Local hero

Clint Eastwood, a director I have admired and enjoyed far more often than not, has always had two pronounced weaknesses. One is that he directs like an actor, famously remaining hands-off and letting his cast find their characters, while using few takes to avoid draining their freshness. And this only works with a certain kind of actor, which is why the non-actors in his films are almost always awful, while even some of the professionals can seem a bit stuck. The other is that he is powerless in the face of his screenplay: when the writing is good, or even just solid, he can get some fantastic things out of it, but if there are significant problems with the structure or characterisations, he folds up completely.

I bring these flaws not to complain, but to celebrate their absence: Richard Jewell, his 38th feature as director (one always itches to add "and perhaps his last" to everything the 89-year-old touches, but I will live in hope), is perhaps his first film of the 2010s that suffers from neither of those two flaws. There's one performance that needed more time in the oven, and a final scene that would have been better-served by a bland expository title card (and I say this as someone for whom expository title cards are not a small reason that I detest biopics), among other small writing fuck-ups, but overall this is material that plays atypically well to Eastwood's strengths, enough for me to call it with only a little hesitation his best film since Letters from Iwo Jima in 2006 (which I expect will remain the terminal point in all "Clint's best film since ____" conversations no matter how much longer he works). This is especially a nice treat coming after such a wildly uneven decade, especially given that we're not two full years removed from the wholly unforgivable The 15:17 to Paris, the kind of film that not even a lifelong Clint Eastwood apologist could possibly find a way to apologise for.

