Fait la chose juste

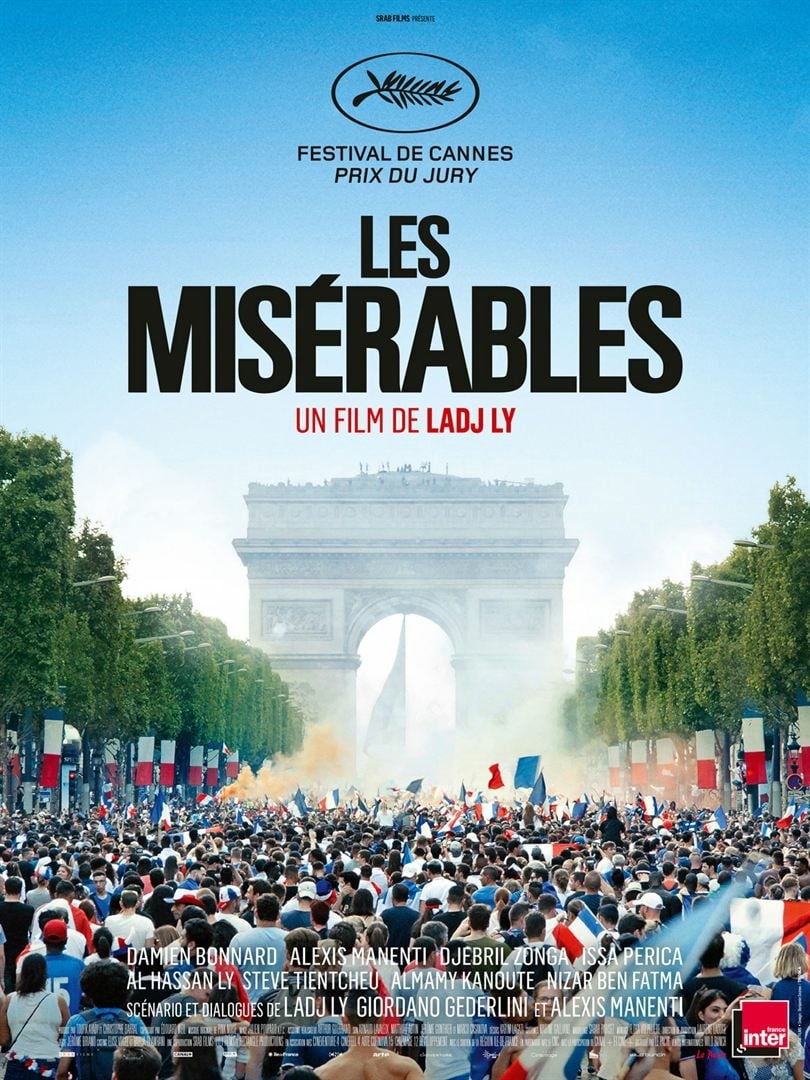

Let us start with the title. The new film titled Les Misérables is not an adaptation of Victor Hugo's 1862 novel, already one of the most commonly-adapted books in cinema history. It is, rather, a story that takes up the same concerns as Hugo, approaching them in their 21st Century embodiment. So this tale of the dispossessed urban poor of Paris abandons the books religious themes and adds racial and ethnic tensions, while preserving the core idea that a society that has robbed its most desperate members of the means to live a decent life is no society worth preserving in its current state. It also maintains the idea that the primary defenders of the social order, the police, are both the first big problem that needs to be solved, while also being helpless victims of the system themselves. And this is where I start to get a little bit uncertain about what first-time writer-director Ladj Ly and his co-writers Giordano Gederlini & Alexis Manenti were up to in borrowing Hugo's title: borrowing Les Misérables as the title of a story about oppressed, angry immigrants is a bold and confident and right choice, but using it is as the title of a film told through the POV of three cops? That seems to be missing the point at least a little bit, I have to say.

