Amongst women

There's only one actually useful thing that art critics can ever do, which is to celebrate the small and underseen, to do whatever it is in our power to make very special work find an audience it otherwise wouldn't have. In that spirit, I would like to suggest that if you take one piece of advice I've offered in 2019 to heart, it's this: watch The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open. It's a movie you probably haven't heard of (I wouldn't have, if not for haunting Nick Davis's 2019 diary - see, critics matter), but you don't even have to pay or hunt for it: it's streaming on Netflix, in the United States at least, as part of the streaming service's arrangement with ARRAY, the company Ava DuVernay founded to help distribute movies by members of marginalised communities. Even as I'm glad that the film exists in a readily-watchable form, I do regret that Netflix is the only way to catch it: this is a commanding work of cinema, one of the year's most acute examples of casual, everyday naturalism being used to serve a drama of ideas, rather than just to reflexively assure us that this is what real life really is, man. And it's also 2019's second-best example of the profound possibilities of long-take filmmaking, right behind Bi Gan's Long Day's Journey into Night and a distinct bit ahead of Sam Mendes's effortful 1917.

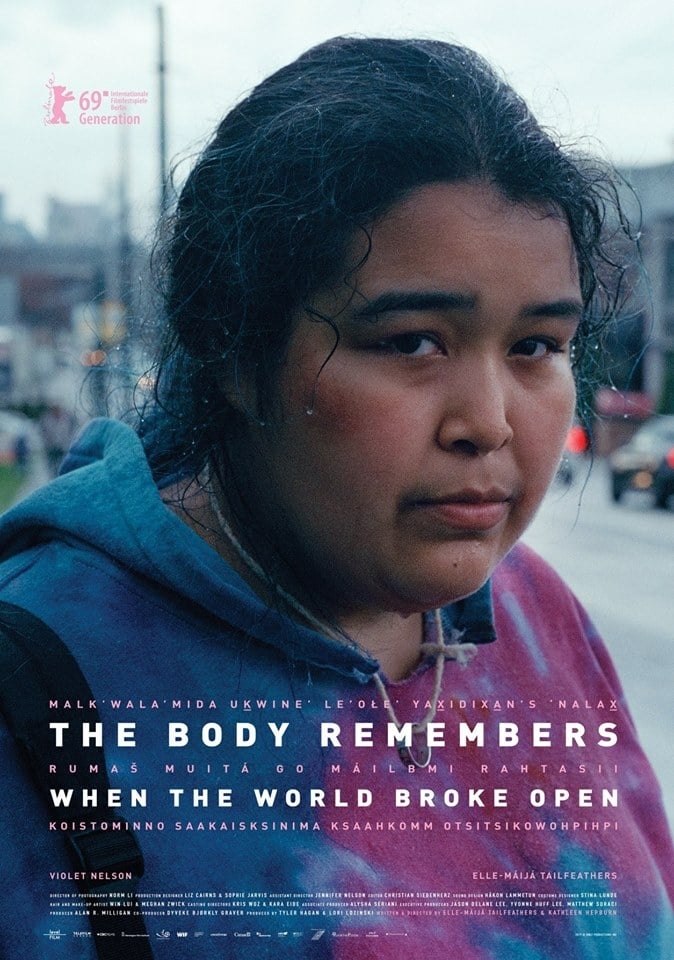

It's a kind of message movie about domestic violence, which is the thing that makes it hard to recommend, of course. The heart of the film is a long conversation in multiple locations between Áila (Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers), a middle-class half-Blackfoot, half-Sámi woman, and Rosie (Violet Nelson), a much lower-class First Nations woman; the conversation starts when Áila meets Rosie standing barefoot in a rainy street, having just run out of her house while being physically beaten by her boyfriend. This isn't where the film starts; we've already met both women, and have been given a good sense of how their very different lives function. But this is the point where the film shifts to a single take (or the illusion of one crafted from 12 different reels of 16mm film) that follows Áila's efforts to bring Rosie to an anonymous safe house for the victims of domestic violence, with Rosie's persistently begrudging, hostile acquiescence.

