The life of a repo man is always intense

A review requested by Michael, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

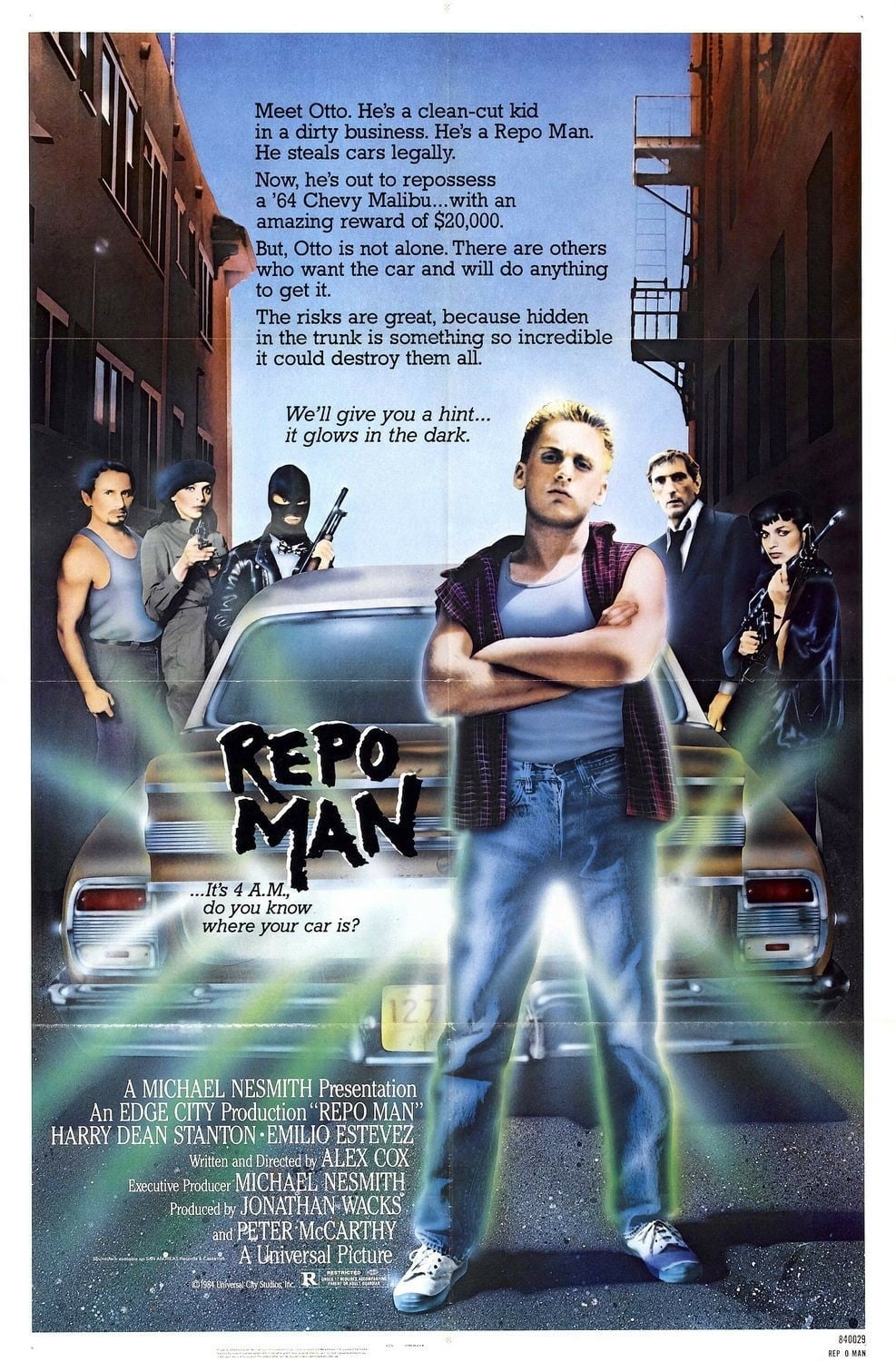

I came in at least a decade too late to be in any way involved with the 1980s punk scene, and I really can't imagine that I'd have been a part of it even if I was of an age, but nothing I've ever encountered has made me feel so viscerally amped up by whatever it is the punks were up to as 1984's Repo Man, writer-director Alex Cox's scorched-earth satire of the Reagan '80s. It is a caustic, cynical, nihilistic comedy in which the very notion of taking things seriously or caring about anything is treated with the utmost scorn, all while painting a damning portrait of culture as it stood at that exact moment in time, so persuasively repulsed by every aspect of American life in that decade that a good dose of "fuck you" nihilism seems to be just about the only legitimate response.

