Voyage to Italy

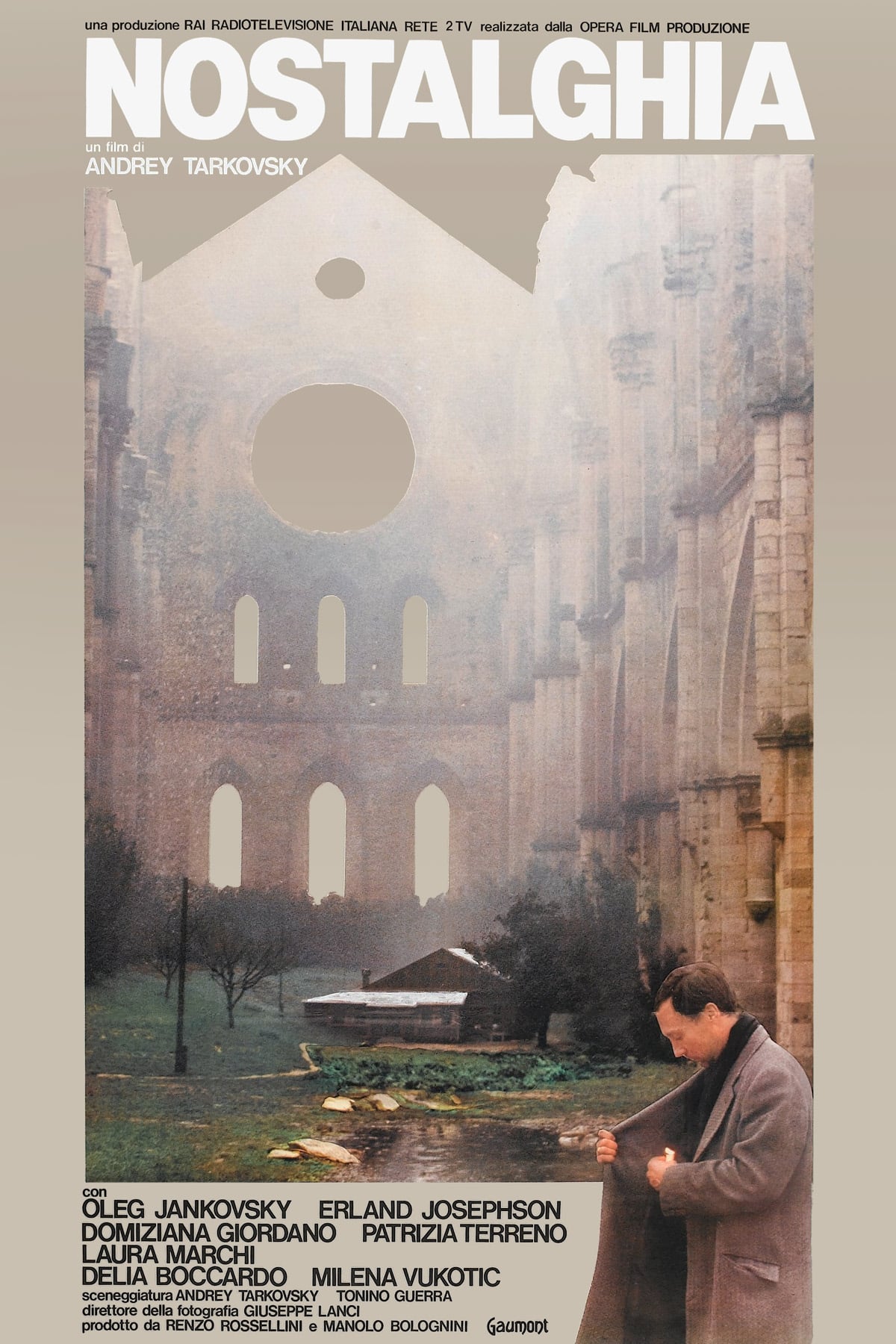

Between 1962 and 1986, Andrei Tarkovsky directed a mere seven feature films, and every single one of them was greeted as a major work. But 1983's Nostalghia, the sixth of those seven features and the firs made outside of the Soviet Union (it was shot in Italy, mostly in Tuscany), was regarded as being perhaps less major than the others right from the time of its premiere at the Cannes International Film Festival, and in all the years since, it's never quite shaken the reputation of being "the other one". This isn't to say that it's broadly considered a failure or any such thing: Tarkovsky won Best Director at Cannes (tying with Robert Bresson for L'argent), and the film also took the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury (the second of three times a Tarkovsky film would win that award) and the FIPRESCI Prize. It's just that something has to be the consensus pick for his lowest-ranked film, and this pretty clearly seems to be it.

