He's my brother

A review requested by WBTN, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Francis Ford Coppola's popular reputation lies almost exclusively on the four films he made during the 1970s, every one an instantly-canonised masterpiece: 1972's The Godfather, 1974's The Conversation and The Godfather, Part II, 1979's Apocalypse Now. But for myself, I'm coming around to the idea that his subsequent run of movie in the 1980s is much more interesting. "Interesting" is not, of course, a synonym for "good". Still, there's something incredibly compelling about how Coppola dealt with the collapse of his production company and his directorial career following the disastrous failure of the brilliant, beautiful, insanely dysfunctional musical One from the Heart, from 1981. That film put him in director jail as hard as any multiple-Oscar winner ever has been so imprisoned, and for the next two decades, his career is a patchwork of very effortful attempts to be a Good Boy and make nice, commercially-sound genre pictures and weird indulgences where those attempts go spectacularly awry, resulting in something far more aggressively experimental than anything he was up to during his ostensible heyday.

We have now one of the weird indulgences in the form of Rumble Fish, the director's second feature released in 1983, and a film nearly as bold in its refusal to follow the rules as One from the Heart itself. The difference being that, at its strongest, One from the Heart is a glorious mess, while Rumble Fish spends its first act arguing for itself as the best film of Coppola's career. It doesn't stay at that level, but no matter how far it falls off, it's creative and challenging at a level that '80s American cinema barely knew how to work with. It's impossible not to compare it to his earlier 1983 film, The Outsiders: both are adaptations of novels by S.E. Hinton (she co-wrote the screenplay for this one with the director), both are set in Oklahoma and tell stories of teenage gang members with more of a focus on lyricism than crime. The biggest difference is that The Outsiders is basically a normal movie made with a fair level of craft, and for this it was one of the few films Coppola made in the '80s to turn a profit.

Rumble Fish, meanwhile, freaked out all of Hollywood, nearly got Coppola fired from The Cotton Club by producer Robert Evans, and only recouped a quarter of its production budget. I hate to say something as snotty as "this is because it was too good for audiences", but that's sort of exactly what's going on. That this and The Outsiders could come out right on top of each other, touching on the same milieu, and this is the one that tanked, does not make one feel especially good. Rumble Fish is an extraordinarily bold experiment in pretty much everything: the sleek high-contrast cinematography by Stephen H. Burum, the loose editing by Barry Malkin (it has a stunningly free feeling that I'd almost like to call "improvisational", as though the film was responding to stimuli along with the viewer rather than choosing stimuli for us), the heavily stylised performances, the unnaturalistic dialogue. Above all else, it's experimenting with the music by Stewart Copeland, drummer for The Police, who has accordingly provided the movie with an unusual percussive score: it's lilting and fairy-like at some points, action-heavy and driving at others, but in all instances, it's marked out by how goddamn exhausting it is to listen to: it's unrelenting, over-present in the sound mix, rhythmic at an uncomfortably fast past, and all in all does an ingenious job of getting the heart racing in a way that makes it very easy for all of the other stylisation to hit the viewer in a state of heightened sensitivity.

