Woman with a whip

Barbara Stanwyck - the most sarcastic, mercilessly incisive leading lady of her generation, a biting sophisticate in the body of a tough dame. Samuel Fuller - the great journalist-director whose films have the precision and authenticity of a no-bullshit reporter, with the sensationalism of a man who knows the best way to get people to care about stories that matter is to lead with the blood and guts. Both of them excelled, at their peaks, in grubby, vulgar stories that would feel like exploitation potboilers if there wasn't so much furious human passion radiating out of them. They only worked together once, which isn't much of a surprise - their careers didn't overlap very much chronologically, and Stanwyck had moved away from grungier genres by the time Fuller came along - but something sounds so unbelievably right about putting those two names together that I'll permit myself to be disappointed by that fact anyway.

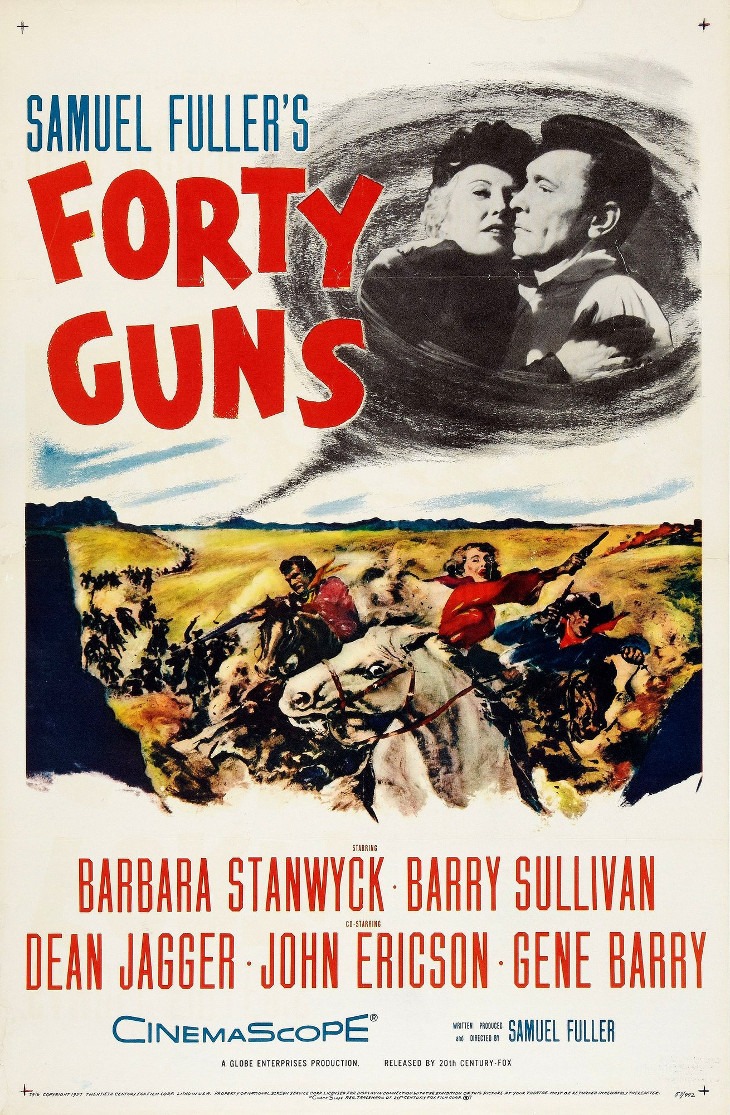

Happily, that one collaboration is absolutely terrific, more than justifying all my hopes for what a Fuller/Stanwyck picture might look like. And impressively, I'm not even sure that's the best part of Forty Guns, a 1957 Western that was Fuller's fourth and final entry in that genre. The film is a 20th Century Fox CinemaScope epic, sort of; nothing with a running time of 80 whole minutes can be called an "epic" with a straight face. On the other hand, no film that uses the punishingly wide aspect ratio of CinemaScope so robustly deserves to be called anything else. That format was four years old by the time Forty Guns hit theaters, and for the most part, it had caused filmmakers trouble more than it had done them any good: widescreen cinema of the mid and late '50s is full of uncertain compositions that stretch ensembles out in unnatural lines, and clutter up big empty sets with needless props and extras, just to make sure there's something to look at. And woe betide the actor who ends up in a CinemaScope single, lonely medium shots that leave the performer stranded in a great gulf of dead air.