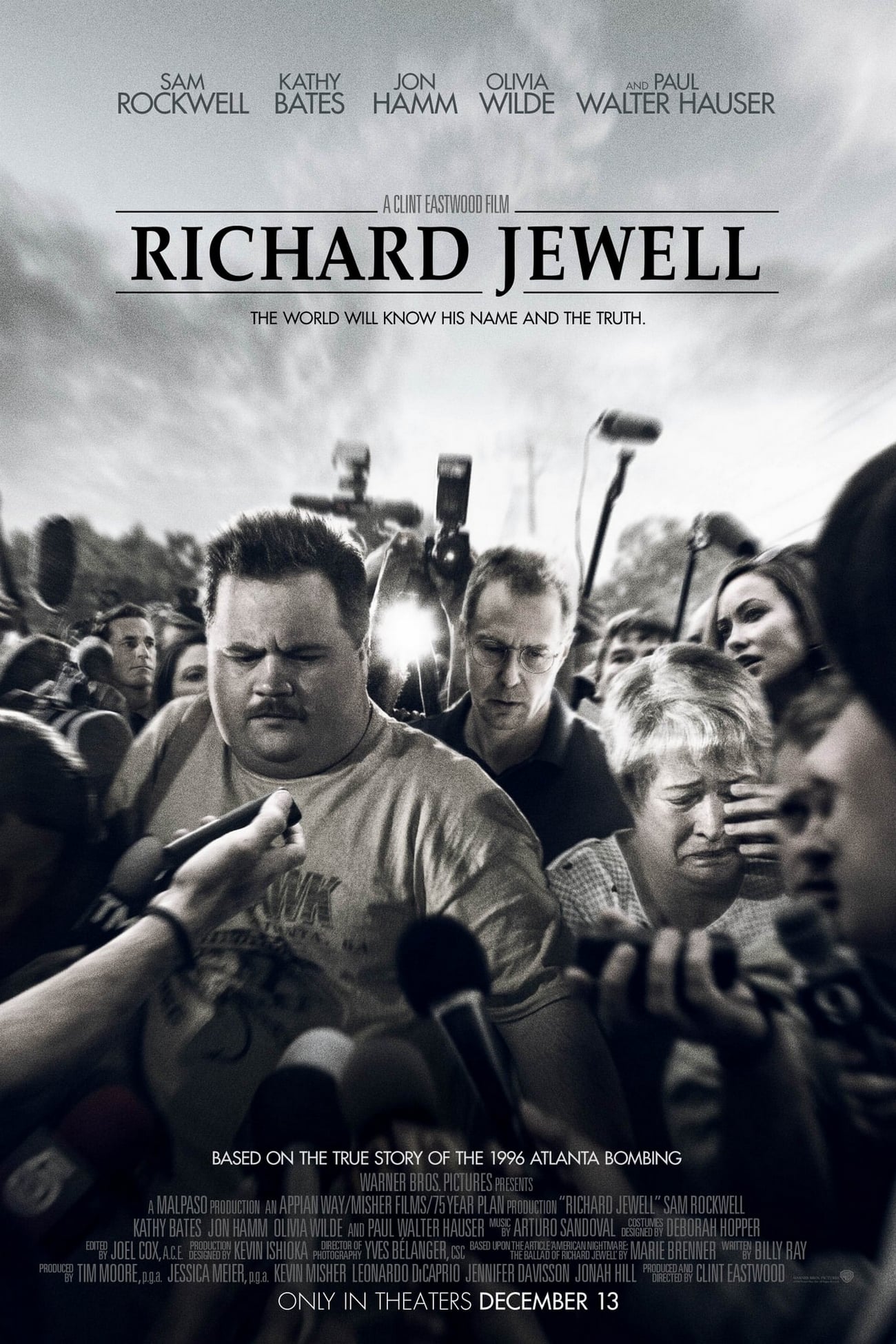

Richard Jewell is, you'll be shocked to hear, the story of Richard Jewell (Paul Walter Hauser), a wannabe cop who can't find anything closer than being an overbearing security guard in his home town of Atlanta. In this capacity, in 1996, he ended up working at Centennial Park during the Summer Olympics, where his paranoia paid off when he spotted a suspicious backpack that turned out to be a homemade pipe bomb. For a few days, he was celebrated in the national spotlight as a hero, before word got out that the FBI was investigating him for the crime, at which point he became a national villain and punchline. This movie, adapted by Billy Ray from an article and book about the events of that summer, functions mostly as an attempt to apologise to him for the extravagant speed with which he went from being praised to screamed at. For this would most likely have fucked with the head of anybody; given that Jewell was (if the film is right) already a bit of a broken, unstable person, it fucked with his head a lot.

That's the first strength of many: this isn't anything like a hagiography. Ray, Eastwood, and Hauser are very open in presenting Richard as an unlikable and pathetic figure. The first we see him, he's an office functionary at the Small Business Administration with creepy boundary issues, trying to impress lawyer Watson Bryant (Sam Rockwell, calming down and just giving a human-scale performance for the first time in what feels like years) by getting way too far into the other man's space. Even though Watson eventually decides to find this amusing rather than unsettling, first impressions in movies like life are lasting impressions, and Richard seems no less of an off-putting sad sack as we get to know him better: his groveling, insipid way of talking to anyone in law enforcement, in particular, is so irritating that the other sympathetic characters in the film all take him to task for it. He's awfully cringe-inducing for a hero, with his one great moment coming not because he's observant, but because he's dysfunctionally neurotic, and can't let go of the idea that every backpack hides a bomb; this one time, he just so happens to be right.

Having a prickly, uncomfortable protagonist like this probably isn't in and of itself enough to make Richard Jewell a good movie, but given the great psychological flattening that has afflicted so much of Oscarbait cinema in the 2010s, I'll take it. Especially given Hauser's performance, one of the year's best: his Richard is a quiet, shuffling bear of a man, awkward in his own body (Hauser nails the way that an insecure overweight man tries to direct attention away from himself by looking down and talking softly), keenly observant in ways that are a bit nerve-wracking to watch, given that he also seems (seems) to be very bad at understanding the things that he's observing, and so we're always waiting for this or that shoe to drop. The slight gradations in how he plays the character when he's comfortable with his scene partners - as he is with Kathy Bates, playing his mother, and doing a very fine job with a very functional role - versus when he's trying to wheedle and impress them is slightly heartbreaking, and its payoff near the end of the film is one of the most satisfying character beats in an Eastwood film in a very long time. The whole thing is more interested in characters than their actions, really, which is unusual for this filmmaker, but the fascination in watching people thinking and being is pervasive: there's a scene of people just hanging out and enjoying Kenny Rogers that is, in a very soft way, one of the most humane things in any Eastwood film, and even the designated villains - FBI Agent Tom Shaw (Jon Hamm) and journalist Kathy Scruggs (Olivia Wilde, the film's sole example of an actor who needed something Eastwood wasn't providing; she's chomping into the dialogue with a lot more melodramatic zeal than anything else in the film) - are still looked at with an interest that's less about their function in the plot than simply trying to figure out how they work and think.

This is overtly a Republican-facing message movie, but the most satisfying parts of the film have nothing to do with the message, and are far more elemental. This is basically a Kafkaesque fable about a man who has spent his whole life trying to be affable and abiding by the rules being plunged into a system where the nicer he tries to be, the worse he makes it for himself. The cinematography, by Yves Bélanger, is too soft and fuzzy, and the cutting, by Eastwood regular Joel Cox, is too devoid of urgency to honestly suggest that this has the tension necessary to qualify as a thriller, but that's where a lot of the plot and much of the acting suggests we are: a dive into an inexplicable terror at ever-escalating speed, triggering wave after wave of confusing panic. It's not exactly the case that Eastwood is stretching himself, but this is the most awake, propulsive film he's made this decade, and it's nice to see a solid workhorse demonstrating just how enjoyable solid work can actually be.

