The truth changes color, depending on the light

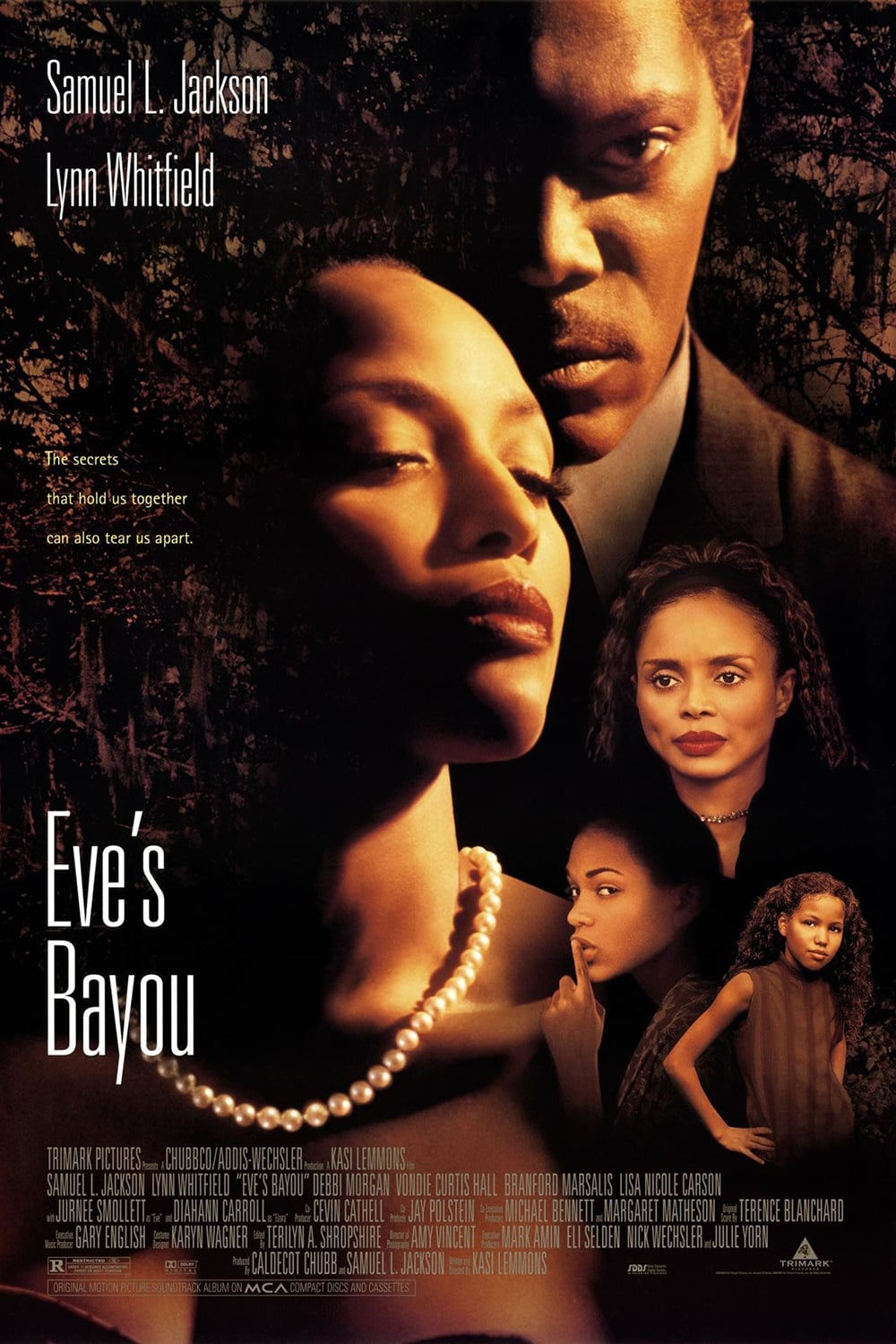

There are some movies that deserve to be better-known, but one can understand why they aren't: lack of home video availability, they're too old, they're too difficult, they're too small, and plenty of other reasons. This is not the case with Eve's Bayou, Kasi Lemmons's 1997 directing and screenwriting debut. There are, of course, some easy and at least partially accurate explanations (the obvious one is that movies with all African-American casts historically underperform at the box office), but on the other hand, if I were to say that there's a film starring Samuel L. Jackson (in one of the best performances of his career, no less), that Roger Ebert declared at the time to be the best film of its year, surely you'd suppose it would have some level of ongoing visibility. If that has been the case with this particular film, I have not seen it.