Forty Guns, though, now there's a film that's using anamorphic widescreen like there'd never been any other option. Fuller and cinematographer Joseph Biroc (their third collaboration in a very productive 1957) are positively reckless in deciding where the place the camera relative to the action, including one of the boldest shots I've ever seen in a Western, pointing up and out from underneath a stagecoach, looking from below and behind at the horses hitched that coach rearing up in alarm. It's a stunning shot, part of an absolute barnburner of an opening scene that technically introduces us to the title characters, the forty men who ride in defense of Jessica Drummond (Stanwyck), the landowner who reigns over Cochise County, Arizona Territory, with a tyrannical fist, and she rides out at their head. But in the moment, it feels less like a group of people than a scourge of locusts sweeping down the hills to set upon a hapless mail coach, and the mood has an almost apocalyptic weight, between the striking angles (starting with a God's-eye view of the coach like a speck in the desert, before moving in closer to find different ways of looking at the action), the waves of dust clouds, and Harry Sukman's raging score.

In this, it does great work setting up a movie that sweeps through like a thunderstorm, wasting no time in pushing us through its story of violence and lawlessness. It's openly cribbing from the story of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone - it is, in fact, set in Tombstone - with the lawful Earp brothers replaced by the Bonnells: Griff (Barry Sullivan), a notorious gunslinger who has reformed and dedicated himself to upholding what exists of the law in Arizona, as well as Wes (Gene Barry) and Chico (Robert Dix). On the opposite side, rather than a handful of loosely-affiliated ne'er-do-wells is Jessica and her army, particularly her brother Brockie (John Ericson), who fully indulges his sister's power by running rampage throughout the county as it pleases him. Except it doesn't please Griff, whose first action upon arriving in Tombstone, basically, is to pistol-whip Brockie - taking care not to kill him, since Griff is savvy enough to know that upholding the law in Tombstone necessarily means working alongside Jessica. And this gets us to the real meat of the film, which is the erotic fascination that creeps in between the characters - calling it "love" is much too sentimental for a film that has zero patience for sentiment - despite the feeling of doom that hangs over the whole territory.

Stanwyck is expectedly great in playing a middle-aged woman whose openly fetishistic interest in power (the film even gives her a theme song, "Woman with a Whip", that's positively brazen in declaring this as a kink, for a '50s movie) has finally found a target worthy of her fascinations: in one especially sultry moment, she asks if she can feel Griff's pistol. Yes, "feel". "It might go off in your face", Griff replies smoothly. Pretty sure she likes it that way, Griff. Sullivan is pretty great himself; he's one of those troupers who shows up in everything and never makes an impression, but the way he allows himself to soften around Jessica without losing an ounce of his implacable morality - he's one of those "I killed a kid, and it's going to haunt me for the rest of my days" types - works extremely well, and he's entirely responsible for success of the film's climax, which is unfortunately less hard than Fuller wanted, and the studio-mandated adjustments feel tacked on and weirdly-staged. But in the actual moment, when Griff has to make his decision about when to fire a gun and at whom, Sullivan's mask-like emptying of any and all emotional affect is just amazing, a genuinely scary revelation of the depths of unfeeling steel that "good guy" in a bad world can adopt.

The toughness of the film, and its emphasis on violence as the only solution to the problems of the world, which is why the world is a shitty and broken place (there is no Western bravado here: the feeling that this necessarily must lead to a shootout is sickening, and the deaths all feel like gross wastes, even the deaths of designated villains) is perfect Fuller material, and in his hands, the Western backlot set feels just as slick with moral rot as the urban pits of one of his gangster movies. Which brings us back to the way he and Biroc present all of this, since as good as the acting is, as purposeful and devoid of bullshitting as the story is, Forty Guns is brilliant first and foremost because of how it looks. I never finished my thought, but this is easily the best use of CinemaScope I have seen in any '50s movie. And I haven't seen all of them, of course. But the expressive use that the filmmakers put it to here feels like a borderline experimental film, particularly when they give us an extreme close-up of eyes that more than fill the frame with terrible, cold resolve.

