On the hunt

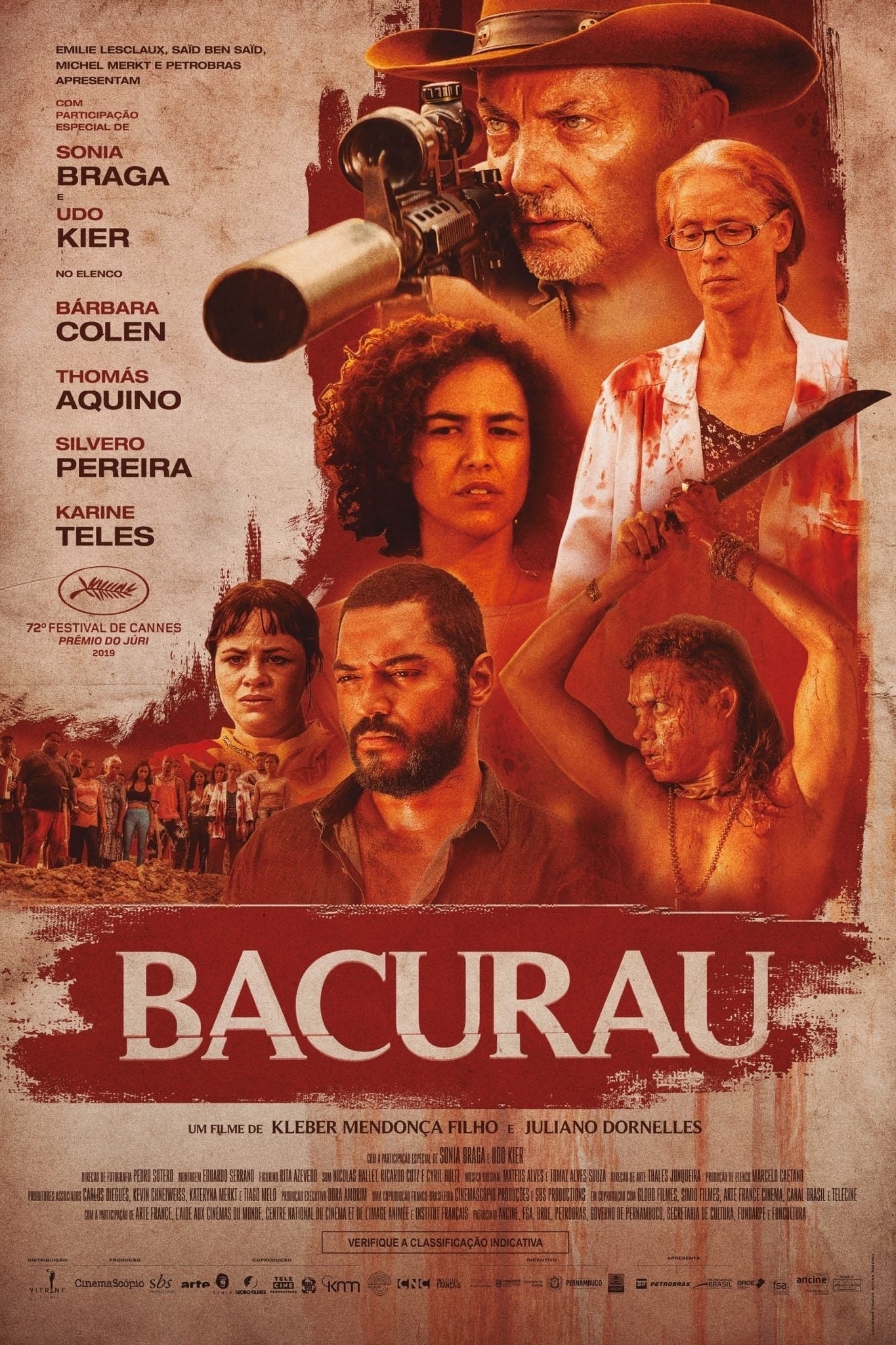

One thing that nobody can take away from Bacurau, the third feature directed by Brazilian art house favorite Kleber Mendonça Filho (co-directing here alongside his former production designer Juliano Dornelles): it's unpredictable. The film wear so many hats over the course of its 131 minutes, sometimes wearing them on top of each other, that it's barely possible to even describe it in terms of something so simple as what genre it belongs to. It is, in no particular order, a science-fiction art house action thriller exploitation satire about the gently undulating rhythms of a beatifically welcoming small town in the rural northwest of Brazil with strong anti-colonialist tendencies. I will assume at least a couple of words in that sentence appeal to you, because I'm honestly not entirely sure what's left if they didn't.

The film, which tied for the Jury Prize at the 2019 Cannes International Film Festival (it shared the award with the considerably less interesting Les Misérables), broadly breaks into two parts, though those two parts are awfully permeable. In the beginning, it is a dreamy, quasi-mystical slice-of-life story of the people in Bacurau, a small town that has gathered to mourn the death of its oldest resident, 94-year-old Carmelita (Lia de Itamaracá). In the second, it's a gory-soaked shoot-'em-up in which well-armed white Americans lay siege to the town like bandits in a spaghetti Western, while the locals hole themselves up and struggle to find a way to fight back. The transition between these two things happens with surprising elegance.