A pity, because it's pretty great. I can't bring myself to co-sign Ebert's level of enthusiasm: the film has some distinct rough bits. The roughest probably being an inexplicably misjudged score by Terence Blanchard, who certainly is capable of better than this, and has proved it several times over in his many wonderful collaborations with director Spike Lee. I note that one of the other times I have flat-out disliked a Blanchard score was in the Lemmons-directed Harriet from 2019, so perhaps it's just an unfortunate pairing of artistic sensibilities. At any rate, back in 1997, Blanchard provided Eve's Bayou with a genuinely inexplicable hodge-podge of musical tonalities, varied enough that sometimes, as chance would have it, things land perfectly, and the film's otherwordly mixture of memory and physical presence are met with an appropriately dreamy, mystical snatch of music; or perhaps there's a bit of lightly menacing jazz to evoke the Louisiana Voodoo culture purring beneath so much of the plot. But more often, it's something bouncy and energetic when the film should be building up momentum for its fatalistic ending, or something slinky and humid when it's trying to be pensive in its childlike innocence. It's so exceptionally bad that I'm sure there must have been come cunning reason for it all, but damn me if I can spot what that would be.

Thankfully, the music is literally the only actual problem I can point to in Eve's Bayou, a movie that otherwise stands as an especially proud example of the kind of challenging, multi-layered storytelling that indie filmmakers of this period were always striving for, and sometimes even hit. The film doesn't hide its intentions: the very first sentence of voiceover narration (delivered by Tamara Tunie) offers some musings on the elusive nature of memory, and the second sentence situates this in "the summer I killed my father". So there won't be much in the way of surprises later on.

We get a bit more after that, learning that the town where this all takes place is called Eve's Bayou, named for Eve Batiste, the slave woman who saved the life of General Jean-Paul Batiste and received her freedom in return, before birthing a dynasty that would continue into the 20th Century; in fact, our ten-year-old protagonist is herself an Eve Batiste (Jurnee Smollett), and this is where things start to get interesting. Titles of movies matter, and calling this one Eve's Bayou draws attention to the town, and to its legacy, but it also evokes a childhood adventure story. That is, there's Eve's Bayou, a municipality, but there's also Eve's bayou, the swampy land where our little Eve wanders around over the course of this very eventful summer in the early 1960s. And that muddying of the two meanings of the title, and the two different Eves they could refer to, already does quite a bit to suggest how the film is going to play around with the interaction of Then and Now. This is a film where the past is very urgently trying to make itself known, and a film about the malleability of memory, which makes it so very hard to be certain what the past actually was. We're still all of about 20 seconds into it, by the way.

The film ends up being less about "our" Eve and more about the Batiste family in general: father Louis (Jackson) is a doctor and a highly respected member of the community, part of the emerging Black upper middle class in the middle of the 20th Century; he's also having an affair, possibly several of them. And this is something that his wife Roz (Lynn Whitfield) is just barely starting to notice, putting a pressure on the family. It's not the only one: Eve is having what can only be called visions, shown to us as fragments of grainy, high-contrast black and white, and Louis's thrice-widowed sister Mozelle (Debbi Morgan) notices this, as part of the family's legacy of psychic power. And both Eve and Mozelle are starting to pick up vague intimations that something bad is in the offing, which Roz learns about from a much surlier and even cruel psychic, the fortune teller and swamp witch Elzora (Diahann Carroll); she suggests Roz be mindful of her children, which the mother takes as a sign to keep Eve, 14-year-old Cisely (Meagan Good), and nine-year-old Poe (Jake Smollett) under lock and key. Which proves to be an unendurable punishment for Cisely, just entering puberty, and growing extremely hostile to her mother in a rather directed but seemingly unmotivated way.

That's a lot of stuff to fill a potboiler, but Lemmons never treats this like that. This is a film about personalities in conflict, not about melodramatic struggling, and even as the Batiste family skeletons grow increasingly troublesome, Eve's Bayou is never trying to be a cheap shocker. Its twists are motivated by the gradual development of its theme of memory and buried trauma coming along to color the present, and they feel both natural and sad, rather than astonishing and sordid. Having already presented the film as a memory, and having already started to focus on the inherent slipperiness and incompleteness of memory, Lemmons is able to give the whole thing a rich, dreamy feeling. It's a rich and precise world - the visual design of the Batiste home and the surrounding bayou are wonderfully particular without calling attention to themselves - but the story itself seems to be fragmentary and elliptical. And this is very much how we remember childhood, is it not? The stable places emerge fully-formed, with events flickering uncertainly across them. Eve's Bayou isn't a story about remembering childhood, accurately or otherwise, but it is a film about subjectivity, and subtly but insistently reminding us of that subjectivity in the film's very narrative framework is an elegant way to keep that theme at the fore.

