What I know about is Texas, an' down here, you're on your own

It's right around the 14-minute mark in 1984's Blood Simple that Joel & Ethan Coen first become "the Coen Brothers". It's a short, single-take scene set in bar, and the scene starts all the way at the far end of the bar from the characters we actually care about. So the camera tracks forward, right above the level of the bar, and at a certain point, it encounters a man passed out from drinking, slumped right around the path of the camera's movement. And so it simply rises up to move over his head, before moving back down to its original height as it continues to move forward. That moment, a completely unnecessary and even distracting bit of absurd meta-cinematic humor, executed with a perfectly straight face and almost stately elegance, isn't one of the big things that people talk about when they talk about the film, of course. It's a throwaway gag during a scene that only barely pushes the plot forward. But it is also the single beat, in all of the film's running time (99 minutes in the original theatrical cut, 95 in the tightened-up 1998 director's cut that is at this point basically the only way to see the film; it changes very little, but that still rankles my film historian's heart) that most directly points to the filmmakers that the Coens would become. It's a shaggy add-on that has nothing to do with what the film is up to, but it introduces some playful irony and a whole lot of color and personality, and it makes the movie feel more unpredictable and living and organic than all the plot twists in all the world.

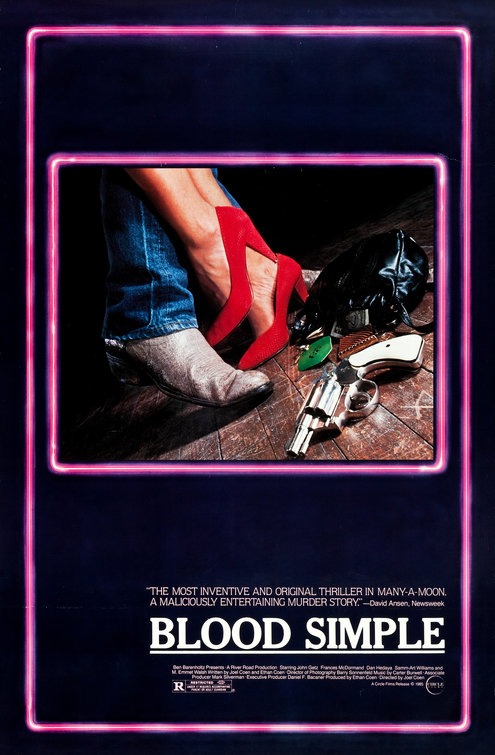

But there I go, doing the thing I promised myself not to do, which is treating Blood Simple like it's only good precisely insofar as it anticipates the Coen filmography to come. Far more fair, and far more honest, to look at it in its proper context of 1984, when American independent filmmaking was just starting to wake up: the Sundance Institute took over the US Film and Video Festival and prepared to rebrand it as a major focal point for independent cinema (Blood Simple would win the Grand Jury Prize at the 1985 festival, in a vanishingly rare example of that award going to a good film), and Jim Jarmusch's Stranger Than Paradise came out, becoming by far the biggest critical success of the indie scene, and the first film to make people seriously start talking about the artistic promise of these new "indie movies". Blood Simple came out at a perfect time to capitalise on this newfound (relatively) mainstream interest in films that were taking advantage of the new freedoms, telling weirdo outsider stories set in odd little corners of the world. The film made a little profit and was enthusiastically celebrated by virtually every important American critic.

And why shouldn't it be? Blood Simple is a remarkable debut film by two directors (only one of them, Joel, receiving credit, due to DGA rules; this would remain their arrangement for 20 years) with an obvious, intuitive understanding for crafting movie imagery - and this is, make no mistake, a movie, the kind of thing that gets made by people who've spent years soaking up the vivid pleasures of film noir and approached the craft not through the art scene lens of most of the New York-based indie directors of that generation, but through the seedy world of genre film. For Joel Coen had gotten his professional start as an assistant editor on Sam Raimi's grungy and repulsive 1981 independent horror masterwork The Evil Dead, and both Coens took Raimi as something as a mentor, going so far as to copy his "make a trailer and show that to potential investors" trick when they were looking to finance Blood Simple.

There is, in fact, a great deal of Raimi in Blood Simple, more than there is of the future Coens, I would say. It's not a horror film, but it has several scenes that draw from horror iconography, and many of the camera positions, camera movements, and insert shots feel very much in line with the claustrophobic, violence-obsessed rhythms of Raimi's film, and especially the gliding, probing, stalking camera that Raimi used to such great effect in The Evil Dead and several of his other movies for years to come. The horror influence on Blood Simple is, I think, easy to overlook, in part because it's a mode that the Coen brothers never worked in again, save for the climax of their fourth movie, 1991's Barton Fink. But it's front and center in the two most aggressively exciting and showily impressive moments of the film. The second of these is the final stand-off, in which a character trapped behind a wall shoots through it, creating spooky beams of light in the dark room on the other side of that wall, as bright white holes appear in a pitch-black space.