This is because, more than it's anything else, Bacurau is a gloriously warped compendium of striking moments, ranging from solemn art cinema realism of the most sedate kind to sequences so pointedly gauzy and surreal that it's hard to say if we're watching a dream sequence or not. It begins somewhere in the middle of those extremes, with a woman, Teresa (Bárbara Colen) being jolted awake as the truck she's riding in drives over an empty coffin in the middle of the isolated country road. As she looks ahead, it turns out there are several other coffins, which seem to have been dropped out of a coffin truck that's having trouble down the road a bit. If that sounds like more metaphor than any one movie should be able to cope with, rest assured, it amazingly doesn't play that way. Oh, it gets us thinking about death immediately, but there's no emphasis on it, no moment where we're invited to think about the memento mori strewn all across Teresa's path; it's folded into the natural development of the scene. It is, indeed, a perfect combination of low-key realism and surrealism, and that, far more than the coffins, is what actually sets us up for the rest of the movie.

Initially, at least, the low-key realism looks like it's going to take the lead. Teresa is returning to Bacurau, her hometown, but she's not really there to be our entry in to the world. In fact, once we get to Bacurau, she ends up serving as a familiar face to anchor ourselves, rather than a clearly-defined character. Indeed, none of the Bacurau residents really emerge as having specific personalities, except for the antagonistic, sharp-tongued Domingas (played by Sonia Braga, one of the two most recognisable faces in the cast, and this is presumably not a coincidence), which I think we can generously assume to be part of the film's deliberate strategy. The filmmakers present the small town as a kind of communitarian paradise, where everybody is free to live their best life and share the burden of keeping everyone else safe and happy. It's a space devoid or judgment, a pansexual, panracial state of bliss. Describing it like that surely makes it sound more wobbly than it is in practice; in fact, the way the film presents it is the most solid, square realism in the whole production. Stylistically, this is almost purposefully generic, the kind of standard art house, festival circuit filmmaking that's been a reliable brand of filmmaking for decades at this point.

This isn't laziness, though I was tempted to wonder about that at first; rather, it's how the film builds its foundation. Everything else we'll encounter in the movie is a disruption to the normal flow of life in Bacurau, and a big part of how the filmmakers show this is simply by completely changing their style as needed. We see this first, and most gently, during Carmelita's funeral, which begins with the townspeople taking what seems to be some kind of locally-grown psychedelic plant material. What follows is not a trite "head trip" sequence, thankfully, but it's motivated by that; the film starts to use cross dissolves to go along with its dreamy, ritualistic music, in creating a sequence that suggests the characters have been removed from their bodies, combined into a sort of collective mourning identity. It's really just an extension of the communitarian vibe from earlier, but communicated through surrealism rather than realism.

It's after this event, that the plot actually begins: Bacurau disappears from Google maps, and all trace of the town is apparently wiped off the internet. Given the film's commitment to slowly letting its plot develop, it's no shock that this is treated as a curiosity rather than a crisis, but we start to learn more than the townspeople shortly thereafter, and we can suppose this is related to the appearance of some gun-toting "Americans", though there's a pointedly international feel to the actors chosen, not least because they're being led by Udo Kier. As we learn in a very talky, over-written scene that's far and away the worst part of the film (honestly, every time the Americans are left to chat and deliver exposition, the film's momentum breaks pretty badly), they're here to do some human hunting, and the extraordinarily kind and harmless people of Bacurau are the perfect targets. But we're not even halfway through the movie yet, so clearly it's going to be a bit more complicated than that.

As metaphors go, they don't get much more obvious (a fact attested to by the existence of the American The Hunt, which uses the exact same metaphor for very different thematic ends), but Bacurau never claims otherwise; in keeping with its overall two-part split, one might even go so far as to say that the break between the subtle ways that the film develops its portrait of the community and the screeching loudness with which it portrays the violent, exploitative Americans is itself meant to tell us how to react to those two groups. Hell, if the film can completely change genres to foreground the difference between the two, it can surely also switch up its rhetorical strategies. And change genres it does, become an impressively gory action film, albeit one that can revert back to its more thoughtful reveries on a moment's notice, if it needs to. It's an impressive game that Mendonça Filho and Dornelles are playing, even if they don't necessarily always play it perfectly (the film makes us wait for the ending long after it's clear what the ending is going to be, so the run-up to the big showdown feels a bit draggy, but not in the deliberate slow-cinema manner of the opening), and the fact that Bacurau is so willing to combine so many flavors of movie into one package, damn the consequences, instantly endears it to me. It's sloppy and grand, the kind of movie that's so big in every way that it's hard not to be sucked in by its gravitation field, no matter how much this or that scene is imperfect, this or that character underdeveloped, or what have you.

