A room of one's own

The "kitchen sink" period of British theater and cinema - stretching for a little more than ten years from the mid-'50s to the late-'60s - is, to my mind, much more "admirable" than it is "good" or "watchable". The movement was all about radicalism, violating social taboos that have long since become social norms, and unlike other, similar movements (such as the New Waves going on across Europe at the same time), many of films and plays don't have very much else to offer beyond radicalism. The plots are blunt and straightforward, the characters generally lack nuance, and these things are done on purpose, to emphasise the frustrating go-nowhere misery of the working class life on display - not for nothing were the authors who spearheaded this moment sometimes called the Angry Young Men. But radicalism often doesn't age well, and now that words like "pregnant" and "homosexual" are no longer shocking in and of themselves, a lot of the charge has gone out of these dramas. Given the pointedly artless plotting, there's generally not much of particular interest to replace it, other than strong performances by very good young actors who would mostly go on to more interesting work.

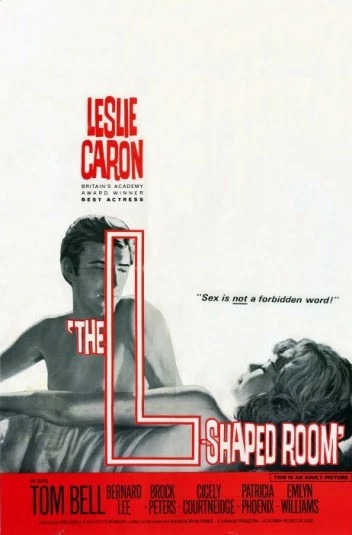

That being said, the best examples of the form are quite good indeed, and we have in front of us now my personal favorite of the kitchen sink movies, 1962's The L-Shaped Room. It's probably not a coincidence than instead of an angry young man, it has a young woman, whose emotional life is far too ambivalent and multilayered to give her a single adjective, though "angry" wouldn't even be on the list. And while it does land on some of the expected taboos - she's unmarried and pregnant, abortion is alluded to several times, one of the characters is possibly the most explicitly-coded prostitute in an English-language movie since the early 1930s, and a different character is suggested to be gay - it's not about those taboos, nor is it about the grimy agony of the working class. It's a character study of the lost souls who end up together in the same rooming house, using kitchen sink realism as the context for its story, not as the purpose of its story, and this turns out to make a huge difference.

Another difference: The L-Shaped Room was the second film directed by actor-turned-director Bryan Forbes, one of the all-time best directors of actors that you most likely haven't heard of. In addition to guiding three of the best performances in British cinema in the 1960s - Kim Stanley and Richard Attenborough in 1964's Seance on a Wet Afternoon, and Edith Evans in 1967's The Whisperers - he had a knack for helping actors who aren't necessarily the best or most reliable unlock something powerful that was hiding ride underneath their standard bag of tricks. And in The L-Shaped Room, we find a doozy: this is by an inordinately lopsided margin the best performance I've ever seen from Leslie Caron, the gamine of gamines who was introduced to cinema as the dewy-eyed, oppressively sexless female lead in the 1951 MGM musical An American in Paris. The next ten years found her playing different variations of adorable girl-women with just enough of a teasing Continental awareness of sex that they can talk about it, while exuding such an overbearing purity that one steadily refuses to believe that they could possibly mean anything by it, and that's only in the ones that are actually "about" sex, like Gigi (1958) and Fanny (1961). In the ones that aren't like Lili (1953) and Daddy Long Legs (1955), things are even worse, as Caron inhabits empty-headed baubles of innocent femininity that only the most patronising corners of the 1950s could imaginably have generated. The films are variable in quality, but Caron herself is reliably insipid, seeming to view the whole business of film acting as a charming lark that not only doesn't but indeed mustn't demand more of the movie star than offering a beaming smile in close-ups and a few well-done humorous-but-not-funny line readings.

