Assassins' creed

A review requested by Kevin, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

It is entirely possible that Hero is the single most beautiful film of the 2000s. I'm not making that argument myself, you understand (how could I dare to cheat on The Fall like that?), but if someone was making that argument around me, I'd certainly nod along agreeably and compliment them on their good taste.

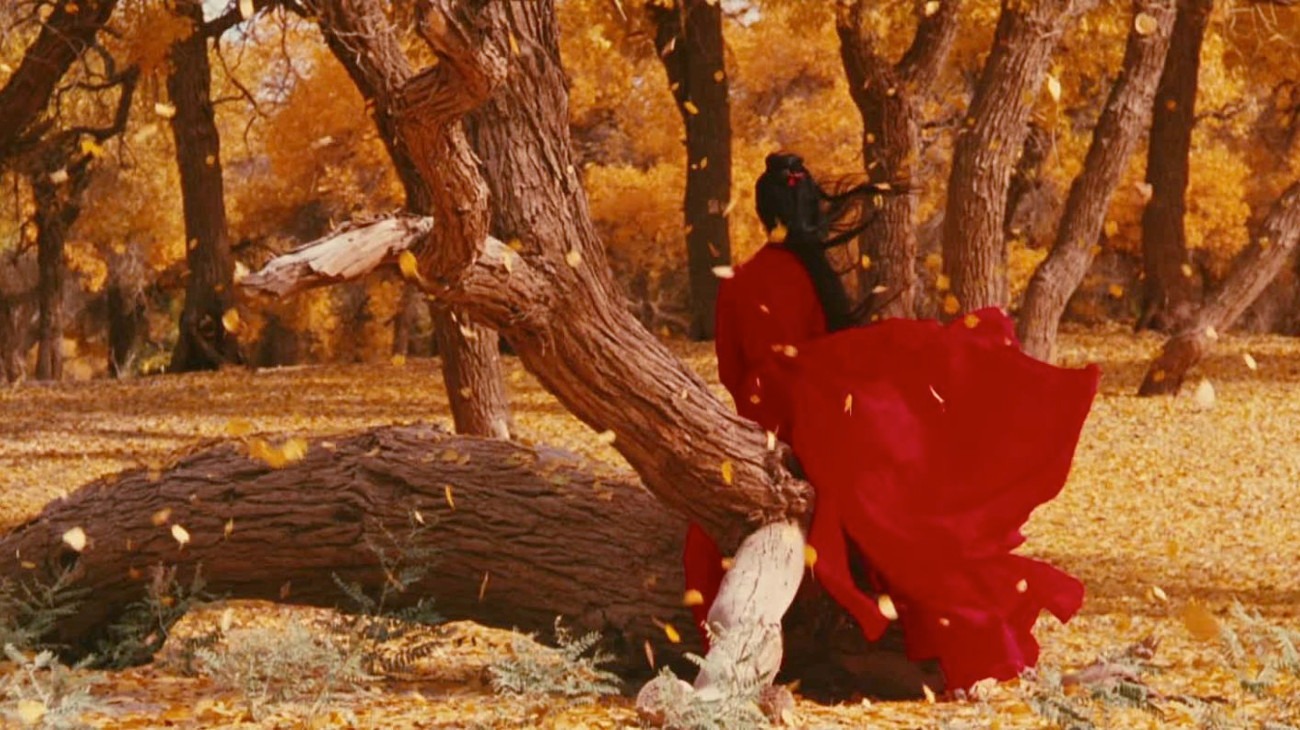

Director Zhang Yimou approached the film with a straightforward enough scheme: to take each chunk of the Rashomon-like collection of stories about what may have happened to three assassins during the 3rd Century BCE in what was not yet China, and color-code them. There is, very specifically, no greater theoretical meaning to which colors were used (though red is directly tied to blood in one of the most striking moments in the entire feature): just the Red Sequence, the Blue Sequence, the Black-and-White Sequence, the Yellow Sequence, the Grey Sequence, and green flashbacks scattered throughout. And each of these schemes is absolute. The costumes (designed by the great Wada Emi) are all solid blocks of saturated color, and the production design (by Huo Tingxiao and Yi Zhenzhou) is only slightly less complete in building rooms and outdoor spaces alike from only one or two primary shades. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle (working with Zhang for the only time) augments these colors by gently pushing the film in the direction of each color - not so much that it feels like the film has been tinted, but it's obviously the case that the humans onscreen are slightly flushed in the red sequence, slightly cool in the blue sequence, a little bit over-bright in the grey sequence.

