Gamblin' man

Indie filmmaking brothers Josh and Benny Safdie came up with the story for Uncut Gems many years before they finally made, when they were still just a pair of New York microbudget directors, long before they first broke through with very hip critics with 2014's Heaven Knows What and then broke through with the other critics with 2017's Good Time. And it is that latter film that was primarily responsible for Uncut Gems getting off the ground, by proving that the Safdies could work with a substantial budget and well-known actors. And this is, on the one hand, the best kind of story: filmmakers kept a scenario near and dear to their heart, slowly and stubbornly work their way from DIY invisibility all the way to having enough clout to make their movie the way they wanted to.

On the other hand, the minute I learned that the idea for Uncut Gems predated the idea for Good Time by a half-decade or more, my immediate response was "oh yeah, it sure was". The simplest way to describe Uncut Gems is that it's basically Good Time except less-than in just about every single way. That "just about" is in deference to the synth score composed by Daniel Lopatin, who did the same for the Safdies' last film, and to my mind, it's much, much better this time around. The music here has a shockingly dreamy, soaring quality, calling to mind Tangerine Dream's film scores of the 1980s, the ones that felt both yoked to a specific moment in their instrumentation and so ethereal and otherworldly in their use of those instruments that they ended up feeling timeless anyway. Uncut Gems takes this time-stamped timelessness and goes even weirder with it, since the '80s-ness of the music already feels anachronistic, and the movie takes place in 2012, so the whole thing feels a bit like a dreamy slurry anyway.