In fairness, the film's POV is diffuse enough that saying it's about three cops is a bit limiting. It is, to be sure, mostly about the cops: Chris (Manenti) is a flippant racist, Gwada (Djebril Zonga) is from the same neighborhood in Montfermeil (a main location in Hugo's novel, now mostly the home to North African immigrant communities.) that the three are policing, and Ruiz (Damien Bonnard) has just transferred this very day, conveniently giving us a conduit to learn about the ins and outs of this neighborhood's culture, and providing the closest the film has to a persistent point of audience identification. We meet other people as well, moving through every corner of the neighborhood and seeing how everybody from kids to community leaders to other outsiders perceive the place and the people who live there; it is a very self-consciously kaleiodscopic bit of world-building. But mostly, we follow the cops, in something not much longer than real time, as they are called upon to resolve a somewhat dumb prank in which a group of local adolescents stole a lion cub from a circus; their attempts to resolve this situation are ham-fisted enough, despite Gwada's attempts to serve as diplomat, that it ends up triggering a small but extremely frantic riot.

If that sounds quite a bit like Spike Lee's 1989 masterpiece Do the Right Thing, it absolutely should; the ethnically heterogeneous trio of leads is hopefully enough to also point is in the direction of Mathieu Kassovitz's 1995 La Haine, and it is certainly not the only way that Les Misérables draws from that film, either. That is to say: Ly and his collaborators aren't really doing much that's new. They're doing it well, to be clear: Les Misérables is a passionate and angry and living piece of cinema, keyed up by the tensions running through French society and ready to grapple with them head on. The film was inspired by riots in the Paris suburbs in the fall of 2005, in which young people from African communities protested against the brutality of the police and the indifference of the government to their suffering. Those events loom heavily in the background of Les Misérables, mentioned by name and more generally informing the sense of growing tension as they day drags on with no satisfaction for anybody, and as the three cops in their very different ways all realise that they are doing a poor job of diffusing that tension.

The fraught undercurrents that thus play out are explored with what I presume to be a great deal of acuity and delicacy, enough for the film to win the Jury Prize at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival (in a tie with the Brazilian Bacurau). I confess that my thick-witted American eyes don't see anything here that isn't present in three or four French movies at any well-curated international film festival. There are, unquestionably, some moments of true masterpiece-level filmmaking on display, the most impressive of which opens the film: Issa (Issa Perica), who will prove to be the most significant figure in the film after the cops, bursts out of his apartment wearing the French flag like a cape as he goes to join his friends in celebrating France's 2018 World Cup victory. The symbolism is so obvious that it would humiliate me and you both if I were to spell it out, but Ly handles it deftly, filming the moment with a documentary-like looseness, capturing the sounds and spaces of the neighborhood while also capturing something particular about Issa himself, not as a French citizen nor as a French citizen of African descent, but as an enthusiastic kid in the world.

Moments like these are scattered throughout Les Misérables, and they're the best thing the film has to offer. I'm not entirely sure they cohere into a portrait of a community the way the filmmakers want them to; at 102 minutes, this the rare film that I think would obviously benefit from being longer, to give us more space to sink into the location, possibly spending more than just one day there. Beyond this, Ly and his crew, most notably cinematographer Julien Poupard and editor Flora Volpelière, have elected to present the film in the most safe, even banal aesthetic register possible. And sure, "safe" means something different here than it would in an American blockbuster, but French-made movies about poor people have a formula just like anything else, and that formula involves shaky hand-held, lots of street noise in the background, cutting arrhythmically in the middle of lines of dialogue and often cutting from one angle of a person to another angle of the same person, and keeping the shot scale close enough that we start to feel slightly trapped with the subjects. It can be done well or poorly, and it's being done well in Les Misérables. But it looks, moves, and sounds exactly the way I assumed it would when all I knew was the logline.

Part of me wonders if that's even the point. 24 years after La Haine, nothing has changed in French society, so we need to have the same stories told the same way to underscore that. On the other hand, the sort of generic "European art cinema" vibe to the style makes me feel like that's a generous reading. Les Misérables has something it's very urgently eager to say, and it says it with furious passion; but dramatically and stylistically, it doesn't have the same radicalism as it preaches. And that does blunt the impact of its passion somewhat. Then again, Hugo's novel also packed radical messages into a bourgeois-friendly art form, so perhaps this is just part of the heritage of being Les Misérables.

