The horrible world of Doctor Dolittle

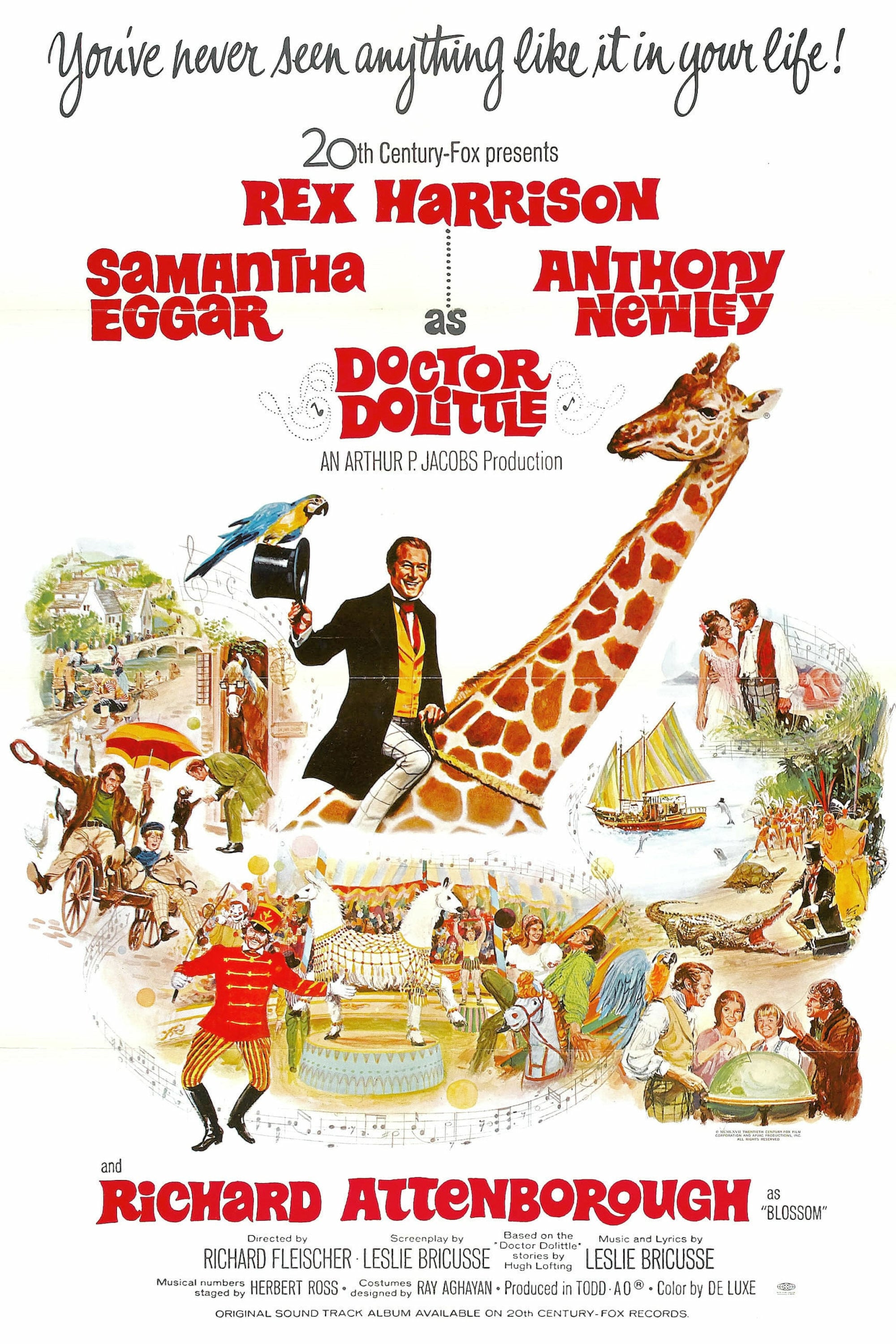

As of 18 January 2020, 563 films have been nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, and 1967's Doctor Dolittle is the worst one of them.