For almost half of its pummeling, high-speed 92 minutes, Repo Man looks very much like just a particularly sympathetic and cartoonish version of the punksploitation cycle that was thriving in the first half of the 1980s (including alarmist films like Class of 1984, understanding films like Suburbia, and ludicrous films like Rock 'n' Roll High School). Otto (Emilio Estevez, giving the best performance of his career) is just another L.A. punk, fallen on hard times: he sassed his boss and lost his shitty job at a crummy grocery store, and his girlfriend Debbi (Jennifer Balgobin) has been sleeping around with his best friend Duke (Dick Rude). So Otto, it is fair to say, has nothing going for him, until the day that a peculiar middle-aged man named Bud (Harry Dean Stanton) offers him $25 to drive Bud's second car while he takes the first to the hospital where his wife is having a baby. This is transparently weird, but Otto needs the cash, so he follows Bud to the offices of Helping Hand Acceptance Corporation, where he learns the truth: Bud is a repossession agent, a damnable repo man, and broke as he is, Otto isn't too good of a punk to throw his lot in with people who so directly represent The Man's willingness to destroy the lives of decent human beings over the slightest financial incentive.

Except that he's about to discover that he's even more broke than he thought: his parents have become zombies in thrall to a singularly unconvincing televangelist, Reverend Larry (Bruce White), and given away every penny of their savings. So back Otto goes to Helping Hand, where he learns the business from the various whackadoodle figures who work there: Bud with his messianic "Repo Code", in direct opposition to the anarchic approach taken Lite (Sy Richardson), the firm's other leading repo man; Oly (Tom Finnegan), the rage-prone manager of the joint; Miller (Tracey Walter), the mechanic, who has the visionary madness of a holy fool; Plettschner (Richard Foronjy), a mildly psychotic security guard; and Marlene (Vonetta McGee), who runs the office and appears to be its sole tether to actual humanity. For a good long while after this, Otto is just learning the ropes, listening to his coworkers expound at great, great length on their philosophies and paranoias, and learning that it is quite fun to be able to drive around in nice cars to pick up women, as he does with Leila (Olivia Barash) one day. And the fact that Leila turns out to be a raving UFO conspiracy theorist doesn't spoil the principle of the thing.

All in all, a pretty straightforward, effectively snarling full-frontal assault on society. Otto's omnipresent cynicism is justified, within the film, by the utter disdain with which Repo Man depicts Los Angeles as a hell of mindless consumerism, starting with those repossessed cars; as Bud acerbically notes, the repo men's targets are just as likely to be millionaires who've decided for whatever reason that their privilege in the world means they can buy shit without having to bother paying for it. But the more (deservedly) iconic indictment of mindless consumer culture is the film's use of generic items in every grocery store, convenience store, and kitchen in the film. This was a jab at the short-lived generic fad in the United States, where store shelves were lined with bland packages of duochromatic rectangles - in Repo Man, they're white packages with a single light blue stripe and dark blue lettering flatly declaring that we're looking at CORN FLAKES or FOOD - MEAT FLAVORED or DRY GIN. It's an ingenious production design gag that is never once referenced by a single character, which is part of why it never stops being funny, and it's doing a great deal of satiric work: it reduces product consumption to the level of pure animal instinct, where things exist as pure commodities, stripped of identity or personality of any sort. It's just flat, lifeless stuff. And by placing this increasingly recognisable label in so many places throughout the film, the filmmakers are calling our attention directly to how much that stuff has wormed its way into our daily lives.

