The Devil is a woman

Stories disagree on what, exactly, is up with Simon of the Desert. The received wisdom is that the funding got slashed during production, and so director-writer Luis Buñuel had to come up with a way to end the movie on the spot, using the last day to quickly tie things off of what ended up a 45-minute movie. Later, in interviews, Buñuel suggested that the missing material was all detatchable interstitial material, and that the movie we've got is in all essentials the movie he wanted to make, just condensed down. Co-star Silvia Pinal claimed that he made exactly the movie he wanted, and the rest of the running time was to have been made up of different stories, possibly by other directors, though this squares with nothing else we know of the film's production.

Whatever the case, we have before us a 45-minute motion picture whose last 5 minutes feel pretty much exactly what happens if, deprived of the ability to end a story in a sane, natural way, a filmmaker decides to end it in the most insane, inexplicable, bizarre way he can come up with at short notice. It's quite terrific, anyways, and while there's no denying that the stuffing has been pulled out of the movie in some indefinite but unmistakable way, the trade-off is that those 45 minutes are so tight and focused that the movie blazes by in a single flurry of deranged darkly comic activity, leaving almost no impression of duration at all: there's just a quick series of sharp punches and then it's over.

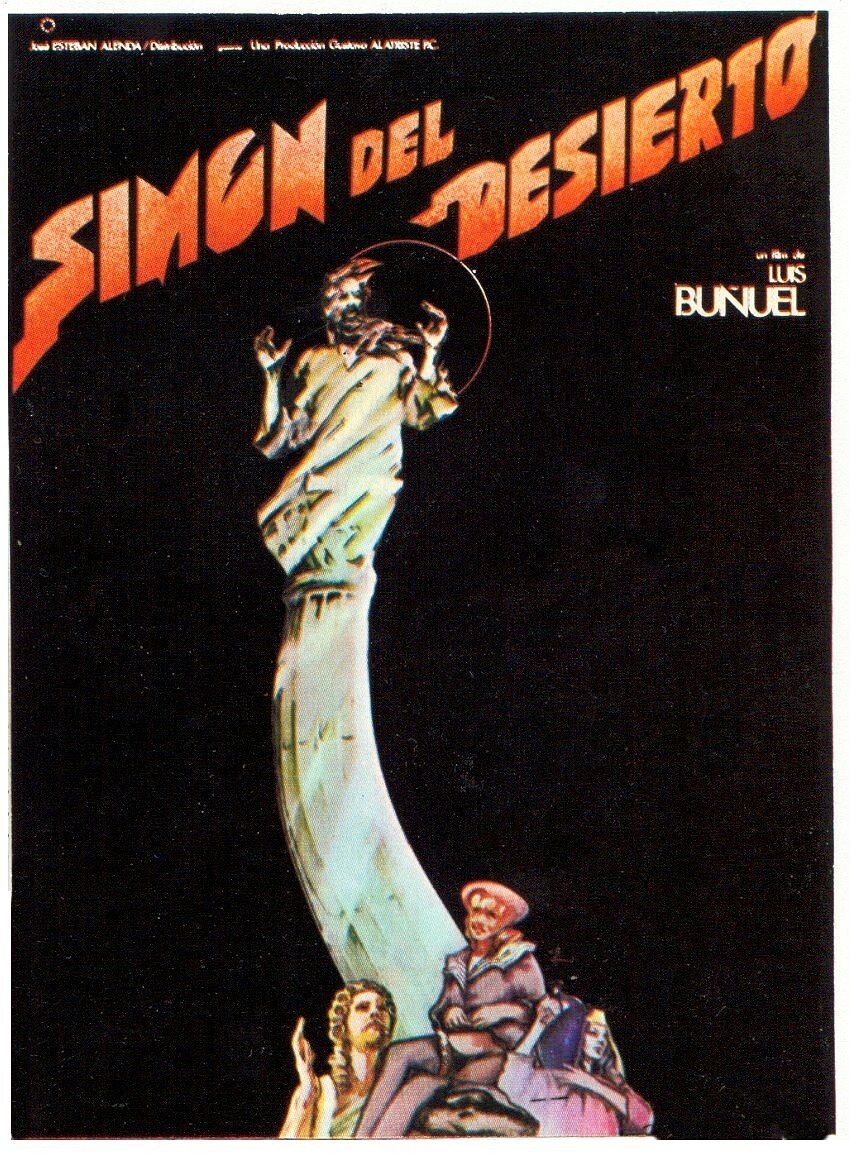

The story is more of a sketch than a full-fledged narrative; a fable might be a better word. Or, to cut right to the chase, it feels like a narrative from the Gospels, presenting just the important beats of the events it depicts without going into much detail about how those events evolve out of each other. In any case, the story is based on the life of the 5th Century Syrian ascetic Simeon Stylites, who lived for decades atop a pillar near Aleppo, both as a means of proving his willingness to suffer for God, and to get away from the crowds of pilgrim seeking his counsel. To this, Buñuel and co-writer Julio Alejandro add the biblical account of Satan tempting Jesus in the wilderness, and there's not really room for anything else. We meet Simon (Claudio Brook) on the sixth day of the sixth month of the sixth year of his time on the pillar (in other words, 666), the same day that a group of priests and monks arrive with the good news that they've bought him an even bigger pillar, in recognition of how good he is at punishing himself. As Simon crosses the desert scrub to climb up to his new home, he makes a point of repudiating his mother (Hortensia Santoveña), and beseeching God to restore the hands of a double-amputee (Enrique de Castillo); the first thing this man does with his miraculously restored body is to smack his daughter alongside the head.

Back up on the pillar, Simon is all ready to not enjoy his solitude, when a woman (Silvia Pinal) comes along, dressed like Shirley Temple singing about the Good Ship Lollipop. He figures out pretty quickly that she's in fact the Devil, and she - he - it? - doesn't care much about the surprise being spoiled, as long as Simon is willing to renounce God and climb back down to earth. The Devil comes along to do this a total of three times, finally getting pissed enough that she- but that is the film's best surprise.

