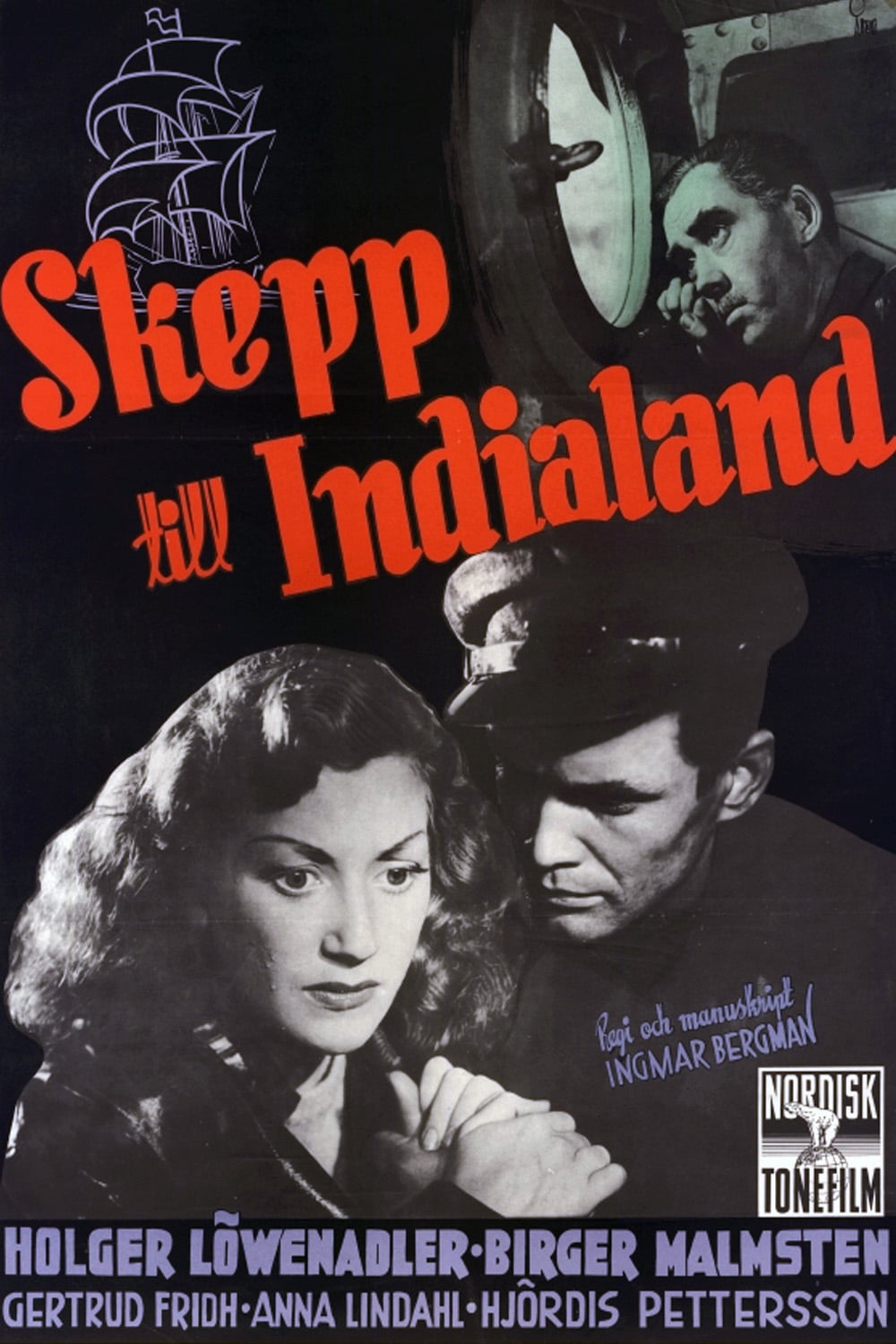

Later in life,when Ingmar Bergman would speak of his earliest films, it was generally to crap all over them. It seems to me that, within that cluster of movies, 1947's A Ship to India (adapted from a play by Martin Söderhjelm) is the one that he would discuss with the most open hostility, referring to it as "disastrous". I suspect there's a little bit of shame involved with that: earlier in life, he considered this to be the first of his movies that was actually successful, enough for him to fight for it against the producer, Lorens Marmstedt, who was unhappy with the first cut. Now, we all have heard the name of Ingmar Bergman and I'll bet almost none of us, including me, have heard the name of Lorens Marmstedt, so we all know who won in the long term. But in this case, honestly, I'm going to have to side with Marmstedt: I don't know what necessarily would have fixed A Ship to India, but I do know that it needed fixing. We're three films into Bergman's career at this point, and each one of them has been worse than the one before; the nicest thing one can say is that he's constantly trying out new approaches, and failing in new ways.

