Doppelgängsters

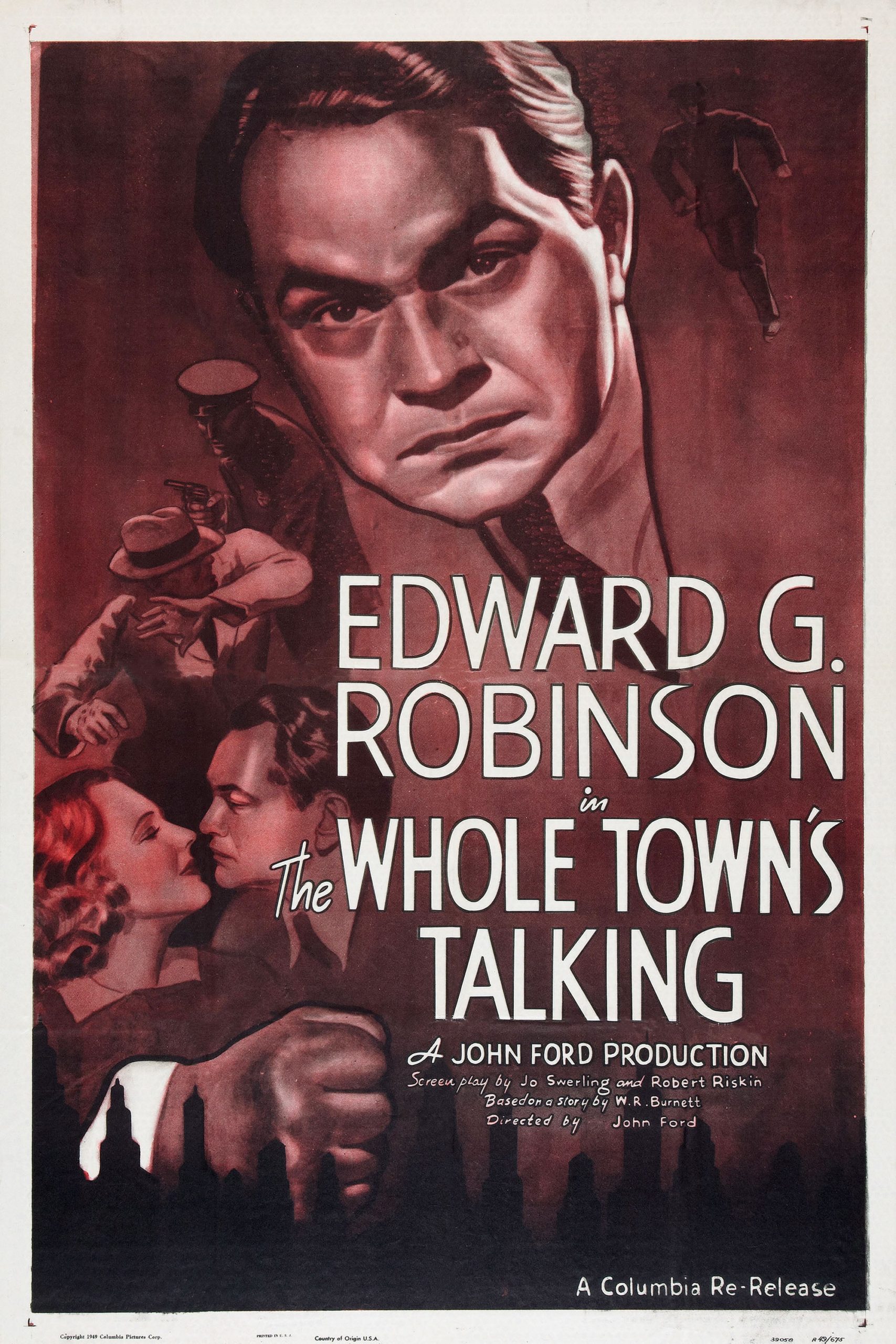

1935's The Whole Town's Talking is a weird movie. All the weirder still, because it doesn't in the slightest bit act like it's weird. But here's what we've got: a variation of The Prince and the Pauper set inside of a '30s gangster picture, that spends its first act looking for all the world like a screwball comedy. And co-star Jean Arthur never stops treating it like a screwball comedy, even as it grows increasingly dark. Also, there are echoes of a much more aggressively left-populist story about how the little guy is just trying to get through the day, and damn the bosses; and the whole thing turns out to be a distressingly grounded psychological study of a man in growing terror for his life.

