We gonna make you laugh, we gonna make you cry, but most of all, we gonna NAIL YOUR ASS!

The first question about 2003's Intolerable Cruelty to tackle is, why in God's name did the Coen brothers make it? Their tenth feature as co-directors (and the last one which Joel took sole official credit for directing and Ethan for producing - that is, Ethan was credited along with Brian Grazer, but I hope you know what I mean) is also, by any measure I could imagine using, the one that feels the least passionate, with the least energy being poured into making it something weird and special. It's also, by a pretty substantial margin, the most expensive film they've made,* with a $60 million price tag, and while not every great indie filmmaker has suffered from "selling out" and making a studio production, that's definitely a charge that I think you could pretty easily make stick in this case. It feels like a work-for-hire job, muted in its energy and with only a handful of gags strewn across the 100-minute running time that even glance in the direction of the sharp meanness and erudite cynicism and irony of the brothers's best work. And for that matter, even their middling work.

So back we go: why did they make it? It goes a bit like this: John Romano had come up with an idea for a story, and Robert Ramsey & Matthew Stone turned it into a screenplay. The film passed into the hands of Ron Howard, which is how Grazer got involved, and later on Jonathan Demme was attached; it would have been an unusually biting Howard film and a pretty great fit for Demme, which is the clearest sign I can think of why it's not a great fit for the Coens; but at some point in the '90s, they were hired to do a re-write of the script. Meanwhile, after The Man Who Wasn't There, they got to work on developing an adaptation of the novel To the White Sea, something that had been on their radar for at least a couple of years at that point. Eventually, that project collapsed, and so, with no job to do, and their much-admired script having sat around gathering dust for years, they teamed up with Grazer to finally bring Intolerable Cruelty into the world.

So there it is: a project that existed mostly to keep the filmmakers busy. It definitely feels like that's about the amount of enthusiasm they put into it, to. It's not that this is bad, and by the standards of studio-made romantic comedies in the first half of the 2000s, it is in fact considerably better than average. But it is extremely anonymous, and frequently not very funny, and without any sort of edge or cartoon energy that would keep it afloat in those moments when it's not very funny.

The idea is a modern take on the divorce comedies of the 1930s. Miles Massey (George Clooney), is a world-renowned divorce lawyer, creator of the impenetrable Massey Pre-nup, a legal document so extraordinary that it's the subject of an entire course at Harvard Law. We first see him... well wait, actually we first see Donovan Donaly (Geoffrey Rush), a TV producer who arrives whom to see his wife Bonnie (Stacey Travis) trying to hide the pool boy, Ollie Olerud (Jack Kyle), with whom she's been having an affair, despite the fact that the Donalys don't even have a pool. It's a clear-cut case of infidelity, and Donovan does everything he needs to in order to make sure Bonnie won't get a penny, but after this very long pre-title scene (and a very wonderful credits sequence, with Victorian-style romantic illustrations crudely animated to enact the process of falling in love and then divorcing), we find that Bonnie has gone to Miles, who relishes the chance to see if he can win some money for her, despite how self-evidently she doesn't deserve any. And indeed, he does this.

Everything I've said so far doesn't matter. Donovan Donaly, despite being both the first and the last character we see in the movie, is barely even a tertiary character; he exists so Bonnie can exist, and Bonnie exists so we can see the way Miles's scheming legalistic mind works. And that's useful to establish before we get to the actual plot, but there's still the matter of that very long opening sequence, which dawdles so very hard: dawdles on how Donovan can't sing along to Simon & Garfunkel's "The Boxer" (setting up a film-long motif of Simon & Garfunkel that ends up contributing very little other than a sense of what soundtracks all Coen films would have if they all cost $60 million), dawdles on his taunting of Bonnie and Ollie. Everything feels like it's moving at half-speed, with Rush's performance strolling through dialogue that might have worked better if it were spat out like a machine gun, but even when, the question would persist: why is this scene here? The Coens are not averse to making languid, shaggy movies, with lots of random asides and odds & ends, but there's a sense of purpose to the shagginess in something like Raising Arizona or The Big Lebowski, the feel thing that a vibe is being created. Intolerable Cruelty has no vibe, and if it did, it wouldn't be a shaggy one: this is a comedy based in the precision of two tactical geniuses trying to outflank the other, modeled after a breed of comedies that are noteworthy in large part for how airtight and well-designed they are. For Intolerable Cruelty to kick off with such a yawning, unhurried, aimless opening could be seen as part of the Coens' overall love of deconstructing genres (though their pure comedies tend to be much less deconstructive than their other movies), but it really reads as a "fuck this, why are we even making this?" gesture. And a sense of random tone-shifting will never leave Intolerable Cruelty from this point onward.

