I spy

In the annals of the great director/screenwriter collaborations, I don't know that Carol Reed and novelist Graham Greene get as much credit as they deserve; I don't know that they could get as much credit as they deserve. They worked together only three times, but the second of those resulted in one of the highest masterpieces of English-language cinema 1949's The Third Man, which was also the only original collaboration between them (it was preceded by a novella that was not meant to be published and existed only so Greene could work out the details). That was preceded by 1948's The Fallen Idol, adapted by Greene from his short story "The Basement Room", and if it's not quite as good as The Third Man, well how possibly could it be? But it's also a masterpiece or right next to it, one of the best films about children who don't understand the adult world and one of the best films about voyeurism.

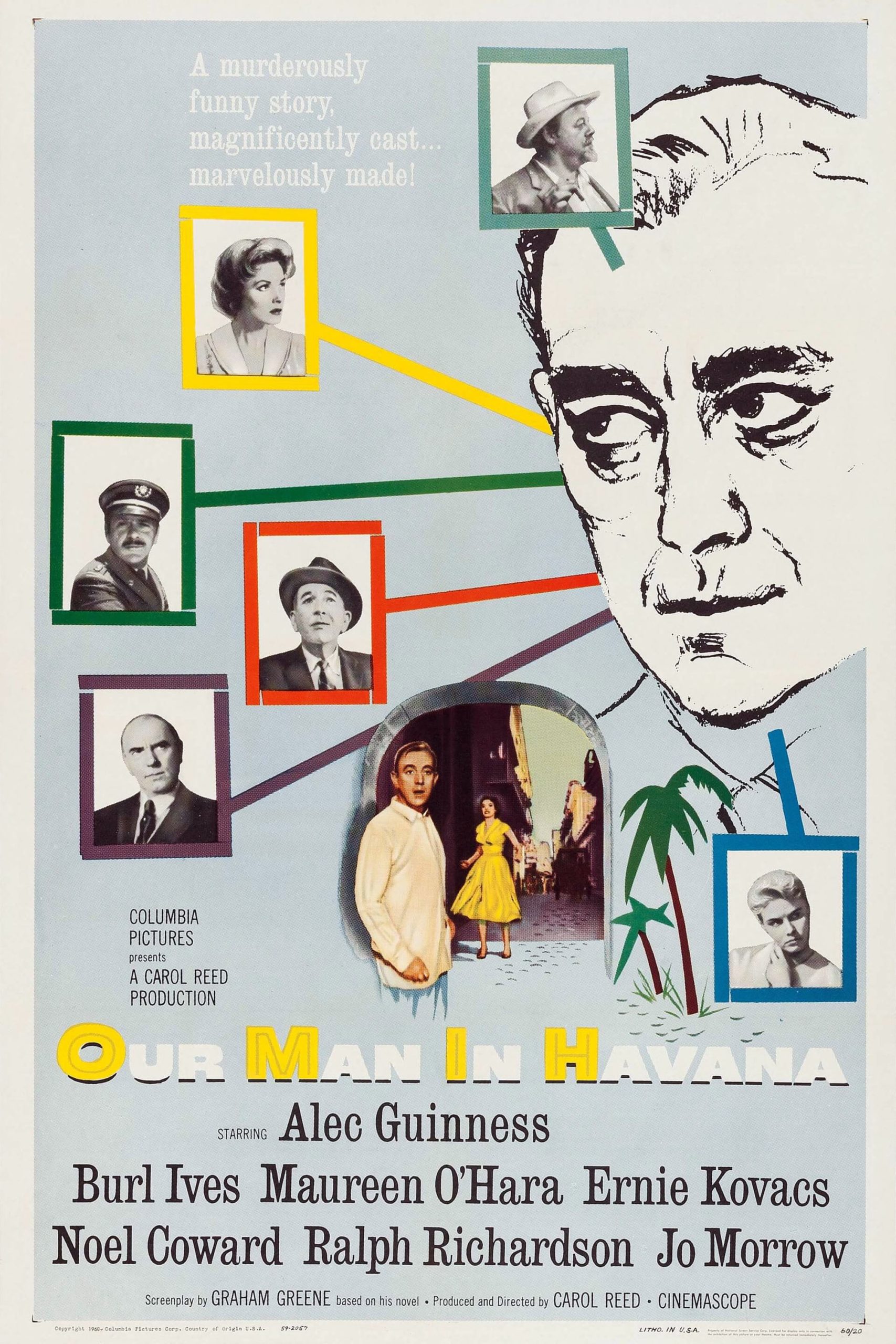

Ten years after The Third Man - a more productive decade for Greene (who released both The End of the Affair and The Quiet American in this time) than for Reed - they collaborated for the third and final time on a 1959 adaptation of Greene's 1958 novel Our Man in Havana. In both forms, this a sardonic, satiric takedown of Britain's intelligence agencies in the turbulence of pre-revolutionary Cuba (which, indeed, underwent its revolution after the publication of the book and before the production of the movie), rather nastily suggesting that Western spies are so up their own asses with bureaucracy and procedure that they're good for nothing at all but self-promotion and making things worse in the places they're allegedly "protecting". It parodied the '60s explosion of spy fiction in popular culture before it even existed, pointing out before the cinematic James Bond ever strapped on his Walter PPK that in reality, people like Bond are lazy careerists who are useless at best and dangeously useless at worst (this was five years after the first literary James Bond adventure, but the books' popularity was never as extreme as the movies'). Greene's acidic portrait of British intelligence beat John le Carré to the punch by three years (decades later, le Carré would write a virtual clone of the novel with 1996's The Tailor of Panama, itself made into a modestly enjoyable film), and mocked the United States' fumbling attempts to topple the Castro government before there was a Castro government in the first place.