And that's not even mentioning the weirdest part of all, which is that this is a film by John Ford, working miles outside of his comfort zone. This is especially true in the first act, which finds Ford doing a sort of prophetic impression of Frank Capra, though even Capra hadn't quite started making this kind of film just yet. But it has all the ingredients: it's anchored by no-nonsense Mom-like voice of reason performance by Arthur, and it shambles through its story of a workaday nobody with a comfortably loose attitude whose unfussiness itself comes across as a methodical statement of intent. It's not even unsuccessful, though it never feels entirely natural. The issue here is, I think, that the opening of The Whole Town's Talking presents one of the least Fordian things that existed in '30s cinema: urbane comedy.

Humor in Ford's films is a weird thing in general: he loved his eccentrics, caricatures, and clowns, and would dote on them even in very serious movies, often to the detriment of the films themselves (one thinks of the excruciating comedy bits in The Searchers, and recoils). Even when it works, comedy in Ford's films is big and broad, playing to the cheap seats without apology or restraint; I'll yield to no-one in my love of the philosophical drunks or zany Irishmen (or zany drunken Irish philosophers) littering Ford's filmography, but it is not because these characters are sketched out with delicacy or wit. The only exception I can immediately think of happens to be especially germane, because it was happening concurrently with The Whole Town's Talking: the run of movies Ford made with legendary radio star Will Rogers, whose humor was of a more methodical, reflective sort and whose ambling persona was a perfect fit for Ford's love of laid-back rural communities.

But the snappy, dialogue-driven, quick-thinking sort of comedy typical of urban-set '30s comedies? The kind where Arthur would go on to make her name? I can think of nothing in Ford's skill set to suggest a facility with that kind of thing, and The Whole Town's Talking doesn't convince me that I'm wrong. This is not to say that the film's first act is bad. But it's very strange. The story is about Arthur Ferguson Jones (Edward G. Robinson), a clerk in some pointless office who has been the very best worker bee on staff, never once missing a day's work since he was hired. Until, that is, today, the exact day that the big boss, J.G. Carpenter (Paul Harvey) tells fatigued officer manager Seaver (Etienne Girardot) to A) give Jones a raise, on account of his sterling behavior; B) fire the next person who shows up late, no excuses, no hesitation. When Jones shows up late, having slept in thanks to a faulty new alarm clock, and dreaming about his hoped-for writing career, Seaver is in quite a pickle. Luckily, the film now introduces a brand new plotline that completely overwrites absolutely everything I've just said. Which is one of the weirdest parts of this weird movie - it clearly wants to find a way to work in a little fable about the everyday works who make the country go in those days of the Depression, and point out that bosses are monstrous assholes, but it apparently couldn't find a way to do that within the actual story it was telling.

That story is about how Jones is a dead ringer for recently escaped gangster "Killer" Mannion (Robinson also), and as a result, our hero gets nabbed by the police. By the time everything is sorted out, he's been contracted by a local paper to give his name to a series of ghostwritten articles about Mannion, and a piece of paper signed by the district attorney that gives him free passage. That same night, Mannion shows up in Jones's apartment, demanding that letter, and threatening the clerk into a sort of hideous identity timeshare, where Mannion will live in Jones's home and pretend to be him, and continue his reign of terror. Throughout this, Jones's whip-smart coworker and crush, Wilhelmina Clark (Arthur), gets herself right in the middle of the two men, not realising that they are two men.

As written by two aces like Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin (both of whom worked with Capra, the latter extensively), this somehow all hangs together, no matter how much it looks like it shouldn't. But I still shouldn't like to see how this would have turned out without Robinson in the central role(s) - if the writers lay in a plot that can survive its baffling turn from screwball comedy to gangster thriller, Robinson's performance is the primary reason that it does survive. He does this largely by underplaying the opening sequence; his Jones is an extremely small and nervous personality (a great change of pace from the snarling tough guys that had already become his stock persona, and probably close to the actual Robinson), quiet and with a speaking voice that has a calm warmth to it that suggests not wisdom or maturity, but a lifetime of giving up. Basically, Robinson makes all of this work by introducing sadness into the zippy comedy of the opening act; not enough to overwhelm it, not even enough that I'm sure that I'd have noticed it, if it didn't pay off later. But it does pay off later, and that slight melancholy tone he reads into the film early on provides a tether for when it becomes more expressly a character drama.