The film, which tied for the Jury Prize at the 2019 Cannes International Film Festival (it shared the award with the considerably less interesting Les Misérables), broadly breaks into two parts, though those two parts are awfully permeable. In the beginning, it is a dreamy, quasi-mystical slice-of-life story of the people in Bacurau, a small town that has gathered to mourn the death of its oldest resident, 94-year-old Carmelita (Lia de Itamaracá). In the second, it's a gory-soaked shoot-'em-up in which well-armed white Americans lay siege to the town like bandits in a spaghetti Western, while the locals hole themselves up and struggle to find a way to fight back. The transition between these two things happens with surprising elegance.

This is because, more than it's anything else, Bacurau is a gloriously warped compendium of striking moments, ranging from solemn art cinema realism of the most sedate kind to sequences so pointedly gauzy and surreal that it's hard to say if we're watching a dream sequence or not. It begins somewhere in the middle of those extremes, with a woman, Teresa (Bárbara Colen) being jolted awake as the truck she's riding in drives over an empty coffin in the middle of the isolated country road. As she looks ahead, it turns out there are several other coffins, which seem to have been dropped out of a coffin truck that's having trouble down the road a bit. If that sounds like more metaphor than any one movie should be able to cope with, rest assured, it amazingly doesn't play that way. Oh, it gets us thinking about death immediately, but there's no emphasis on it, no moment where we're invited to think about the memento mori strewn all across Teresa's path; it's folded into the natural development of the scene. It is, indeed, a perfect combination of low-key realism and surrealism, and that, far more than the coffins, is what actually sets us up for the rest of the movie.

Initially, at least, the low-key realism looks like it's going to take the lead. Teresa is returning to Bacurau, her hometown, but she's not really there to be our entry in to the world. In fact, once we get to Bacurau, she ends up serving as a familiar face to anchor ourselves, rather than a clearly-defined character. Indeed, none of the Bacurau residents really emerge as having specific personalities, except for the antagonistic, sharp-tongued Domingas (played by Sonia Braga, one of the two most recognisable faces in the cast, and this is presumably not a coincidence), which I think we can generously assume to be part of the film's deliberate strategy. The filmmakers present the small town as a kind of communitarian paradise, where everybody is free to live their best life and share the burden of keeping everyone else safe and happy. It's a space devoid or judgment, a pansexual, panracial state of bliss. Describing it like that surely makes it sound more wobbly than it is in practice; in fact, the way the film presents it is the most solid, square realism in the whole production. Stylistically, this is almost purposefully generic, the kind of standard art house, festival circuit filmmaking that's been a reliable brand of filmmaking for decades at this point.

This isn't laziness, though I was tempted to wonder about that at first; rather, it's how the film builds its foundation. Everything else we'll encounter in the movie is a disruption to the normal flow of life in Bacurau, and a big part of how the filmmakers show this is simply by completely changing their style as needed. We see this first, and most gently, during Carmelita's funeral, which begins with the townspeople taking what seems to be some kind of locally-grown psychedelic plant material. What follows is not a trite "head trip" sequence, thankfully, but it's motivated by that; the film starts to use cross dissolves to go along with its dreamy, ritualistic music, in creating a sequence that suggests the characters have been removed from their bodies, combined into a sort of collective mourning identity. It's really just an extension of the communitarian vibe from earlier, but communicated through surrealism rather than realism.

It's after this event, that the plot actually begins: Bacurau disappears from Google maps, and all trace of the town is apparently wiped off the internet. Given the film's commitment to slowly letting its plot develop, it's no shock that this is treated as a curiosity rather than a crisis, but we start to learn more than the townspeople shortly thereafter, and we can suppose this is related to the appearance of some gun-toting "Americans", though there's a pointedly international feel to the actors chosen, not least because they're being led by Udo Kier. As we learn in a very talky, over-written scene that's far and away the worst part of the film (honestly, every time the Americans are left to chat and deliver exposition, the film's momentum breaks pretty badly), they're here to do some human hunting, and the extraordinarily kind and harmless people of Bacurau are the perfect targets. But we're not even halfway through the movie yet, so clearly it's going to be a bit more complicated than that.

As metaphors go, they don't get much more obvious (a fact attested to by the existence of the American The Hunt, which uses the exact same metaphor for very different thematic ends), but Bacurau never claims otherwise; in keeping with its overall two-part split, one might even go so far as to say that the break between the subtle ways that the film develops its portrait of the community and the screeching loudness with which it portrays the violent, exploitative Americans is itself meant to tell us how to react to those two groups. Hell, if the film can completely change genres to foreground the difference between the two, it can surely also switch up its rhetorical strategies. And change genres it does, become an impressively gory action film, albeit one that can revert back to its more thoughtful reveries on a moment's notice, if it needs to. It's an impressive game that Mendonça Filho and Dornelles are playing, even if they don't necessarily always play it perfectly (the film makes us wait for the ending long after it's clear what the ending is going to be, so the run-up to the big showdown feels a bit draggy, but not in the deliberate slow-cinema manner of the opening), and the fact that Bacurau is so willing to combine so many flavors of movie into one package, damn the consequences, instantly endears it to me. It's sloppy and grand, the kind of movie that's so big in every way that it's hard not to be sucked in by its gravitation field, no matter how much this or that scene is imperfect, this or that character underdeveloped, or what have you.