It's a terrific yarn in any medium, but even as I acknowledge that the book is "better", my heart will always belong to the movie. For one thing, I saw it first. For another, the film is at least slightly funnier, thanks to the casting of Alec Guinness as the central character, a middle-class everyman-turned-socipathic cog in the MI6 machine. Few screen actors have ever been better than Guinness at exuding a mild, dry detachment from their surroundings, be it in comedies, dramas, or even lightsaber battles, and when that acting skill is pressed into service for an honest-to-God satire, it's basically the best possible marriage of performance and content. The basic plot material of Our Man in Havana goes to some pretty dark places, but one of the things that keeps the movie consistently... funny, I'd say, but it's an acerbic form of funny that's not to all tastes. One of the things that keeps it smirking, let's say, is that Guinness's understatement can't help but recast everything as mildly absurd, with him the one sane face making sense of it for us. The fact that he's a self-serving liar is, of course, part of the joke.

The third thing is that Reed was an extremely talented director and Oswald Morris was in the process of proving himself an extremely talented cinematographer, and Our Man in Havana looks great. It is, unabashedly, "The Third Man Lite", and not just in its visual aesthetic; the way the film uses music irresistible recalls the zither music of Anton Karas, discovered by Reed by accident in Vienna. Here, we get music that similarly seems to come onto the film right off the streets (not least because we often see the musicians strolling up and down, and bothering some of the characters), courtesy of Frank Deniz, a Welsh-born black man who'd spend much of his 20s and 30s traveling the eastern seaboard of the U.S. gaining an affection for Latin jazz, ultimately forming a band with his brothers Joe and Laurence. It's that band which provides the energetic soundtrack here.

But yes, it's mostly the visual aesthetic that I had in mind: Reed learned a lot of right things on the Third Man set, and he applies them in Our Man in Havana to terrific effect, introducing a degree of menace and danger into what could easily end up as little more than a zippy farce. Most overtly, the canted angles that he and Robert Krasker used so wantonly in the 1949 film have returned, though much reduced in frequency. In fact, the first canted angle straightens out over the course of a pan, and for a good long time we don't see another; if, in the earlier film, canted angles depicted an entire world gone off-balance, with everything falling down and going to hell, Our Man in Havana uses them in a much more targeted way, tilting the camera only as a sign that Jim Wormold - for that is the Guinness character's name - is descending into a world of spies and secret police deep enough that he can't control that world, or himself. Certainly, as the film progresses, and he becomes more fully implicated in the lies he's weaving, the film uses canted shots more and more, giving a sense of control being lost - and given the film's perspective on the back side of the revolution, it's not just Wormold who's losing that control.