And this it certainly does, right about the moment that Mannion shows up in Jones's home. This is also where the film starts to feel comfortable, shedding its somewhat hard-working comic bounce in favor of focusing like a laser on Jones's reaction to being in constant mortal danger. It's still not in Ford's wheelhouse - he's not a gangster director any more than he's an urbane comedy director - but the director and the star work hard to rebuild the movie around Jones's descent into terror, and it ends up working extremely well. Plus, the ambition with which Ford stages the two Robinsons, incorporating a complicated mirror set-up at one point, seems like the kind of technical challenge that inspired him to be his best self, finding ways of pitting the actor against himself in the frame in a way that turns the film into a tough battle of wills that thankfully steers clear of lump symbolism. The visual tension generated between the two figures amplifies the tension Robinson already brings to his two extremely different approaches.

It's still a light-touch genre movie, so I don't want to oversell how harrowing and intense it gets, but Robinson's portrayal of Jones isn't even slightly afraid to get dark, showing how the all-encompassing fear of death can break a man who had already come somewhat pre-broken. Jones is no hero, and the feelings of anxiety and confusion and despair that Robinson reads into him are genuinely moving. There is something Fordian about this: the man alone, forced to survive based only on the character he already has within him, and finding that he doesn't actually have much. The two films couldn't be farther apart thematically or tonally, but as a character piece, The Whole Town's Talking matches oddly well with one of Ford's other 1935 releases, The Informer: it's a sunnier and more charming version of that film's story about a man tormented and isolated by his cowardice. Enough so that, even though the film bills itself as a comedy, and Robinson's other performance as Mannion resides securely in the realm of self-parody, there's not much in the second half of The Whole Town's Talking that's very funny. It's delicate and light, in a way that the crushing The Informer never thinks of being, but it's still, ultimately, about a man crippled by fear.

This doesn't end up working flawlessly: it's still written as a comedy, and this includes a comedy-style ending that feels much too rushed and convenient for the way the film has developed. And there's very little room for Arthur in this more sober, even grim character work, but the film has decided that she's the romantic interest, so room will necessarily be made. The best that could be said is that it's a fun movie for classic Hollywood buffs, a great showpiece for Robinson and one of the most offbeat curios in Ford's jam-packed filmography. As an unabashed lover of '30s Hollywood, Robinson, and Ford, I was captivated; others may wish to tread cautiously.

And that's not even mentioning the weirdest part of all, which is that this is a film by John Ford, working miles outside of his comfort zone. This is especially true in the first act, which finds Ford doing a sort of prophetic impression of Frank Capra, though even Capra hadn't quite started making this kind of film just yet. But it has all the ingredients: it's anchored by no-nonsense Mom-like voice of reason performance by Arthur, and it shambles through its story of a workaday nobody with a comfortably loose attitude whose unfussiness itself comes across as a methodical statement of intent. It's not even unsuccessful, though it never feels entirely natural. The issue here is, I think, that the opening of The Whole Town's Talking presents one of the least Fordian things that existed in '30s cinema: urbane comedy.

Humor in Ford's films is a weird thing in general: he loved his eccentrics, caricatures, and clowns, and would dote on them even in very serious movies, often to the detriment of the films themselves (one thinks of the excruciating comedy bits in The Searchers, and recoils). Even when it works, comedy in Ford's films is big and broad, playing to the cheap seats without apology or restraint; I'll yield to no-one in my love of the philosophical drunks or zany Irishmen (or zany drunken Irish philosophers) littering Ford's filmography, but it is not because these characters are sketched out with delicacy or wit. The only exception I can immediately think of happens to be especially germane, because it was happening concurrently with The Whole Town's Talking: the run of movies Ford made with legendary radio star Will Rogers, whose humor was of a more methodical, reflective sort and whose ambling persona was a perfect fit for Ford's love of laid-back rural communities.

But the snappy, dialogue-driven, quick-thinking sort of comedy typical of urban-set '30s comedies? The kind where Arthur would go on to make her name? I can think of nothing in Ford's skill set to suggest a facility with that kind of thing, and The Whole Town's Talking doesn't convince me that I'm wrong. This is not to say that the film's first act is bad. But it's very strange. The story is about Arthur Ferguson Jones (Edward G. Robinson), a clerk in some pointless office who has been the very best worker bee on staff, never once missing a day's work since he was hired. Until, that is, today, the exact day that the big boss, J.G. Carpenter (Paul Harvey) tells fatigued officer manager Seaver (Etienne Girardot) to A) give Jones a raise, on account of his sterling behavior; B) fire the next person who shows up late, no excuses, no hesitation. When Jones shows up late, having slept in thanks to a faulty new alarm clock, and dreaming about his hoped-for writing career, Seaver is in quite a pickle. Luckily, the film now introduces a brand new plotline that completely overwrites absolutely everything I've just said. Which is one of the weirdest parts of this weird movie - it clearly wants to find a way to work in a little fable about the everyday works who make the country go in those days of the Depression, and point out that bosses are monstrous assholes, but it apparently couldn't find a way to do that within the actual story it was telling.