It is a remarkable achievement, one that looks all the better all these years later, now that digital cinematography has won, and the ever-so-slightly smudgy, rich grain of the film stocks used in the different sequences makes this look like an artifact from a different civilisation. It's a very filmic film, Hero is, drawing as much attention to the physical medium on which it was shot as any other movie from the early 2000s that I can think of; maybe this is because of Doyle, whose work in the years before this project often tended to embrace the capacity of film to place a grainy veil between the viewer and the action (the enthusiastically smeary anarchic energy of 1994's Chungking Express obviously leaps to mind, along with the almost unbearably luxurious thickness of the images in 2000's In the Mood for Love). Maybe it's just because Hero calls so very much attention to how its images have been crafted through pure artifice, and that draws attention to the materiality of the production. Whatever the case, it's a lush, warm film, with the colors softly glowing off the screen.

The film is set near the very end of the Warring States period, shortly before King Zheng of Qin (Chen Daoming) became first Emperor of a unified China. It is a violent period, and there are many who would assassinate the king, so he has instituted extreme measures to keep himself safe: his royal chamber has been stripped of every decorative object except a cluster of candles, and no one may approach within 100 paces of him, under penalty of death. Unless, that is, the king himself permits a visitor to come nearer, as he does on the day that a nameless swordsman and prefect (Jet Li) arrives with news that he has killed the three assassins that were most tormenting the king's peace: Long Sky (Donnie Yen), Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung), and Broken Sword (Tony Leung Chiu-wai), as well as Broken Sword's pupil, Moon (Zhang Ziyi). Impressed, the king invites the nameless one to come close and tell his remarkable tale. But the king spots some irregularities in the story, and offers his own suspicious interpretation of events. The swordsman admits to the gaps in his story, but the king's version isn't correct either, so he explains the truth. And in so doing, the two men come to a shared understanding about the value of a unified China under a strong central leader.

So, unabashed pro-totalitarian propaganda? Yes. Maybe not unabashed - I am sure there have been readings motivated by finding the ways that Zhang, Li Feng, and Wang Bin suck in subversive hidden messages in this, and some of them are probably even persuasive. But it is certainly most obviously pro-totalitarian propaganda, and one is either going to be okay with that or one is not. Myself, I am much more fascinated by Chinese propaganda films than I was back in 2004, when Hero had its delayed release in the United States, and I just found the thing offensive. Frankly, I take Zhang at his word when he claims that he was more interested in creating an aesthetic experience than an intellectual one, for Hero is certainly a most aesthetically aggressive object. The ancient setting seems to have encouraged the filmmaker to go all the way with a fhighly formal approach to blocking and setting up the camera. It's a film full of precise geometry - and this is not a director known for loosey-goosey filmmaking prior to 2002 - that traps all of the characters in strong lines and bold compositions built around shapes: rectangles obviously, as seen very dramatically in the scenes with the king, but also circles, mostly associated with the the assassins. There are even a few astonishing triangular compositions, most notably a scene in which calligraphers are mowed down by arrows as they sit in unyielding diagonal lines staged recessionally away from the camera. In a film whose central theme is order emerging from anarchy, there's something appropriately unbending about the clean form (the color scheme is part of this too, for that matter)

The only time that this shifts at all is during the fight scenes. There are several of these, and honestly, the first one is the only one that's great as a fight scene. This is the fight between the swordsman and Long Sky: Li and Yen easily the two most accomplished martial artists in the main cast, so it's no surprise that the most elaborate choreography would be handed to them. It's not there's anything wrong with what follows, but given how much of a premium the film puts on extremes of style, one longs for more virtuoso fighting. Instead, most of what we see has the stately weightless quality of the wire-fu choreography that was so much in vogue at that moment. I have no idea if Hero, like 2000's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, was expressly made to bring wuxia to Western audiences, but I would be extremely unsurprised to learn that was the case: there's a similar feeling to how the fights play out. They're not virtuoso pieces, but elements in a robust epic framework that makes history feel mournfully heavy, in large part thanks to the help of a Tan Dun score that goes straight for European-style Romanticism (I realise as I write that, it doesn't sound like a compliment - it's meant to be).

Whatever the fights are doing, they frequently break away from the geometry of the rest of the compositions. This is especially true of one of the film's most deservedly iconic scenes, the face-off between Flying Snow and Moon in a pure yellow forest, where their movements are in gracefully formless spirals that accentuate the irregular lines of the forest itself. If the fight scenes end up feeling like they have a rich expressive power, this is mostly why: they break from the film and redirect its energies in a very visceral, ethereal way.

All of this speaks to Zhang's immense control over form, tone and structure; Hero is an immaculate movie, in a lot of ways. And now I have to grouse: is it too immaculate? This career created a fork in the director's career: before this, he'd mostly focused on stylistically lavish, psychologically-oriented character dramas, such as the masterpieces Raise the Red Lantern (1991) and To Live (1994). After this, he began to split his attention between character dramas and wuxia films, and of course there's no reason one couldn't do both. But for whatever reason, Zhang didn't seem to be great at it. His two biggest martial arts films in the West, Hero and 2004's House of Flying Daggers, are both quite weak on characterisation, compared to something like the slightly later Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles from 2005, and the road of action movies eventually took him all the way to 2016's The Great Wall, surely a contender for the worst film made by a master director in the 21st Century.