Anyway, once we learn that Miles is a genius, we can get into the real action, which is that the philandering Rex Rexroth (Edward Herrmann, whose only appearance in a Coen film should have been in a better one than this) has recently been caught by his wife Marilyn (Catherine Zeta-Jones), an obvious gold-digger - but also an extremely good gold-digger, who knows how to hide her tracks. Still, Miles is a genius, and he's able to flatten her in court, while also falling head-over-heels in lust with her. And from this moment on, their paths will keep crossing, with it clear enough that she has revenge on her mind, though a bit of mystery how that revenge is going to manifest. And, of course, since George Clooney and Catherine Zeta-Jones are both breathtakingly gorgeous movie stars, we can take it on faith that at some point, her desire to destroy him and his deeply cynical views on romantic relationships are both going to run into the wall of True Love.

Even more than its shagginess, the biggest problem by far with Intolerable Cruelty is that central relationship. Are the two actors hot together, and do I buy their chemistry? Absolutely yes. But I super don't care. The Coens can and have portrayed completely happy, healthy romances in their films - Marge and Norm Gunderson in Fargo is the obvious case, but the loopy idiots in love H.I. and Ed in Raising Arizona are the better comparison, given that Marge and Norm are the counterbalance to all the human misery in that film, whereas H.I. and Ed are the subjects of their story. I cannot quantify the difference between those two and Miles and Marilyn, except to say that the filmmakers don't feel like they give a shit. In particular, they obviously have no real interest in Marilyn, or in helping Zeta-Jones do anything with the role that isn't clearly present on the page - offhand, I'm pretty sure she's giving the most flavorless performance of a lead role in any film the Coens have ever made. I certainly wouldn't use the same word, "flavorless" to describe what Clooney is up to, but the end result isn't much better. It seems to me that the actor wants to do something much bigger and goofier than the film has room for, another fast-talking flimflam man on the model of his performance in O Brother, Where Art Thou? with a JD. He's bugging out his eyes and pulling faces as much as the film allows, which turns out not to be very much - Intolerable Cruelty's need to function as a movie star romcom means that it wants Dashing Charmer Clooney much more than Flailing Imbecile Clooney, and so his performance keeps bashing against the ceiling of the script. It ends up feeling inconsistent and tonally incoherent, a bad performance emerging from the ashes of a potentially great one.

The emptiness of the central relationship, and the flatlining of Miles's personality, both mean that the film basically cannot function on the level it overtly wants to. The plot itself ends up feeling lifeless and perfunctory; Miles's character arc is completely hollow and emotionally inert, with his big change of heart speech not even treated with enough caustic cynicism to work as generic snotty ironic comedy.

That being said, the film isn't a total wash, and in fact I enjoyed it more now than I did in October 2003, when it felt like part of the Coens' headlong tumble from the greatness of their '90s masterpieces into increasingly empty genre walkthroughs that haven't figured out a reason for their own existence. The knowledge that they'd reverse this trend after another few years helps; so does the knowledge that their very next film, The Ladykillers, is even worse, which is enough to make this one feel slightly better in comparison. And anyway, there's goodness to be found within the film. The center of the film might be fairly dull, but the bright colors the filmmakers are using around the edges make up for a lot of that. It's not new for the Coens to be fascinated by their supporting casts and character actors, and Intolerable Cruelty has a great one in the form of Richard Jenkins, a natural fit for their style who gives this film, easily, its best performance. He plays Miles's rival lawyer, Freddy Bender, and he only shows up in four scenes, two of them so small as to barely count. But in the first two, he points the way into a much better film on the theme of cynical lawyers than the one we actually got: when he and Clooney sling legalese at each other, boosting the speed of the dialogue, it becomes, ever so briefly, a top-notch banter-based comedy. And his hapless attempts to raise objections during a courtroom scene manages to redeem a sequence that was going pretty far off-track with an awful parody of a European fop played with nonexistent nuance by Jonathan Hadary.