Not that the film needs help. Eve's Bayou is constantly playing with the blurry line between the past as memory and the present, sometimes in some very blunt ways, as when Mozelle is so carried away with a story she's telling that she simple walks into the the scene from her own past, narrating it to Eve even as she re-enacts the event. The script keeps returning to things that happened, things that are suspected to have happened, things that are remembered in different ways; it's all very hazy and almost fantastical, a mood sharpened by the repeated mentions of second sight and folk magic. It's to the great credit of the cast that they're able to pick up this mood and run with it, especially Morgan, who is the focal point of much of the film's most atmospheric moments, while also managing to make Mozelle an intelligible person, resourceful and smart and strategic, yearning and sad, snappish and businesslike. Really, there are no weak performances here (though the kids are, as one might expect, generally less consistent than the adults), with everybody giving just the right amount of stylisation to keep the slightly ghostly mood alive.

It's a really extraordinary mood piece that's also a piercing, challenging, and tenderly sad character study - from that first line, this is basically a tragedy about Eve's decision to kill her father, and the film treats this as a kind of regrettable, mordant coming-of-age story rather than a thriller or any such thing - and a lovely sketch of a very distinct community and culture. It has a rich enough sense of place to survive some generically flat cinematography; it has a weird kind of editing that's both tightly paced and enjoyably shaggy, letting us peer into corners and hang out with interesting characters in an unhurried, even as the thing feels like it's constantly pick up speed. All told, it's remarkably controlled, a bold debut that maneuvers through story twists and tonal shifts smoothly if not always invisibly. Lemmons has not yet come close to matching this achievement, though her subsequent films are all at least interesting in their different ways; but if this always remains her artistic peak, it's quite an achievement - bold and inventive even by the standards of a very bold and inventive mode of filmmaking.

A pity, because it's pretty great. I can't bring myself to co-sign Ebert's level of enthusiasm: the film has some distinct rough bits. The roughest probably being an inexplicably misjudged score by Terence Blanchard, who certainly is capable of better than this, and has proved it several times over in his many wonderful collaborations with director Spike Lee. I note that one of the other times I have flat-out disliked a Blanchard score was in the Lemmons-directed Harriet from 2019, so perhaps it's just an unfortunate pairing of artistic sensibilities. At any rate, back in 1997, Blanchard provided Eve's Bayou with a genuinely inexplicable hodge-podge of musical tonalities, varied enough that sometimes, as chance would have it, things land perfectly, and the film's otherwordly mixture of memory and physical presence are met with an appropriately dreamy, mystical snatch of music; or perhaps there's a bit of lightly menacing jazz to evoke the Louisiana Voodoo culture purring beneath so much of the plot. But more often, it's something bouncy and energetic when the film should be building up momentum for its fatalistic ending, or something slinky and humid when it's trying to be pensive in its childlike innocence. It's so exceptionally bad that I'm sure there must have been come cunning reason for it all, but damn me if I can spot what that would be.

Thankfully, the music is literally the only actual problem I can point to in Eve's Bayou, a movie that otherwise stands as an especially proud example of the kind of challenging, multi-layered storytelling that indie filmmakers of this period were always striving for, and sometimes even hit. The film doesn't hide its intentions: the very first sentence of voiceover narration (delivered by Tamara Tunie) offers some musings on the elusive nature of memory, and the second sentence situates this in "the summer I killed my father". So there won't be much in the way of surprises later on.

We get a bit more after that, learning that the town where this all takes place is called Eve's Bayou, named for Eve Batiste, the slave woman who saved the life of General Jean-Paul Batiste and received her freedom in return, before birthing a dynasty that would continue into the 20th Century; in fact, our ten-year-old protagonist is herself an Eve Batiste (Jurnee Smollett), and this is where things start to get interesting. Titles of movies matter, and calling this one Eve's Bayou draws attention to the town, and to its legacy, but it also evokes a childhood adventure story. That is, there's Eve's Bayou, a municipality, but there's also Eve's bayou, the swampy land where our little Eve wanders around over the course of this very eventful summer in the early 1960s. And that muddying of the two meanings of the title, and the two different Eves they could refer to, already does quite a bit to suggest how the film is going to play around with the interaction of Then and Now. This is a film where the past is very urgently trying to make itself known, and a film about the malleability of memory, which makes it so very hard to be certain what the past actually was. We're still all of about 20 seconds into it, by the way.