I find this to be an extremely frustrating consensus. Nostalghia is in some ways a derivative movie that finds Tarkovsky repeating elements that have show up throughout his filmography (rain indoors, men with white patches of hair, long & slow tracking shots), feeling particularly like the midway point beween Mirror and Stalker, but it uses those familiar elements in new ways to new ends. In a sense, the fact that this echoes his earlier work so much is itself a critical part of the film's themes. With a name like Nostalghia, it's unsurprising that this is all about looking backwards; it is, among other things, about taking comfort in the old and familiar as a way of fending of fear and uncertainty about the new. The specific form it takes is of the story of a Russian man named Andrei who has left the Soviet Union to work in Italy, and it has customarily been the case to view this, therefore, as Tarkovsky's story about himself. It's easy to go too far with that, both because the specifics are different (Tarkovsky, for example, knew that he would never be able to return home) and because it frankly shouldn't matter when the film speaks for itself as eloquently as Nostalghia does; but there can be no doubt that Tarkovsky's own feelings of loss in being separated from his home country informed his choice of scenario, as well as how he approached the emotions stirred up by the scenario. And thus to we get to the first way in which this does represent something new and unique in the filmmaker's career: it, I think it's fair to say, his one nakedly emotional film. And I know he meant for Solaris to be nakedly emotional, and probably all of the others as well, in their way, but there's something appealingly simple about how that plays out in Nostalghia that isn't present in any of his other works. He even spoke about it as the film where he discovered just how much a film could be about giving concrete form to his own inner feelings and thoughts.

Mind you, "nakedly emotional" for this filmmaker still leaves a great deal of room for it to be pretty austere and intellectual. In fact, in addition to being the most humane of Tarkovsky films, I also find Nostalghia to be the most rigidly formalist: in none of his other films are we invited to notice such obvious visual patterns so often, mostly in the form of vertical compositional elements and right-to-left tracking shots (with occasional left-to-right shots, but somehow, these always seem to be "reversing" the camera, rather than serving as their own thing). It creates a structure for the film that its pointedly sparse narrative doesn't, and it plays into the fact that the protagonist, Andrei Gorchakov (Oleg Yankovsky, giving what I might tentatively be willing to call my favorite performance in a Tarkovsky film) is himself a poet, though that's not what brought him to Italy - he's there to do research on a Russian composer of the 18th Century who'd worked in the region. In fact, poetry is specifically not Gorchakov's purpose, for as he rather bluntly declares, "Poetry is untranslatable, like the whole of art" (he declares this in connection with an Italian-language collection of poems by Arseny Tarkovsky, the director's father). The ironies immediately stack up: first within the film: he's talking to his translator Eugenia (Domiziana Giordano), who speaks both Italian and Russian, as he himself does. And then around the film: Nostalghia is a film in Italian by a Russian filmmaker working with an Italian co-writer in the form of the great Tonino Guerra. And the outside of the film: I've reported this line to you in English, and I read it in English in little white words that were superimposed over the movie, absent Tarkovsky's artistic intentions.

Does Tarkovsky, or Nostalghia, actually believe that all art is untranslatable? It is, after nostalgia itself, the second most important concern of the movie. Eugenia starts to suggest music as an exception, which the film plays with (at two moments, the soundtrack uses selections from Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony - the one with voice singing in German), and the existence of the film seems to offer cinema as another possibility. Though less so than The Sacrifice, his next and final film, which would make this theme all but explicit, Nostalghia can be viewed as Tarkovsky's summary of a particular strain of European art cinema, converting into Russian idiom the work of some of the heaviest hitters in all of film history: Guerra's presence evokes the spectre of his frequent collaborator, Michelangelo Antonioni (and, retroactively, Theo Angelopoulos, with whom he'd start working the following year), who is also suggested by the film's wide shots of Italian spaces and its crushing sense of middle-class emptiness. The omnipresence of decaying stone buildings, and particularly the huge importance placed upon the visual of a large mineral pool brings in fellow Italian Federico Fellini, as well as the general sense of dreamy unreality sitting alongside the everyday. Giving a major role to Erland Josephson (who is, I believe, speaking his own lines in Italian) would obviously insist we think about Ingmar Bergman even if the heavily symbolic dream sequences and the floating, otherworldly quality to the overly intellectual conversations didn't do that as well.