When The L-Shaped Room premiered in November, 1962, Caron was 31 years old, which is getting a bit long in the tooth to keep playing gamines, and so we get this somewhat explicit farewell to the Gigis and Lilis and Fannys. She takes on the role of 27-year-old Jane Fosset, originally an English woman in Lynne Reid Banks's 1960 novel - as well she might be, with a name like "Jane Fosset", and having the characters pronounce her surname "Fos-SAY" doesn't really convince us otherwise. But Forbes's script does add some specific wrinkles with Jane being a foreigner that at least somewhat compensates. More to the point, Jane takes on extraordinary resonance for being embodied by Caron, the most noble virgin in '50s cinema next to Audrey Hepburn. For Jane is pregnant, and unwed, and she has come to London to figure out what to do about those things, taking up residence in a ratty boarding house owned by the blowsy Doris (Avis Bunnage). Jane's first meeting with a doctor (Emlyn Williams) goes horribly awry: he assumes, with such gregarious condescension, that she's there to have an abortion, and speaks in such mercilessly procedural terms about it, that she makes up her mind in revulsion to have the child, and all the looks of dubious superiority she gets from both men and women for the rest of the film only firm up that decision. And thus she commits to living in that grimy L-shaped room at the top of the house for the seven months of her pregnancy, falling into the rhythms of life amongst its inhabitants: unsuccessful writer Toby (Tom Bell), elliptically gay African immigrant Johnny (Brock Peters), gone-to-seed actress Mavis (Cicely Courtneidge), overworked prostitute Sonia (Patricia Phoenix).

Every name on that cast list is doing superb work, but it's Caron's show: the film spends most of its time in Jane's presence, and she's the character we side with any time there's a conflict with one of the others. As there is mostly in the fact that Toby is instantly smitten with her, and their relationship keeps running into the iceberg of his insistently conservative views on sex and single parenthood. Key to how The L-Shaped Room works, Caron isn't thrilling to toss away her persona in celebration of the bleak, downtrodden and sordid. Rather, she hones it, evolves it: if all those early characters were safely neutered fantasies, Jane is unsentimental reality. Caron thrives in this role, and under Forbes's care; she's already doing some of the most complicated work of her career as early as the doctor scene, and that's really just a functional bit of exposition that asks for none of the layering she'll do later on. When I think of her performance, it's of moments like her response to hearing Toby admit that he's on the make: a thin smile that confirms that she doesn't especially enjoy boys in general looking at her and only seeing a sex object, but she is flattered and happy that this boy does. Or her meeting with the father of her baby, full of weary line readings that are nevertheless tweaked with some irony, a sense that she regrets, most of all, that she doesn't regret this particular mistake, culminating in her phenomenal read of the too-cute line "In the end I decided my virginity was becoming rather cumbersome", almost daring us and the useless gentleman across from her to challenge the level flatness and matter-of-fact acceptance of her tone.

Caron's Jane is the natural centerpiece of the film, and she's worthy of it: the way she allows a tough, ironic exterior to only mostly cover up for a nervous uncertainty is a good symbol for the film's overall presentation of its characters, all of whom seem tougher at the start than they do at the end. This isn't a surprising arc, of course, but Forbes works to make sure that this remains free of trite cliché, as much as possible (he's not entirely successful, by the end, but the film's climax is surely impossible to render completely free from cliché, and the ambiguity of the interactions between Caron and Bell in the denouement make up for it). Largely, this is simply by coaxing the actors to all do the same kind of complicated work that Caron is doing, even with fewer scenes; The L-Shaped Room is one of those movies where every performance is so precise that you learn everything about a person just from one or two big performances. Sonia's a great example; she only really gets one big scene, but Phoenix builds so much into her chatty line deliveries and relaxed but persistent stage business that we've gotten a whole movie's worth of insight into the upbeat drudgery of her life that makes it just as piercing a window into the lives of the downtrodden as Jane's entire two-hour journey.