It's probably about time to sketch out the plot. Wormold owns a vacuum shop in Havana - their big item, as seen in the store window looming in the foreground in an early shot (we notice the vacuum before we notice Wormold, which is surely no accident) is the "Atomic Pile", which snidely sums up the film's entire attitude towards the stuff of the late 1950s, when the Atomic Age has devolved from a civilisation-defining technical breakthrough to a branding gesture. He's a quiet nobody, enjoying the company of his German friend Dr. Hasselbacher (Burl Ives, whose attempt at a light German accent is adorably wobbly), and doting on his heavily Americanised daughter Milly (Jo Morrow), who has been lately receiving the affections of one Captain Segura (Ernie Kovacs), a notorious enforcer for the Batista government, and not remotely the kind of person a mild Englishman would like his daughter to be involved with. But Milly has been interested in a life beyond the means of a vacuum cleaner salesman, which makes Wormold very receptive when a man named Hawthorne (Noël Coward) comes along to first hint and then directly propose that Wormold might make a good secret agent - for Hawthorne is with MI6, building a Caribbean network, and he needs a man in Havana. Why in God's name he thinks Wormold is suited for the job is the first place where the film suggests that British Intelligence isn't living up to its name. At any rate, Wormold sucks horribly, and in order to keep Hawthorne from cutting him loose, he starts making up intelligence. Juicy intelligence, the kind that makes MI6 honcho "C" (Ralph Richardson) start salivating, and various enemy agents decide that Wormold is so good at uncovering secrets that even they didn't know about, he's certainly too dangerous to be left alive. For his part, Hawthorne almost immediately figures out that Wormold is full of it, but to reveal this to anybody would also reveal his own terrible judgment.

It's very impressive how Our Man in Havana has its cake and eats it too. One the one hand, this is all very goofy and Wormold is a pathetic, farcical character; on the other hand, people die, and it's his fault. Striking a balance where the film can remain playful while not diminishing the amorality of everybody involved - everybody, except for maybe Beatrice Severn (Maureen O'Hara), assigned as Wormold's secretary, who makes things much harder for him on account of trying to help him safeguard the lives of local assets who don't exist, and I'm not sure if that's just because O'Hara is so good at imbuing the character with unfussy sincerity - is chief among the film's achievements, and a perfect descendant of the bleak, "we're all going to hell, might as well laugh about it" attitude that Reed and Greene brought to The Third Man.

It's too sarcastic and cynical a film for its gravity to ever feel crushing, though the gravity remains: sarcasm and cynicism are themselves at least a bit heavy, after all. Plus, the film looks like a thriller, even as it acts like a comedy, which is a good way of approach thing weird tonal balance. Reed and Morris favor lots of high contrast lighting between the cool, shady interiors and sunny outdoors of Havana, where the film was shot with the support of the newly-installed Castro regime (Castro was, supposedly, disappointed that the end result wasn't more aggressively anti-Batista, but given how much vigor it pours into being anti-British, it's hard to know where that would have fit). The location photography is a huge boon for the film, which has a dense feeling of physical presence; it helps that the filmmakers have gone all-in on staging everything in depth, making the whole movie about the depths of rooms and the spaces between characters, the architecture of Havana and how people navigate it. The closeness of Wormold's rooms contrasted with the sprawl of the country club where he does his "spy work" is enough to tell a story about both this man's venality and the run-up to revolution all by itself.

