The dark age

You might say, if you were a terrible person with a weakness for cheap wordplay, that Shadow is an anti-Hero. It is the work of director Zhang Yimou, one of the most celebrated directors in the world during the 1990s for his delicate character dramas in recent historical settings (the likes of 1990's Ju Dou, 1991's Raise the Red Lantern, and 1994's To Live), though his most popular films, at least for English-speaking audiences, have undoubtedly been his handful of martial arts epics set in Ancient China, starting with 2002's Hero and 2004's House of Flying Daggers. And, I suppose I have to say, 2016's The Great Wall, which is the highest-grossing film of his career by a whole lot, though not because it is anything close to his best work.

Shadow is Zhang's latest entry in this secondary career path, and it is certainly the most like Hero of anything he's done since 2002, while also being sort of exactly the opposite of Hero. Most obviously, it goes precisely the other direction from the earlier film's celebrated visual style. Hero, you likely know, is a film done up in extremely oversaturated solid colors: it has Red Sequence, a Yellow Sequence, a Blue Sequence, a Black and White Sequence, a White Framework Narrative, and several Green Bits. It's color-coded according to setting, mood, and the veracity of the version of events we're hearing.

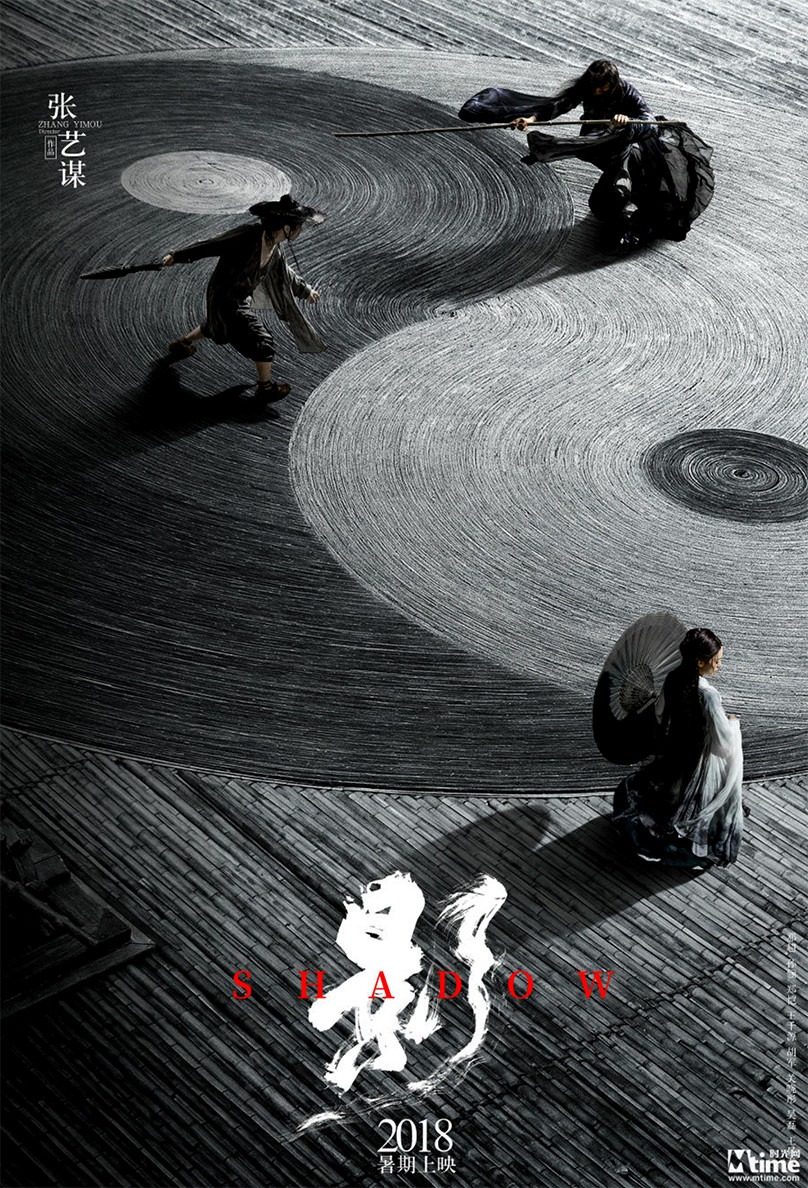

Shadow, meanwhile, is black-and-white, though it is a peculiar and extremely laborious sort of black-and-white. Technically speaking, the entire film is shot in color on high-end digital cameras that capture the color data in as much exacting detail as anyone could possibly need. It is, in fact, the sets and costumes that are entirely in black-and-white; there's at least one shot of a riverbank that I'm fairly certain was desaturated in post-production, but when we are at the point of saying "I am confident that not fewer than eight seconds of this 116-minute film was done digitally, you cheater", we might as well just stick with the simple version: this is a color film shot in a monochromatic world. Human flesh tones are literally the only source of any color whatsoever in the first half of the movie, after which point blood is also introduced. And while it's murky, greyish blood for the most part, it pops like you wouldn't believe after one's eye has gotten good and relaxed from having so little color to parse.

That already gives us a whole lot to work with: just the fact of doing something so damnably peculiar is worth grappling with. For there is the question not just of "why is Shadow in black-and-white?", which has an answer already baked into its title, but "why is Shadow this specific bizarre fake version of black-and-white?" And the answer clearly isn't, as some critics would seem to suggest, to make the blood pop. You could make that happen in any halfway decent piece of color correction software over a long