I don't want to talk about Hero like it's some kind of dramatically inert misfire, good for style and nothing else. It paints its characters are large-scale historical archetypes, and they work on this level. Also, the relationship between Flying Snow and Broken Sword, especially in the first, or "Red" sequence, benefits immensely from Cheung and Leung (only two years removed from sparking the best romantic tension in contemporary cinema in In the Mood for Love) being their to ground the friction between those characters in world-class acting, even if the roles aren't so complex that they need these actors - Flying Snow especially. The emotions are as self-consciously big as the characters and the setting: this isn't historical melodrama or historical romance, this is a full-on mythic epic, and it needs scale to match its generic broadness.

None of this is a problem with the film. I just find it a bit unsatisfying, is all. Crouching Tiger proved that you could hit this tone and still tell an incredibly rich, moving human story; there are decades' worth of wuxia epics prior to 2002 that demonstrate much the same thing, albeit with less conventional (to an American viewer) emotions being activated. Zhang was, and occasionally still is, so very great at crafting magnificent humans in overripe historical settings, it's a bit frustrating to see him step back to work in a self-consciously abstract mode like this, putting everything in boldface and deliberately distancing us from the material through the thickness of the form. I don't believe any bit of this is an error or an accident; it just leaves Hero feeling a bit chilly and impersonal, and that's a real disappointment from this of all directors.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

It is entirely possible that Hero is the single most beautiful film of the 2000s. I'm not making that argument myself, you understand (how could I dare to cheat on The Fall like that?), but if someone was making that argument around me, I'd certainly nod along agreeably and compliment them on their good taste.

Director Zhang Yimou approached the film with a straightforward enough scheme: to take each chunk of the Rashomon-like collection of stories about what may have happened to three assassins during the 3rd Century BCE in what was not yet China, and color-code them. There is, very specifically, no greater theoretical meaning to which colors were used (though red is directly tied to blood in one of the most striking moments in the entire feature): just the Red Sequence, the Blue Sequence, the Black-and-White Sequence, the Yellow Sequence, the Grey Sequence, and green flashbacks scattered throughout. And each of these schemes is absolute. The costumes (designed by the great Wada Emi) are all solid blocks of saturated color, and the production design (by Huo Tingxiao and Yi Zhenzhou) is only slightly less complete in building rooms and outdoor spaces alike from only one or two primary shades. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle (working with Zhang for the only time) augments these colors by gently pushing the film in the direction of each color - not so much that it feels like the film has been tinted, but it's obviously the case that the humans onscreen are slightly flushed in the red sequence, slightly cool in the blue sequence, a little bit over-bright in the grey sequence.

It is a remarkable achievement, one that looks all the better all these years later, now that digital cinematography has won, and the ever-so-slightly smudgy, rich grain of the film stocks used in the different sequences makes this look like an artifact from a different civilisation. It's a very filmic film, Hero is, drawing as much attention to the physical medium on which it was shot as any other movie from the early 2000s that I can think of; maybe this is because of Doyle, whose work in the years before this project often tended to embrace the capacity of film to place a grainy veil between the viewer and the action (the enthusiastically smeary anarchic energy of 1994's Chungking Express obviously leaps to mind, along with the almost unbearably luxurious thickness of the images in 2000's In the Mood for Love). Maybe it's just because Hero calls so very much attention to how its images have been crafted through pure artifice, and that draws attention to the materiality of the production. Whatever the case, it's a lush, warm film, with the colors softly glowing off the screen.

The film is set near the very end of the Warring States period, shortly before King Zheng of Qin (Chen Daoming) became first Emperor of a unified China. It is a violent period, and there are many who would assassinate the king, so he has instituted extreme measures to keep himself safe: his royal chamber has been stripped of every decorative object except a cluster of candles, and no one may approach within 100 paces of him, under penalty of death. Unless, that is, the king himself permits a visitor to come nearer, as he does on the day that a nameless swordsman and prefect (Jet Li) arrives with news that he has killed the three assassins that were most tormenting the king's peace: Long Sky (Donnie Yen), Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung), and Broken Sword (Tony Leung Chiu-wai), as well as Broken Sword's pupil, Moon (Zhang Ziyi). Impressed, the king invites the nameless one to come close and tell his remarkable tale. But the king spots some irregularities in the story, and offers his own suspicious interpretation of events. The swordsman admits to the gaps in his story, but the king's version isn't correct either, so he explains the truth. And in so doing, the two men come to a shared understanding about the value of a unified China under a strong central leader.

