Who let the dog out?

The oldest film of which I am personally aware that features the scripted antics of a stunt dog is the Edison Manufacturing Company's The Whole Dam Family and the Dam Dog, which came out in 1905. So, like, they've had a while to figure this out. And I think I am not making a controversial claim if I suggest that, in the intervening 115 years, there have been some fine films featuring dogs, some of them cunningly edited to make it seem like the dogs have human emotions, some featuring especially well-trained dogs, some just slapping on voice-over to inform the viewer what to think about the thing we're watching. Whatever the case, the point remains: we definitely know how to put dogs into movies.

So the question hanging over the new adaptation of the 1903 novel The Call of the Wild is: why not use a dog? Why use instead a performance-capture CGI effect that is substantially responsible for pushing the film's budget up to a level that an adaptation of a Jack London novel is simply not going earn back this far into the 21st Century? Because in addition to saving money, it would have also saved the audience's eyeballs from having to behold the freakishly over-expressive cartoon dog-thing that serves as the film's profoundly upsetting protagonist. If you've ever been curious whether other things than humans can fall into the Uncanny Valley, The Call of the Wild is here to answer that, oh my fucking word yes, they can.

It's too bad, because otherwise there's more than a little bit to enjoy about this particular version of the story (this is, incidentally, the first film released by 20th Century Fox after having been rechristened Twentieth Century Studios by the corporate overlords at Disney; in a marvelous coincidence, the last film released by the old Twentieth Century Pictures before it officially merged with Fox Film Corporation was another Call of the Wild adaption, from 1935. You know what that movie had? Real fucking dogs). It's a busy, cluttered movie, and the script desperately needed another pass, but once it gets to the part of the story promised by the title, it does a pretty damn good job of evoking something of London's animal-centric prose, despite breaking away from the particulars of London's plot.

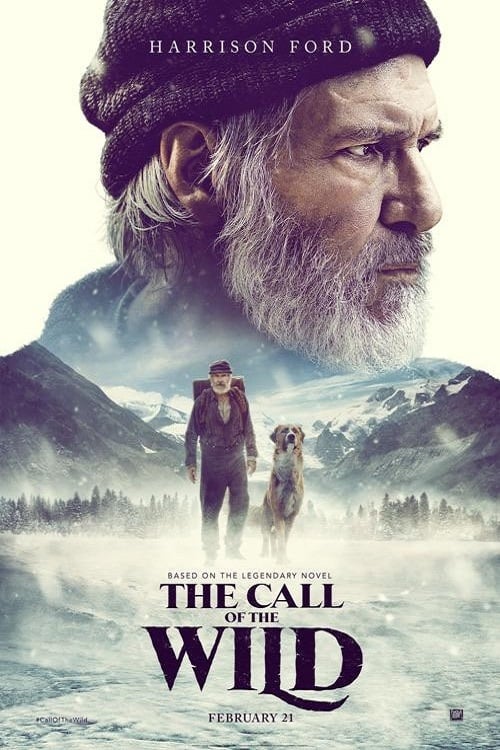

The film's revised story centers around a very large dog, Buck (played in motion capture by movement specialist Terry Notary, playing his first canine), who is kidnapped from his comfortable but confining home in the San Francisco Bay area and carted off to the Yukon, to be sold as a sled dog. Here, he is bought by the kind French-Canadian mail runner Perrault (Omar Sy), who trains him for a couple of seasons; during this time, Buck asserts himself as the leader of a dog pack, spurred on by visions of a spectral black wolf. When Perrault is obliged to divest himself of his mail operation, Buck ends up in the hands of a wretched, useless dandy named Hal (Dan Stevens), who quickly manages to fuck up an expedition to find gold in the wild. Thus does Buck end up the companion of John Thornton (Harrison Ford), a deeply beleaguered man who has a burning itch to get away from human civilisation. Buck, who has been hearing the call of the wild more and more urgently - that's what the wolf visions are about - is more than happy to follow Thornton into the parts of the Yukon that haven't been mapped yet.