At any rate, it's a lovely film to look at, staging its characters with the sinewy movements befitting a spy thriller and giving the whole thing a certain sense of pomposity that matches Wormold's increasingly smug vision of himself. It's certainly the least of the three Reed/Graham films - the story doesn't always have great momentum, and parts of the third quarter especially feel like they're being gotten through on the way to the delightful shrug of a final scene - but the mere fact that something this cleverly written and confidently stylish could be the "least" of anything speaks to how impressive and fruitful that partnership was.

Ten years after The Third Man - a more productive decade for Greene (who released both The End of the Affair and The Quiet American in this time) than for Reed - they collaborated for the third and final time on a 1959 adaptation of Greene's 1958 novel Our Man in Havana. In both forms, this a sardonic, satiric takedown of Britain's intelligence agencies in the turbulence of pre-revolutionary Cuba (which, indeed, underwent its revolution after the publication of the book and before the production of the movie), rather nastily suggesting that Western spies are so up their own asses with bureaucracy and procedure that they're good for nothing at all but self-promotion and making things worse in the places they're allegedly "protecting". It parodied the '60s explosion of spy fiction in popular culture before it even existed, pointing out before the cinematic James Bond ever strapped on his Walter PPK that in reality, people like Bond are lazy careerists who are useless at best and dangeously useless at worst (this was five years after the first literary James Bond adventure, but the books' popularity was never as extreme as the movies'). Greene's acidic portrait of British intelligence beat John le Carré to the punch by three years (decades later, le Carré would write a virtual clone of the novel with 1996's The Tailor of Panama, itself made into a modestly enjoyable film), and mocked the United States' fumbling attempts to topple the Castro government before there was a Castro government in the first place.

It's a terrific yarn in any medium, but even as I acknowledge that the book is "better", my heart will always belong to the movie. For one thing, I saw it first. For another, the film is at least slightly funnier, thanks to the casting of Alec Guinness as the central character, a middle-class everyman-turned-socipathic cog in the MI6 machine. Few screen actors have ever been better than Guinness at exuding a mild, dry detachment from their surroundings, be it in comedies, dramas, or even lightsaber battles, and when that acting skill is pressed into service for an honest-to-God satire, it's basically the best possible marriage of performance and content. The basic plot material of Our Man in Havana goes to some pretty dark places, but one of the things that keeps the movie consistently... funny, I'd say, but it's an acerbic form of funny that's not to all tastes. One of the things that keeps it smirking, let's say, is that Guinness's understatement can't help but recast everything as mildly absurd, with him the one sane face making sense of it for us. The fact that he's a self-serving liar is, of course, part of the joke.

The third thing is that Reed was an extremely talented director and Oswald Morris was in the process of proving himself an extremely talented cinematographer, and Our Man in Havana looks great. It is, unabashedly, "The Third Man Lite", and not just in its visual aesthetic; the way the film uses music irresistible recalls the zither music of Anton Karas, discovered by Reed by accident in Vienna. Here, we get music that similarly seems to come onto the film right off the streets (not least because we often see the musicians strolling up and down, and bothering some of the characters), courtesy of Frank Deniz, a Welsh-born black man who'd spend much of his 20s and 30s traveling the eastern seaboard of the U.S. gaining an affection for Latin jazz, ultimately forming a band with his brothers Joe and Laurence. It's that band which provides the energetic soundtrack here.

But yes, it's mostly the visual aesthetic that I had in mind: Reed learned a lot of right things on the Third Man set, and he applies them in Our Man in Havana to terrific effect, introducing a degree of menace and danger into what could easily end up as little more than a zippy farce. Most overtly, the canted angles that he and Robert Krasker used so wantonly in the 1949 film have returned, though much reduced in frequency. In fact, the first canted angle straightens out over the course of a pan, and for a good long time we don't see another; if, in the earlier film, canted angles depicted an entire world gone off-balance, with everything falling down and going to hell, Our Man in Havana uses them in a much more targeted way, tilting the camera only as a sign that Jim Wormold - for that is the Guinness character's name - is descending into a world of spies and secret police deep enough that he can't control that world, or himself. Certainly, as the film progresses, and he becomes more fully implicated in the lies he's weaving, the film uses canted shots more and more, giving a sense of control being lost - and given the film's perspective on the back side of the revolution, it's not just Wormold who's losing that control.