Simon of the Desert is the third in a sequence of three films Buñuel made with Pinal and Brook (though he was only in small roles in the other two) and producer Gustavo Alatriste, Pinal's husband; the first two were Viridiana in 1961 and The Exterminating Angel in 1962. Taken together, they represent the most aggressive and anti-Catholic films of the director's career - Viridiana, famously, so wrathfully targets Church hierarchy and its relationship to temporal power structures that he got re-exiled from Franco's Spain after returning home for the first time in many years just to make it. The Exterminating Angel and Simon of the Desert found him back in Mexico, where he'd spent his entire post-war career, making the majority of the films he'd ever direct. Simon of the Desert was, in fact, his last Mexican film; the year prior, he made Diary of a Chambermaid in France, and it was to France he'd return to end his career on what is probably his best-known run of films.

Simon of the Desert is thus something of his farewell to the Mexican phase of his career, to black-and-white filmmaking, and to this spate of raging anti-Catholic, anti-Christian satires. For that's the glue unifying the Pinal-Alatriste-Brook films: all of them involve referencing and perverting traditional Christian iconography. This was hardly new territory for the director of the notorious L'âge d'or, but it's not really to be found much in his '40s and '50s Mexican films, certainly not to the extent of total warfare against Buñuel's Catholic upbringing, as we see in the '60s films (extending to the French The Milky Way, from 1969, but it feels of a different kind from the others - Pinal's absence is noted, as is the presence of color). Simon of the Desert is much less of a full-throated assault on norms and decency than its predecessors; it's clear even without the evidence of later interviews that Buñuel has a distinct admiration for Simon, or at least for his zealous commitment in the face of all rationality. The film is more than willing to let Simon's shabbier side get some sunlight; this is, after all, story that begins with what amounts to an army of groupies and the gift of a fancy new pillar - a strange sort of worldly possession, but a worldly possession all the same. It's still a satire against the hypocrisies of the Church, its relationship to the saints, and its love for fancy trappings while preaching the need to avoid giving into fleshy desires, and Simon is implicated in all that.

Even so, he's treated fairly by the film. Gabriel Figueroa's camera (this his last film with Buñuel after a substantial and successful collaboration) regards Brook's face with reserved awe. He's incorporated into the film's overall scheme of a wide range of greys and almost no hard blacks, creating a smeary space where the sky and the ground don't have a very clear distinction between them, giving the world more the feeling of a continuum that Brook's craggy faced is eased into, without being exaggerated to look grotesque in the way of such a large number of Buñuel characters. Pinal stands out more, creating a bit of a contrast, especially in her first and third appearance, either wearing black clothes, or riding in a black coffin that scuttles over the rocks like a lizard. And that contrast is confirmed by the way that Brook's solid performance clashes with Pinal's exaggerated, comically warped work as an oversexed little girl, an androgynous, Christlike shepherd, and finally an annoyed, angry brat.