This is not, we must immediately make clear, an example of a film that's not very good that still got that nomination, and several others, because it was an undeniable Zeitgeist hit, or because it gave comfort to some small but vociferous minority of Oscar voters. Nobody liked Doctor Dolittle in 1967. Critics tore it apart. Audiences mostly stayed far away, making it a massive financial bomb that almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox, just two years after The Sound of Music had rescued them from the last time they were almost bankrupted, by Cleopatra. One of the most ambitious merchandising tie-in programs in Hollywood history ended with tens of millions of dollars' worth of Dolittle-themed gewgaws collecting dust on store shelves. The people who made it did not like it - the set was an infamous bog of hateful squabbling and complaining and general misery (this is the point where I inevitably mention Mark Harris's terrific 2008 history Pictures at a Revolution, which persuasively argues that the production of Doctor Dolittle was the most fascinating thing in the entire world of motion pictures in '66 and '67). The only reason it got any Oscar nominations at all was essentially because 20th Century Fox glared at the Academy and snarled, "we will be receiving a Best Picture nomination. In fact, nine nominations altogether, please", and the Academy had too much on its plate just then to bother fighting.

The film is one of the last giant-scale musicals of the 1960s, and in some ways, it feels like the summary of that subgenre. Specifically, it feels like the meeting point between 1964's Mary Poppins (it's an effects-driven fantasy movie based on a series of British children's books) and My Fair Lady (Rex Harrison plays a crochety old grump who softens over the course of the plot, and several of the Dolittle songs are obvious, almost 1-to-1 analogues for much better Lady songs) and 1965's The Sound of Music (it was produced by 20th Century Fox, the studio that most hungrily pursued success with this behemoth-scaled productions). The sluggish 152-minute version that was ultimately released was no less than the third cut, pared down from two even longer versions that test audiences didn't like; given how much of an ordeal it is for the filmmakers to fill two and a half hours, the mind reels to wonder what possibly could have been cut, but I imagine it was very expensive-looking. For being expensive-looking is pretty much all that Doctor Dolittle has to offer.

It's mostly set in the village of Puddleby-on-the-Marsh in 1845, and great effort was spent making the locations (and then the sets built to replace the locations when filming in the United Kingdom proved to be too much of an ordeal) feel as fussily storybook-like as the overstuffed interior sets, crammed with bric-a-brac, while also being shot without the stagey theatricality of some of the more happily artificial '60s musicals. I hesitate to use the word "realism", but there's a definite tactility to Doctor Dolittle, a sense of place; when we see Rex Harrison tromping through a field, it's real field, with real sunlight; when Samantha Eggar falls into a creek, she's really scrambling to get back out of it. There's a rich depth to the settings in Doctor Dolittle, a physicality that is probably the one single aspect of the film's aesthetic that actually works as cinema. So even if the money that 20th Century Fox dumped into the film was a monumental disaster of management, at least you can see it onscreen. Admittedly, it's filmed mostly in a series of sludgy browns by Robert Surtees (who also shot The Graduate, another 1967 Best Picture nominee, and it's baffling how much the story about impersonal suburban anomie is more vibrant-looking than the children's fantasy), but that somewhat lends it even more of a sense of realistic heft.

The story that takes place within this well-realised setting is a grueling nightmare. It took a great deal of effort to hew a narrative out of this material; in the end, Leslie Bricusse was responsible for the final draft, synthesizing the first three books of Hugh Lofting's Doctor Dolittle series into a malformed blob that feels like a constant act of deferment. Dr. John Dolittle (Harrison), a happy misanthrope who speaks several hundred animal languages and has thus dedicated himself to being England's foremost veterinarian, wants to find the legendary Great Pink Sea Snail, for unclear reasons. In order to do this, he needs to raise money to rent a boat, so we get an entire second act that involves him running a circus. The first act is just the "getting to know you" part. The third act finally sets him on that boat. It is impossible to overstate how disjointed these three pieces feel; Mary Poppins has a similarly difficult time making a single narrative out of its source material, but that at least feels genuinely episodic, like a mosaic where every small piece builds to a whole. Doctor Dolittle feels like an entire movie trilogy of unrelated tales crammed into one body, and somehow, every individual third of it is the worst part.