weekend. Rather, I think the point of this is that there's a kind of distinct, almost indescrible texture to the monochrome that comes this way. It's not exactly black and white. It's slightly unstable, with a little ghost of brown here, an aura of blue there. And, of course, there are the skin tones, always showing up as incongruously warm and pink in the presence of so much grey. The best I can come up with is that it is to color cinematography as John Cage's 4'33 is to music: it strips away every bit of stimulus not to demonstrate an absence but to amplify the presence of what is left. That is to say: a black-and-white movie is just black-and-white. Shadow is actively colorless in a way that remains persistently noticeable and abnormal.

To the larger question, of why Shadow is in any flavor of black-and-white, the answer is staring us in the face pretty constantly. It is a film about duality, embodied in the concept of yin and yang, dark and light, the symbol for which appears on the ground of one of the film's most important sets (if I am not mistaken, the Mandarin word for "shadow" is etymologically linked to the word for "dark"). The film is built on dualism: the protagonist is two characters played by the same character, one deeply embroiled in the politicking of the day, and one an invisible nobody. The structure is built around two roughly equal parts, with the first half a complicated historical political drama and the second half a wuxia action movie. The only thing that's grey is the morality: this is basically a costume drama film noir, in which every character is a shifting mixture of good and wicked impulses.

Offering a plot synopsis would be laughably difficult: practically every single line of dialogue in the first half contributes something important to the thick political intrigue of the Three Kingdoms period in the 3rd Century. The shortest version I can manage is that Ziyu (Deng Chao) is a commander in the service of the King of Pei (Zheng Kai), who has suffered defeat at the hands of Yang Cang (Hu Jun) of the Kingdom of Yang. The king's attempts to secure peace are degrading and cowardly, and Ziyu has gone against his orders, demanding a rematch with Yang Cang. In fact, Ziyu has been so badly wounded that he can't possibly fight; he and his wife Xiao Ai (Li Sun) have been training Jingzhou (also Deng), a commoner who looks just like Ziyu, in the traditional Pei fighting technique using metal umbrellas as weapons. Jingzhou is going nowhere fast in his training, until Xiao Ai comes up with yet another duality to explore: rather than following the rigid masculine fighting style that cause Ziyu to lose, she proposes to train Jingzhou herself, in a more fluid, defensive, feminine style. This hands-on approach of course means that Xiao Ai and Jingzhou will develop strong feelings for each other, the kind that are surely going to make this already fraught situation even nastier if it comes out.

