A heroine whom no one but myself will much like

Photographer and music video director Autumn de Wilde, making her deliciously confident feature film debut with the new Jane Austen adaptation Emma., has suggested in interviews that the reason for putting a period in the film's title is that "it's a period film". I think the only thing that would be funnier than if she's making that up is if she's serious. Either way, it speaks to a filmmaker who has exactly the right attitude for bringing Austen to cinematic life: with an elevated bit of wordplay that's as clever as it is obnoxious.

Not that it takes a special genius to make a movie out of Austen; indeed, the track record of Austen adaptations is maybe the strongest of any major English-language novelist. But having a special genius doesn't hurt. What a lot of Austen movies overlook is that, at heart, all of her novels are witheringly sarcastic put-downs, mercilessly stabbing at the norms of English society at the end of the 18th Century with wit, irony, and a fearless joy in taking her characters to task for their foibles. They are not handsomely sincere romantic dramas, though they use romance as their vehicle. Emma. comes four years after Whit Stillman's Love & Friendship, adapted from the abandoned novella Lady Susan, amplified that aspect of the novelist's work with comic savagery, and between the two of them, I wonder if it's too much to hope that we're at the dawn of a new wave of Austen adaptations that undercut their period richness with biting humor and a contemporary vibe that flirts with, but never commits to, anachronism.

If nothing else, this is the right approach to take to Emma, the 1815 novel about which Austen openly admitted that it had her least-likable protagonist. Miss Emma Woodhouse, played in this version of the story by Anya Taylor-Joy, is a young woman of considerable economic means, enough so that we can safely assume that she'll go through the whole of her life without ever once knowing what it is to lack. And from this position of extraordinary privilege, what Emma likes to do is to meddle in the lives of those around her - meddle and judge. In particular, she takes it upon herself to attempt to completely control the fortunes of Harriet Smith (Mia Goth), a friend from a much lower social class, and to some extent, this is where de Wilde and screenwriter Eleanor Catton have decided their version of the story will mostly live - not in the relationship between Emma and Mr. George Knightley (Johnny Flynn), a man several years older than Emma who is transparently the best romantic match for her out of all the males in the novel, assuming she decides that romance is a particular priority.

In a cast that's jammed to the rafters with wonderful performances, Flynn is obviously the weak link (which is not to say he's bad; he's perfectly okay. But perfectly okay won't cut it in this crowd), so it's nice that the filmmakers have mildly nudged the emotional stakes a bit away from "will Emma get her head out of her ass and fall in love" to "will Emma get her head out of her ass and appreciate her friends". Not that this wasn't present in the novel, and not that the new Emma. isn't generically a love story. But the characters who emerge most strongly besides Emma herself are Harriet and Miss Bates (Miranda Hart), the two women who most suffer from Emma's blithe way of barreling through life as though she knows more than the rest of humanity put together. Part of this is simply that Goth and Hart give the two best supporting performances, both finding different ways of expressing the overwhelmed feeling of liking and being liked by a young dynamo with enough burning personality that getting closed to her is a good way to end up get badly hurt; Hart, in particular, has some late moments where she has to keep an almost pathetic earnestness of affection for Emma balanced with humiliation and defeat, and she does so in what I expect to remain one of the best-acted individual scenes of 2020.* Even so, it's not just that Goth and Hart are interesting and Flynn really isn't - there feels like a choice has been made to weight this towards Emma's relationship with the women in her life, and it works very nicely.

What has not happened concurrently with this, thank God, is to soften Emma's character. If anything, de Wilde and Catton lean into what a tyrant Emma can be, and Taylor-Joy is a perfect actor to inhabit this harsher version of the character. She's great at playing intense, staring characters who refuse to soften, and while by rights this should make for an excessively cold and unsympathetic Emma, Taylor-Joy is also so adroit with punchy line deliveries and at allowing us to watch the wheels turnings in her brain without letting the other characters see it that she's made us her co-conspirators rather than witnesses. It's a comedy, after all, and an awfully funny one; drier than Love & Friendship or Clueless (the rightfully celebrated 1995 modern-dress version of the story), but with a certain amount of ironic brittleness that makes it funny in a kind of barking, bitter way.