It's extremely easy to split the film into its bad part and its good part: the former turns into the latter almost at the instant that Ford, with a bright twinkle in his eye, suggests that the two of them leave Dawson City to explore the grandeur of the unspoiled Yukon. And it is awfully damn grand, a mixture of location shooting and CGI that finds cinematographer Janusz Kamiński (making a rare non-Spielberg project) indulging in the glistening whiteness of bright sunshine in a crisp northern latitude to create some of the most ridiculously painterly landscape vistas of any film in some while. It's shameless in its beauty, but that's part of the appeal: London was writing from the perspective of an agog nature lover, and part of the point of The Call of the Wild in any medium is to communicate the irresistible, overwhelming pull of this landscape. Meanwhile, in a more sedate mode, it's simply wonderful to see Ford turning on his movie-star charm for a screenplay that doesn't completely bore him; this some of the best work he's done in a movie in the 21st Century, matching or bettering his similarly invested performance in 2015's The Age of Adaline, and it simply is swell to be reminded why he became famous in the first place. He combines a shy, boyish enthusiasm with a bitter, self-hating fatigue, and makes it work perfectly; he even sells me on the vile eldritch abomination hovering across from him, something no other human is able to do for even one frame of the movie.

Getting to that point requires slogging through some absolute trash, unfortunately. Buck the CGI monster is bad enough, but in the mail-sled episode that takes up the largest part of the film's first half, he's accompanied by a whole team of other CGI dogs, all of them with vivid, clearly-articulated personalities, and it is all too horrid and disgusting for words. The storytelling in the first half is also pretty brutal: this is trying to summarise a great deal of story material in only around half of a 100-minute film, which leaves the film with a certain curt, "this happens then this happens" rhythm, especially in its absolutely dire opening, where Buck's time in Santa Clara, California, as the family pet of an aging judge (Bradley Whitford, seeming miserable and exhausted) is presented so indifferently that I couldn't begin to tell you what kind of emotional reaction the filmmakers thought we were going to have. The mail sequence doesn't suffer quite so badly from that affliction, though it does race by distressingly fast. The bigger problem there is that there are two humans, the affable Québecois stereotype Perrault and the sardonic, inexplicably modern Françoise (Cara Gee): I think either approach could work (Gee's performance is weirdly electrifying), but putting them together results in a draining, achronological mismatch of tones.

Tone is, in general, a huge problem for the film. This is especially heartbreaking given that The Call of the Wild is the live-action debut of animation director Chris Sanders (who, indeed, got the job because the producers wanted an animator to work with Buck's CGI, so let's put "live-action" in some scare quotes), whose best work in that capacity mixes comedy, adventure, and pathos with effortless grace (it seems increasingly clear that his former directing partner, Dean DeBlois, got all the talent in that divorce). The film nails pathetic sentiment, in that languid final stretch; but it's not very good at adventure, and frankly terrible at comedy. When these are not the priorities, and the film shifts over to evoking the restless drive of the title, and spends its time watching Buck race around the wilderness (from a respectful distance, enough to erase the animation details that grow disturbing in close-up), it works awfully well. And that is, maybe, the only level on which a Jack London adaptation needs to work. But it does take a miserable long time to get there.

So the question hanging over the new adaptation of the 1903 novel The Call of the Wild is: why not use a dog? Why use instead a performance-capture CGI effect that is substantially responsible for pushing the film's budget up to a level that an adaptation of a Jack London novel is simply not going earn back this far into the 21st Century? Because in addition to saving money, it would have also saved the audience's eyeballs from having to behold the freakishly over-expressive cartoon dog-thing that serves as the film's profoundly upsetting protagonist. If you've ever been curious whether other things than humans can fall into the Uncanny Valley, The Call of the Wild is here to answer that, oh my fucking word yes, they can.

It's too bad, because otherwise there's more than a little bit to enjoy about this particular version of the story (this is, incidentally, the first film released by 20th Century Fox after having been rechristened Twentieth Century Studios by the corporate overlords at Disney; in a marvelous coincidence, the last film released by the old Twentieth Century Pictures before it officially merged with Fox Film Corporation was another Call of the Wild adaption, from 1935. You know what that movie had? Real fucking dogs). It's a busy, cluttered movie, and the script desperately needed another pass, but once it gets to the part of the story promised by the title, it does a pretty damn good job of evoking something of London's animal-centric prose, despite breaking away from the particulars of London's plot.