That story is about how Jones is a dead ringer for recently escaped gangster "Killer" Mannion (Robinson also), and as a result, our hero gets nabbed by the police. By the time everything is sorted out, he's been contracted by a local paper to give his name to a series of ghostwritten articles about Mannion, and a piece of paper signed by the district attorney that gives him free passage. That same night, Mannion shows up in Jones's apartment, demanding that letter, and threatening the clerk into a sort of hideous identity timeshare, where Mannion will live in Jones's home and pretend to be him, and continue his reign of terror. Throughout this, Jones's whip-smart coworker and crush, Wilhelmina Clark (Arthur), gets herself right in the middle of the two men, not realising that they are two men.

As written by two aces like Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin (both of whom worked with Capra, the latter extensively), this somehow all hangs together, no matter how much it looks like it shouldn't. But I still shouldn't like to see how this would have turned out without Robinson in the central role(s) - if the writers lay in a plot that can survive its baffling turn from screwball comedy to gangster thriller, Robinson's performance is the primary reason that it does survive. He does this largely by underplaying the opening sequence; his Jones is an extremely small and nervous personality (a great change of pace from the snarling tough guys that had already become his stock persona, and probably close to the actual Robinson), quiet and with a speaking voice that has a calm warmth to it that suggests not wisdom or maturity, but a lifetime of giving up. Basically, Robinson makes all of this work by introducing sadness into the zippy comedy of the opening act; not enough to overwhelm it, not even enough that I'm sure that I'd have noticed it, if it didn't pay off later. But it does pay off later, and that slight melancholy tone he reads into the film early on provides a tether for when it becomes more expressly a character drama.

And this it certainly does, right about the moment that Mannion shows up in Jones's home. This is also where the film starts to feel comfortable, shedding its somewhat hard-working comic bounce in favor of focusing like a laser on Jones's reaction to being in constant mortal danger. It's still not in Ford's wheelhouse - he's not a gangster director any more than he's an urbane comedy director - but the director and the star work hard to rebuild the movie around Jones's descent into terror, and it ends up working extremely well. Plus, the ambition with which Ford stages the two Robinsons, incorporating a complicated mirror set-up at one point, seems like the kind of technical challenge that inspired him to be his best self, finding ways of pitting the actor against himself in the frame in a way that turns the film into a tough battle of wills that thankfully steers clear of lump symbolism. The visual tension generated between the two figures amplifies the tension Robinson already brings to his two extremely different approaches.

It's still a light-touch genre movie, so I don't want to oversell how harrowing and intense it gets, but Robinson's portrayal of Jones isn't even slightly afraid to get dark, showing how the all-encompassing fear of death can break a man who had already come somewhat pre-broken. Jones is no hero, and the feelings of anxiety and confusion and despair that Robinson reads into him are genuinely moving. There is something Fordian about this: the man alone, forced to survive based only on the character he already has within him, and finding that he doesn't actually have much. The two films couldn't be farther apart thematically or tonally, but as a character piece, The Whole Town's Talking matches oddly well with one of Ford's other 1935 releases, The Informer: it's a sunnier and more charming version of that film's story about a man tormented and isolated by his cowardice. Enough so that, even though the film bills itself as a comedy, and Robinson's other performance as Mannion resides securely in the realm of self-parody, there's not much in the second half of The Whole Town's Talking that's very funny. It's delicate and light, in a way that the crushing The Informer never thinks of being, but it's still, ultimately, about a man crippled by fear.

This doesn't end up working flawlessly: it's still written as a comedy, and this includes a comedy-style ending that feels much too rushed and convenient for the way the film has developed. And there's very little room for Arthur in this more sober, even grim character work, but the film has decided that she's the romantic interest, so room will necessarily be made. The best that could be said is that it's a fun movie for classic Hollywood buffs, a great showpiece for Robinson and one of the most offbeat curios in Ford's jam-packed filmography. As an unabashed lover of '30s Hollywood, Robinson, and Ford, I was captivated; others may wish to tread cautiously.

Categories: comedies, gangster pictures, hollywood in the 30s, john ford