It's the foundation for a hell of a great teardown of an atomised society full of alienated people, turned up to caricatured levels by Cox and his fantastically committed cast. Everything about Repo Man's early passages are turned in that direction: the running gag about how every time Otto enters a convenience store, there's a hold-up either just completed or about to happen, the running gag about how everybody but Otto has an extremely convoluted, kludged-together worldview designed to make them seem like a hero and everyone else is a shallow rube. It's shot perfectly by the great Robby Müller, still at the start of his career: his very next film was Paris, Texas, also starring Stanton, and it's astonishing how many of that film's visual conceits for isolating a protagonist in a wide shot (a lot of low camera heights and slightly distorted wide-angle lenses, plus purposefully reducing the fill on characters lit from above by strong direct sunlight) were given a trial run here. The films would make a phenomenal double feature, for that matter: Wim Wenders makes his story about the decay of American culture the way an artfully mournful outsider might, slowing things down to an imperceptible crawl and looking with solemn dismay at the vacant emptiness of desert, while Cox is cramming an urban landscape full of bric-à-brac, screaming as loud as he can through the lovingly-curated punk soundtrack, and treating everything with snotty, sarcastic humor; but they're looking at exactly the same thing. Americans were promised something through myths about individualism and resourcefulness, and those promises were lies, and now everything is simply horrible and beastly. Do it as slow art cinema, do it as punksploitation, the message comes through loudly either way.

Repo Man at least has a great sense of humor to keep the miserabilism at bay. It doesn't pretend that punk will save us (indeed, the opposite: near the end, a punk rock group is playing a stiff, low-tempo song with banal, conformist lyrics; it is one of the best jokes about how artists will always eventually sell out that I think I've ever seen), but it does admire the punks for being angry rather than complacent, and it finds a way to transform their anger into a kind of "you gotta laugh to keep from crying" vibe. The generic products are a big part of that, as are the moments that the film parodies the outrage of Nice People at subcultures daring to exist (the most nasty-minded punk in the movie is Duke, presented throughout as mildly dorky and neurotic; "Let's go do those crimes" says Debbi at one point, to which he responds with a gleeful snarl, "Let's go get sushi and not pay"). It's a mocking film, but it understands, as its punk characters themselves perhaps do not, that the point of mockery is to generate laughter, not a smug feeling of superiority.

All of this is, somehow, only one half of the film. Before we've ever met Otto, in fact, we've met J. Frank Parnell (Fox Harris), though it's a long time before we'll learn his name: he's a man with an eyepatch speeding westward in a '64 Chevy Malibu from Los Alamos, New Mexico - that's the Los Alamos where the atomic bomb was developed - with his trip rendered during the opening credits in sickening, toxic green-on-black road maps that are cut frantically to the roaring rock music on the soundtrack. And he's got something in his trunk that does two things: 1) glows, and 2) instantly vaporises any human who looks at it into ash. Once we learn this in the film's opening scene, it's put away for a long time. Long enough, in fact, that it's easy to forget about it: this film is putting a lot of stimulus in front of us, and as hard as it might be to imagine that "glowing light that skeletonises a highway cop" can be shuffled to the back of your brain, Repo Man manages to do it. Things come to a head when that '64 Malibu ends up in Los Angeles, and through a series of thefts and deaths-by-radioactive-glow, ends up in the Helping Hand. And it would be spoiling things something terrible to talk about it in more detail than that, but this is where Repo Man evolves from being merely an excellent film about social anomie, loneliness, and desperate need to cling to any subculture that will take you as a way of staving off those things, and becomes that plus a '50s-style paranoia thriller about how there actually is meaning and logic to the world, it's just actively malicious. And, in the most astonishing twist of all, it ends on a moment of weird, cock-eyed hope, in which the film's biggest cynic and its most whacked-out true believer are brought together and rewarded, maybe.

So in short,, we have here urban rot presented through a layer of comic stylistic excess, and we have sprawling sci-fi fantasy presented with the flat directness of urban realism. These combine seamlessly to make one of the most dazzling, original films of the 1980s, and one of that decade's most supremely successful directorial debuts. It's a lamentable shame that Cox's career would fizzle out so quickly, especially given that his first two films (the next was the punk biopic Sid & Nancy) were so damn great - and not even the kind of greatness only retroactively recognised; they were both critical hits when they were new (though Sid & Nancy lost money). A pity, then, that such a distinct satirical voice and inventive visual storyteller would be given so few chances to shine, but at least we have Repo Man in all its filthy glory, one of the most perfect cinematic embodiments of the 1980s but also a feisty leftist broadside against the middlebrow that doesn't feel like it's aged a day.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

I came in at least a decade too late to be in any way involved with the 1980s punk scene, and I really can't imagine that I'd have been a part of it even if I was of an age, but nothing I've ever encountered has made me feel so viscerally amped up by whatever it is the punks were up to as 1984's Repo Man, writer-director Alex Cox's scorched-earth satire of the Reagan '80s. It is a caustic, cynical, nihilistic comedy in which the very notion of taking things seriously or caring about anything is treated with the utmost scorn, all while painting a damning portrait of culture as it stood at that exact moment in time, so persuasively repulsed by every aspect of American life in that decade that a good dose of "fuck you" nihilism seems to be just about the only legitimate response.