Even in less absurdly dramatic moments like that, the sense of immaculate control over the frame is simply off the charts: Fuller didn't invent staging a character in long shot over the shoulder of a character in medium close-up, but it looks fantastic here, creating one scene after another of different people trying to assert their control in the foreground while they are helplessly knocked down by the weight of what's going on in the background. The film transitions from quiet reverie to alert tension in ludicrous, wonderful long take that goes for minute after minute, sweeping us from a expansive shot of a room interior like a diorama to a claustrophobic attempt to look through a window and onwards. At one early point, apparently just showing off that they've solved a technology that was still giving everybody else problems, the filmmakers rack focus slightly, creating the weird warping effect typical of rack focus in CinemaScope, and rather than asking us to silently pretend we didn't notice it, as one does, the film exploits that warping, making it serve as a punctuation mark to the conversation in and of itself, beyond the shift in focus. Because if it's a world warped by violence, might as well give it warped images.

It's not just good for the '50s - any filmmaker in the 21st Century could stand to learn lesson from how this film activates the whole anamorphic frame, using it as a field of psychological warfare when it's not letting actual warfare, or the closest thing to, it, sprawl all across the oppressive width of the image. It's sophisticated, even elegant, while also being unyieldingly aggressive. And this is the Sam Fuller of it. Graceful and intelligent filmmaking that has been precisely designed to knock us on our asses, while presenting humans who feel both larger than life and uncomfortable real. Even by the standards of a great career, Forty Guns is a top-notch effort, one of the most psychosexually insightful Westerns I've seen as well as one of the leanest and and toughest.

Happily, that one collaboration is absolutely terrific, more than justifying all my hopes for what a Fuller/Stanwyck picture might look like. And impressively, I'm not even sure that's the best part of Forty Guns, a 1957 Western that was Fuller's fourth and final entry in that genre. The film is a 20th Century Fox CinemaScope epic, sort of; nothing with a running time of 80 whole minutes can be called an "epic" with a straight face. On the other hand, no film that uses the punishingly wide aspect ratio of CinemaScope so robustly deserves to be called anything else. That format was four years old by the time Forty Guns hit theaters, and for the most part, it had caused filmmakers trouble more than it had done them any good: widescreen cinema of the mid and late '50s is full of uncertain compositions that stretch ensembles out in unnatural lines, and clutter up big empty sets with needless props and extras, just to make sure there's something to look at. And woe betide the actor who ends up in a CinemaScope single, lonely medium shots that leave the performer stranded in a great gulf of dead air.

Forty Guns, though, now there's a film that's using anamorphic widescreen like there'd never been any other option. Fuller and cinematographer Joseph Biroc (their third collaboration in a very productive 1957) are positively reckless in deciding where the place the camera relative to the action, including one of the boldest shots I've ever seen in a Western, pointing up and out from underneath a stagecoach, looking from below and behind at the horses hitched that coach rearing up in alarm. It's a stunning shot, part of an absolute barnburner of an opening scene that technically introduces us to the title characters, the forty men who ride in defense of Jessica Drummond (Stanwyck), the landowner who reigns over Cochise County, Arizona Territory, with a tyrannical fist, and she rides out at their head. But in the moment, it feels less like a group of people than a scourge of locusts sweeping down the hills to set upon a hapless mail coach, and the mood has an almost apocalyptic weight, between the striking angles (starting with a God's-eye view of the coach like a speck in the desert, before moving in closer to find different ways of looking at the action), the waves of dust clouds, and Harry Sukman's raging score.