The first is the sequence that has been, since 1984, the film's calling card, an inordinately long, wordless sequence during which time a man prepares to bury a dead body, and finds to his immense shock and terror that the body isn't quite as dead as all that. It's particularly impressive in that the film manages to have it both ways: it's horrifying for the man disposing of the body, since he sees the victim crawling painfully down the highway in the harsh beam of the car's headlights with the dazed alarm that we might look at the shuffling undead in a zombie movie; it's horrifying for the man being buried because he is, after all, being buried alive, and the fragmentary way that the burial has been cut together (the Coens themselves, working under the pseudonym Roderick Jaynes, edited the film with Don Wiegmann), as a series of close-ups, makes it all feel very helpless and implacable, especially at the end, with the jarring shot of a shovel being smacked hard against the loose earth to pack it down. It's all the more impressive given that neither of these characters has been particularly sympathetic up to this point (there is, in fact, no genuinely sympathetic figure in Blood Simple, setting up the pervasive criticism of the Coens that they're inhumane nihilists who hate their characters. We'll get there in a minute). It's a brilliant reel-long exercise in tension giving way to miserable weariness, echoing the long central sequence of Psycho where Norman disposes of the evidence of Mother's crime, and it's maybe the single most successful knock-off of that sequence I've ever seen: the way it's dragged out becomes so immensely draining and horrible to look at, but the inky visuals of Barry Sonnenfeld's cinematography and the sharp, propulsive rhythm of the cutting make it exciting and evocative even so. It's the most brutal single sequence in any Coen film until No Country for Old Men, almost a quarter of a century later: brutal not because of what it depicts, but because of its refusal to blink or look away, forcing us to just with with the moment in all its pathetic amorality.

Bravura filmmaking no matter what, even if it's not exactly bravura filmmaking in the Coen brothers mold. We get much more of that in the writing than in the filmmaking, honestly, notwithstanding that tracking shot on the bar, or the way a gently rotting pile of fish on a desk keep serving as the centerpiece to compositions, sardonically reflecting the development of the narrative with a sense of black humor that the film is generally a little bit too willing to swallow down (it is this, more than anything else, that keeps it from feeling properly "Coenesque"). The story is both pure film noir and a great foreshadowing of the director's work to come: it's basically a story about how everybody ends up making mistakes that cause them to act in a fashion directly opposed to their own best interests. Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya) owns a bar, where he employs Ray (John Getz), who is sleeping with Marty's much younger wife Abby (Frances McDormand). He hires private detective Loren Visser (M. Emmet Walsh) to prove it, and then later to kill Ray and Abby; this is where things get really fun, as Visser kills Marty and frames Abby, convincing Ray to hide the body (that scene), which then convinces Abby that Ray committed the crime. It's a comedy of errors, only presented with doomy fatalism that speaks the idea of being "blood simple" (a phrase never explained in the 1998 cut), so panicked over death and violence that one starts making the wrong choices almost compulsively.

Characters immediately getting in over their heads and triggering a wave of events that indiscriminately punish the good and bad alike is the closest thing to a thematic throughline that we're ever going to get in the Coens' filmography, so it makes sense that it shows up right from the start. The mood is still more '40s crime novel than the ironic dark comedies that the brothers would make their specialty in the very near future: one of the peculiarities of Blood Simple is that it feels like it was written to be funnier than it actually is, like they lost their nerve. The cast treats lines that Fargo or Barton Fink would inject with some sick ironic humor in a perfectly straightforward way, helping to propel the film into its no-way-out noir fatalism without any whisper of absurdity. In this respect, Walsh is the only actor who feels like he completely "gets" the movie, chewing into the arbitrary, smug nastiness of the role with toad-like self-amusement and a willingness to look sweaty and slimy and dirty even by the standards of a film that is dominated by sweat. He gets the film's opening monologue, a bit of local color dialect and nihilistic poetry over dreamy shots of the Texas landscape, thus setting the tone for the whole movie (much better than its first proper scene, in which McDormand and Getz awkwardly overdub their lines in a pointedly ambiguous car-driving scene where we never see their faces); he's also the last person we see, and his bug-eyed stare in that shot gets at the combination of cartoon caricature and menace that makes his character such a vivid psychopath and colorful figure: he's always scarier more than he is funny, but he is funny, or at least remarkably big and expressive in a film that's mostly content to carve things close to the bone and favor thriller intensity over anything shaggier.