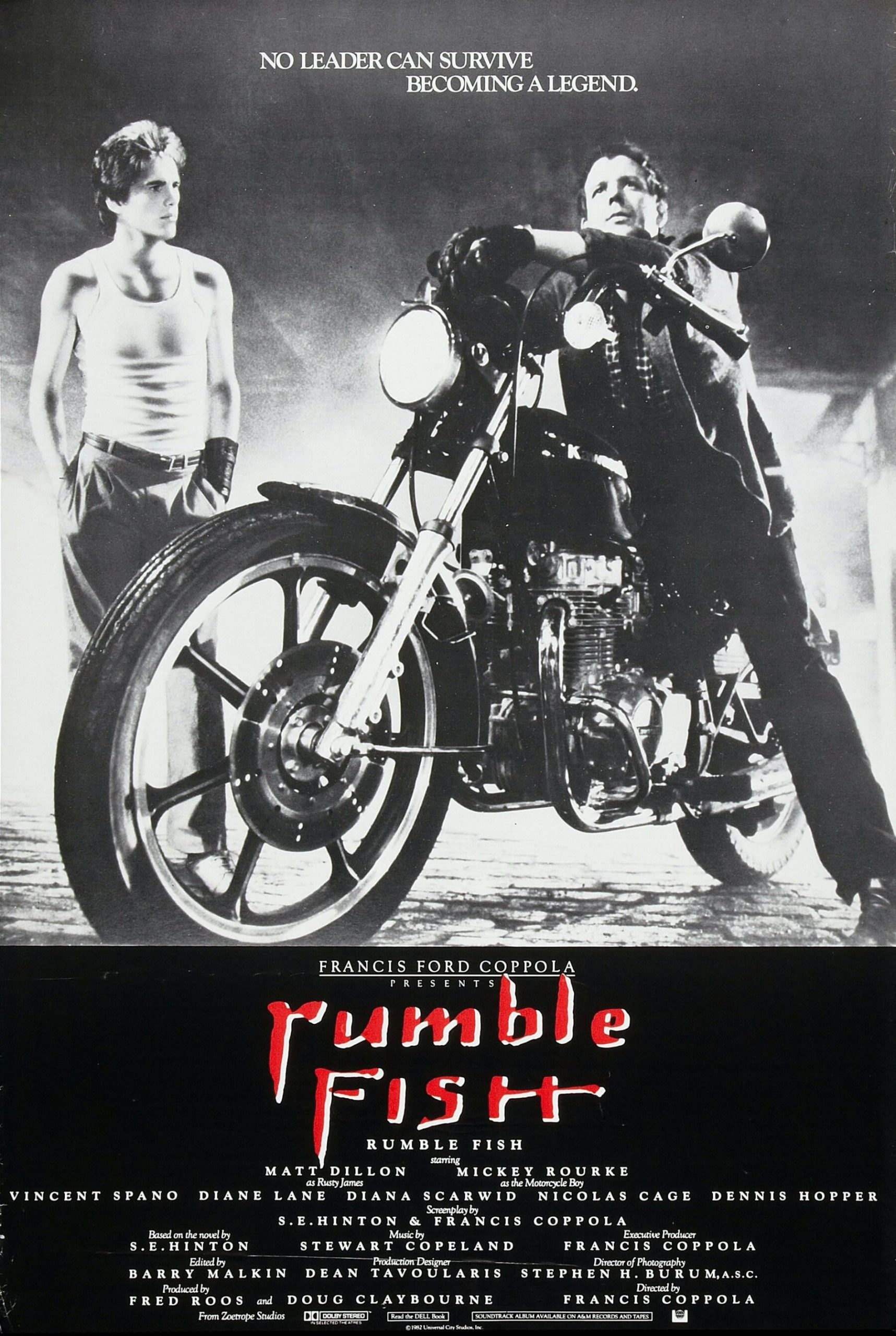

The plot hangs on a relationship between a teenager and his absent older brother, which already starts to get us to the reasons why Coppola treats the thing so strangely. Rusty James (Matt Dillon) is a member of one of two rival gangs in Tulsa, in a time that's a blurry mixture of the '50s and '80s; his greatest wish in life is to be respected and feared as much as his older brother, the Motorcycle Boy (Mickey Rourke), who vanished some months ago to pursue a life of reflection and peace, renouncing the life of gang-on-gang rumbles that Rusty James is to eager to keep alive. The Motorcycle Boy returns just in time to interfere in one such rumble, and the rest of the film exists as something like a discourse on themes of juvenile delinquency films, with Rusty James trying to figure up what's up with his brother, who exists somewhere between visionary madman and pacifist philosopher.