The question then becomes, is Nostalghia attempting to "translate" these European art film traditions into Russian cinema? Or is the fact that the film itself is set in Italy and largely in Italian a concession that it's impossible to do so? Raising the question matters more than answering it, of course. Especially since ambiguity is the whole point: it leaves the film, like its protagonist, feeling like it exists in-between countries rather than spanning countries. And thus, the formalism: for form is the thing cinema has that exists outside of language and national styles. Mount the camera on a dolly and roll it to the left, and you always have a right-to-left tracking shot. It is, in a sense, what cinema has that's equivalent to the organising elements of poetry. Inasmuch as Nostalghia is about trying to make sense of a foreign environment that operates according to a literally different language, by using whatever structural elements exist outside of language - rhythm, imagery, stress. Film and poetry have different ways of creating rhythm and stress, and very different ways of presenting imagery, but I think it fits: the film is an attempt to cope with an unstable situation by trapping it within a poetic structure, and while "this film feels poetic" is always just about the least specific and most useless way you can describe a film, Nostalghia feels more poetic than most. The tracking shots "rhyme" with each other, giving the film a shape that is not, inherently, part of the nature of tracking shots; but it is a shape. It uses imagery of a German Shepherd that more or may not be part of Gorchakov's dream world as a repeated visual element - does it symbolise anything? Probably, but also provides a repeating anchor - there's a dog. We know that there's a dog. The presence of a dog unifies the film. I do not know if the dog needs meaning beyond being recognisable as the same dog.

The formal echoes do, of course, start to build their own meaning, and the film does an excellent job of training us how to watch it while we're watching it. The lateral camera movements across the film, over the course of its running time, start to build up a motif that what we're supposed to notice and think about is how small adjustments to a composition can completely change what we see in the image, especially with all the parallax created by those strong verticals throughout the movie. To be horribly literal about it, it's a film abut learning to see things from different angles, and how wildly our understanding of what's going on in an image can change our impression of its content. It's also about gradual changes: the camera moves a little bit, and then it moves a little more, and soon we're in a completely different situation, all without it ever having felt like something changed. Tarkovsky and cinematographer Giuseppe Lanci make a great deal of use out of these gradual shifts, in fact: one of the things Nostalghia is best at, besides moving the camera perpendicular to the direction it's facing, is to slowly change the quantity of light in a shot, all as a way of gently moving our attention around the frame without having to rely on big, muscular visual cues that would break the misty serenity of so many of the shots.

The height of the film's visual approach comes at the end, during a 9-minute tracking shot that follows Gorchakov as he very slowly walks to the left, while the camera is moving towards him (I suspect it's a zoom, but in the moment, I get so wrapped up in the scene that I forget to check) so slowly that it almost doesn't register until suddenly we realise that he's much bigger in the frame, continuing to move in until we just see his hands. It's the climax of the whole movie, in which the poet's desire to find some way of understanding the world is embodied in a spiritual gesture that he almost certainly knows is arbitrary and foolish - it's his attempt to fulfill the apocalyptic prophesies of Josephson's character, who seems dangerous and wrong on the one hand, but also like he's the only person who understands the feeling of heaviness and decay that the film's visuals so nimbly depict. And so Gorchakov's attempt to enact that man's will seems both frivolous, but also bizarrely hopeful, the one thing that he can actually do across the entire span of the movie. It's a thrilling scene, one of my favorite in any movie, and a big part of why is how it is the punchline to the entire film's training us to understand lateral tracking shots as the only thing that can give order to this failing world. It's followed, then, by a zoom-out on a final shot that's certainly my favorite closing image in all of Tarkovsky (it recalls, in form and content, the final shot of Solaris, but in the more personal register that this whole film has occupied), in part because the sudden interruption of a zoom feels so manifestly different than what we've watched up to this point.

It's a weakly hopeful ending to a film that has a very curious mood about it. It doesn't feel desparing the way that Stalker does, but it does have its own different kind of sadness. That's what nostalgia is, here: a feeling of sadness, of tangible separation from the familiar and the beloved. But it's sad in an unexpectedly warm way, for nostalgia is also a comfort. And there's a way in which Gorchakov's memories and dreams of the Soviet Union blend into Italy, partially through the unstable reality of a world filled with obvious poetic images and symbolism that find their way into the real world, partially because the "real" scenes keep fluctuating between muted colors and almost-all-the-way-desaturated colors, to evoke but never copy the black-and-white dream sequence. The present, in this way, can never entirely disentangle itself from the past, and that's ultimately what all of this is about: ancient buildings, old art, recent memories, all muddying themselves as something beautiful and dying, comforting and painful. It's a very human set of paradoxes and confusions for what I'd consider Tarkovsky's most emotionally accessible film, and the final no-two-ways-about-it masterpiece of his extraordinary career.