One of the chief sources of failure this time around is a cumbersome, unnecessary framing narrative. Johannes Blom (Birger Malmsten, the male lead from the previous year's It Rain on Our Love, who thus becomes the first major returning actor in a Bergman film) has just returned to his hometown after seven years at sea. The first thing we learn about him is that he's obsessed to the point of distraction with a woman named "Sally", who he thinks he spots on the dark, misty streets. And this will have a great deal to do with the rest of the film. The second is that he has a good relationship with Sofi (Hjördis Petterson) and Selma (Naemi Briese), the proprietors of a rooming house that's hist first stop. And this will have nothing to do with the rest of the film. We could maybe forgive it if the point here was to create a sense of depth and color, but Johannes ends up as such a callow, reactive character that any time spent building up his backstory that doesn't directly feed into the drama is time wasted. Anyway, Slema and Sofi are currently housing none other than Sally herself (Gertrud Fridh), who has collapsed into self-hatred since Johannes saw her last, seven years ago; despondent, he runs out to the shore, throwing himself weeping to the stones, and flashing back to what, exactly, happened between them.

I honestly can't think of a single thing the flashback structure does for the film, other than give it sense of fatalism; this is, by some margin, Bergman's grimmest film up to this point. It also muddies up considerably what the story is about, and even who: it's hard to get this far without expecting Johannes to be the protagonist, but it ends up being a four-way character study, and he's the least interesting of the four. The situation, seven years in the past, is that Johannes - still with a prominent hunched back that worked itself out sometime in the interim - is part of the family salvage business. His father, Captain Alexander Blom (Holger Löwenadler) has run the same ship for more than a quarter of a century, aided by his longsuffering wife Alice (Anna Lindahl), and since then with an expanding crew. Alexander is also, not to put to fine a point on it, a giant asshole, who has never done a particularly good job of hiding his dislike of his his crippled son, nor of tempering the authoritarian zeal with which he runs his crew. Lately, he's been coping with a diagnosis of impending blindness by burying himself in drink and licentious; he has lately fallen in lust with Sally, a headliner at a local variety theater, and has decided to rub everybody's noses in this by bringing her to live on the boat with him and his family and crew. Sally has tolerated this mostly as a way of getting away from the dissolute, uncertain life of the theater, and she obviously likes Johannes more than his father.

The bulk of the film consists of stepping back to watch how this volatile situation develops. Like Bergman's first film, Crisis, it takes the material of a sudsy melodrama and strips it down to its human elements; unlike Crisis, it doesn't do this with any persistent success. There are good scenes in the film, even a great one: Alice, lying in the bunk over Alexander, quietly reminds him of the amount of work she has poured into their marriage, reflecting ruefully on how she used to pump air to him as he worked underwater. Her conversation is filmed from an impossible angle, where the wall of the berth ought to be, and this gives it a bit of uncanny impact; later, she sits upright, with a streak of light across her face, reciting her feelings about her marriage in an almost trancelike state. As the scene progresses, the actors move around until he looms behind her in the midground, as she continues to quietly assert her pain at being betrayed so often and in so many ways over their marriage, talking about him to the universe, with no real hope of actually getting through to him. The whole scene is superb, and it represents the first time in a Bergman film that he demonstrates the faith in the human face that will ultimately become one of the defining traits of his style.

Nothing else in the film comes close to matching that, but there are moments that feel at least like the work of a thoughtful filmmaking team: a scene set backstage at the variety theater, in which Bergman the theater director comes to the fore to showcase the orderly chaos just behind the curtain, with the mixture of bored, nervous, and impish actors and stagehands sprawling across the entire depth of the frame and out of it; the first time Johannes and Sally have sex, a lovely bit of tender innuendo and ellipsis that doesn't try to overburden us with the idea that they're already deeply in love with each other. And Alexander is a fairly well-defined character, hostile enough that we automatically take everybody else's side, but pathetic enough in his terror of getting old that we can't write him off as a simple monster.

In general, though, this is all fairly perfunctory and emotionally stunted. All the characters besides Alexander are primarily reactive, which makes it hard to understand them very well, or even care; Johannes especially is basically just a set of reflexes, moving away from his tyrannical father without ever being clear what he wants, despite the special pleading of the monologue that gives the film its title. Stylistically, while Göran Strindberg's cinematography is quite lovely in its sleek high contrast, it's not really doing anything, and the sometimes elaborate camera movements (including a very striking crane shot over a carnival) feel more like the work of filmmakers nervously attempting to force some verve and pizzazz into their movie, rather than filmmakers who know what they want to do with our attention and how they want to move us through their film. It's unfocused filmmaking for a flat and occasionally banal scenario; one would love to say that this is all acceptable as part of Bergman's ongoing learning curve as a young director, but from the evidence at this point in his career, it's not entirely clear what he's learning.