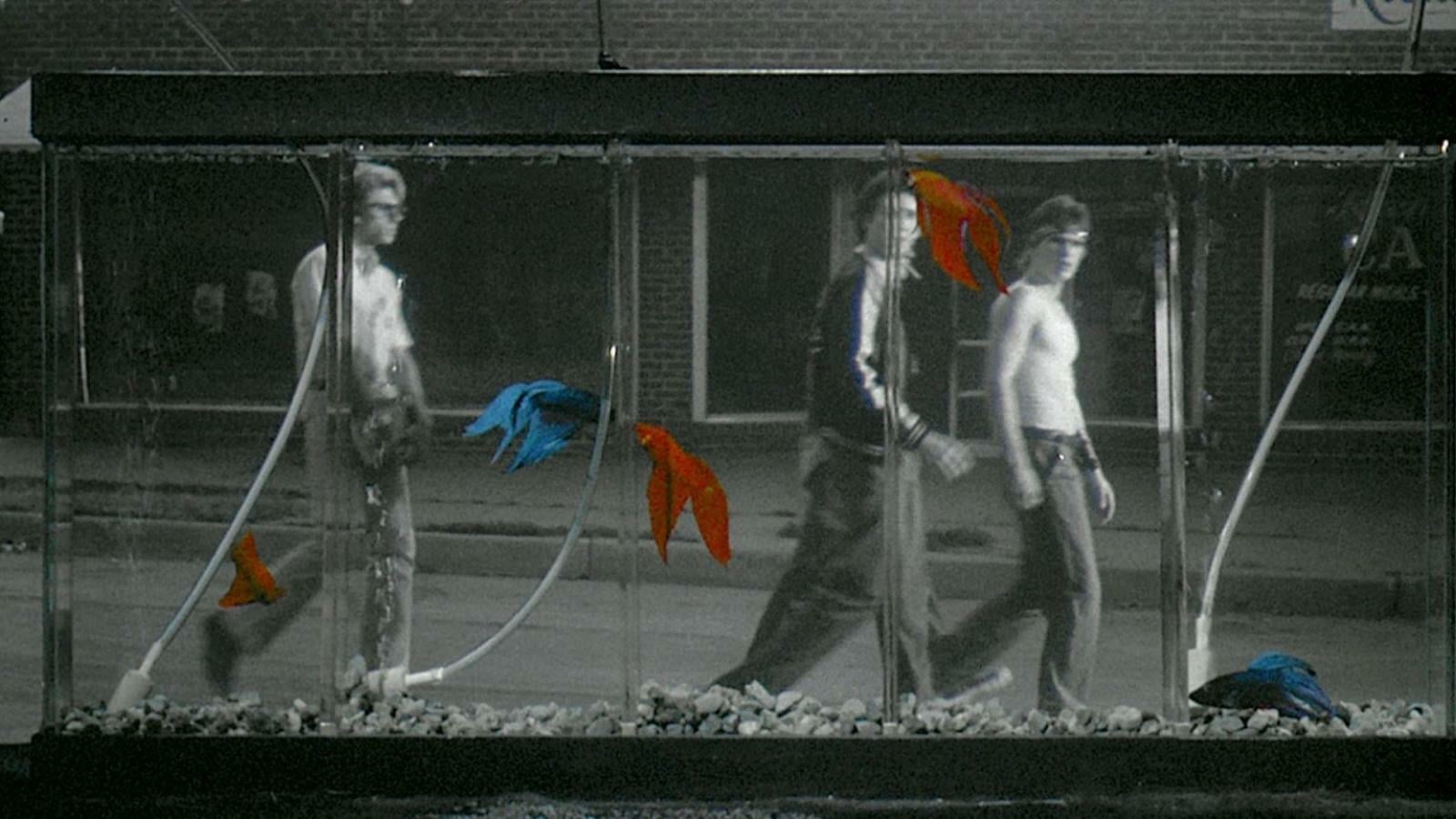

It's not really much of a story, so much as a collection of emotionally-charged incidents that combine to form a coming-of-age arc. This gauzy vagueness allows Coppola and his collaborators to create something that operates almost entirely at the level of mood, in a way that's remarkably difficult to pin down: it's sort like impressionism constructed with the tools of expressionism. Even the look of it is difficult to describe: it's high-contrast black and white that's dominated by shades of grey. That harsh greyness contributes to a sensation that the movie is coalescing out of mist, and the plot ends up feeling like it does much the same. There's an arch artificiality to everything we see, starting with the fact that Rusty James is called by exactly that two word phrase across the film, including in moments when it would make sense not to say his name at all, and this creates a highly formal feeling that's undermined by how ridiculous and slangy "Rusty James" sounds when spoken out loud; partially just by default, everybody who thus has to keep saying "Rusty James" feels like they're reciting an incantation rather than delivering dialogue. And this mood is already in place by the end of the film's very first line, delivered splendidly by Laurence Fishburne (whose arch, esoteric performance in The Matrix feels descended in a straight line from this one): "Biff Wilcox is looking for you, Rusty James. He's gonna kill you, Rusty James."

The artifice and the omnipresent shimmering greyness combine to create the feeling of a film that exists entirely within its own dream reality, constructed from isolated elements that are snatched from memories of JD movies, from German Expressionist cinema, from experimental films (Coppola borrowed the idea of time-lapse clouds from Koyaanisqatsi, a film whose trip into theaters earlier in 1983 was achieved largely through his sponsorship). It's nothing like anything else Coppola had directed to that point: while some of the patchy editing, based more upon Soviet Montage philosophies of combining images to create a third meaning than on Hollywood principles of building a cohesive space, recalls the highly subjective, impressionistic assembly of Apocalypse Now, in that film it emerged basically as an accident at the end of a torturous production, whereas here it feels motivated by the images themselves, bold iconic framings that seem designed to be appreciated as solitary frames. The result of all of this is a film that has genuinely mythic quality akin to the most artful of silent films, the ones drawing closest to a kind of narrative abstraction in which striking characters and bold, essentialised story elements are combined to create something like pure emotion.