In fairness, the film's POV is diffuse enough that saying it's about three cops is a bit limiting. It is, to be sure, mostly about the cops: Chris (Manenti) is a flippant racist, Gwada (Djebril Zonga) is from the same neighborhood in Montfermeil (a main location in Hugo's novel, now mostly the home to North African immigrant communities.) that the three are policing, and Ruiz (Damien Bonnard) has just transferred this very day, conveniently giving us a conduit to learn about the ins and outs of this neighborhood's culture, and providing the closest the film has to a persistent point of audience identification. We meet other people as well, moving through every corner of the neighborhood and seeing how everybody from kids to community leaders to other outsiders perceive the place and the people who live there; it is a very self-consciously kaleiodscopic bit of world-building. But mostly, we follow the cops, in something not much longer than real time, as they are called upon to resolve a somewhat dumb prank in which a group of local adolescents stole a lion cub from a circus; their attempts to resolve this situation are ham-fisted enough, despite Gwada's attempts to serve as diplomat, that it ends up triggering a small but extremely frantic riot.

If that sounds quite a bit like Spike Lee's 1989 masterpiece Do the Right Thing, it absolutely should; the ethnically heterogeneous trio of leads is hopefully enough to also point is in the direction of Mathieu Kassovitz's 1995 La Haine, and it is certainly not the only way that Les Misérables draws from that film, either. That is to say: Ly and his collaborators aren't really doing much that's new. They're doing it well, to be clear: Les Misérables is a passionate and angry and living piece of cinema, keyed up by the tensions running through French society and ready to grapple with them head on. The film was inspired by riots in the Paris suburbs in the fall of 2005, in which young people from African communities protested against the brutality of the police and the indifference of the government to their suffering. Those events loom heavily in the background of Les Misérables, mentioned by name and more generally informing the sense of growing tension as they day drags on with no satisfaction for anybody, and as the three cops in their very different ways all realise that they are doing a poor job of diffusing that tension.

The fraught undercurrents that thus play out are explored with what I presume to be a great deal of acuity and delicacy, enough for the film to win the Jury Prize at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival (in a tie with the Brazilian Bacurau). I confess that my thick-witted American eyes don't see anything here that isn't present in three or four French movies at any well-curated international film festival. There are, unquestionably, some moments of true masterpiece-level filmmaking on display, the most impressive of which opens the film: Issa (Issa Perica), who will prove to be the most significant figure in the film after the cops, bursts out of his apartment wearing the French flag like a cape as he goes to join his friends in celebrating France's 2018 World Cup victory. The symbolism is so obvious that it would humiliate me and you both if I were to spell it out, but Ly handles it deftly, filming the moment with a documentary-like looseness, capturing the sounds and spaces of the neighborhood while also capturing something particular about Issa himself, not as a French citizen nor as a French citizen of African descent, but as an enthusiastic kid in the world.

Moments like these are scattered throughout Les Misérables, and they're the best thing the film has to offer. I'm not entirely sure they cohere into a portrait of a community the way the filmmakers want them to; at 102 minutes, this the rare film that I think would obviously benefit from being longer, to give us more space to sink into the location, possibly spending more than just one day there. Beyond this, Ly and his crew, most notably cinematographer Julien Poupard and editor Flora Volpelière, have elected to present the film in the most safe, even banal aesthetic register possible. And sure, "safe" means something different here than it would in an American blockbuster, but French-made movies about poor people have a formula just like anything else, and that formula involves shaky hand-held, lots of street noise in the background, cutting arrhythmically in the middle of lines of dialogue and often cutting from one angle of a person to another angle of the same person, and keeping the shot scale close enough that we start to feel slightly trapped with the subjects. It can be done well or poorly, and it's being done well in Les Misérables. But it looks, moves, and sounds exactly the way I assumed it would when all I knew was the logline.

Part of me wonders if that's even the point. 24 years after La Haine, nothing has changed in French society, so we need to have the same stories told the same way to underscore that. On the other hand, the sort of generic "European art cinema" vibe to the style makes me feel like that's a generous reading. Les Misérables has something it's very urgently eager to say, and it says it with furious passion; but dramatically and stylistically, it doesn't have the same radicalism as it preaches. And that does blunt the impact of its passion somewhat. Then again, Hugo's novel also packed radical messages into a bourgeois-friendly art form, so perhaps this is just part of the heritage of being Les Misérables.