The film's revised story centers around a very large dog, Buck (played in motion capture by movement specialist Terry Notary, playing his first canine), who is kidnapped from his comfortable but confining home in the San Francisco Bay area and carted off to the Yukon, to be sold as a sled dog. Here, he is bought by the kind French-Canadian mail runner Perrault (Omar Sy), who trains him for a couple of seasons; during this time, Buck asserts himself as the leader of a dog pack, spurred on by visions of a spectral black wolf. When Perrault is obliged to divest himself of his mail operation, Buck ends up in the hands of a wretched, useless dandy named Hal (Dan Stevens), who quickly manages to fuck up an expedition to find gold in the wild. Thus does Buck end up the companion of John Thornton (Harrison Ford), a deeply beleaguered man who has a burning itch to get away from human civilisation. Buck, who has been hearing the call of the wild more and more urgently - that's what the wolf visions are about - is more than happy to follow Thornton into the parts of the Yukon that haven't been mapped yet.

It's extremely easy to split the film into its bad part and its good part: the former turns into the latter almost at the instant that Ford, with a bright twinkle in his eye, suggests that the two of them leave Dawson City to explore the grandeur of the unspoiled Yukon. And it is awfully damn grand, a mixture of location shooting and CGI that finds cinematographer Janusz Kamiński (making a rare non-Spielberg project) indulging in the glistening whiteness of bright sunshine in a crisp northern latitude to create some of the most ridiculously painterly landscape vistas of any film in some while. It's shameless in its beauty, but that's part of the appeal: London was writing from the perspective of an agog nature lover, and part of the point of The Call of the Wild in any medium is to communicate the irresistible, overwhelming pull of this landscape. Meanwhile, in a more sedate mode, it's simply wonderful to see Ford turning on his movie-star charm for a screenplay that doesn't completely bore him; this some of the best work he's done in a movie in the 21st Century, matching or bettering his similarly invested performance in 2015's The Age of Adaline, and it simply is swell to be reminded why he became famous in the first place. He combines a shy, boyish enthusiasm with a bitter, self-hating fatigue, and makes it work perfectly; he even sells me on the vile eldritch abomination hovering across from him, something no other human is able to do for even one frame of the movie.

Getting to that point requires slogging through some absolute trash, unfortunately. Buck the CGI monster is bad enough, but in the mail-sled episode that takes up the largest part of the film's first half, he's accompanied by a whole team of other CGI dogs, all of them with vivid, clearly-articulated personalities, and it is all too horrid and disgusting for words. The storytelling in the first half is also pretty brutal: this is trying to summarise a great deal of story material in only around half of a 100-minute film, which leaves the film with a certain curt, "this happens then this happens" rhythm, especially in its absolutely dire opening, where Buck's time in Santa Clara, California, as the family pet of an aging judge (Bradley Whitford, seeming miserable and exhausted) is presented so indifferently that I couldn't begin to tell you what kind of emotional reaction the filmmakers thought we were going to have. The mail sequence doesn't suffer quite so badly from that affliction, though it does race by distressingly fast. The bigger problem there is that there are two humans, the affable Québecois stereotype Perrault and the sardonic, inexplicably modern Françoise (Cara Gee): I think either approach could work (Gee's performance is weirdly electrifying), but putting them together results in a draining, achronological mismatch of tones.

Tone is, in general, a huge problem for the film. This is especially heartbreaking given that The Call of the Wild is the live-action debut of animation director Chris Sanders (who, indeed, got the job because the producers wanted an animator to work with Buck's CGI, so let's put "live-action" in some scare quotes), whose best work in that capacity mixes comedy, adventure, and pathos with effortless grace (it seems increasingly clear that his former directing partner, Dean DeBlois, got all the talent in that divorce). The film nails pathetic sentiment, in that languid final stretch; but it's not very good at adventure, and frankly terrible at comedy. When these are not the priorities, and the film shifts over to evoking the restless drive of the title, and spends its time watching Buck race around the wilderness (from a respectful distance, enough to erase the animation details that grow disturbing in close-up), it works awfully well. And that is, maybe, the only level on which a Jack London adaptation needs to work. But it does take a miserable long time to get there.