The film can't ultimately keep this up: after the splendid experimental fury of those opening 20 minutes or so, it settles into a groove of being a very talky film about gang members, blessed by gorgeous cinematography and a well-chosen cast (including the likes of Diane Lane, Nicolas Cage, Diana Scarwid, Tom Waits, and a perhaps slightly too-obvious Dennis Hopper as the brothers' father) who figure out exactly what weirdness Coppola needs from them and don't resist it; or perhaps it would be better to say that they trust their director as he guides them towards these gaudy extremes of facial expression and vocal delivery. These things certainly keep it from being dull, and it helps that every now and then, the film returns to that elaborate expressionist feeling for a half scene or so. But it almost makes it easier to see why the film was so alarming to so many people in '83: if it was always operating at that heightened pitch, we'd know we had a pure art film on our hands and could deal with it appropriately, but given how some of it feels basically "normal", it's not hard to read those flourishes as the movie getting out of Coppola's control. It's definitely not that: everything feels too intuitively right (often not in a way that can be explicated) when the style bursts out for it to be an accident. Still, it's hard not to be disappointed when the impact of that astonishing opening starts to dissipate; there's a long stretch of the beginning of Rumble Fish that makes a real argument to being the best American filmmaking of the 1980s, and who wouldn't want an entire feature's worth of that?

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Francis Ford Coppola's popular reputation lies almost exclusively on the four films he made during the 1970s, every one an instantly-canonised masterpiece: 1972's The Godfather, 1974's The Conversation and The Godfather, Part II, 1979's Apocalypse Now. But for myself, I'm coming around to the idea that his subsequent run of movie in the 1980s is much more interesting. "Interesting" is not, of course, a synonym for "good". Still, there's something incredibly compelling about how Coppola dealt with the collapse of his production company and his directorial career following the disastrous failure of the brilliant, beautiful, insanely dysfunctional musical One from the Heart, from 1981. That film put him in director jail as hard as any multiple-Oscar winner ever has been so imprisoned, and for the next two decades, his career is a patchwork of very effortful attempts to be a Good Boy and make nice, commercially-sound genre pictures and weird indulgences where those attempts go spectacularly awry, resulting in something far more aggressively experimental than anything he was up to during his ostensible heyday.

We have now one of the weird indulgences in the form of Rumble Fish, the director's second feature released in 1983, and a film nearly as bold in its refusal to follow the rules as One from the Heart itself. The difference being that, at its strongest, One from the Heart is a glorious mess, while Rumble Fish spends its first act arguing for itself as the best film of Coppola's career. It doesn't stay at that level, but no matter how far it falls off, it's creative and challenging at a level that '80s American cinema barely knew how to work with. It's impossible not to compare it to his earlier 1983 film, The Outsiders: both are adaptations of novels by S.E. Hinton (she co-wrote the screenplay for this one with the director), both are set in Oklahoma and tell stories of teenage gang members with more of a focus on lyricism than crime. The biggest difference is that The Outsiders is basically a normal movie made with a fair level of craft, and for this it was one of the few films Coppola made in the '80s to turn a profit.

Rumble Fish, meanwhile, freaked out all of Hollywood, nearly got Coppola fired from The Cotton Club by producer Robert Evans, and only recouped a quarter of its production budget. I hate to say something as snotty as "this is because it was too good for audiences", but that's sort of exactly what's going on. That this and The Outsiders could come out right on top of each other, touching on the same milieu, and this is the one that tanked, does not make one feel especially good. Rumble Fish is an extraordinarily bold experiment in pretty much everything: the sleek high-contrast cinematography by Stephen H. Burum, the loose editing by Barry Malkin (it has a stunningly free feeling that I'd almost like to call "improvisational", as though the film was responding to stimuli along with the viewer rather than choosing stimuli for us), the heavily stylised performances, the unnaturalistic dialogue. Above all else, it's experimenting with the music by Stewart Copeland, drummer for The Police, who has accordingly provided the movie with an unusual percussive score: it's lilting and fairy-like at some points, action-heavy and driving at others, but in all instances, it's marked out by how goddamn exhausting it is to listen to: it's unrelenting, over-present in the sound mix, rhythmic at an uncomfortably fast past, and all in all does an ingenious job of getting the heart racing in a way that makes it very easy for all of the other stylisation to hit the viewer in a state of heightened sensitivity.