The combination of character drama, political romance, and martial arts movie is a whole lot to keep track of, and Shadow is merciless towards the viewer unprepared to devote full attention to all of the small details that keep accumulating, details which are already nigh unto impenetrable for a viewer (like myself) whose knowledge of the Three Kingdoms period is more theoretical than actual. It is a portrait of court intrigue that is suffused with corruption and rot - another way the film reverses Hero, with its calculated celebration of centralised authority. It does, in its way, valorise collective action in its fantastic late battle scenes (which are, perhaps on purpose, more visually exciting and elaborately choreographed than the one-on-one fights, as good as those are. The action is, in general, an unvarnished strength of the film: nothing as virtuosic as the best moments of Hero or House of Flying Daggers, but it's certainly a fair contribution to the annals of wuxia), but the overall vibe is so bitter and cynical that it's hard to call this a propaganda film, even on the edges.

Granting that, the whole mass of the movie is a thrilling experience. The dynamic between Ziyu, Xiao Ai, and Jingzhou is a strong foundation for everything else; it's the most psychologically rich of Zhang's action movies, and it only grows richer as it enters its end game. Deng and Sun also give superb performances: the former obviously has the more showy, difficult job, and he aces it (the differences between Ziyu, Jingzhou, and Jingzhou-as-Ziyu are clear at every moment), though Sun's work requires subtler touches, and she's maybe even more impressive for it. With those two - three? - as a nucleus, the torrent of political machinations is somewhat easier to take, and process not for its historical importance, but for its human impact. And the final stretch of the movie, shifting from one-on-one fights to a sprawling battle back into a battle of wills between individuals - all of it punctuated by overwhelming splats of red. It's a wonderful accomplishment, and the film's lack of attention in English-language criticism is somewhat baffling (it's a world-class filmmaker working in his most popular genre - fifteen years ago, this would have received a massive rollout, by the standards of subtitled films). But it has the goods, both as spectacle and as an enjoyable dense political thriller, and it feels like the sort of thing whose reputation will only grow as people stumble across it in the years to come.

Shadow is Zhang's latest entry in this secondary career path, and it is certainly the most like Hero of anything he's done since 2002, while also being sort of exactly the opposite of Hero. Most obviously, it goes precisely the other direction from the earlier film's celebrated visual style. Hero, you likely know, is a film done up in extremely oversaturated solid colors: it has Red Sequence, a Yellow Sequence, a Blue Sequence, a Black and White Sequence, a White Framework Narrative, and several Green Bits. It's color-coded according to setting, mood, and the veracity of the version of events we're hearing.

Shadow, meanwhile, is black-and-white, though it is a peculiar and extremely laborious sort of black-and-white. Technically speaking, the entire film is shot in color on high-end digital cameras that capture the color data in as much exacting detail as anyone could possibly need. It is, in fact, the sets and costumes that are entirely in black-and-white; there's at least one shot of a riverbank that I'm fairly certain was desaturated in post-production, but when we are at the point of saying "I am confident that not fewer than eight seconds of this 116-minute film was done digitally, you cheater", we might as well just stick with the simple version: this is a color film shot in a monochromatic world. Human flesh tones are literally the only source of any color whatsoever in the first half of the movie, after which point blood is also introduced. And while it's murky, greyish blood for the most part, it pops like you wouldn't believe after one's eye has gotten good and relaxed from having so little color to parse.

That already gives us a whole lot to work with: just the fact of doing something so damnably peculiar is worth grappling with. For there is the question not just of "why is Shadow in black-and-white?", which has an answer already baked into its title, but "why is Shadow this specific bizarre fake version of black-and-white?" And the answer clearly isn't, as some critics would seem to suggest, to make the blood pop. You could make that happen in any halfway decent piece of color correction software over a long weekend. Rather, I think the point of this is that there's a kind of distinct, almost indescrible texture to the monochrome that comes this way. It's not exactly black and white. It's slightly unstable, with a little ghost of brown here, an aura of blue there. And, of course, there are the skin tones, always showing up as incongruously warm and pink in the presence of so much grey. The best I can come up with is that it is to color cinematography as John Cage's 4'33 is to music: it strips away every bit of stimulus not to demonstrate an absence but to amplify the presence of what is left. That is to say: a black-and-white movie is just black-and-white. Shadow is actively colorless in a way that remains persistently noticeable and abnormal.