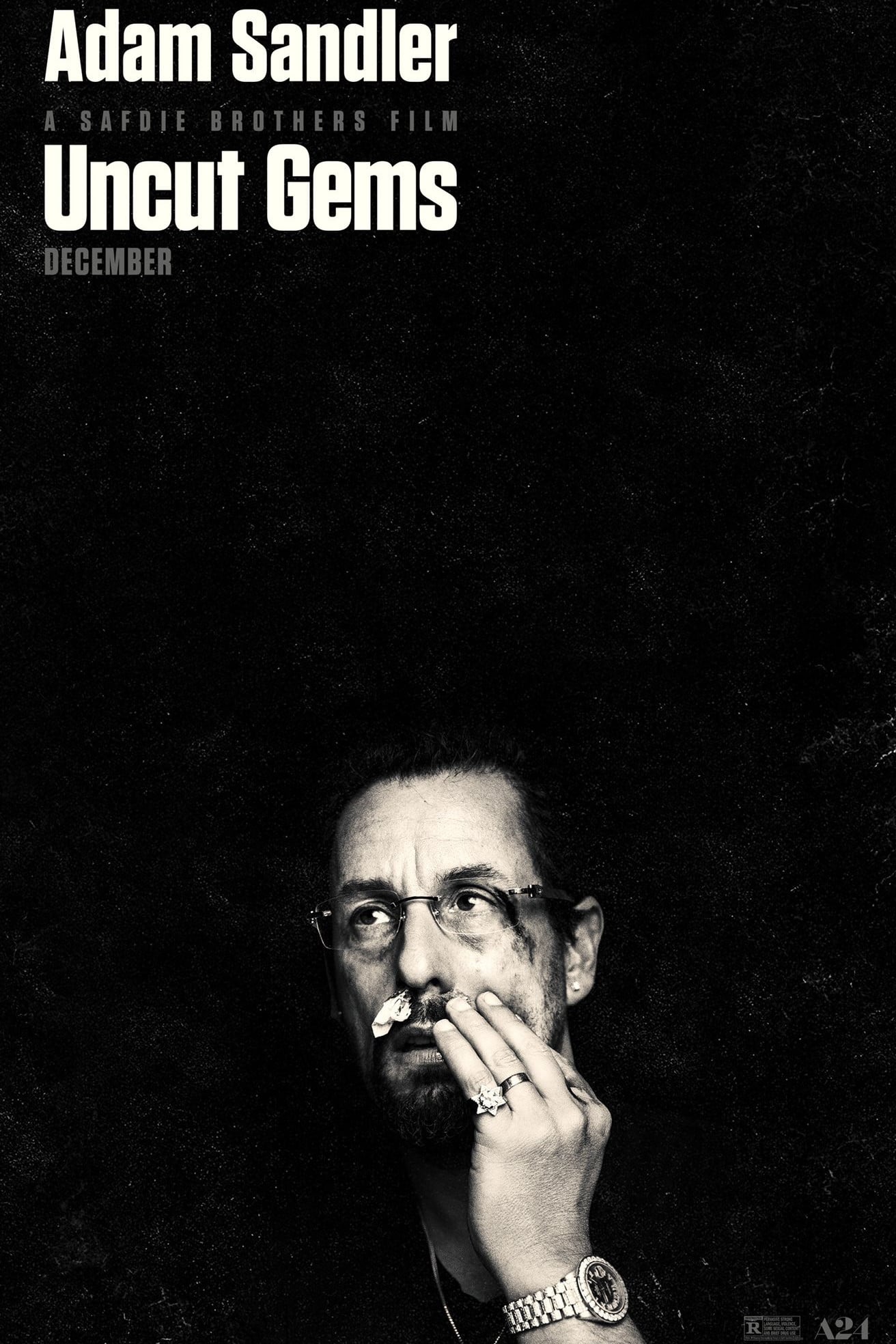

It's also very high-energy, almost triumphal at times, and it's played often and it's played loud. This turns out to be enormously important for Uncut Gems, which aims above all else to be a pounding, manic, exhausting plunge into a few days of constant agitation in the brain of a man who can't slow down for even a few minutes, or else his entire world will collapse around him. It's easily 2019's most bleary-eyed, overstimulating adrenaline shot of a movie, going far beyond Good Time's already wearying speedball energy, and doing it for no less than 135 minutes. The score isn't the only trick Uncut Gems uses to grind us into paste right alongside our anti-hero, Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler), but it is definitely the most pervasive, and the most successful. The music is transporting and sometimes extremely beautiful, but even at its most ethereal, it's never relaxing. It's the kind of music that forces your brain to turn on to process it, and Uncut Gems knows how to use this to make itself an exceedingly tiring movie to sit through. Like, in a good way. As in, for example, the outstanding thriller setpiece that ends the film, where watching men watching a basketball game becomes terrifying and heartbreaking and so intense that it's physically stressful to watch.

The story that needs to be so draining and miserable to sit through follows a few days in Howard's life as he waits for the big score that's just around the corner, presumably one of many. He's the owner of an upscale jewelry shop in the Manhattan Diamond District, and after much effort and time, he has acquired a rock studded with uncut black opals from a mine in Ethiopia. He's planning to sell it at auction to pay off his debts to the increasingly impatient loan shark Arno (Eric Bogosian), but there is a wrinkle. The stone arrives the day that Boston Celtics basketball superstar Kevin Garnett (playing himself) has come to peruse the shop, and he immediately falls in love with the opal himself, begging to borrow it in the belief that it will help his playing. Which leads to several days of panic as the stone keeps failing to show up where Howard's go-between Demany (LaKeith Stanfield) promises it will. Meanwhile, Howard's marriage to Dinah (Idina Menzel) is functionally over, and they're just waiting till after Passover to officially announce this fact to their children; he spends his time instead with his girlfriend and employee Julia (Julia Fox), whom he keeps in an expensive downtown apartment. And to cap it all off, he's a gambling addict, which seems to be the actual driving force behind all of the other stuff.

Exhausting to type all of that out; exhausting, I imagine, to read it; exhausting to watch it. And this raises the question: does Uncut Gems have anything else besides an admirably committed desire to run the viewer into the ground? The story, which I didn't really even get to in that massive block of text, is just the stuff of watching a gambler desperately run from plate to plate, keeping them all spinning, until his windfall comes along; the detail of setting it in the Diamond District is at least a little bit new (it does not, however, do anything with this setting, other than enjoy the sleekness of all the glass display cases this involves placing into the central set, and the pervasive Judaism of it would never have shown up in a '40s or '50s movie, but this is basically just a stock film noir situation. And it plays out pretty much according to formula, with the exception that a film noir would have had the good sense not to make gambling so damn easy for Howard: without giving anything specific away, though you should probably be aware of SPOILERS FOR THE REST OF THIS PARAGRAPH, Uncut Gems is basically the story of a sweaty, miserably desperate huckster who always wins, so much so that the ending comes across as an equally sweaty and desperate gesture by writers who've realised too late that they fucked up and made their angry, acid-laced thriller end happily. And this, as much as anything, is where it feels like the Safdies have regressed to snotty juvenalia. It's a film with a vibe of sneering nihilism that's both bleaker and less convincing than Good Time; if I wanted to be generous, I might look to the omnipresent Jewishness of the film, and draw a line to another pair of Jewish filmmaking brothers, Joel and Ethan Coen, whose A Serious Man ends with a similarly arbitrary "and then things got really bad" gesture, though this has none of the loopy black comedy or exquisite irony of that film.