It's probably about time to sketch out the plot. Wormold owns a vacuum shop in Havana - their big item, as seen in the store window looming in the foreground in an early shot (we notice the vacuum before we notice Wormold, which is surely no accident) is the "Atomic Pile", which snidely sums up the film's entire attitude towards the stuff of the late 1950s, when the Atomic Age has devolved from a civilisation-defining technical breakthrough to a branding gesture. He's a quiet nobody, enjoying the company of his German friend Dr. Hasselbacher (Burl Ives, whose attempt at a light German accent is adorably wobbly), and doting on his heavily Americanised daughter Milly (Jo Morrow), who has been lately receiving the affections of one Captain Segura (Ernie Kovacs), a notorious enforcer for the Batista government, and not remotely the kind of person a mild Englishman would like his daughter to be involved with. But Milly has been interested in a life beyond the means of a vacuum cleaner salesman, which makes Wormold very receptive when a man named Hawthorne (Noël Coward) comes along to first hint and then directly propose that Wormold might make a good secret agent - for Hawthorne is with MI6, building a Caribbean network, and he needs a man in Havana. Why in God's name he thinks Wormold is suited for the job is the first place where the film suggests that British Intelligence isn't living up to its name. At any rate, Wormold sucks horribly, and in order to keep Hawthorne from cutting him loose, he starts making up intelligence. Juicy intelligence, the kind that makes MI6 honcho "C" (Ralph Richardson) start salivating, and various enemy agents decide that Wormold is so good at uncovering secrets that even they didn't know about, he's certainly too dangerous to be left alive. For his part, Hawthorne almost immediately figures out that Wormold is full of it, but to reveal this to anybody would also reveal his own terrible judgment.

It's very impressive how Our Man in Havana has its cake and eats it too. One the one hand, this is all very goofy and Wormold is a pathetic, farcical character; on the other hand, people die, and it's his fault. Striking a balance where the film can remain playful while not diminishing the amorality of everybody involved - everybody, except for maybe Beatrice Severn (Maureen O'Hara), assigned as Wormold's secretary, who makes things much harder for him on account of trying to help him safeguard the lives of local assets who don't exist, and I'm not sure if that's just because O'Hara is so good at imbuing the character with unfussy sincerity - is chief among the film's achievements, and a perfect descendant of the bleak, "we're all going to hell, might as well laugh about it" attitude that Reed and Greene brought to The Third Man.

It's too sarcastic and cynical a film for its gravity to ever feel crushing, though the gravity remains: sarcasm and cynicism are themselves at least a bit heavy, after all. Plus, the film looks like a thriller, even as it acts like a comedy, which is a good way of approach thing weird tonal balance. Reed and Morris favor lots of high contrast lighting between the cool, shady interiors and sunny outdoors of Havana, where the film was shot with the support of the newly-installed Castro regime (Castro was, supposedly, disappointed that the end result wasn't more aggressively anti-Batista, but given how much vigor it pours into being anti-British, it's hard to know where that would have fit). The location photography is a huge boon for the film, which has a dense feeling of physical presence; it helps that the filmmakers have gone all-in on staging everything in depth, making the whole movie about the depths of rooms and the spaces between characters, the architecture of Havana and how people navigate it. The closeness of Wormold's rooms contrasted with the sprawl of the country club where he does his "spy work" is enough to tell a story about both this man's venality and the run-up to revolution all by itself.

At any rate, it's a lovely film to look at, staging its characters with the sinewy movements befitting a spy thriller and giving the whole thing a certain sense of pomposity that matches Wormold's increasingly smug vision of himself. It's certainly the least of the three Reed/Graham films - the story doesn't always have great momentum, and parts of the third quarter especially feel like they're being gotten through on the way to the delightful shrug of a final scene - but the mere fact that something this cleverly written and confidently stylish could be the "least" of anything speaks to how impressive and fruitful that partnership was.