It's that lived-in feeling that gives this film so much of its strength; we know these people by the end, and appreciate the community they've formed, even if it's too tired of a community to meet the "they're like a family!" boilerplate that the scenario might look like from the outside. I would not want to say that the film is all about the acting: Forbes is a capable visual stylist, and the film was shot by the world-class talent Douglas Slocombe, who sculpts the boarding house in a slightly high-contrast black and white that accentuates all its dingy edges. In later films, the director would prove adept at bringing elements of a thriller into his film from unusual angles, and he's slightly playing with that in The L-Shaped Room, especially at the beginning, to accentuate Jane's unspoken nerves. Still, style here is mostly in support of realism, and realism is mostly in support of letting the characters emerge as engaging, complicated personalities. It's a lovely film without being soppy, treating the material with the lack of bullshit it needs, and it has a social conscience without screaming it at us, something more films of its generation would benefit from.

That being said, the best examples of the form are quite good indeed, and we have in front of us now my personal favorite of the kitchen sink movies, 1962's The L-Shaped Room. It's probably not a coincidence than instead of an angry young man, it has a young woman, whose emotional life is far too ambivalent and multilayered to give her a single adjective, though "angry" wouldn't even be on the list. And while it does land on some of the expected taboos - she's unmarried and pregnant, abortion is alluded to several times, one of the characters is possibly the most explicitly-coded prostitute in an English-language movie since the early 1930s, and a different character is suggested to be gay - it's not about those taboos, nor is it about the grimy agony of the working class. It's a character study of the lost souls who end up together in the same rooming house, using kitchen sink realism as the context for its story, not as the purpose of its story, and this turns out to make a huge difference.

Another difference: The L-Shaped Room was the second film directed by actor-turned-director Bryan Forbes, one of the all-time best directors of actors that you most likely haven't heard of. In addition to guiding three of the best performances in British cinema in the 1960s - Kim Stanley and Richard Attenborough in 1964's Seance on a Wet Afternoon, and Edith Evans in 1967's The Whisperers - he had a knack for helping actors who aren't necessarily the best or most reliable unlock something powerful that was hiding ride underneath their standard bag of tricks. And in The L-Shaped Room, we find a doozy: this is by an inordinately lopsided margin the best performance I've ever seen from Leslie Caron, the gamine of gamines who was introduced to cinema as the dewy-eyed, oppressively sexless female lead in the 1951 MGM musical An American in Paris. The next ten years found her playing different variations of adorable girl-women with just enough of a teasing Continental awareness of sex that they can talk about it, while exuding such an overbearing purity that one steadily refuses to believe that they could possibly mean anything by it, and that's only in the ones that are actually "about" sex, like Gigi (1958) and Fanny (1961). In the ones that aren't like Lili (1953) and Daddy Long Legs (1955), things are even worse, as Caron inhabits empty-headed baubles of innocent femininity that only the most patronising corners of the 1950s could imaginably have generated. The films are variable in quality, but Caron herself is reliably insipid, seeming to view the whole business of film acting as a charming lark that not only doesn't but indeed mustn't demand more of the movie star than offering a beaming smile in close-ups and a few well-done humorous-but-not-funny line readings.

When The L-Shaped Room premiered in November, 1962, Caron was 31 years old, which is getting a bit long in the tooth to keep playing gamines, and so we get this somewhat explicit farewell to the Gigis and Lilis and Fannys. She takes on the role of 27-year-old Jane Fosset, originally an English woman in Lynne Reid Banks's 1960 novel - as well she might be, with a name like "Jane Fosset", and having the characters pronounce her surname "Fos-SAY" doesn't really convince us otherwise. But Forbes's script does add some specific wrinkles with Jane being a foreigner that at least somewhat compensates. More to the point, Jane takes on extraordinary resonance for being embodied by Caron, the most noble virgin in '50s cinema next to Audrey Hepburn. For Jane is pregnant, and unwed, and she has come to London to figure out what to do about those things, taking up residence in a ratty boarding house owned by the blowsy Doris (Avis Bunnage). Jane's first meeting with a doctor (Emlyn Williams) goes horribly awry: he assumes, with such gregarious condescension, that she's there to have an abortion, and speaks in such mercilessly procedural terms about it, that she makes up her mind in revulsion to have the child, and all the looks of dubious superiority she gets from both men and women for the rest of the film only firm up that decision. And thus she commits to living in that grimy L-shaped room at the top of the house for the seven months of her pregnancy, falling into the rhythms of life amongst its inhabitants: unsuccessful writer Toby (Tom Bell), elliptically gay African immigrant Johnny (Brock Peters), gone-to-seed actress Mavis (Cicely Courtneidge), overworked prostitute Sonia (Patricia Phoenix).