The failures on display are legion, so many that it's hard to know where to start. The casting is abysmal, for a start. While Harrison was part of the project from early on, he's a godawful Dolittle; the character as written is a colorful eccentric, but Harrison, unsurprisingly, plays him as a smug know-it-all, delighted to have friends only so he can show off his knowledge. It's an unlikable smarmy, egocentric vision of the doctor as somebody that no-one in their right mind could stand to be around for more than a few minutes at a stretch, and we get so spend our whole evening with him. Anthony Newley, playing the lackadaisical and extremely Irish meat salesman Matthew Mugg, Dolittle's best human friend, does a fantastic job of hiding his extreme disdain for his co-star (Harrison amused himself by spending the whole shoot baiting Newley with anti-Semitic slurs), but that's the only thing he's fantastic at: his Irish accent is garish and tacky, his ambling way of falling through sets charmless, his attempts to flirt with Eggar's character veering into lechery. Eggar herself is buried by a part that's only barely conceived, and unlike Newley, she's not good at pretending that she feels anything but revulsion for Harrison.

The film also has appalling songs - also by Bricusse, working for the first time as a solo act (he'd previously written the stage musicals Stop the World - I Want to Get Off and The Roar of the Greasepaint - The Smell of the Crowd with Newley, and Pickwick with Cyril Ornadel). Bricusse was more of a lyricist than a composer, which is obvious from every last number in Doctor Dolittle, almost all of which have cluttered, over-written lyrics and simple, march-like melodies that let everybody engage in the flat speak-singing that Harrison used in My Fair Lady. Perhaps to compensate, he goes all the way from "speaking-singing" to just plain "speaking"; the film's signature song, "Talk to the Animals", finds him basically just reciting poetry as the music mindlessly jangles out behind him. And good God, such irritating poetry! Bricusse has a tic on display all throughout Doctor Dolittle that's most overt in "Talk to the Animals", of burying extremely clever rhymes inside lines, so we get things like:

"Imagine talking to a tiger/

Chatting with a cheetah/

What a neat a-/

-chievement that would be".

Sometimes, it's merely labored wordplay:

"If friends say, 'can he talk in crab or pelican?'/

You'll say, 'like hell 'e can'/

And you'll be right"

-which suggests either that the phrase "like hell he can" means something different in American and British English, or that Bricusse was so concerned with cunning rhymes that he was willing to sacrifice meaning for it. The latter of which certainly happens all throughout the movie. For this, Bricusse won a Best Original Song Oscar in the year that "The Bare Necessities" from The Jungle Book and "The Look of Love" from Casino Royale were also nominated.

It took, I am sure, tremendously hard work for Bricusse to come up with the intricate, fussy rhymes that are used all through Doctor Dolittle, so I don't want to slag the effort involved. But I don't know that anybody has ever said "that was such effortful rhyming!" and intended it as a compliment. The songs in Doctor Dolittle are frankly exhausting to listen to, so endlessly eager to make sure we notice that they are extremely clever that they insistently push us into a highly alert mental state that's in no way worth the meager payoff.