This is hindsight talking, of course. Blood Simple might be "just" a crime thriller with horror overtones, but it's a pretty excellent one, anchored not just by the Coens' willingness to go dark, but by the gorgeous neon-tinged Texas nights of Sonnenfeld's cinematography, and the lonely sounds of Carter Burwell's piano score. I do not have the vocabulary to describe it, but in his amazing main theme, Burwell creates this kind of pensive uncertain melody, one that ascends very quickly and stops suddenly and then kind of drifts back - it is the music of lonely Texas roads and a sense of death hovering over them, and even considering the astronomically high quality of his enormously productive collaboration with the Coens going forward, this is one of the best things he composed for them, quiet and forlorn and just a little dangerous.

The point being: Blood Simple is an exciting, tense thriller, one whose fundamental nihilism never seems like too much thanks to how crisply etched the characters are, and how much it feels like we're on a ride alongside them. Only by the standards of the Coens' subsquent career can this possibly be scored even a mild disappointment; it's one of the boldest debuts and most watchable indie movies of the 1980s, a confident indulgence in neo-noir attitude that earns it more than just about any post-'70s neo-noir I can name. That the filmmakers would improve upon this almost immediately is far more testatment to their skill than a sign that this is doing anything wrong.

But there I go, doing the thing I promised myself not to do, which is treating Blood Simple like it's only good precisely insofar as it anticipates the Coen filmography to come. Far more fair, and far more honest, to look at it in its proper context of 1984, when American independent filmmaking was just starting to wake up: the Sundance Institute took over the US Film and Video Festival and prepared to rebrand it as a major focal point for independent cinema (Blood Simple would win the Grand Jury Prize at the 1985 festival, in a vanishingly rare example of that award going to a good film), and Jim Jarmusch's Stranger Than Paradise came out, becoming by far the biggest critical success of the indie scene, and the first film to make people seriously start talking about the artistic promise of these new "indie movies". Blood Simple came out at a perfect time to capitalise on this newfound (relatively) mainstream interest in films that were taking advantage of the new freedoms, telling weirdo outsider stories set in odd little corners of the world. The film made a little profit and was enthusiastically celebrated by virtually every important American critic.

And why shouldn't it be? Blood Simple is a remarkable debut film by two directors (only one of them, Joel, receiving credit, due to DGA rules; this would remain their arrangement for 20 years) with an obvious, intuitive understanding for crafting movie imagery - and this is, make no mistake, a movie, the kind of thing that gets made by people who've spent years soaking up the vivid pleasures of film noir and approached the craft not through the art scene lens of most of the New York-based indie directors of that generation, but through the seedy world of genre film. For Joel Coen had gotten his professional start as an assistant editor on Sam Raimi's grungy and repulsive 1981 independent horror masterwork The Evil Dead, and both Coens took Raimi as something as a mentor, going so far as to copy his "make a trailer and show that to potential investors" trick when they were looking to finance Blood Simple.

There is, in fact, a great deal of Raimi in Blood Simple, more than there is of the future Coens, I would say. It's not a horror film, but it has several scenes that draw from horror iconography, and many of the camera positions, camera movements, and insert shots feel very much in line with the claustrophobic, violence-obsessed rhythms of Raimi's film, and especially the gliding, probing, stalking camera that Raimi used to such great effect in The Evil Dead and several of his other movies for years to come. The horror influence on Blood Simple is, I think, easy to overlook, in part because it's a mode that the Coen brothers never worked in again, save for the climax of their fourth movie, 1991's Barton Fink. But it's front and center in the two most aggressively exciting and showily impressive moments of the film. The second of these is the final stand-off, in which a character trapped behind a wall shoots through it, creating spooky beams of light in the dark room on the other side of that wall, as bright white holes appear in a pitch-black space.

The first is the sequence that has been, since 1984, the film's calling card, an inordinately long, wordless sequence during which time a man prepares to bury a dead body, and finds to his immense shock and terror that the body isn't quite as dead as all that. It's particularly impressive in that the film manages to have it both ways: it's horrifying for the man disposing of the body, since he sees the victim crawling painfully down the highway in the harsh beam of the car's headlights with the dazed alarm that we might look at the shuffling undead in a zombie movie; it's horrifying for the man being buried because he is, after all, being buried alive, and the fragmentary way that the burial has been cut together (the Coens themselves, working under the pseudonym Roderick Jaynes, edited the film with Don Wiegmann), as a series of close-ups, makes it all feel very helpless and implacable, especially at the end, with the jarring shot of a shovel being smacked hard against the loose earth to pack it down. It's all the more impressive given that neither of these characters has been particularly sympathetic up to this point (there is, in fact, no genuinely sympathetic figure in Blood Simple, setting up the pervasive criticism of the Coens that they're inhumane nihilists who hate their characters. We'll get there in a minute). It's a brilliant reel-long exercise in tension giving way to miserable weariness, echoing the long central sequence of Psycho where Norman disposes of the evidence of Mother's crime, and it's maybe the single most successful knock-off of that sequence I've ever seen: the way it's dragged out becomes so immensely draining and horrible to look at, but the inky visuals of Barry Sonnenfeld's cinematography and the sharp, propulsive rhythm of the cutting make it exciting and evocative even so. It's the most brutal single sequence in any Coen film until No Country for Old Men, almost a quarter of a century later: brutal not because of what it depicts, but because of its refusal to blink or look away, forcing us to just with with the moment in all its pathetic amorality.