I find this to be an extremely frustrating consensus. Nostalghia is in some ways a derivative movie that finds Tarkovsky repeating elements that have show up throughout his filmography (rain indoors, men with white patches of hair, long & slow tracking shots), feeling particularly like the midway point beween Mirror and Stalker, but it uses those familiar elements in new ways to new ends. In a sense, the fact that this echoes his earlier work so much is itself a critical part of the film's themes. With a name like Nostalghia, it's unsurprising that this is all about looking backwards; it is, among other things, about taking comfort in the old and familiar as a way of fending of fear and uncertainty about the new. The specific form it takes is of the story of a Russian man named Andrei who has left the Soviet Union to work in Italy, and it has customarily been the case to view this, therefore, as Tarkovsky's story about himself. It's easy to go too far with that, both because the specifics are different (Tarkovsky, for example, knew that he would never be able to return home) and because it frankly shouldn't matter when the film speaks for itself as eloquently as Nostalghia does; but there can be no doubt that Tarkovsky's own feelings of loss in being separated from his home country informed his choice of scenario, as well as how he approached the emotions stirred up by the scenario. And thus to we get to the first way in which this does represent something new and unique in the filmmaker's career: it, I think it's fair to say, his one nakedly emotional film. And I know he meant for Solaris to be nakedly emotional, and probably all of the others as well, in their way, but there's something appealingly simple about how that plays out in Nostalghia that isn't present in any of his other works. He even spoke about it as the film where he discovered just how much a film could be about giving concrete form to his own inner feelings and thoughts.

Mind you, "nakedly emotional" for this filmmaker still leaves a great deal of room for it to be pretty austere and intellectual. In fact, in addition to being the most humane of Tarkovsky films, I also find Nostalghia to be the most rigidly formalist: in none of his other films are we invited to notice such obvious visual patterns so often, mostly in the form of vertical compositional elements and right-to-left tracking shots (with occasional left-to-right shots, but somehow, these always seem to be "reversing" the camera, rather than serving as their own thing). It creates a structure for the film that its pointedly sparse narrative doesn't, and it plays into the fact that the protagonist, Andrei Gorchakov (Oleg Yankovsky, giving what I might tentatively be willing to call my favorite performance in a Tarkovsky film) is himself a poet, though that's not what brought him to Italy - he's there to do research on a Russian composer of the 18th Century who'd worked in the region. In fact, poetry is specifically not Gorchakov's purpose, for as he rather bluntly declares, "Poetry is untranslatable, like the whole of art" (he declares this in connection with an Italian-language collection of poems by Arseny Tarkovsky, the director's father). The ironies immediately stack up: first within the film: he's talking to his translator Eugenia (Domiziana Giordano), who speaks both Italian and Russian, as he himself does. And then around the film: Nostalghia is a film in Italian by a Russian filmmaker working with an Italian co-writer in the form of the great Tonino Guerra. And the outside of the film: I've reported this line to you in English, and I read it in English in little white words that were superimposed over the movie, absent Tarkovsky's artistic intentions.

Does Tarkovsky, or Nostalghia, actually believe that all art is untranslatable? It is, after nostalgia itself, the second most important concern of the movie. Eugenia starts to suggest music as an exception, which the film plays with (at two moments, the soundtrack uses selections from Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony - the one with voice singing in German), and the existence of the film seems to offer cinema as another possibility. Though less so than The Sacrifice, his next and final film, which would make this theme all but explicit, Nostalghia can be viewed as Tarkovsky's summary of a particular strain of European art cinema, converting into Russian idiom the work of some of the heaviest hitters in all of film history: Guerra's presence evokes the spectre of his frequent collaborator, Michelangelo Antonioni (and, retroactively, Theo Angelopoulos, with whom he'd start working the following year), who is also suggested by the film's wide shots of Italian spaces and its crushing sense of middle-class emptiness. The omnipresence of decaying stone buildings, and particularly the huge importance placed upon the visual of a large mineral pool brings in fellow Italian Federico Fellini, as well as the general sense of dreamy unreality sitting alongside the everyday. Giving a major role to Erland Josephson (who is, I believe, speaking his own lines in Italian) would obviously insist we think about Ingmar Bergman even if the heavily symbolic dream sequences and the floating, otherworldly quality to the overly intellectual conversations didn't do that as well.