The point being: Uncut Gems doesn't do anything new, and it doesn't say anything new, and so it just feels pretty... fine? Being formulaic doesn't mean it can't also be well-executed, and in some ways it certainly is. The score is miraculous. And I've also got nothing to complain about the harsh lighting and smeary grain in Darius Khondji's cinematography, some of his best work of the 21st Century, bringing an ugly, hostile aggression to the proceedings that fits well with the sense of everything being pointless and shitty, while also contributing to the overstimulating muchness of the film. Take out those two things, and I don't really know what's left. Sandler is giving a lot of himself in playing a perfectly unlikable asshole who we nevertheless end up rooting for mostly because the film makes us accomplices to his schemes; but even though he's working hard, I don't know how far he gets. The character's accent and speaking patterns feel a little shticky, still; rough and mean rather than dopey and obnoxious, but not all that far from the actor's comic work back in the '90s when he still actually cared about being a comedian. The rest of the cast is capable of some terrific work (Menzel is especially impressive, given how little the script has provided for her; I also greatly enjoyed Keith Williams Richards's comically annoyed reactions as Arno's mercurial henchman), but the film doesn't care to do anything with them.

And maybe this wouldn't matter; maybe this could just be a yarn well-told (with some exceptions, like the thematically dubious, tasteless, and narratively unproductive opening scene in Ethiopia). But it's so relentless. At a certain point, monotony sets in. It did with Good Time, too, but that was 34 minutes shorter than this. Here in Uncut Gems, one figures out pretty early on what the experience of watching it is always going to be, and the movie never does anything to change things up till that basketball-thriller finale. It takes a lot to pack this much momentum into every minute of a movie, but my admiration for the Safdies' commitment doesn't quite translate into enjoying the experience of watching the end result, or quite understanding what I was meant to have gotten out of doing so.

On the other hand, the minute I learned that the idea for Uncut Gems predated the idea for Good Time by a half-decade or more, my immediate response was "oh yeah, it sure was". The simplest way to describe Uncut Gems is that it's basically Good Time except less-than in just about every single way. That "just about" is in deference to the synth score composed by Daniel Lopatin, who did the same for the Safdies' last film, and to my mind, it's much, much better this time around. The music here has a shockingly dreamy, soaring quality, calling to mind Tangerine Dream's film scores of the 1980s, the ones that felt both yoked to a specific moment in their instrumentation and so ethereal and otherworldly in their use of those instruments that they ended up feeling timeless anyway. Uncut Gems takes this time-stamped timelessness and goes even weirder with it, since the '80s-ness of the music already feels anachronistic, and the movie takes place in 2012, so the whole thing feels a bit like a dreamy slurry anyway.

It's also very high-energy, almost triumphal at times, and it's played often and it's played loud. This turns out to be enormously important for Uncut Gems, which aims above all else to be a pounding, manic, exhausting plunge into a few days of constant agitation in the brain of a man who can't slow down for even a few minutes, or else his entire world will collapse around him. It's easily 2019's most bleary-eyed, overstimulating adrenaline shot of a movie, going far beyond Good Time's already wearying speedball energy, and doing it for no less than 135 minutes. The score isn't the only trick Uncut Gems uses to grind us into paste right alongside our anti-hero, Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler), but it is definitely the most pervasive, and the most successful. The music is transporting and sometimes extremely beautiful, but even at its most ethereal, it's never relaxing. It's the kind of music that forces your brain to turn on to process it, and Uncut Gems knows how to use this to make itself an exceedingly tiring movie to sit through. Like, in a good way. As in, for example, the outstanding thriller setpiece that ends the film, where watching men watching a basketball game becomes terrifying and heartbreaking and so intense that it's physically stressful to watch.