The musical numbers set to those songs are no better. Richard Fleischer was director given to heavy, obvious staging in almost everything he ever made, and this is brutally bad for a musical, especially one that's already as heavy as this. Several of the numbers just involve people standing and singing in each other's faces, especially the endless "Fabulous Places", where all four of the leads (I have not mentioned the fourth: wide-eyed child Tommy Stubbins, played by William Dix) take turns using Bricusse's brittle rhymes to talk about the locations they'd most like to travel to. Sometimes they involve walking through the busy sets, as in the introductory "My Friend the Doctor", which is probably the best part of the film, on the grounds that the walking is done by Anthony Newley with great energy, the camera moves, and the song comes close enough to plagiarising "Maria" from The Sound of Music that it almost sounds good. Sometimes, it just involves cutting from one scene of Harrison striking a pose to another, in an endless chain of dissociated shots evacuated of all meaning, as in "If I Could Talk to the God-Damn Animals". At its very worst, it ends in the sprawling disorder "I've Never Seen Anything Like It", which has, on the one hand, the worst lyrics in the film:

"I'm not a fool/

I went to school/

I've been from Liverpool to Istanbul/

Istanbul/

I'm no fool"

And on the other hand, the worst choreography, obliging Richard Attenborough to do this horrible thing where he walks by kicking his legs really far forward and kind of bouncing along in a sort of martial skipping - I imagine it's something from a British music hall tradition, but it looks like a Nazi rally staged by the Rockettes. Also, Attenborough keeps bellowing "I've never seen anything like it!" like he's trying to cough up a lung.

The songs are the joyless low points of a film that has no heights. Its fantasy is threadbare (the Great Pink Sea Snail looks like it would crumple in a stiff wind), its humor is mirthless, its characters unlikable, its themes incoherent. Its two and a half hours move by without a trace of momentum or any sense that we're building up to anything, and given how much of a shrug the last few minutes are, that sense is exactly right. All it has is the illusion of prestige grafted onto it by costing far too much money, and some hellacious-sounding behind-the-scenes stories. It is a dirge, the nadir of '60s big-budget filmmaking, and I even appreciate that it got all those Oscar nominations, if only on the grounds that this is the most unlikable extreme of what Oscarbait cinema can look like, and I'm pleased to know that the industry and the Academy don't have the luxury of running away from it.

This is not, we must immediately make clear, an example of a film that's not very good that still got that nomination, and several others, because it was an undeniable Zeitgeist hit, or because it gave comfort to some small but vociferous minority of Oscar voters. Nobody liked Doctor Dolittle in 1967. Critics tore it apart. Audiences mostly stayed far away, making it a massive financial bomb that almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox, just two years after The Sound of Music had rescued them from the last time they were almost bankrupted, by Cleopatra. One of the most ambitious merchandising tie-in programs in Hollywood history ended with tens of millions of dollars' worth of Dolittle-themed gewgaws collecting dust on store shelves. The people who made it did not like it - the set was an infamous bog of hateful squabbling and complaining and general misery (this is the point where I inevitably mention Mark Harris's terrific 2008 history Pictures at a Revolution, which persuasively argues that the production of Doctor Dolittle was the most fascinating thing in the entire world of motion pictures in '66 and '67). The only reason it got any Oscar nominations at all was essentially because 20th Century Fox glared at the Academy and snarled, "we will be receiving a Best Picture nomination. In fact, nine nominations altogether, please", and the Academy had too much on its plate just then to bother fighting.

The film is one of the last giant-scale musicals of the 1960s, and in some ways, it feels like the summary of that subgenre. Specifically, it feels like the meeting point between 1964's Mary Poppins (it's an effects-driven fantasy movie based on a series of British children's books) and My Fair Lady (Rex Harrison plays a crochety old grump who softens over the course of the plot, and several of the Dolittle songs are obvious, almost 1-to-1 analogues for much better Lady songs) and 1965's The Sound of Music (it was produced by 20th Century Fox, the studio that most hungrily pursued success with this behemoth-scaled productions). The sluggish 152-minute version that was ultimately released was no less than the third cut, pared down from two even longer versions that test audiences didn't like; given how much of an ordeal it is for the filmmakers to fill two and a half hours, the mind reels to wonder what possibly could have been cut, but I imagine it was very expensive-looking. For being expensive-looking is pretty much all that Doctor Dolittle has to offer.