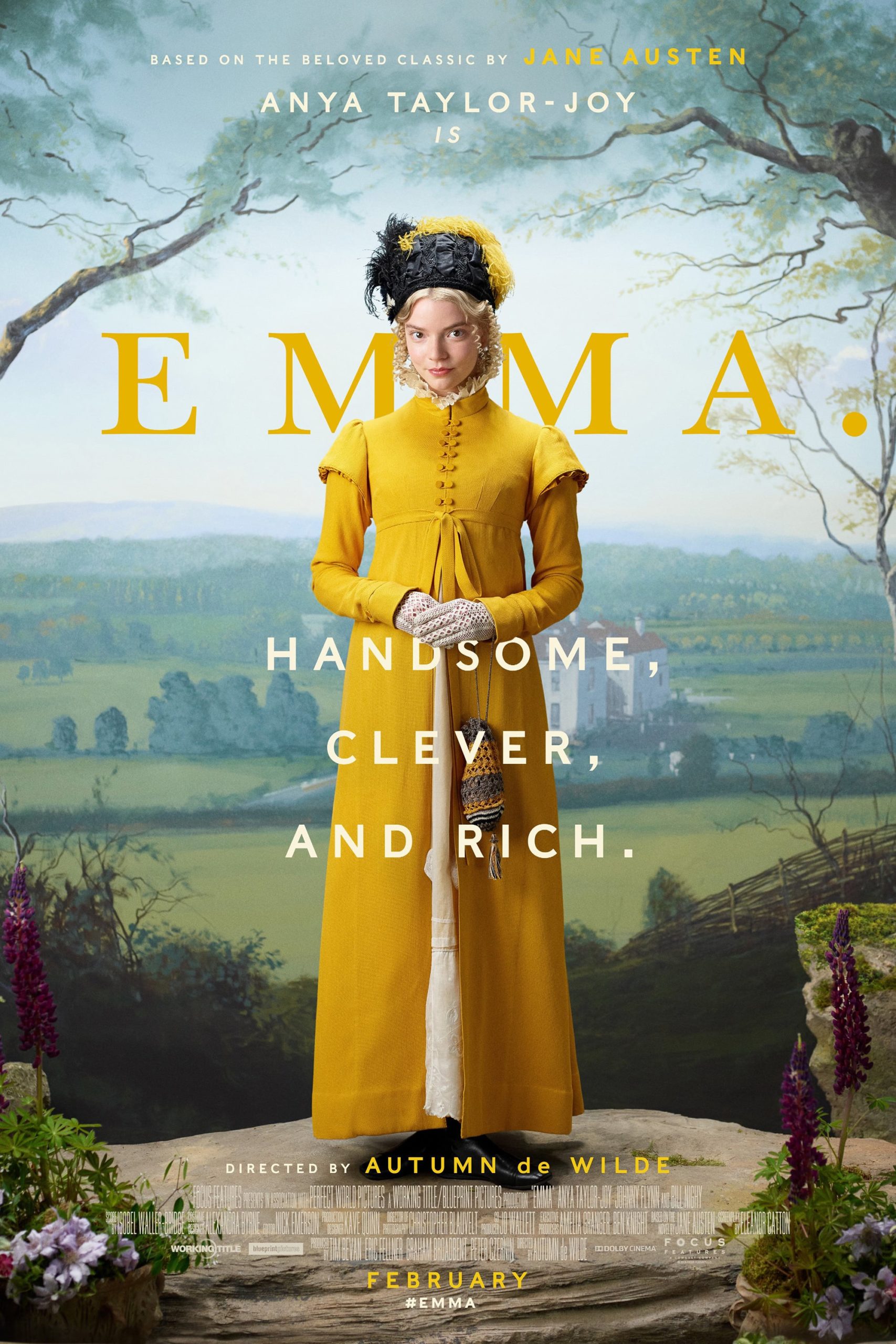

It's terrifically watchable simply as a character piece, and that's without getting into what a well-made costume drama it is. Emphasis on the costumes - Alexandra Byrne's designs deliberately go for more period accuracy than movie glamor, with the result that everybody looks a bit pinched and elongated; if the point of this novel (and any Austen novel, really) is that the cultural of England's well-off country families has a kind of formal rigidity that entraps the characters, the way that Taylor-Joy looks in all her weird tube-like dresses certainly exaggerates that. So do the compositions, which find de Wilde and cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt (Kelly Reichardt's invaluable collaborator on her last four films) obviously inspired by Yorgos Lanthimos and Robbie Ryan's mildly grotesque, geometrically merciless images in The Favourite, right down to the reliance on candlelight; it's not a direct rip-off, but there's still a feeling of spaces being ominously and oppressively rectangular in ways that force the characters into unyielding straight lines, even in the exteriors. Blauvelt softens this a little bit with some fuzzy lighting and a light pink cast that makes the whole thing feel a little warmer than the inhumane look of The Favourite, and matches nicely with the bright colors of Byrne's costumes and the expansive pastels of Kave Quinn's production design to the make the whole movie look a little bit like a gaily-decorated cake. But it is not cake: it is snarky and spiky and full of a living, aggressive energy that cuts against all of the usual sedate qualities of a costume drama; it has punchy dialogue and fast-paced blocking that let it race through its 124 minutes with indefatigable purpose that's tightly-packed without feeling rushed; and when the time comes to start letting in real human emotion and shift from the immaculately machined irony of the first two-thirds into something more uncertain and soft both tonally and visually, everybody involved nails that transition gracefully. It's not perfect - the music (both original cues and somewhat period-appropriate songs) is much too heavy for the dancing, darting lightness of the rest of it, and Flynn's relatively bland performance means that the last part of the film is far less engaging than the rest of it. But it's a hell of a ride even so, an adaptation of an unassailable classic that's willing to play with it source material rather than worship it, and foreground cinematic brio rather than literary refinement.