For almost half of its pummeling, high-speed 92 minutes, Repo Man looks very much like just a particularly sympathetic and cartoonish version of the punksploitation cycle that was thriving in the first half of the 1980s (including alarmist films like Class of 1984, understanding films like Suburbia, and ludicrous films like Rock 'n' Roll High School). Otto (Emilio Estevez, giving the best performance of his career) is just another L.A. punk, fallen on hard times: he sassed his boss and lost his shitty job at a crummy grocery store, and his girlfriend Debbi (Jennifer Balgobin) has been sleeping around with his best friend Duke (Dick Rude). So Otto, it is fair to say, has nothing going for him, until the day that a peculiar middle-aged man named Bud (Harry Dean Stanton) offers him $25 to drive Bud's second car while he takes the first to the hospital where his wife is having a baby. This is transparently weird, but Otto needs the cash, so he follows Bud to the offices of Helping Hand Acceptance Corporation, where he learns the truth: Bud is a repossession agent, a damnable repo man, and broke as he is, Otto isn't too good of a punk to throw his lot in with people who so directly represent The Man's willingness to destroy the lives of decent human beings over the slightest financial incentive.

Except that he's about to discover that he's even more broke than he thought: his parents have become zombies in thrall to a singularly unconvincing televangelist, Reverend Larry (Bruce White), and given away every penny of their savings. So back Otto goes to Helping Hand, where he learns the business from the various whackadoodle figures who work there: Bud with his messianic "Repo Code", in direct opposition to the anarchic approach taken Lite (Sy Richardson), the firm's other leading repo man; Oly (Tom Finnegan), the rage-prone manager of the joint; Miller (Tracey Walter), the mechanic, who has the visionary madness of a holy fool; Plettschner (Richard Foronjy), a mildly psychotic security guard; and Marlene (Vonetta McGee), who runs the office and appears to be its sole tether to actual humanity. For a good long while after this, Otto is just learning the ropes, listening to his coworkers expound at great, great length on their philosophies and paranoias, and learning that it is quite fun to be able to drive around in nice cars to pick up women, as he does with Leila (Olivia Barash) one day. And the fact that Leila turns out to be a raving UFO conspiracy theorist doesn't spoil the principle of the thing.

All in all, a pretty straightforward, effectively snarling full-frontal assault on society. Otto's omnipresent cynicism is justified, within the film, by the utter disdain with which Repo Man depicts Los Angeles as a hell of mindless consumerism, starting with those repossessed cars; as Bud acerbically notes, the repo men's targets are just as likely to be millionaires who've decided for whatever reason that their privilege in the world means they can buy shit without having to bother paying for it. But the more (deservedly) iconic indictment of mindless consumer culture is the film's use of generic items in every grocery store, convenience store, and kitchen in the film. This was a jab at the short-lived generic fad in the United States, where store shelves were lined with bland packages of duochromatic rectangles - in Repo Man, they're white packages with a single light blue stripe and dark blue lettering flatly declaring that we're looking at CORN FLAKES or FOOD - MEAT FLAVORED or DRY GIN. It's an ingenious production design gag that is never once referenced by a single character, which is part of why it never stops being funny, and it's doing a great deal of satiric work: it reduces product consumption to the level of pure animal instinct, where things exist as pure commodities, stripped of identity or personality of any sort. It's just flat, lifeless stuff. And by placing this increasingly recognisable label in so many places throughout the film, the filmmakers are calling our attention directly to how much that stuff has wormed its way into our daily lives.