The long take isn't an incidental part of what this film is doing and why: this is one of the year's most elegant marriages of style and content. Among the many topics the film touches on, one of the most persistent is the idea that nobody can make another person do the right thing, particularly when "the right thing" is a contingent thing that people can and will disagree about. For Áila, the best course of action for Rosie is obvious, and in order to convince her to take it, she spends the great majority of the film's 106 minutes delicately nudging. The extraordinary long take is, in some sense, nothing but the formal equivalent to Áila's conversation: something that has to be done very carefully for over an hour, and if at any point you fuck it up, you have to go all the way back to the start. The unblinking presence of the camera thus feeds an incredible tension into the conversation, making every single line feel weighted with unimaginable consequence, even though the dialogue is all pointedly shapeless and realistic; in the case of Rosie, much of it barely registers as dialogue at all. Simply by virtue of trapping us in the eternal present of that room with those characters as they talk past each other, The Body Remembers makes their conversation the most desperately important thing you could imagine.

And part of the point is that we should take it to be just exactly that. The film touches on many topics, I have said, but most of them are related in some way to the problems of communicating across barriers, and the desperately hard matter of building solidarity. Basically, the two characters each view their interaction from two incompatible perspectives: for Áila, this is about women bonding and helping each other in the face of gendered violence, while for Rosie, this is about a half-white woman with a nice home and easy access to all the resources she needs smugly informing her social inferior about the proper way to behave. The film balances these perspectives with utmost delicacy, though when it skews either way, it generally skews towards Rosie; in the occasions that the camera follows only one of them, rather than pulling back to a wider shot to keep them both in frame, it usually follows her. In so doing, it turns Áila into an off-camera presence who feels a bit distant and detached: in one particularly potent scene, we hear her calling the shelter while Rosie watches with an impassive expression; something about the composition, the off-screen sound, and Nelson's performance combine to make Áila feel just very presumptuous, even if we've encountered Rosie alongside her, seen her bruises, and very likely (given the demographics of people who watch punishingly sad art films) had the same patronising "oh, dear, you must let us help you" response. On the other hand, the film absolutely wants Rosie to end up in that shelter, and every moment when she resists is heart-stopping. So, again. Balance.

It is an immaculate construct that writer-directors Tailfeathers (who apparently experienced something akin to the situation her character lives through here) and Kathleen Hepburn have assembled here. The whole movie works as a series of compare/contrasts, from the narrative situations and mise en scène to the way that the two leads perform their characters: Tailfeathers is crisp and precise, with well-defined blocking, while Nelson mumbles words in a monotone as she holds long still poses and does most of her work through facial expressions. They're both consummate screen performances, though Nelson's knocked me much flatter, both because of the much higher degree of difficulty (she is creating a character whose actions and words are designed to lead the other characters, and thus us, away from learning who she is, how she feels, and what she's thinking; but we also have to actually figure out how she feels and what she's thinking), and because her low-energy naturalism seems so much more lived-in and organic.

It also probably helps that she avoids most of the film's most aggravating flaw: the dialogue feels like it's being delivered by people who know that they're characters in a message movie about the importance of women's shelters, stiff and expository and rhetorically pushy. And you could probably argue that there are good thematic reasons for Áila to talk like a character in a message movie while Rosie talks like a character from an '80s indie movie, but I don't actually know that the film intends them; it seems to want very much for these to both be extremely well-defined human figures. And to be sure, it gets about 90% of the way there. This is an exquisitely felt human drama, situated in such an exact corner of Vancouver populated by such a distinct culture that it feels like it could only possibly happen to precisely these two women, and it is exactly because of that specificity that it has the emotional depth to feel wholly universal in the problems it dissects and the message it tells.