In this, it does great work setting up a movie that sweeps through like a thunderstorm, wasting no time in pushing us through its story of violence and lawlessness. It's openly cribbing from the story of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone - it is, in fact, set in Tombstone - with the lawful Earp brothers replaced by the Bonnells: Griff (Barry Sullivan), a notorious gunslinger who has reformed and dedicated himself to upholding what exists of the law in Arizona, as well as Wes (Gene Barry) and Chico (Robert Dix). On the opposite side, rather than a handful of loosely-affiliated ne'er-do-wells is Jessica and her army, particularly her brother Brockie (John Ericson), who fully indulges his sister's power by running rampage throughout the county as it pleases him. Except it doesn't please Griff, whose first action upon arriving in Tombstone, basically, is to pistol-whip Brockie - taking care not to kill him, since Griff is savvy enough to know that upholding the law in Tombstone necessarily means working alongside Jessica. And this gets us to the real meat of the film, which is the erotic fascination that creeps in between the characters - calling it "love" is much too sentimental for a film that has zero patience for sentiment - despite the feeling of doom that hangs over the whole territory.

Stanwyck is expectedly great in playing a middle-aged woman whose openly fetishistic interest in power (the film even gives her a theme song, "Woman with a Whip", that's positively brazen in declaring this as a kink, for a '50s movie) has finally found a target worthy of her fascinations: in one especially sultry moment, she asks if she can feel Griff's pistol. Yes, "feel". "It might go off in your face", Griff replies smoothly. Pretty sure she likes it that way, Griff. Sullivan is pretty great himself; he's one of those troupers who shows up in everything and never makes an impression, but the way he allows himself to soften around Jessica without losing an ounce of his implacable morality - he's one of those "I killed a kid, and it's going to haunt me for the rest of my days" types - works extremely well, and he's entirely responsible for success of the film's climax, which is unfortunately less hard than Fuller wanted, and the studio-mandated adjustments feel tacked on and weirdly-staged. But in the actual moment, when Griff has to make his decision about when to fire a gun and at whom, Sullivan's mask-like emptying of any and all emotional affect is just amazing, a genuinely scary revelation of the depths of unfeeling steel that "good guy" in a bad world can adopt.

The toughness of the film, and its emphasis on violence as the only solution to the problems of the world, which is why the world is a shitty and broken place (there is no Western bravado here: the feeling that this necessarily must lead to a shootout is sickening, and the deaths all feel like gross wastes, even the deaths of designated villains) is perfect Fuller material, and in his hands, the Western backlot set feels just as slick with moral rot as the urban pits of one of his gangster movies. Which brings us back to the way he and Biroc present all of this, since as good as the acting is, as purposeful and devoid of bullshitting as the story is, Forty Guns is brilliant first and foremost because of how it looks. I never finished my thought, but this is easily the best use of CinemaScope I have seen in any '50s movie. And I haven't seen all of them, of course. But the expressive use that the filmmakers put it to here feels like a borderline experimental film, particularly when they give us an extreme close-up of eyes that more than fill the frame with terrible, cold resolve.

Even in less absurdly dramatic moments like that, the sense of immaculate control over the frame is simply off the charts: Fuller didn't invent staging a character in long shot over the shoulder of a character in medium close-up, but it looks fantastic here, creating one scene after another of different people trying to assert their control in the foreground while they are helplessly knocked down by the weight of what's going on in the background. The film transitions from quiet reverie to alert tension in ludicrous, wonderful long take that goes for minute after minute, sweeping us from a expansive shot of a room interior like a diorama to a claustrophobic attempt to look through a window and onwards. At one early point, apparently just showing off that they've solved a technology that was still giving everybody else problems, the filmmakers rack focus slightly, creating the weird warping effect typical of rack focus in CinemaScope, and rather than asking us to silently pretend we didn't notice it, as one does, the film exploits that warping, making it serve as a punctuation mark to the conversation in and of itself, beyond the shift in focus. Because if it's a world warped by violence, might as well give it warped images.

It's not just good for the '50s - any filmmaker in the 21st Century could stand to learn lesson from how this film activates the whole anamorphic frame, using it as a field of psychological warfare when it's not letting actual warfare, or the closest thing to, it, sprawl all across the oppressive width of the image. It's sophisticated, even elegant, while also being unyieldingly aggressive. And this is the Sam Fuller of it. Graceful and intelligent filmmaking that has been precisely designed to knock us on our asses, while presenting humans who feel both larger than life and uncomfortable real. Even by the standards of a great career, Forty Guns is a top-notch effort, one of the most psychosexually insightful Westerns I've seen as well as one of the leanest and and toughest.