It's the foundation for a hell of a great teardown of an atomised society full of alienated people, turned up to caricatured levels by Cox and his fantastically committed cast. Everything about Repo Man's early passages are turned in that direction: the running gag about how every time Otto enters a convenience store, there's a hold-up either just completed or about to happen, the running gag about how everybody but Otto has an extremely convoluted, kludged-together worldview designed to make them seem like a hero and everyone else is a shallow rube. It's shot perfectly by the great Robby Müller, still at the start of his career: his very next film was Paris, Texas, also starring Stanton, and it's astonishing how many of that film's visual conceits for isolating a protagonist in a wide shot (a lot of low camera heights and slightly distorted wide-angle lenses, plus purposefully reducing the fill on characters lit from above by strong direct sunlight) were given a trial run here. The films would make a phenomenal double feature, for that matter: Wim Wenders makes his story about the decay of American culture the way an artfully mournful outsider might, slowing things down to an imperceptible crawl and looking with solemn dismay at the vacant emptiness of desert, while Cox is cramming an urban landscape full of bric-à-brac, screaming as loud as he can through the lovingly-curated punk soundtrack, and treating everything with snotty, sarcastic humor; but they're looking at exactly the same thing. Americans were promised something through myths about individualism and resourcefulness, and those promises were lies, and now everything is simply horrible and beastly. Do it as slow art cinema, do it as punksploitation, the message comes through loudly either way.

Repo Man at least has a great sense of humor to keep the miserabilism at bay. It doesn't pretend that punk will save us (indeed, the opposite: near the end, a punk rock group is playing a stiff, low-tempo song with banal, conformist lyrics; it is one of the best jokes about how artists will always eventually sell out that I think I've ever seen), but it does admire the punks for being angry rather than complacent, and it finds a way to transform their anger into a kind of "you gotta laugh to keep from crying" vibe. The generic products are a big part of that, as are the moments that the film parodies the outrage of Nice People at subcultures daring to exist (the most nasty-minded punk in the movie is Duke, presented throughout as mildly dorky and neurotic; "Let's go do those crimes" says Debbi at one point, to which he responds with a gleeful snarl, "Let's go get sushi and not pay"). It's a mocking film, but it understands, as its punk characters themselves perhaps do not, that the point of mockery is to generate laughter, not a smug feeling of superiority.

All of this is, somehow, only one half of the film. Before we've ever met Otto, in fact, we've met J. Frank Parnell (Fox Harris), though it's a long time before we'll learn his name: he's a man with an eyepatch speeding westward in a '64 Chevy Malibu from Los Alamos, New Mexico - that's the Los Alamos where the atomic bomb was developed - with his trip rendered during the opening credits in sickening, toxic green-on-black road maps that are cut frantically to the roaring rock music on the soundtrack. And he's got something in his trunk that does two things: 1) glows, and 2) instantly vaporises any human who looks at it into ash. Once we learn this in the film's opening scene, it's put away for a long time. Long enough, in fact, that it's easy to forget about it: this film is putting a lot of stimulus in front of us, and as hard as it might be to imagine that "glowing light that skeletonises a highway cop" can be shuffled to the back of your brain, Repo Man manages to do it. Things come to a head when that '64 Malibu ends up in Los Angeles, and through a series of thefts and deaths-by-radioactive-glow, ends up in the Helping Hand. And it would be spoiling things something terrible to talk about it in more detail than that, but this is where Repo Man evolves from being merely an excellent film about social anomie, loneliness, and desperate need to cling to any subculture that will take you as a way of staving off those things, and becomes that plus a '50s-style paranoia thriller about how there actually is meaning and logic to the world, it's just actively malicious. And, in the most astonishing twist of all, it ends on a moment of weird, cock-eyed hope, in which the film's biggest cynic and its most whacked-out true believer are brought together and rewarded, maybe.

So in short,, we have here urban rot presented through a layer of comic stylistic excess, and we have sprawling sci-fi fantasy presented with the flat directness of urban realism. These combine seamlessly to make one of the most dazzling, original films of the 1980s, and one of that decade's most supremely successful directorial debuts. It's a lamentable shame that Cox's career would fizzle out so quickly, especially given that his first two films (the next was the punk biopic Sid & Nancy) were so damn great - and not even the kind of greatness only retroactively recognised; they were both critical hits when they were new (though Sid & Nancy lost money). A pity, then, that such a distinct satirical voice and inventive visual storyteller would be given so few chances to shine, but at least we have Repo Man in all its filthy glory, one of the most perfect cinematic embodiments of the 1980s but also a feisty leftist broadside against the middlebrow that doesn't feel like it's aged a day.

Categories: comedies, gorgeous cinematography, satire, science fiction