The story that needs to be so draining and miserable to sit through follows a few days in Howard's life as he waits for the big score that's just around the corner, presumably one of many. He's the owner of an upscale jewelry shop in the Manhattan Diamond District, and after much effort and time, he has acquired a rock studded with uncut black opals from a mine in Ethiopia. He's planning to sell it at auction to pay off his debts to the increasingly impatient loan shark Arno (Eric Bogosian), but there is a wrinkle. The stone arrives the day that Boston Celtics basketball superstar Kevin Garnett (playing himself) has come to peruse the shop, and he immediately falls in love with the opal himself, begging to borrow it in the belief that it will help his playing. Which leads to several days of panic as the stone keeps failing to show up where Howard's go-between Demany (LaKeith Stanfield) promises it will. Meanwhile, Howard's marriage to Dinah (Idina Menzel) is functionally over, and they're just waiting till after Passover to officially announce this fact to their children; he spends his time instead with his girlfriend and employee Julia (Julia Fox), whom he keeps in an expensive downtown apartment. And to cap it all off, he's a gambling addict, which seems to be the actual driving force behind all of the other stuff.

Exhausting to type all of that out; exhausting, I imagine, to read it; exhausting to watch it. And this raises the question: does Uncut Gems have anything else besides an admirably committed desire to run the viewer into the ground? The story, which I didn't really even get to in that massive block of text, is just the stuff of watching a gambler desperately run from plate to plate, keeping them all spinning, until his windfall comes along; the detail of setting it in the Diamond District is at least a little bit new (it does not, however, do anything with this setting, other than enjoy the sleekness of all the glass display cases this involves placing into the central set, and the pervasive Judaism of it would never have shown up in a '40s or '50s movie, but this is basically just a stock film noir situation. And it plays out pretty much according to formula, with the exception that a film noir would have had the good sense not to make gambling so damn easy for Howard: without giving anything specific away, though you should probably be aware of SPOILERS FOR THE REST OF THIS PARAGRAPH, Uncut Gems is basically the story of a sweaty, miserably desperate huckster who always wins, so much so that the ending comes across as an equally sweaty and desperate gesture by writers who've realised too late that they fucked up and made their angry, acid-laced thriller end happily. And this, as much as anything, is where it feels like the Safdies have regressed to snotty juvenalia. It's a film with a vibe of sneering nihilism that's both bleaker and less convincing than Good Time; if I wanted to be generous, I might look to the omnipresent Jewishness of the film, and draw a line to another pair of Jewish filmmaking brothers, Joel and Ethan Coen, whose A Serious Man ends with a similarly arbitrary "and then things got really bad" gesture, though this has none of the loopy black comedy or exquisite irony of that film.

The point being: Uncut Gems doesn't do anything new, and it doesn't say anything new, and so it just feels pretty... fine? Being formulaic doesn't mean it can't also be well-executed, and in some ways it certainly is. The score is miraculous. And I've also got nothing to complain about the harsh lighting and smeary grain in Darius Khondji's cinematography, some of his best work of the 21st Century, bringing an ugly, hostile aggression to the proceedings that fits well with the sense of everything being pointless and shitty, while also contributing to the overstimulating muchness of the film. Take out those two things, and I don't really know what's left. Sandler is giving a lot of himself in playing a perfectly unlikable asshole who we nevertheless end up rooting for mostly because the film makes us accomplices to his schemes; but even though he's working hard, I don't know how far he gets. The character's accent and speaking patterns feel a little shticky, still; rough and mean rather than dopey and obnoxious, but not all that far from the actor's comic work back in the '90s when he still actually cared about being a comedian. The rest of the cast is capable of some terrific work (Menzel is especially impressive, given how little the script has provided for her; I also greatly enjoyed Keith Williams Richards's comically annoyed reactions as Arno's mercurial henchman), but the film doesn't care to do anything with them.

And maybe this wouldn't matter; maybe this could just be a yarn well-told (with some exceptions, like the thematically dubious, tasteless, and narratively unproductive opening scene in Ethiopia). But it's so relentless. At a certain point, monotony sets in. It did with Good Time, too, but that was 34 minutes shorter than this. Here in Uncut Gems, one figures out pretty early on what the experience of watching it is always going to be, and the movie never does anything to change things up till that basketball-thriller finale. It takes a lot to pack this much momentum into every minute of a movie, but my admiration for the Safdies' commitment doesn't quite translate into enjoying the experience of watching the end result, or quite understanding what I was meant to have gotten out of doing so.