So, unabashed pro-totalitarian propaganda? Yes. Maybe not unabashed - I am sure there have been readings motivated by finding the ways that Zhang, Li Feng, and Wang Bin suck in subversive hidden messages in this, and some of them are probably even persuasive. But it is certainly most obviously pro-totalitarian propaganda, and one is either going to be okay with that or one is not. Myself, I am much more fascinated by Chinese propaganda films than I was back in 2004, when Hero had its delayed release in the United States, and I just found the thing offensive. Frankly, I take Zhang at his word when he claims that he was more interested in creating an aesthetic experience than an intellectual one, for Hero is certainly a most aesthetically aggressive object. The ancient setting seems to have encouraged the filmmaker to go all the way with a fhighly formal approach to blocking and setting up the camera. It's a film full of precise geometry - and this is not a director known for loosey-goosey filmmaking prior to 2002 - that traps all of the characters in strong lines and bold compositions built around shapes: rectangles obviously, as seen very dramatically in the scenes with the king, but also circles, mostly associated with the the assassins. There are even a few astonishing triangular compositions, most notably a scene in which calligraphers are mowed down by arrows as they sit in unyielding diagonal lines staged recessionally away from the camera. In a film whose central theme is order emerging from anarchy, there's something appropriately unbending about the clean form (the color scheme is part of this too, for that matter)

The only time that this shifts at all is during the fight scenes. There are several of these, and honestly, the first one is the only one that's great as a fight scene. This is the fight between the swordsman and Long Sky: Li and Yen easily the two most accomplished martial artists in the main cast, so it's no surprise that the most elaborate choreography would be handed to them. It's not there's anything wrong with what follows, but given how much of a premium the film puts on extremes of style, one longs for more virtuoso fighting. Instead, most of what we see has the stately weightless quality of the wire-fu choreography that was so much in vogue at that moment. I have no idea if Hero, like 2000's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, was expressly made to bring wuxia to Western audiences, but I would be extremely unsurprised to learn that was the case: there's a similar feeling to how the fights play out. They're not virtuoso pieces, but elements in a robust epic framework that makes history feel mournfully heavy, in large part thanks to the help of a Tan Dun score that goes straight for European-style Romanticism (I realise as I write that, it doesn't sound like a compliment - it's meant to be).

Whatever the fights are doing, they frequently break away from the geometry of the rest of the compositions. This is especially true of one of the film's most deservedly iconic scenes, the face-off between Flying Snow and Moon in a pure yellow forest, where their movements are in gracefully formless spirals that accentuate the irregular lines of the forest itself. If the fight scenes end up feeling like they have a rich expressive power, this is mostly why: they break from the film and redirect its energies in a very visceral, ethereal way.

All of this speaks to Zhang's immense control over form, tone and structure; Hero is an immaculate movie, in a lot of ways. And now I have to grouse: is it too immaculate? This career created a fork in the director's career: before this, he'd mostly focused on stylistically lavish, psychologically-oriented character dramas, such as the masterpieces Raise the Red Lantern (1991) and To Live (1994). After this, he began to split his attention between character dramas and wuxia films, and of course there's no reason one couldn't do both. But for whatever reason, Zhang didn't seem to be great at it. His two biggest martial arts films in the West, Hero and 2004's House of Flying Daggers, are both quite weak on characterisation, compared to something like the slightly later Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles from 2005, and the road of action movies eventually took him all the way to 2016's The Great Wall, surely a contender for the worst film made by a master director in the 21st Century.

I don't want to talk about Hero like it's some kind of dramatically inert misfire, good for style and nothing else. It paints its characters are large-scale historical archetypes, and they work on this level. Also, the relationship between Flying Snow and Broken Sword, especially in the first, or "Red" sequence, benefits immensely from Cheung and Leung (only two years removed from sparking the best romantic tension in contemporary cinema in In the Mood for Love) being their to ground the friction between those characters in world-class acting, even if the roles aren't so complex that they need these actors - Flying Snow especially. The emotions are as self-consciously big as the characters and the setting: this isn't historical melodrama or historical romance, this is a full-on mythic epic, and it needs scale to match its generic broadness.

None of this is a problem with the film. I just find it a bit unsatisfying, is all. Crouching Tiger proved that you could hit this tone and still tell an incredibly rich, moving human story; there are decades' worth of wuxia epics prior to 2002 that demonstrate much the same thing, albeit with less conventional (to an American viewer) emotions being activated. Zhang was, and occasionally still is, so very great at crafting magnificent humans in overripe historical settings, it's a bit frustrating to see him step back to work in a self-consciously abstract mode like this, putting everything in boldface and deliberately distancing us from the material through the thickness of the form. I don't believe any bit of this is an error or an accident; it just leaves Hero feeling a bit chilly and impersonal, and that's a real disappointment from this of all directors.