The plot hangs on a relationship between a teenager and his absent older brother, which already starts to get us to the reasons why Coppola treats the thing so strangely. Rusty James (Matt Dillon) is a member of one of two rival gangs in Tulsa, in a time that's a blurry mixture of the '50s and '80s; his greatest wish in life is to be respected and feared as much as his older brother, the Motorcycle Boy (Mickey Rourke), who vanished some months ago to pursue a life of reflection and peace, renouncing the life of gang-on-gang rumbles that Rusty James is to eager to keep alive. The Motorcycle Boy returns just in time to interfere in one such rumble, and the rest of the film exists as something like a discourse on themes of juvenile delinquency films, with Rusty James trying to figure up what's up with his brother, who exists somewhere between visionary madman and pacifist philosopher.

It's not really much of a story, so much as a collection of emotionally-charged incidents that combine to form a coming-of-age arc. This gauzy vagueness allows Coppola and his collaborators to create something that operates almost entirely at the level of mood, in a way that's remarkably difficult to pin down: it's sort like impressionism constructed with the tools of expressionism. Even the look of it is difficult to describe: it's high-contrast black and white that's dominated by shades of grey. That harsh greyness contributes to a sensation that the movie is coalescing out of mist, and the plot ends up feeling like it does much the same. There's an arch artificiality to everything we see, starting with the fact that Rusty James is called by exactly that two word phrase across the film, including in moments when it would make sense not to say his name at all, and this creates a highly formal feeling that's undermined by how ridiculous and slangy "Rusty James" sounds when spoken out loud; partially just by default, everybody who thus has to keep saying "Rusty James" feels like they're reciting an incantation rather than delivering dialogue. And this mood is already in place by the end of the film's very first line, delivered splendidly by Laurence Fishburne (whose arch, esoteric performance in The Matrix feels descended in a straight line from this one): "Biff Wilcox is looking for you, Rusty James. He's gonna kill you, Rusty James."

The artifice and the omnipresent shimmering greyness combine to create the feeling of a film that exists entirely within its own dream reality, constructed from isolated elements that are snatched from memories of JD movies, from German Expressionist cinema, from experimental films (Coppola borrowed the idea of time-lapse clouds from Koyaanisqatsi, a film whose trip into theaters earlier in 1983 was achieved largely through his sponsorship). It's nothing like anything else Coppola had directed to that point: while some of the patchy editing, based more upon Soviet Montage philosophies of combining images to create a third meaning than on Hollywood principles of building a cohesive space, recalls the highly subjective, impressionistic assembly of Apocalypse Now, in that film it emerged basically as an accident at the end of a torturous production, whereas here it feels motivated by the images themselves, bold iconic framings that seem designed to be appreciated as solitary frames. The result of all of this is a film that has genuinely mythic quality akin to the most artful of silent films, the ones drawing closest to a kind of narrative abstraction in which striking characters and bold, essentialised story elements are combined to create something like pure emotion.

The film can't ultimately keep this up: after the splendid experimental fury of those opening 20 minutes or so, it settles into a groove of being a very talky film about gang members, blessed by gorgeous cinematography and a well-chosen cast (including the likes of Diane Lane, Nicolas Cage, Diana Scarwid, Tom Waits, and a perhaps slightly too-obvious Dennis Hopper as the brothers' father) who figure out exactly what weirdness Coppola needs from them and don't resist it; or perhaps it would be better to say that they trust their director as he guides them towards these gaudy extremes of facial expression and vocal delivery. These things certainly keep it from being dull, and it helps that every now and then, the film returns to that elaborate expressionist feeling for a half scene or so. But it almost makes it easier to see why the film was so alarming to so many people in '83: if it was always operating at that heightened pitch, we'd know we had a pure art film on our hands and could deal with it appropriately, but given how some of it feels basically "normal", it's not hard to read those flourishes as the movie getting out of Coppola's control. It's definitely not that: everything feels too intuitively right (often not in a way that can be explicated) when the style bursts out for it to be an accident. Still, it's hard not to be disappointed when the impact of that astonishing opening starts to dissipate; there's a long stretch of the beginning of Rumble Fish that makes a real argument to being the best American filmmaking of the 1980s, and who wouldn't want an entire feature's worth of that?