*Especially if the 2020 movie year ends up being all over by the end of March, but I'd still say it regardless.

Not that it takes a special genius to make a movie out of Austen; indeed, the track record of Austen adaptations is maybe the strongest of any major English-language novelist. But having a special genius doesn't hurt. What a lot of Austen movies overlook is that, at heart, all of her novels are witheringly sarcastic put-downs, mercilessly stabbing at the norms of English society at the end of the 18th Century with wit, irony, and a fearless joy in taking her characters to task for their foibles. They are not handsomely sincere romantic dramas, though they use romance as their vehicle. Emma. comes four years after Whit Stillman's Love & Friendship, adapted from the abandoned novella Lady Susan, amplified that aspect of the novelist's work with comic savagery, and between the two of them, I wonder if it's too much to hope that we're at the dawn of a new wave of Austen adaptations that undercut their period richness with biting humor and a contemporary vibe that flirts with, but never commits to, anachronism.

If nothing else, this is the right approach to take to Emma, the 1815 novel about which Austen openly admitted that it had her least-likable protagonist. Miss Emma Woodhouse, played in this version of the story by Anya Taylor-Joy, is a young woman of considerable economic means, enough so that we can safely assume that she'll go through the whole of her life without ever once knowing what it is to lack. And from this position of extraordinary privilege, what Emma likes to do is to meddle in the lives of those around her - meddle and judge. In particular, she takes it upon herself to attempt to completely control the fortunes of Harriet Smith (Mia Goth), a friend from a much lower social class, and to some extent, this is where de Wilde and screenwriter Eleanor Catton have decided their version of the story will mostly live - not in the relationship between Emma and Mr. George Knightley (Johnny Flynn), a man several years older than Emma who is transparently the best romantic match for her out of all the males in the novel, assuming she decides that romance is a particular priority.