The film lives entirely in grace notes like these. The senior partner of Miles's firm (Tom Aldredge) is portrayed as something like a German Expressionist gargoyle; a waitress (Mary Pat Gleason) at a crummy diner brings a note of sardonic irritation that makes her feel, for just a couple of lines (including the film's only use of the word "fuck"; the screenplay had to be bleached clean to guarantee a PG-13 rating), like the one true Coen character in the movie; an asthmatic assassin (Irwin Keyes) who gets the film's funniest sight gag, which is also its only piece of actual dark humor. Not everything works - Cedric the Entertainer's role as a crude private eye demonstrates the firm limits of the Coens' ability to write dialogue for Black characters, and Rush is simply droning and unfunny - but enough works, marginally, for the film to end up being funny enough that it's not a complete waste of time.

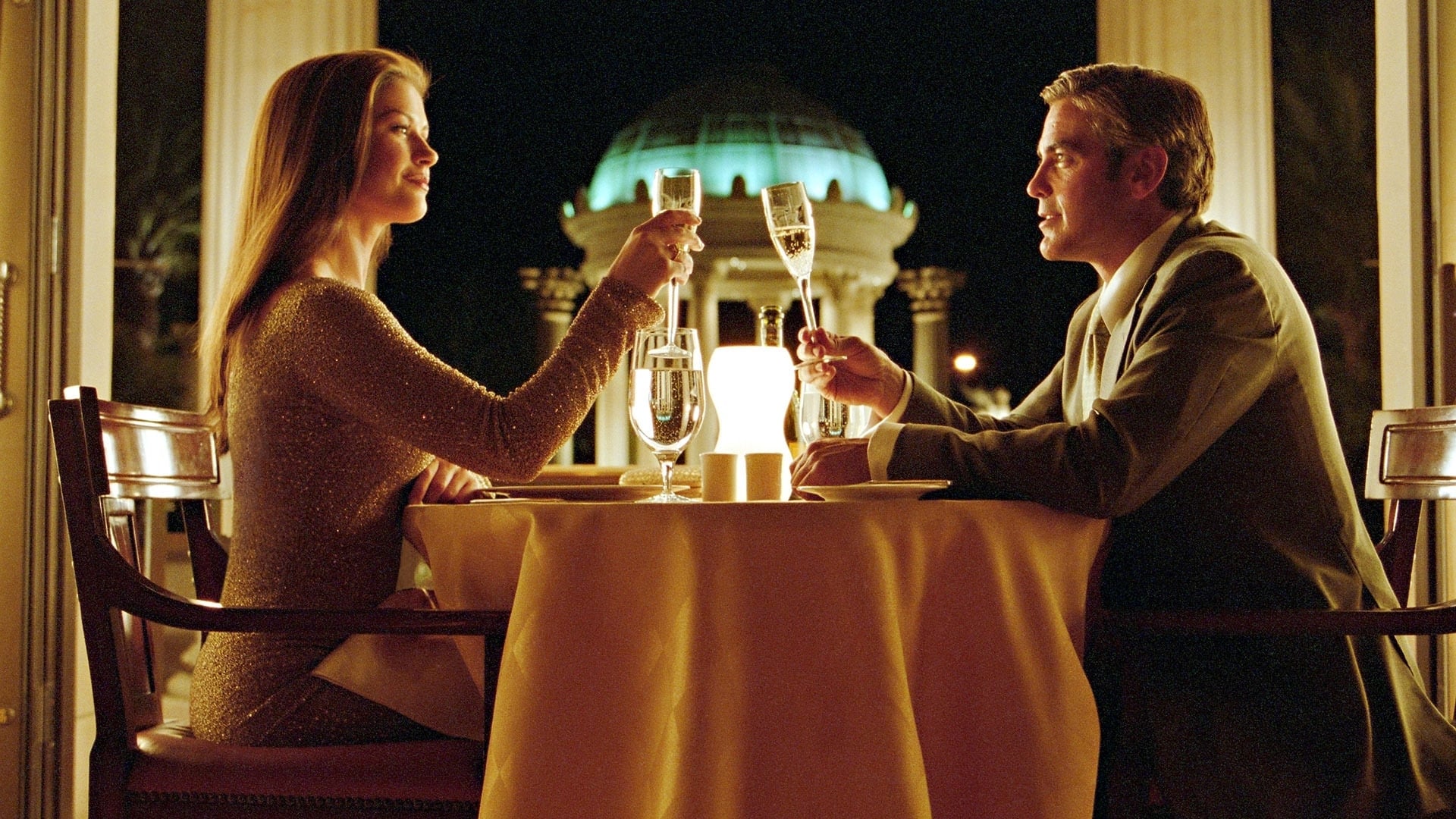

The most consistently funny element, however, is probably the score, composed by Coen mainstay Carter Burwell. He's always a benefit to the brothers' films, but this time around is probably the only time he's actually carrying the film on his back: the music has a light adventure-comedy mood that plays sarcastically with the images often enough to give the film some measure of comic personality even when it's not doing much else to be funny. As for the rest of the Coens' usual collaborators, they're doing fine, if mostly unexceptional work: the fact that this isn't a period film (the first Coen movie since Raising Arizona set during the same year it was released), and that the whole cast is well-off Angelinos, means that Mary Zophres doesn't have much to do in the way of imaginative costuming. Cinematographer Roger Deakins has shot the film with his usual gorgeous talent - the film is drenched in rich golden hues that make everything seem elegant and rich, but in a somewhat hostile, underlit way. And the shifts in contrast, color, and graininess to vividly contrast different kinds of spaces works extraordinarily well. But it's almost too much; the film wants to be a light, fun comedy, and it's been shot to feel very close and heavy, too polished and moody for the comedy to escape from all of the visual texturing. Sound designer Skip Lievsay has fun working in the film's musical elements, though without the verve and vitality of O Brother.

Let us be clear: if this works, it is by only the thinnest margin. There are a good number of parts I like, and at least three I love (the two big Richard Jenkins scenes, and the aforementioned gag involving the assassin), but there are far more where I feel completely checked out of the movie and its characters. This isn't, sadly, the worst Coen brothers movie, but I have to imagine that it's the most boring, and while I'm not depressed by it like I was in 2003 (for I now know that this decline has a bottom, and will soon enough reverse) I absolutely cannot begin to see the secret masterpiece that some revisionist Coen fans have tried to excavate from it in recent years. It's a bland studio comedy with some genuinely terrific bits - let us not try to make it more than that, and for my own part, I don't know that I'll be chancing a third encounter with the movie anytime soon.