It's a kind of message movie about domestic violence, which is the thing that makes it hard to recommend, of course. The heart of the film is a long conversation in multiple locations between Áila (Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers), a middle-class half-Blackfoot, half-Sámi woman, and Rosie (Violet Nelson), a much lower-class First Nations woman; the conversation starts when Áila meets Rosie standing barefoot in a rainy street, having just run out of her house while being physically beaten by her boyfriend. This isn't where the film starts; we've already met both women, and have been given a good sense of how their very different lives function. But this is the point where the film shifts to a single take (or the illusion of one crafted from 12 different reels of 16mm film) that follows Áila's efforts to bring Rosie to an anonymous safe house for the victims of domestic violence, with Rosie's persistently begrudging, hostile acquiescence.

The long take isn't an incidental part of what this film is doing and why: this is one of the year's most elegant marriages of style and content. Among the many topics the film touches on, one of the most persistent is the idea that nobody can make another person do the right thing, particularly when "the right thing" is a contingent thing that people can and will disagree about. For Áila, the best course of action for Rosie is obvious, and in order to convince her to take it, she spends the great majority of the film's 106 minutes delicately nudging. The extraordinary long take is, in some sense, nothing but the formal equivalent to Áila's conversation: something that has to be done very carefully for over an hour, and if at any point you fuck it up, you have to go all the way back to the start. The unblinking presence of the camera thus feeds an incredible tension into the conversation, making every single line feel weighted with unimaginable consequence, even though the dialogue is all pointedly shapeless and realistic; in the case of Rosie, much of it barely registers as dialogue at all. Simply by virtue of trapping us in the eternal present of that room with those characters as they talk past each other, The Body Remembers makes their conversation the most desperately important thing you could imagine.

And part of the point is that we should take it to be just exactly that. The film touches on many topics, I have said, but most of them are related in some way to the problems of communicating across barriers, and the desperately hard matter of building solidarity. Basically, the two characters each view their interaction from two incompatible perspectives: for Áila, this is about women bonding and helping each other in the face of gendered violence, while for Rosie, this is about a half-white woman with a nice home and easy access to all the resources she needs smugly informing her social inferior about the proper way to behave. The film balances these perspectives with utmost delicacy, though when it skews either way, it generally skews towards Rosie; in the occasions that the camera follows only one of them, rather than pulling back to a wider shot to keep them both in frame, it usually follows her. In so doing, it turns Áila into an off-camera presence who feels a bit distant and detached: in one particularly potent scene, we hear her calling the shelter while Rosie watches with an impassive expression; something about the composition, the off-screen sound, and Nelson's performance combine to make Áila feel just very presumptuous, even if we've encountered Rosie alongside her, seen her bruises, and very likely (given the demographics of people who watch punishingly sad art films) had the same patronising "oh, dear, you must let us help you" response. On the other hand, the film absolutely wants Rosie to end up in that shelter, and every moment when she resists is heart-stopping. So, again. Balance.

It is an immaculate construct that writer-directors Tailfeathers (who apparently experienced something akin to the situation her character lives through here) and Kathleen Hepburn have assembled here. The whole movie works as a series of compare/contrasts, from the narrative situations and mise en scène to the way that the two leads perform their characters: Tailfeathers is crisp and precise, with well-defined blocking, while Nelson mumbles words in a monotone as she holds long still poses and does most of her work through facial expressions. They're both consummate screen performances, though Nelson's knocked me much flatter, both because of the much higher degree of difficulty (she is creating a character whose actions and words are designed to lead the other characters, and thus us, away from learning who she is, how she feels, and what she's thinking; but we also have to actually figure out how she feels and what she's thinking), and because her low-energy naturalism seems so much more lived-in and organic.

It also probably helps that she avoids most of the film's most aggravating flaw: the dialogue feels like it's being delivered by people who know that they're characters in a message movie about the importance of women's shelters, stiff and expository and rhetorically pushy. And you could probably argue that there are good thematic reasons for Áila to talk like a character in a message movie while Rosie talks like a character from an '80s indie movie, but I don't actually know that the film intends them; it seems to want very much for these to both be extremely well-defined human figures. And to be sure, it gets about 90% of the way there. This is an exquisitely felt human drama, situated in such an exact corner of Vancouver populated by such a distinct culture that it feels like it could only possibly happen to precisely these two women, and it is exactly because of that specificity that it has the emotional depth to feel wholly universal in the problems it dissects and the message it tells.