To the larger question, of why Shadow is in any flavor of black-and-white, the answer is staring us in the face pretty constantly. It is a film about duality, embodied in the concept of yin and yang, dark and light, the symbol for which appears on the ground of one of the film's most important sets (if I am not mistaken, the Mandarin word for "shadow" is etymologically linked to the word for "dark"). The film is built on dualism: the protagonist is two characters played by the same character, one deeply embroiled in the politicking of the day, and one an invisible nobody. The structure is built around two roughly equal parts, with the first half a complicated historical political drama and the second half a wuxia action movie. The only thing that's grey is the morality: this is basically a costume drama film noir, in which every character is a shifting mixture of good and wicked impulses.

Offering a plot synopsis would be laughably difficult: practically every single line of dialogue in the first half contributes something important to the thick political intrigue of the Three Kingdoms period in the 3rd Century. The shortest version I can manage is that Ziyu (Deng Chao) is a commander in the service of the King of Pei (Zheng Kai), who has suffered defeat at the hands of Yang Cang (Hu Jun) of the Kingdom of Yang. The king's attempts to secure peace are degrading and cowardly, and Ziyu has gone against his orders, demanding a rematch with Yang Cang. In fact, Ziyu has been so badly wounded that he can't possibly fight; he and his wife Xiao Ai (Li Sun) have been training Jingzhou (also Deng), a commoner who looks just like Ziyu, in the traditional Pei fighting technique using metal umbrellas as weapons. Jingzhou is going nowhere fast in his training, until Xiao Ai comes up with yet another duality to explore: rather than following the rigid masculine fighting style that cause Ziyu to lose, she proposes to train Jingzhou herself, in a more fluid, defensive, feminine style. This hands-on approach of course means that Xiao Ai and Jingzhou will develop strong feelings for each other, the kind that are surely going to make this already fraught situation even nastier if it comes out.

The combination of character drama, political romance, and martial arts movie is a whole lot to keep track of, and Shadow is merciless towards the viewer unprepared to devote full attention to all of the small details that keep accumulating, details which are already nigh unto impenetrable for a viewer (like myself) whose knowledge of the Three Kingdoms period is more theoretical than actual. It is a portrait of court intrigue that is suffused with corruption and rot - another way the film reverses Hero, with its calculated celebration of centralised authority. It does, in its way, valorise collective action in its fantastic late battle scenes (which are, perhaps on purpose, more visually exciting and elaborately choreographed than the one-on-one fights, as good as those are. The action is, in general, an unvarnished strength of the film: nothing as virtuosic as the best moments of Hero or House of Flying Daggers, but it's certainly a fair contribution to the annals of wuxia), but the overall vibe is so bitter and cynical that it's hard to call this a propaganda film, even on the edges.

Granting that, the whole mass of the movie is a thrilling experience. The dynamic between Ziyu, Xiao Ai, and Jingzhou is a strong foundation for everything else; it's the most psychologically rich of Zhang's action movies, and it only grows richer as it enters its end game. Deng and Sun also give superb performances: the former obviously has the more showy, difficult job, and he aces it (the differences between Ziyu, Jingzhou, and Jingzhou-as-Ziyu are clear at every moment), though Sun's work requires subtler touches, and she's maybe even more impressive for it. With those two - three? - as a nucleus, the torrent of political machinations is somewhat easier to take, and process not for its historical importance, but for its human impact. And the final stretch of the movie, shifting from one-on-one fights to a sprawling battle back into a battle of wills between individuals - all of it punctuated by overwhelming splats of red. It's a wonderful accomplishment, and the film's lack of attention in English-language criticism is somewhat baffling (it's a world-class filmmaker working in his most popular genre - fifteen years ago, this would have received a massive rollout, by the standards of subtitled films). But it has the goods, both as spectacle and as an enjoyable dense political thriller, and it feels like the sort of thing whose reputation will only grow as people stumble across it in the years to come.