*Give or take the fact that Netflix has never officially announced how much The Ballad of Buster Scruggs cost.

So back we go: why did they make it? It goes a bit like this: John Romano had come up with an idea for a story, and Robert Ramsey & Matthew Stone turned it into a screenplay. The film passed into the hands of Ron Howard, which is how Grazer got involved, and later on Jonathan Demme was attached; it would have been an unusually biting Howard film and a pretty great fit for Demme, which is the clearest sign I can think of why it's not a great fit for the Coens; but at some point in the '90s, they were hired to do a re-write of the script. Meanwhile, after The Man Who Wasn't There, they got to work on developing an adaptation of the novel To the White Sea, something that had been on their radar for at least a couple of years at that point. Eventually, that project collapsed, and so, with no job to do, and their much-admired script having sat around gathering dust for years, they teamed up with Grazer to finally bring Intolerable Cruelty into the world.

So there it is: a project that existed mostly to keep the filmmakers busy. It definitely feels like that's about the amount of enthusiasm they put into it, to. It's not that this is bad, and by the standards of studio-made romantic comedies in the first half of the 2000s, it is in fact considerably better than average. But it is extremely anonymous, and frequently not very funny, and without any sort of edge or cartoon energy that would keep it afloat in those moments when it's not very funny.

The idea is a modern take on the divorce comedies of the 1930s. Miles Massey (George Clooney), is a world-renowned divorce lawyer, creator of the impenetrable Massey Pre-nup, a legal document so extraordinary that it's the subject of an entire course at Harvard Law. We first see him... well wait, actually we first see Donovan Donaly (Geoffrey Rush), a TV producer who arrives whom to see his wife Bonnie (Stacey Travis) trying to hide the pool boy, Ollie Olerud (Jack Kyle), with whom she's been having an affair, despite the fact that the Donalys don't even have a pool. It's a clear-cut case of infidelity, and Donovan does everything he needs to in order to make sure Bonnie won't get a penny, but after this very long pre-title scene (and a very wonderful credits sequence, with Victorian-style romantic illustrations crudely animated to enact the process of falling in love and then divorcing), we find that Bonnie has gone to Miles, who relishes the chance to see if he can win some money for her, despite how self-evidently she doesn't deserve any. And indeed, he does this.