The question then becomes, is Nostalghia attempting to "translate" these European art film traditions into Russian cinema? Or is the fact that the film itself is set in Italy and largely in Italian a concession that it's impossible to do so? Raising the question matters more than answering it, of course. Especially since ambiguity is the whole point: it leaves the film, like its protagonist, feeling like it exists in-between countries rather than spanning countries. And thus, the formalism: for form is the thing cinema has that exists outside of language and national styles. Mount the camera on a dolly and roll it to the left, and you always have a right-to-left tracking shot. It is, in a sense, what cinema has that's equivalent to the organising elements of poetry. Inasmuch as Nostalghia is about trying to make sense of a foreign environment that operates according to a literally different language, by using whatever structural elements exist outside of language - rhythm, imagery, stress. Film and poetry have different ways of creating rhythm and stress, and very different ways of presenting imagery, but I think it fits: the film is an attempt to cope with an unstable situation by trapping it within a poetic structure, and while "this film feels poetic" is always just about the least specific and most useless way you can describe a film, Nostalghia feels more poetic than most. The tracking shots "rhyme" with each other, giving the film a shape that is not, inherently, part of the nature of tracking shots; but it is a shape. It uses imagery of a German Shepherd that more or may not be part of Gorchakov's dream world as a repeated visual element - does it symbolise anything? Probably, but also provides a repeating anchor - there's a dog. We know that there's a dog. The presence of a dog unifies the film. I do not know if the dog needs meaning beyond being recognisable as the same dog.

The formal echoes do, of course, start to build their own meaning, and the film does an excellent job of training us how to watch it while we're watching it. The lateral camera movements across the film, over the course of its running time, start to build up a motif that what we're supposed to notice and think about is how small adjustments to a composition can completely change what we see in the image, especially with all the parallax created by those strong verticals throughout the movie. To be horribly literal about it, it's a film abut learning to see things from different angles, and how wildly our understanding of what's going on in an image can change our impression of its content. It's also about gradual changes: the camera moves a little bit, and then it moves a little more, and soon we're in a completely different situation, all without it ever having felt like something changed. Tarkovsky and cinematographer Giuseppe Lanci make a great deal of use out of these gradual shifts, in fact: one of the things Nostalghia is best at, besides moving the camera perpendicular to the direction it's facing, is to slowly change the quantity of light in a shot, all as a way of gently moving our attention around the frame without having to rely on big, muscular visual cues that would break the misty serenity of so many of the shots.

The height of the film's visual approach comes at the end, during a 9-minute tracking shot that follows Gorchakov as he very slowly walks to the left, while the camera is moving towards him (I suspect it's a zoom, but in the moment, I get so wrapped up in the scene that I forget to check) so slowly that it almost doesn't register until suddenly we realise that he's much bigger in the frame, continuing to move in until we just see his hands. It's the climax of the whole movie, in which the poet's desire to find some way of understanding the world is embodied in a spiritual gesture that he almost certainly knows is arbitrary and foolish - it's his attempt to fulfill the apocalyptic prophesies of Josephson's character, who seems dangerous and wrong on the one hand, but also like he's the only person who understands the feeling of heaviness and decay that the film's visuals so nimbly depict. And so Gorchakov's attempt to enact that man's will seems both frivolous, but also bizarrely hopeful, the one thing that he can actually do across the entire span of the movie. It's a thrilling scene, one of my favorite in any movie, and a big part of why is how it is the punchline to the entire film's training us to understand lateral tracking shots as the only thing that can give order to this failing world. It's followed, then, by a zoom-out on a final shot that's certainly my favorite closing image in all of Tarkovsky (it recalls, in form and content, the final shot of Solaris, but in the more personal register that this whole film has occupied), in part because the sudden interruption of a zoom feels so manifestly different than what we've watched up to this point.

It's a weakly hopeful ending to a film that has a very curious mood about it. It doesn't feel desparing the way that Stalker does, but it does have its own different kind of sadness. That's what nostalgia is, here: a feeling of sadness, of tangible separation from the familiar and the beloved. But it's sad in an unexpectedly warm way, for nostalgia is also a comfort. And there's a way in which Gorchakov's memories and dreams of the Soviet Union blend into Italy, partially through the unstable reality of a world filled with obvious poetic images and symbolism that find their way into the real world, partially because the "real" scenes keep fluctuating between muted colors and almost-all-the-way-desaturated colors, to evoke but never copy the black-and-white dream sequence. The present, in this way, can never entirely disentangle itself from the past, and that's ultimately what all of this is about: ancient buildings, old art, recent memories, all muddying themselves as something beautiful and dying, comforting and painful. It's a very human set of paradoxes and confusions for what I'd consider Tarkovsky's most emotionally accessible film, and the final no-two-ways-about-it masterpiece of his extraordinary career.