It's mostly set in the village of Puddleby-on-the-Marsh in 1845, and great effort was spent making the locations (and then the sets built to replace the locations when filming in the United Kingdom proved to be too much of an ordeal) feel as fussily storybook-like as the overstuffed interior sets, crammed with bric-a-brac, while also being shot without the stagey theatricality of some of the more happily artificial '60s musicals. I hesitate to use the word "realism", but there's a definite tactility to Doctor Dolittle, a sense of place; when we see Rex Harrison tromping through a field, it's real field, with real sunlight; when Samantha Eggar falls into a creek, she's really scrambling to get back out of it. There's a rich depth to the settings in Doctor Dolittle, a physicality that is probably the one single aspect of the film's aesthetic that actually works as cinema. So even if the money that 20th Century Fox dumped into the film was a monumental disaster of management, at least you can see it onscreen. Admittedly, it's filmed mostly in a series of sludgy browns by Robert Surtees (who also shot The Graduate, another 1967 Best Picture nominee, and it's baffling how much the story about impersonal suburban anomie is more vibrant-looking than the children's fantasy), but that somewhat lends it even more of a sense of realistic heft.

The story that takes place within this well-realised setting is a grueling nightmare. It took a great deal of effort to hew a narrative out of this material; in the end, Leslie Bricusse was responsible for the final draft, synthesizing the first three books of Hugh Lofting's Doctor Dolittle series into a malformed blob that feels like a constant act of deferment. Dr. John Dolittle (Harrison), a happy misanthrope who speaks several hundred animal languages and has thus dedicated himself to being England's foremost veterinarian, wants to find the legendary Great Pink Sea Snail, for unclear reasons. In order to do this, he needs to raise money to rent a boat, so we get an entire second act that involves him running a circus. The first act is just the "getting to know you" part. The third act finally sets him on that boat. It is impossible to overstate how disjointed these three pieces feel; Mary Poppins has a similarly difficult time making a single narrative out of its source material, but that at least feels genuinely episodic, like a mosaic where every small piece builds to a whole. Doctor Dolittle feels like an entire movie trilogy of unrelated tales crammed into one body, and somehow, every individual third of it is the worst part.

The failures on display are legion, so many that it's hard to know where to start. The casting is abysmal, for a start. While Harrison was part of the project from early on, he's a godawful Dolittle; the character as written is a colorful eccentric, but Harrison, unsurprisingly, plays him as a smug know-it-all, delighted to have friends only so he can show off his knowledge. It's an unlikable smarmy, egocentric vision of the doctor as somebody that no-one in their right mind could stand to be around for more than a few minutes at a stretch, and we get so spend our whole evening with him. Anthony Newley, playing the lackadaisical and extremely Irish meat salesman Matthew Mugg, Dolittle's best human friend, does a fantastic job of hiding his extreme disdain for his co-star (Harrison amused himself by spending the whole shoot baiting Newley with anti-Semitic slurs), but that's the only thing he's fantastic at: his Irish accent is garish and tacky, his ambling way of falling through sets charmless, his attempts to flirt with Eggar's character veering into lechery. Eggar herself is buried by a part that's only barely conceived, and unlike Newley, she's not good at pretending that she feels anything but revulsion for Harrison.

The film also has appalling songs - also by Bricusse, working for the first time as a solo act (he'd previously written the stage musicals Stop the World - I Want to Get Off and The Roar of the Greasepaint - The Smell of the Crowd with Newley, and Pickwick with Cyril Ornadel). Bricusse was more of a lyricist than a composer, which is obvious from every last number in Doctor Dolittle, almost all of which have cluttered, over-written lyrics and simple, march-like melodies that let everybody engage in the flat speak-singing that Harrison used in My Fair Lady. Perhaps to compensate, he goes all the way from "speaking-singing" to just plain "speaking"; the film's signature song, "Talk to the Animals", finds him basically just reciting poetry as the music mindlessly jangles out behind him. And good God, such irritating poetry! Bricusse has a tic on display all throughout Doctor Dolittle that's most overt in "Talk to the Animals", of burying extremely clever rhymes inside lines, so we get things like:

"Imagine talking to a tiger/

Chatting with a cheetah/

What a neat a-/

-chievement that would be".