Everything I've said so far doesn't matter. Donovan Donaly, despite being both the first and the last character we see in the movie, is barely even a tertiary character; he exists so Bonnie can exist, and Bonnie exists so we can see the way Miles's scheming legalistic mind works. And that's useful to establish before we get to the actual plot, but there's still the matter of that very long opening sequence, which dawdles so very hard: dawdles on how Donovan can't sing along to Simon & Garfunkel's "The Boxer" (setting up a film-long motif of Simon & Garfunkel that ends up contributing very little other than a sense of what soundtracks all Coen films would have if they all cost $60 million), dawdles on his taunting of Bonnie and Ollie. Everything feels like it's moving at half-speed, with Rush's performance strolling through dialogue that might have worked better if it were spat out like a machine gun, but even when, the question would persist: why is this scene here? The Coens are not averse to making languid, shaggy movies, with lots of random asides and odds & ends, but there's a sense of purpose to the shagginess in something like Raising Arizona or The Big Lebowski, the feel thing that a vibe is being created. Intolerable Cruelty has no vibe, and if it did, it wouldn't be a shaggy one: this is a comedy based in the precision of two tactical geniuses trying to outflank the other, modeled after a breed of comedies that are noteworthy in large part for how airtight and well-designed they are. For Intolerable Cruelty to kick off with such a yawning, unhurried, aimless opening could be seen as part of the Coens' overall love of deconstructing genres (though their pure comedies tend to be much less deconstructive than their other movies), but it really reads as a "fuck this, why are we even making this?" gesture. And a sense of random tone-shifting will never leave Intolerable Cruelty from this point onward.

Anyway, once we learn that Miles is a genius, we can get into the real action, which is that the philandering Rex Rexroth (Edward Herrmann, whose only appearance in a Coen film should have been in a better one than this) has recently been caught by his wife Marilyn (Catherine Zeta-Jones), an obvious gold-digger - but also an extremely good gold-digger, who knows how to hide her tracks. Still, Miles is a genius, and he's able to flatten her in court, while also falling head-over-heels in lust with her. And from this moment on, their paths will keep crossing, with it clear enough that she has revenge on her mind, though a bit of mystery how that revenge is going to manifest. And, of course, since George Clooney and Catherine Zeta-Jones are both breathtakingly gorgeous movie stars, we can take it on faith that at some point, her desire to destroy him and his deeply cynical views on romantic relationships are both going to run into the wall of True Love.

Even more than its shagginess, the biggest problem by far with Intolerable Cruelty is that central relationship. Are the two actors hot together, and do I buy their chemistry? Absolutely yes. But I super don't care. The Coens can and have portrayed completely happy, healthy romances in their films - Marge and Norm Gunderson in Fargo is the obvious case, but the loopy idiots in love H.I. and Ed in Raising Arizona are the better comparison, given that Marge and Norm are the counterbalance to all the human misery in that film, whereas H.I. and Ed are the subjects of their story. I cannot quantify the difference between those two and Miles and Marilyn, except to say that the filmmakers don't feel like they give a shit. In particular, they obviously have no real interest in Marilyn, or in helping Zeta-Jones do anything with the role that isn't clearly present on the page - offhand, I'm pretty sure she's giving the most flavorless performance of a lead role in any film the Coens have ever made. I certainly wouldn't use the same word, "flavorless" to describe what Clooney is up to, but the end result isn't much better. It seems to me that the actor wants to do something much bigger and goofier than the film has room for, another fast-talking flimflam man on the model of his performance in O Brother, Where Art Thou? with a JD. He's bugging out his eyes and pulling faces as much as the film allows, which turns out not to be very much - Intolerable Cruelty's need to function as a movie star romcom means that it wants Dashing Charmer Clooney much more than Flailing Imbecile Clooney, and so his performance keeps bashing against the ceiling of the script. It ends up feeling inconsistent and tonally incoherent, a bad performance emerging from the ashes of a potentially great one.