One of the chief sources of failure this time around is a cumbersome, unnecessary framing narrative. Johannes Blom (Birger Malmsten, the male lead from the previous year's It Rain on Our Love, who thus becomes the first major returning actor in a Bergman film) has just returned to his hometown after seven years at sea. The first thing we learn about him is that he's obsessed to the point of distraction with a woman named "Sally", who he thinks he spots on the dark, misty streets. And this will have a great deal to do with the rest of the film. The second is that he has a good relationship with Sofi (Hjördis Petterson) and Selma (Naemi Briese), the proprietors of a rooming house that's hist first stop. And this will have nothing to do with the rest of the film. We could maybe forgive it if the point here was to create a sense of depth and color, but Johannes ends up as such a callow, reactive character that any time spent building up his backstory that doesn't directly feed into the drama is time wasted. Anyway, Slema and Sofi are currently housing none other than Sally herself (Gertrud Fridh), who has collapsed into self-hatred since Johannes saw her last, seven years ago; despondent, he runs out to the shore, throwing himself weeping to the stones, and flashing back to what, exactly, happened between them.

I honestly can't think of a single thing the flashback structure does for the film, other than give it sense of fatalism; this is, by some margin, Bergman's grimmest film up to this point. It also muddies up considerably what the story is about, and even who: it's hard to get this far without expecting Johannes to be the protagonist, but it ends up being a four-way character study, and he's the least interesting of the four. The situation, seven years in the past, is that Johannes - still with a prominent hunched back that worked itself out sometime in the interim - is part of the family salvage business. His father, Captain Alexander Blom (Holger Löwenadler) has run the same ship for more than a quarter of a century, aided by his longsuffering wife Alice (Anna Lindahl), and since then with an expanding crew. Alexander is also, not to put to fine a point on it, a giant asshole, who has never done a particularly good job of hiding his dislike of his his crippled son, nor of tempering the authoritarian zeal with which he runs his crew. Lately, he's been coping with a diagnosis of impending blindness by burying himself in drink and licentious; he has lately fallen in lust with Sally, a headliner at a local variety theater, and has decided to rub everybody's noses in this by bringing her to live on the boat with him and his family and crew. Sally has tolerated this mostly as a way of getting away from the dissolute, uncertain life of the theater, and she obviously likes Johannes more than his father.

The bulk of the film consists of stepping back to watch how this volatile situation develops. Like Bergman's first film, Crisis, it takes the material of a sudsy melodrama and strips it down to its human elements; unlike Crisis, it doesn't do this with any persistent success. There are good scenes in the film, even a great one: Alice, lying in the bunk over Alexander, quietly reminds him of the amount of work she has poured into their marriage, reflecting ruefully on how she used to pump air to him as he worked underwater. Her conversation is filmed from an impossible angle, where the wall of the berth ought to be, and this gives it a bit of uncanny impact; later, she sits upright, with a streak of light across her face, reciting her feelings about her marriage in an almost trancelike state. As the scene progresses, the actors move around until he looms behind her in the midground, as she continues to quietly assert her pain at being betrayed so often and in so many ways over their marriage, talking about him to the universe, with no real hope of actually getting through to him. The whole scene is superb, and it represents the first time in a Bergman film that he demonstrates the faith in the human face that will ultimately become one of the defining traits of his style.

Nothing else in the film comes close to matching that, but there are moments that feel at least like the work of a thoughtful filmmaking team: a scene set backstage at the variety theater, in which Bergman the theater director comes to the fore to showcase the orderly chaos just behind the curtain, with the mixture of bored, nervous, and impish actors and stagehands sprawling across the entire depth of the frame and out of it; the first time Johannes and Sally have sex, a lovely bit of tender innuendo and ellipsis that doesn't try to overburden us with the idea that they're already deeply in love with each other. And Alexander is a fairly well-defined character, hostile enough that we automatically take everybody else's side, but pathetic enough in his terror of getting old that we can't write him off as a simple monster.

In general, though, this is all fairly perfunctory and emotionally stunted. All the characters besides Alexander are primarily reactive, which makes it hard to understand them very well, or even care; Johannes especially is basically just a set of reflexes, moving away from his tyrannical father without ever being clear what he wants, despite the special pleading of the monologue that gives the film its title. Stylistically, while Göran Strindberg's cinematography is quite lovely in its sleek high contrast, it's not really doing anything, and the sometimes elaborate camera movements (including a very striking crane shot over a carnival) feel more like the work of filmmakers nervously attempting to force some verve and pizzazz into their movie, rather than filmmakers who know what they want to do with our attention and how they want to move us through their film. It's unfocused filmmaking for a flat and occasionally banal scenario; one would love to say that this is all acceptable as part of Bergman's ongoing learning curve as a young director, but from the evidence at this point in his career, it's not entirely clear what he's learning.