Sometimes, it's merely labored wordplay:

"If friends say, 'can he talk in crab or pelican?'/

You'll say, 'like hell 'e can'/

And you'll be right"

-which suggests either that the phrase "like hell he can" means something different in American and British English, or that Bricusse was so concerned with cunning rhymes that he was willing to sacrifice meaning for it. The latter of which certainly happens all throughout the movie. For this, Bricusse won a Best Original Song Oscar in the year that "The Bare Necessities" from The Jungle Book and "The Look of Love" from Casino Royale were also nominated.

It took, I am sure, tremendously hard work for Bricusse to come up with the intricate, fussy rhymes that are used all through Doctor Dolittle, so I don't want to slag the effort involved. But I don't know that anybody has ever said "that was such effortful rhyming!" and intended it as a compliment. The songs in Doctor Dolittle are frankly exhausting to listen to, so endlessly eager to make sure we notice that they are extremely clever that they insistently push us into a highly alert mental state that's in no way worth the meager payoff.

The musical numbers set to those songs are no better. Richard Fleischer was director given to heavy, obvious staging in almost everything he ever made, and this is brutally bad for a musical, especially one that's already as heavy as this. Several of the numbers just involve people standing and singing in each other's faces, especially the endless "Fabulous Places", where all four of the leads (I have not mentioned the fourth: wide-eyed child Tommy Stubbins, played by William Dix) take turns using Bricusse's brittle rhymes to talk about the locations they'd most like to travel to. Sometimes they involve walking through the busy sets, as in the introductory "My Friend the Doctor", which is probably the best part of the film, on the grounds that the walking is done by Anthony Newley with great energy, the camera moves, and the song comes close enough to plagiarising "Maria" from The Sound of Music that it almost sounds good. Sometimes, it just involves cutting from one scene of Harrison striking a pose to another, in an endless chain of dissociated shots evacuated of all meaning, as in "If I Could Talk to the God-Damn Animals". At its very worst, it ends in the sprawling disorder "I've Never Seen Anything Like It", which has, on the one hand, the worst lyrics in the film:

"I'm not a fool/

I went to school/

I've been from Liverpool to Istanbul/

Istanbul/

I'm no fool"

And on the other hand, the worst choreography, obliging Richard Attenborough to do this horrible thing where he walks by kicking his legs really far forward and kind of bouncing along in a sort of martial skipping - I imagine it's something from a British music hall tradition, but it looks like a Nazi rally staged by the Rockettes. Also, Attenborough keeps bellowing "I've never seen anything like it!" like he's trying to cough up a lung.

The songs are the joyless low points of a film that has no heights. Its fantasy is threadbare (the Great Pink Sea Snail looks like it would crumple in a stiff wind), its humor is mirthless, its characters unlikable, its themes incoherent. Its two and a half hours move by without a trace of momentum or any sense that we're building up to anything, and given how much of a shrug the last few minutes are, that sense is exactly right. All it has is the illusion of prestige grafted onto it by costing far too much money, and some hellacious-sounding behind-the-scenes stories. It is a dirge, the nadir of '60s big-budget filmmaking, and I even appreciate that it got all those Oscar nominations, if only on the grounds that this is the most unlikable extreme of what Oscarbait cinema can look like, and I'm pleased to know that the industry and the Academy don't have the luxury of running away from it.

Categories: adventure, comedies, costume dramas, crimes against art, fantasy, musicals, needless adaptations, oscarbait