The film ends up being less about "our" Eve and more about the Batiste family in general: father Louis (Jackson) is a doctor and a highly respected member of the community, part of the emerging Black upper middle class in the middle of the 20th Century; he's also having an affair, possibly several of them. And this is something that his wife Roz (Lynn Whitfield) is just barely starting to notice, putting a pressure on the family. It's not the only one: Eve is having what can only be called visions, shown to us as fragments of grainy, high-contrast black and white, and Louis's thrice-widowed sister Mozelle (Debbi Morgan) notices this, as part of the family's legacy of psychic power. And both Eve and Mozelle are starting to pick up vague intimations that something bad is in the offing, which Roz learns about from a much surlier and even cruel psychic, the fortune teller and swamp witch Elzora (Diahann Carroll); she suggests Roz be mindful of her children, which the mother takes as a sign to keep Eve, 14-year-old Cisely (Meagan Good), and nine-year-old Poe (Jake Smollett) under lock and key. Which proves to be an unendurable punishment for Cisely, just entering puberty, and growing extremely hostile to her mother in a rather directed but seemingly unmotivated way.

That's a lot of stuff to fill a potboiler, but Lemmons never treats this like that. This is a film about personalities in conflict, not about melodramatic struggling, and even as the Batiste family skeletons grow increasingly troublesome, Eve's Bayou is never trying to be a cheap shocker. Its twists are motivated by the gradual development of its theme of memory and buried trauma coming along to color the present, and they feel both natural and sad, rather than astonishing and sordid. Having already presented the film as a memory, and having already started to focus on the inherent slipperiness and incompleteness of memory, Lemmons is able to give the whole thing a rich, dreamy feeling. It's a rich and precise world - the visual design of the Batiste home and the surrounding bayou are wonderfully particular without calling attention to themselves - but the story itself seems to be fragmentary and elliptical. And this is very much how we remember childhood, is it not? The stable places emerge fully-formed, with events flickering uncertainly across them. Eve's Bayou isn't a story about remembering childhood, accurately or otherwise, but it is a film about subjectivity, and subtly but insistently reminding us of that subjectivity in the film's very narrative framework is an elegant way to keep that theme at the fore.

Not that the film needs help. Eve's Bayou is constantly playing with the blurry line between the past as memory and the present, sometimes in some very blunt ways, as when Mozelle is so carried away with a story she's telling that she simple walks into the the scene from her own past, narrating it to Eve even as she re-enacts the event. The script keeps returning to things that happened, things that are suspected to have happened, things that are remembered in different ways; it's all very hazy and almost fantastical, a mood sharpened by the repeated mentions of second sight and folk magic. It's to the great credit of the cast that they're able to pick up this mood and run with it, especially Morgan, who is the focal point of much of the film's most atmospheric moments, while also managing to make Mozelle an intelligible person, resourceful and smart and strategic, yearning and sad, snappish and businesslike. Really, there are no weak performances here (though the kids are, as one might expect, generally less consistent than the adults), with everybody giving just the right amount of stylisation to keep the slightly ghostly mood alive.

It's a really extraordinary mood piece that's also a piercing, challenging, and tenderly sad character study - from that first line, this is basically a tragedy about Eve's decision to kill her father, and the film treats this as a kind of regrettable, mordant coming-of-age story rather than a thriller or any such thing - and a lovely sketch of a very distinct community and culture. It has a rich enough sense of place to survive some generically flat cinematography; it has a weird kind of editing that's both tightly paced and enjoyably shaggy, letting us peer into corners and hang out with interesting characters in an unhurried, even as the thing feels like it's constantly pick up speed. All told, it's remarkably controlled, a bold debut that maneuvers through story twists and tonal shifts smoothly if not always invisibly. Lemmons has not yet come close to matching this achievement, though her subsequent films are all at least interesting in their different ways; but if this always remains her artistic peak, it's quite an achievement - bold and inventive even by the standards of a very bold and inventive mode of filmmaking.