The film is still willing to poke fun, in its extremely dry way, at the fundamental hypocritical conflict of Simon's character: he's extremely proud of how humble he is. But I can't shake the sense that Buñuel likes him - certainly more than the vulgarities of The Exterminating Angel! And for that reason, Simon of the Desert doesn't bite as hard, nor are its teeth so sharp, as the director's most aggressive films. It still has surrealist touches, mostly surrounding the Devil's changing outfits and ability to move impossibly thanks to the help of film editing, and the final sequence is a huge swerve into grimly hilarious absurdity, as Buñuel finds an unexpectedly hostile answer to the question of what a 5th Century ascetic would think Hell to be like. But its primary mode is much less one of extremes and exaggeration, than of a spare, clean style, anchored in those smooth greys. Helped, no doubt, by a short running time, the filmmakers are able to make the extremely small number of visual options (on the pillar looking down, below the pillar looking up, on the pillar looking out) feel varied enough that there are almost no obvious repeated shots, and the grey-on-grey aesthetic keeps feeling beautifully hazy, rather than drab.

The point being, there's a certain austerity to the film's aesthetic that sets it apart from all of the other late Buñuel that I've seen. Pauline Kael astutely pointed out that by emptying out the film of so much other than the essentials - sky, earth, the pillar, Brook, Pinal -Simon of the Desert amplifies the sense that it takes place in fable-time, and I can't think of a better way to look at it than that.

The fable-like mood, coupled with Buñuel's willingness to watch Simon rather than simply mock him, give this film's satire a noticeable different edge than the director's other '60s films. Those are all about the gleeful rage of a man who escaped, turning around to attack the forces he sees ruining the world with all the outrage he can muster. This is more warm and nostaglic in its rejection of Catholicism; the closest any of Buñuel's films come to match the irony of his famous sentiment "Thank God I'm an atheist". Yes, the Church is full of people who'd rather mindlessly praise saints than grapple with their own thoughts and behavior; yes, people who want to make a big show about being seen practicing humility and good works are hypocrites; yes, the Church is an ancient institution with no ability to function in the modern world, reacting with sullen annoyance that it can't go back to the 5th Century where everything made more sense (that's the most I have to say about the ending). But also, you can see why people still like to have it in their lives. This is still more satiric and mocking than otherwise - Buñuel isn't thinking about returning to the Church, or anything like that - but it's mockery that comes from something a bit closer to love than I'm used to from this director, and there's something unexpectedly pleasant about that.

Whatever the case, we have before us a 45-minute motion picture whose last 5 minutes feel pretty much exactly what happens if, deprived of the ability to end a story in a sane, natural way, a filmmaker decides to end it in the most insane, inexplicable, bizarre way he can come up with at short notice. It's quite terrific, anyways, and while there's no denying that the stuffing has been pulled out of the movie in some indefinite but unmistakable way, the trade-off is that those 45 minutes are so tight and focused that the movie blazes by in a single flurry of deranged darkly comic activity, leaving almost no impression of duration at all: there's just a quick series of sharp punches and then it's over.

The story is more of a sketch than a full-fledged narrative; a fable might be a better word. Or, to cut right to the chase, it feels like a narrative from the Gospels, presenting just the important beats of the events it depicts without going into much detail about how those events evolve out of each other. In any case, the story is based on the life of the 5th Century Syrian ascetic Simeon Stylites, who lived for decades atop a pillar near Aleppo, both as a means of proving his willingness to suffer for God, and to get away from the crowds of pilgrim seeking his counsel. To this, Buñuel and co-writer Julio Alejandro add the biblical account of Satan tempting Jesus in the wilderness, and there's not really room for anything else. We meet Simon (Claudio Brook) on the sixth day of the sixth month of the sixth year of his time on the pillar (in other words, 666), the same day that a group of priests and monks arrive with the good news that they've bought him an even bigger pillar, in recognition of how good he is at punishing himself. As Simon crosses the desert scrub to climb up to his new home, he makes a point of repudiating his mother (Hortensia Santoveña), and beseeching God to restore the hands of a double-amputee (Enrique de Castillo); the first thing this man does with his miraculously restored body is to smack his daughter alongside the head.

Back up on the pillar, Simon is all ready to not enjoy his solitude, when a woman (Silvia Pinal) comes along, dressed like Shirley Temple singing about the Good Ship Lollipop. He figures out pretty quickly that she's in fact the Devil, and she - he - it? - doesn't care much about the surprise being spoiled, as long as Simon is willing to renounce God and climb back down to earth. The Devil comes along to do this a total of three times, finally getting pissed enough that she- but that is the film's best surprise.

Simon of the Desert is the third in a sequence of three films Buñuel made with Pinal and Brook (though he was only in small roles in the other two) and producer Gustavo Alatriste, Pinal's husband; the first two were Viridiana in 1961 and The Exterminating Angel in 1962. Taken together, they represent the most aggressive and anti-Catholic films of the director's career - Viridiana, famously, so wrathfully targets Church hierarchy and its relationship to temporal power structures that he got re-exiled from Franco's Spain after returning home for the first time in many years just to make it. The Exterminating Angel and Simon of the Desert found him back in Mexico, where he'd spent his entire post-war career, making the majority of the films he'd ever direct. Simon of the Desert was, in fact, his last Mexican film; the year prior, he made Diary of a Chambermaid in France, and it was to France he'd return to end his career on what is probably his best-known run of films.