In a cast that's jammed to the rafters with wonderful performances, Flynn is obviously the weak link (which is not to say he's bad; he's perfectly okay. But perfectly okay won't cut it in this crowd), so it's nice that the filmmakers have mildly nudged the emotional stakes a bit away from "will Emma get her head out of her ass and fall in love" to "will Emma get her head out of her ass and appreciate her friends". Not that this wasn't present in the novel, and not that the new Emma. isn't generically a love story. But the characters who emerge most strongly besides Emma herself are Harriet and Miss Bates (Miranda Hart), the two women who most suffer from Emma's blithe way of barreling through life as though she knows more than the rest of humanity put together. Part of this is simply that Goth and Hart give the two best supporting performances, both finding different ways of expressing the overwhelmed feeling of liking and being liked by a young dynamo with enough burning personality that getting closed to her is a good way to end up get badly hurt; Hart, in particular, has some late moments where she has to keep an almost pathetic earnestness of affection for Emma balanced with humiliation and defeat, and she does so in what I expect to remain one of the best-acted individual scenes of 2020.* Even so, it's not just that Goth and Hart are interesting and Flynn really isn't - there feels like a choice has been made to weight this towards Emma's relationship with the women in her life, and it works very nicely.

What has not happened concurrently with this, thank God, is to soften Emma's character. If anything, de Wilde and Catton lean into what a tyrant Emma can be, and Taylor-Joy is a perfect actor to inhabit this harsher version of the character. She's great at playing intense, staring characters who refuse to soften, and while by rights this should make for an excessively cold and unsympathetic Emma, Taylor-Joy is also so adroit with punchy line deliveries and at allowing us to watch the wheels turnings in her brain without letting the other characters see it that she's made us her co-conspirators rather than witnesses. It's a comedy, after all, and an awfully funny one; drier than Love & Friendship or Clueless (the rightfully celebrated 1995 modern-dress version of the story), but with a certain amount of ironic brittleness that makes it funny in a kind of barking, bitter way.

It's terrifically watchable simply as a character piece, and that's without getting into what a well-made costume drama it is. Emphasis on the costumes - Alexandra Byrne's designs deliberately go for more period accuracy than movie glamor, with the result that everybody looks a bit pinched and elongated; if the point of this novel (and any Austen novel, really) is that the cultural of England's well-off country families has a kind of formal rigidity that entraps the characters, the way that Taylor-Joy looks in all her weird tube-like dresses certainly exaggerates that. So do the compositions, which find de Wilde and cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt (Kelly Reichardt's invaluable collaborator on her last four films) obviously inspired by Yorgos Lanthimos and Robbie Ryan's mildly grotesque, geometrically merciless images in The Favourite, right down to the reliance on candlelight; it's not a direct rip-off, but there's still a feeling of spaces being ominously and oppressively rectangular in ways that force the characters into unyielding straight lines, even in the exteriors. Blauvelt softens this a little bit with some fuzzy lighting and a light pink cast that makes the whole thing feel a little warmer than the inhumane look of The Favourite, and matches nicely with the bright colors of Byrne's costumes and the expansive pastels of Kave Quinn's production design to the make the whole movie look a little bit like a gaily-decorated cake. But it is not cake: it is snarky and spiky and full of a living, aggressive energy that cuts against all of the usual sedate qualities of a costume drama; it has punchy dialogue and fast-paced blocking that let it race through its 124 minutes with indefatigable purpose that's tightly-packed without feeling rushed; and when the time comes to start letting in real human emotion and shift from the immaculately machined irony of the first two-thirds into something more uncertain and soft both tonally and visually, everybody involved nails that transition gracefully. It's not perfect - the music (both original cues and somewhat period-appropriate songs) is much too heavy for the dancing, darting lightness of the rest of it, and Flynn's relatively bland performance means that the last part of the film is far less engaging than the rest of it. But it's a hell of a ride even so, an adaptation of an unassailable classic that's willing to play with it source material rather than worship it, and foreground cinematic brio rather than literary refinement.

*Especially if the 2020 movie year ends up being all over by the end of March, but I'd still say it regardless.

Categories: british cinema, comedies, costume dramas, love stories, worthy adaptations