I bring these flaws not to complain, but to celebrate their absence: Richard Jewell, his 38th feature as director (one always itches to add "and perhaps his last" to everything the 89-year-old touches, but I will live in hope), is perhaps his first film of the 2010s that suffers from neither of those two flaws. There's one performance that needed more time in the oven, and a final scene that would have been better-served by a bland expository title card (and I say this as someone for whom expository title cards are not a small reason that I detest biopics), among other small writing fuck-ups, but overall this is material that plays atypically well to Eastwood's strengths, enough for me to call it with only a little hesitation his best film since Letters from Iwo Jima in 2006 (which I expect will remain the terminal point in all "Clint's best film since ____" conversations no matter how much longer he works). This is especially a nice treat coming after such a wildly uneven decade, especially given that we're not two full years removed from the wholly unforgivable The 15:17 to Paris, the kind of film that not even a lifelong Clint Eastwood apologist could possibly find a way to apologise for.

Richard Jewell is, you'll be shocked to hear, the story of Richard Jewell (Paul Walter Hauser), a wannabe cop who can't find anything closer than being an overbearing security guard in his home town of Atlanta. In this capacity, in 1996, he ended up working at Centennial Park during the Summer Olympics, where his paranoia paid off when he spotted a suspicious backpack that turned out to be a homemade pipe bomb. For a few days, he was celebrated in the national spotlight as a hero, before word got out that the FBI was investigating him for the crime, at which point he became a national villain and punchline. This movie, adapted by Billy Ray from an article and book about the events of that summer, functions mostly as an attempt to apologise to him for the extravagant speed with which he went from being praised to screamed at. For this would most likely have fucked with the head of anybody; given that Jewell was (if the film is right) already a bit of a broken, unstable person, it fucked with his head a lot.

That's the first strength of many: this isn't anything like a hagiography. Ray, Eastwood, and Hauser are very open in presenting Richard as an unlikable and pathetic figure. The first we see him, he's an office functionary at the Small Business Administration with creepy boundary issues, trying to impress lawyer Watson Bryant (Sam Rockwell, calming down and just giving a human-scale performance for the first time in what feels like years) by getting way too far into the other man's space. Even though Watson eventually decides to find this amusing rather than unsettling, first impressions in movies like life are lasting impressions, and Richard seems no less of an off-putting sad sack as we get to know him better: his groveling, insipid way of talking to anyone in law enforcement, in particular, is so irritating that the other sympathetic characters in the film all take him to task for it. He's awfully cringe-inducing for a hero, with his one great moment coming not because he's observant, but because he's dysfunctionally neurotic, and can't let go of the idea that every backpack hides a bomb; this one time, he just so happens to be right.

Having a prickly, uncomfortable protagonist like this probably isn't in and of itself enough to make Richard Jewell a good movie, but given the great psychological flattening that has afflicted so much of Oscarbait cinema in the 2010s, I'll take it. Especially given Hauser's performance, one of the year's best: his Richard is a quiet, shuffling bear of a man, awkward in his own body (Hauser nails the way that an insecure overweight man tries to direct attention away from himself by looking down and talking softly), keenly observant in ways that are a bit nerve-wracking to watch, given that he also seems (seems) to be very bad at understanding the things that he's observing, and so we're always waiting for this or that shoe to drop. The slight gradations in how he plays the character when he's comfortable with his scene partners - as he is with Kathy Bates, playing his mother, and doing a very fine job with a very functional role - versus when he's trying to wheedle and impress them is slightly heartbreaking, and its payoff near the end of the film is one of the most satisfying character beats in an Eastwood film in a very long time. The whole thing is more interested in characters than their actions, really, which is unusual for this filmmaker, but the fascination in watching people thinking and being is pervasive: there's a scene of people just hanging out and enjoying Kenny Rogers that is, in a very soft way, one of the most humane things in any Eastwood film, and even the designated villains - FBI Agent Tom Shaw (Jon Hamm) and journalist Kathy Scruggs (Olivia Wilde, the film's sole example of an actor who needed something Eastwood wasn't providing; she's chomping into the dialogue with a lot more melodramatic zeal than anything else in the film) - are still looked at with an interest that's less about their function in the plot than simply trying to figure out how they work and think.

This is overtly a Republican-facing message movie, but the most satisfying parts of the film have nothing to do with the message, and are far more elemental. This is basically a Kafkaesque fable about a man who has spent his whole life trying to be affable and abiding by the rules being plunged into a system where the nicer he tries to be, the worse he makes it for himself. The cinematography, by Yves Bélanger, is too soft and fuzzy, and the cutting, by Eastwood regular Joel Cox, is too devoid of urgency to honestly suggest that this has the tension necessary to qualify as a thriller, but that's where a lot of the plot and much of the acting suggests we are: a dive into an inexplicable terror at ever-escalating speed, triggering wave after wave of confusing panic. It's not exactly the case that Eastwood is stretching himself, but this is the most awake, propulsive film he's made this decade, and it's nice to see a solid workhorse demonstrating just how enjoyable solid work can actually be.

Categories: clint eastwood, crime pictures, oscarbait, the dread biopic