Simon of the Desert is thus something of his farewell to the Mexican phase of his career, to black-and-white filmmaking, and to this spate of raging anti-Catholic, anti-Christian satires. For that's the glue unifying the Pinal-Alatriste-Brook films: all of them involve referencing and perverting traditional Christian iconography. This was hardly new territory for the director of the notorious L'âge d'or, but it's not really to be found much in his '40s and '50s Mexican films, certainly not to the extent of total warfare against Buñuel's Catholic upbringing, as we see in the '60s films (extending to the French The Milky Way, from 1969, but it feels of a different kind from the others - Pinal's absence is noted, as is the presence of color). Simon of the Desert is much less of a full-throated assault on norms and decency than its predecessors; it's clear even without the evidence of later interviews that Buñuel has a distinct admiration for Simon, or at least for his zealous commitment in the face of all rationality. The film is more than willing to let Simon's shabbier side get some sunlight; this is, after all, story that begins with what amounts to an army of groupies and the gift of a fancy new pillar - a strange sort of worldly possession, but a worldly possession all the same. It's still a satire against the hypocrisies of the Church, its relationship to the saints, and its love for fancy trappings while preaching the need to avoid giving into fleshy desires, and Simon is implicated in all that.

Even so, he's treated fairly by the film. Gabriel Figueroa's camera (this his last film with Buñuel after a substantial and successful collaboration) regards Brook's face with reserved awe. He's incorporated into the film's overall scheme of a wide range of greys and almost no hard blacks, creating a smeary space where the sky and the ground don't have a very clear distinction between them, giving the world more the feeling of a continuum that Brook's craggy faced is eased into, without being exaggerated to look grotesque in the way of such a large number of Buñuel characters. Pinal stands out more, creating a bit of a contrast, especially in her first and third appearance, either wearing black clothes, or riding in a black coffin that scuttles over the rocks like a lizard. And that contrast is confirmed by the way that Brook's solid performance clashes with Pinal's exaggerated, comically warped work as an oversexed little girl, an androgynous, Christlike shepherd, and finally an annoyed, angry brat.

The film is still willing to poke fun, in its extremely dry way, at the fundamental hypocritical conflict of Simon's character: he's extremely proud of how humble he is. But I can't shake the sense that Buñuel likes him - certainly more than the vulgarities of The Exterminating Angel! And for that reason, Simon of the Desert doesn't bite as hard, nor are its teeth so sharp, as the director's most aggressive films. It still has surrealist touches, mostly surrounding the Devil's changing outfits and ability to move impossibly thanks to the help of film editing, and the final sequence is a huge swerve into grimly hilarious absurdity, as Buñuel finds an unexpectedly hostile answer to the question of what a 5th Century ascetic would think Hell to be like. But its primary mode is much less one of extremes and exaggeration, than of a spare, clean style, anchored in those smooth greys. Helped, no doubt, by a short running time, the filmmakers are able to make the extremely small number of visual options (on the pillar looking down, below the pillar looking up, on the pillar looking out) feel varied enough that there are almost no obvious repeated shots, and the grey-on-grey aesthetic keeps feeling beautifully hazy, rather than drab.

The point being, there's a certain austerity to the film's aesthetic that sets it apart from all of the other late Buñuel that I've seen. Pauline Kael astutely pointed out that by emptying out the film of so much other than the essentials - sky, earth, the pillar, Brook, Pinal -Simon of the Desert amplifies the sense that it takes place in fable-time, and I can't think of a better way to look at it than that.

The fable-like mood, coupled with Buñuel's willingness to watch Simon rather than simply mock him, give this film's satire a noticeable different edge than the director's other '60s films. Those are all about the gleeful rage of a man who escaped, turning around to attack the forces he sees ruining the world with all the outrage he can muster. This is more warm and nostaglic in its rejection of Catholicism; the closest any of Buñuel's films come to match the irony of his famous sentiment "Thank God I'm an atheist". Yes, the Church is full of people who'd rather mindlessly praise saints than grapple with their own thoughts and behavior; yes, people who want to make a big show about being seen practicing humility and good works are hypocrites; yes, the Church is an ancient institution with no ability to function in the modern world, reacting with sullen annoyance that it can't go back to the 5th Century where everything made more sense (that's the most I have to say about the ending). But also, you can see why people still like to have it in their lives. This is still more satiric and mocking than otherwise - Buñuel isn't thinking about returning to the Church, or anything like that - but it's mockery that comes from something a bit closer to love than I'm used to from this director, and there's something unexpectedly pleasant about that.