Every name on that cast list is doing superb work, but it's Caron's show: the film spends most of its time in Jane's presence, and she's the character we side with any time there's a conflict with one of the others. As there is mostly in the fact that Toby is instantly smitten with her, and their relationship keeps running into the iceberg of his insistently conservative views on sex and single parenthood. Key to how The L-Shaped Room works, Caron isn't thrilling to toss away her persona in celebration of the bleak, downtrodden and sordid. Rather, she hones it, evolves it: if all those early characters were safely neutered fantasies, Jane is unsentimental reality. Caron thrives in this role, and under Forbes's care; she's already doing some of the most complicated work of her career as early as the doctor scene, and that's really just a functional bit of exposition that asks for none of the layering she'll do later on. When I think of her performance, it's of moments like her response to hearing Toby admit that he's on the make: a thin smile that confirms that she doesn't especially enjoy boys in general looking at her and only seeing a sex object, but she is flattered and happy that this boy does. Or her meeting with the father of her baby, full of weary line readings that are nevertheless tweaked with some irony, a sense that she regrets, most of all, that she doesn't regret this particular mistake, culminating in her phenomenal read of the too-cute line "In the end I decided my virginity was becoming rather cumbersome", almost daring us and the useless gentleman across from her to challenge the level flatness and matter-of-fact acceptance of her tone.

Caron's Jane is the natural centerpiece of the film, and she's worthy of it: the way she allows a tough, ironic exterior to only mostly cover up for a nervous uncertainty is a good symbol for the film's overall presentation of its characters, all of whom seem tougher at the start than they do at the end. This isn't a surprising arc, of course, but Forbes works to make sure that this remains free of trite cliché, as much as possible (he's not entirely successful, by the end, but the film's climax is surely impossible to render completely free from cliché, and the ambiguity of the interactions between Caron and Bell in the denouement make up for it). Largely, this is simply by coaxing the actors to all do the same kind of complicated work that Caron is doing, even with fewer scenes; The L-Shaped Room is one of those movies where every performance is so precise that you learn everything about a person just from one or two big performances. Sonia's a great example; she only really gets one big scene, but Phoenix builds so much into her chatty line deliveries and relaxed but persistent stage business that we've gotten a whole movie's worth of insight into the upbeat drudgery of her life that makes it just as piercing a window into the lives of the downtrodden as Jane's entire two-hour journey.

It's that lived-in feeling that gives this film so much of its strength; we know these people by the end, and appreciate the community they've formed, even if it's too tired of a community to meet the "they're like a family!" boilerplate that the scenario might look like from the outside. I would not want to say that the film is all about the acting: Forbes is a capable visual stylist, and the film was shot by the world-class talent Douglas Slocombe, who sculpts the boarding house in a slightly high-contrast black and white that accentuates all its dingy edges. In later films, the director would prove adept at bringing elements of a thriller into his film from unusual angles, and he's slightly playing with that in The L-Shaped Room, especially at the beginning, to accentuate Jane's unspoken nerves. Still, style here is mostly in support of realism, and realism is mostly in support of letting the characters emerge as engaging, complicated personalities. It's a lovely film without being soppy, treating the material with the lack of bullshit it needs, and it has a social conscience without screaming it at us, something more films of its generation would benefit from.

Categories: british cinema, domestic dramas