The emptiness of the central relationship, and the flatlining of Miles's personality, both mean that the film basically cannot function on the level it overtly wants to. The plot itself ends up feeling lifeless and perfunctory; Miles's character arc is completely hollow and emotionally inert, with his big change of heart speech not even treated with enough caustic cynicism to work as generic snotty ironic comedy.

That being said, the film isn't a total wash, and in fact I enjoyed it more now than I did in October 2003, when it felt like part of the Coens' headlong tumble from the greatness of their '90s masterpieces into increasingly empty genre walkthroughs that haven't figured out a reason for their own existence. The knowledge that they'd reverse this trend after another few years helps; so does the knowledge that their very next film, The Ladykillers, is even worse, which is enough to make this one feel slightly better in comparison. And anyway, there's goodness to be found within the film. The center of the film might be fairly dull, but the bright colors the filmmakers are using around the edges make up for a lot of that. It's not new for the Coens to be fascinated by their supporting casts and character actors, and Intolerable Cruelty has a great one in the form of Richard Jenkins, a natural fit for their style who gives this film, easily, its best performance. He plays Miles's rival lawyer, Freddy Bender, and he only shows up in four scenes, two of them so small as to barely count. But in the first two, he points the way into a much better film on the theme of cynical lawyers than the one we actually got: when he and Clooney sling legalese at each other, boosting the speed of the dialogue, it becomes, ever so briefly, a top-notch banter-based comedy. And his hapless attempts to raise objections during a courtroom scene manages to redeem a sequence that was going pretty far off-track with an awful parody of a European fop played with nonexistent nuance by Jonathan Hadary.

The film lives entirely in grace notes like these. The senior partner of Miles's firm (Tom Aldredge) is portrayed as something like a German Expressionist gargoyle; a waitress (Mary Pat Gleason) at a crummy diner brings a note of sardonic irritation that makes her feel, for just a couple of lines (including the film's only use of the word "fuck"; the screenplay had to be bleached clean to guarantee a PG-13 rating), like the one true Coen character in the movie; an asthmatic assassin (Irwin Keyes) who gets the film's funniest sight gag, which is also its only piece of actual dark humor. Not everything works - Cedric the Entertainer's role as a crude private eye demonstrates the firm limits of the Coens' ability to write dialogue for Black characters, and Rush is simply droning and unfunny - but enough works, marginally, for the film to end up being funny enough that it's not a complete waste of time.

The most consistently funny element, however, is probably the score, composed by Coen mainstay Carter Burwell. He's always a benefit to the brothers' films, but this time around is probably the only time he's actually carrying the film on his back: the music has a light adventure-comedy mood that plays sarcastically with the images often enough to give the film some measure of comic personality even when it's not doing much else to be funny. As for the rest of the Coens' usual collaborators, they're doing fine, if mostly unexceptional work: the fact that this isn't a period film (the first Coen movie since Raising Arizona set during the same year it was released), and that the whole cast is well-off Angelinos, means that Mary Zophres doesn't have much to do in the way of imaginative costuming. Cinematographer Roger Deakins has shot the film with his usual gorgeous talent - the film is drenched in rich golden hues that make everything seem elegant and rich, but in a somewhat hostile, underlit way. And the shifts in contrast, color, and graininess to vividly contrast different kinds of spaces works extraordinarily well. But it's almost too much; the film wants to be a light, fun comedy, and it's been shot to feel very close and heavy, too polished and moody for the comedy to escape from all of the visual texturing. Sound designer Skip Lievsay has fun working in the film's musical elements, though without the verve and vitality of O Brother.

Let us be clear: if this works, it is by only the thinnest margin. There are a good number of parts I like, and at least three I love (the two big Richard Jenkins scenes, and the aforementioned gag involving the assassin), but there are far more where I feel completely checked out of the movie and its characters. This isn't, sadly, the worst Coen brothers movie, but I have to imagine that it's the most boring, and while I'm not depressed by it like I was in 2003 (for I now know that this decline has a bottom, and will soon enough reverse) I absolutely cannot begin to see the secret masterpiece that some revisionist Coen fans have tried to excavate from it in recent years. It's a bland studio comedy with some genuinely terrific bits - let us not try to make it more than that, and for my own part, I don't know that I'll be chancing a third encounter with the movie anytime soon.

*Give or take the fact that Netflix has never officially announced how much The Ballad of Buster Scruggs cost.

Categories: comedies, courtroom dramas, romcoms, the coen brothers