Bravura filmmaking no matter what, even if it's not exactly bravura filmmaking in the Coen brothers mold. We get much more of that in the writing than in the filmmaking, honestly, notwithstanding that tracking shot on the bar, or the way a gently rotting pile of fish on a desk keep serving as the centerpiece to compositions, sardonically reflecting the development of the narrative with a sense of black humor that the film is generally a little bit too willing to swallow down (it is this, more than anything else, that keeps it from feeling properly "Coenesque"). The story is both pure film noir and a great foreshadowing of the director's work to come: it's basically a story about how everybody ends up making mistakes that cause them to act in a fashion directly opposed to their own best interests. Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya) owns a bar, where he employs Ray (John Getz), who is sleeping with Marty's much younger wife Abby (Frances McDormand). He hires private detective Loren Visser (M. Emmet Walsh) to prove it, and then later to kill Ray and Abby; this is where things get really fun, as Visser kills Marty and frames Abby, convincing Ray to hide the body (that scene), which then convinces Abby that Ray committed the crime. It's a comedy of errors, only presented with doomy fatalism that speaks the idea of being "blood simple" (a phrase never explained in the 1998 cut), so panicked over death and violence that one starts making the wrong choices almost compulsively.

Characters immediately getting in over their heads and triggering a wave of events that indiscriminately punish the good and bad alike is the closest thing to a thematic throughline that we're ever going to get in the Coens' filmography, so it makes sense that it shows up right from the start. The mood is still more '40s crime novel than the ironic dark comedies that the brothers would make their specialty in the very near future: one of the peculiarities of Blood Simple is that it feels like it was written to be funnier than it actually is, like they lost their nerve. The cast treats lines that Fargo or Barton Fink would inject with some sick ironic humor in a perfectly straightforward way, helping to propel the film into its no-way-out noir fatalism without any whisper of absurdity. In this respect, Walsh is the only actor who feels like he completely "gets" the movie, chewing into the arbitrary, smug nastiness of the role with toad-like self-amusement and a willingness to look sweaty and slimy and dirty even by the standards of a film that is dominated by sweat. He gets the film's opening monologue, a bit of local color dialect and nihilistic poetry over dreamy shots of the Texas landscape, thus setting the tone for the whole movie (much better than its first proper scene, in which McDormand and Getz awkwardly overdub their lines in a pointedly ambiguous car-driving scene where we never see their faces); he's also the last person we see, and his bug-eyed stare in that shot gets at the combination of cartoon caricature and menace that makes his character such a vivid psychopath and colorful figure: he's always scarier more than he is funny, but he is funny, or at least remarkably big and expressive in a film that's mostly content to carve things close to the bone and favor thriller intensity over anything shaggier.

This is hindsight talking, of course. Blood Simple might be "just" a crime thriller with horror overtones, but it's a pretty excellent one, anchored not just by the Coens' willingness to go dark, but by the gorgeous neon-tinged Texas nights of Sonnenfeld's cinematography, and the lonely sounds of Carter Burwell's piano score. I do not have the vocabulary to describe it, but in his amazing main theme, Burwell creates this kind of pensive uncertain melody, one that ascends very quickly and stops suddenly and then kind of drifts back - it is the music of lonely Texas roads and a sense of death hovering over them, and even considering the astronomically high quality of his enormously productive collaboration with the Coens going forward, this is one of the best things he composed for them, quiet and forlorn and just a little dangerous.

The point being: Blood Simple is an exciting, tense thriller, one whose fundamental nihilism never seems like too much thanks to how crisply etched the characters are, and how much it feels like we're on a ride alongside them. Only by the standards of the Coens' subsquent career can this possibly be scored even a mild disappointment; it's one of the boldest debuts and most watchable indie movies of the 1980s, a confident indulgence in neo-noir attitude that earns it more than just about any post-'70s neo-noir I can name. That the filmmakers would improve upon this almost immediately is far more testatment to their skill than a sign that this is doing anything wrong.