After midnight

A review requested by Andrew, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Amblin Entertainment is still with us, as we enter the third decade of the 21st Century (dear God, and how Amblin is still with us), but it's not really Amblin Entertainment anymore, not the way it used to be. Those of you who are a touch on the younger side might not realise just how big Amblin was in the '80s and early '90s, when the company's name immediately called up the image of Steven Spielberg, and when Spielberg himself was still the brand name filmmaker, a cast-iron guarantor of some level of quality, family-friendliness, and astonishing movie magic and technical whiz-bang. I'm not exactly sure when that started to fade away (slapping the Amblin name on the gravely miserable Schindler's List surely had to be part of it), but for a while, Amblin was as much a sensibility about what "the movies" even looked like, as a simple production company.

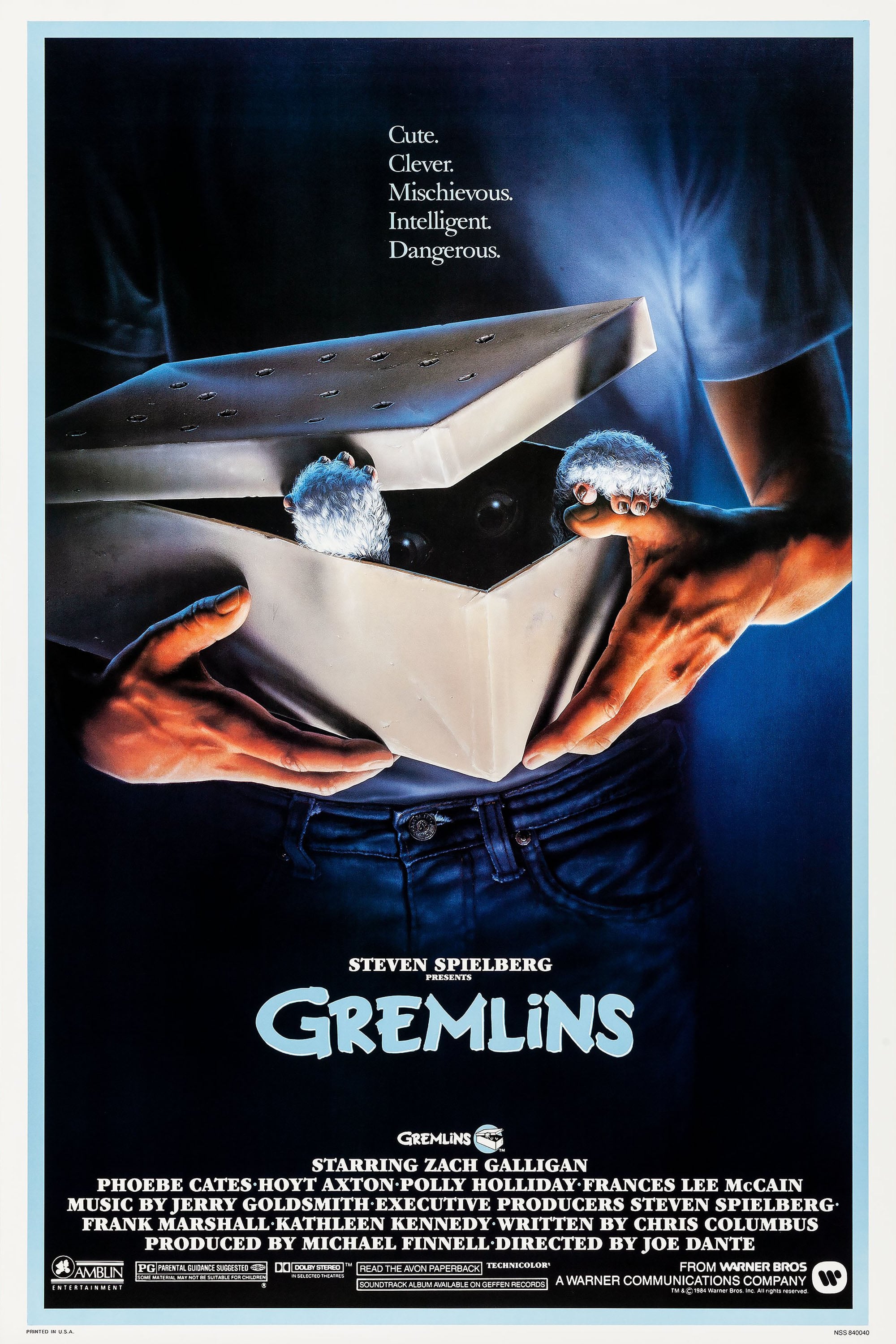

I bring this up now, of all times, because Gremlins, directed by Joe Dante and written by Chris Columbus, is an Amblin film; it is one of my favorite Amblin films; and it might honest to God be the single most perverse subversion of the Amblin shingle ever released. And I include the 3.25-hour black-and-white Holocaust drama in that consideration. To start, Gremlins is only slightly hiding how much it's playing on the recent box office supernova E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Spielberg's most nakedly sentimental film and probably the most Ambliney Amblin film of them all (it is the source of the Amblin logo). They are both stories about life in a cozy little suburb when the suburbs still could pretend to be old-timey small towns; they are both about lonely, awkward young men being nudged to find out how to be their best selves thanks to the introduction of an adorable little creature played by state-of-the-art puppetry and robotics. Only one of them ends with the villain of the piece having his skin melted off so that we can see the oozing muscles pulsing beneath as he screams in his death throes.

For that reason and others, Gremlins was one of the two Spielberg-adjacent films released in the summer of 1984 - it came out on 7 June, two weeks after Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom - that upset everybody so bad that it led directly to the creation of the PG-13 rating. And this feels exactly right. Taking the trappings of family-friendly fantasy and comedy and making it as nasty and black-hearted as possible is kind of exactly Gremlin's reason to exist. It is the darkest mainstream dark comedy of the '80s, a movie in which a scene of a woman recalling the trauma of finding her father's decaying corpse is played an absurd joke with a perfectly dry punchline. It's set entirely at Christmastime largely for the great pleasure it takes in corrupting Christmas iconography, much as it takes place in the shiny, tidy domestic realm of a nice suburban house mostly so that this setting can be the site of messy gore effects. The whole point of the movie is to take the charm promised by the Amblin and Spielberg names and then do something utterly vulgar with them, and if the concerned mothers of Reagan-era America were completely freaked out by that, so much the better.

In principle, I suppose this means that Gremlins is not for all tastes, but in practice I'm not sure that I've ever run into anybody who wasn't at least a little delighted by it. The film exists largely because Dante, fresh off of getting his big break from directing a segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie for Spielberg, wanted to do a live-action version of a Warner Bros. cartoon. That was, in fact, the focus of his Twilight Zone segment, "It's a Good Life", which remade one of the most beloved and famous episodes of the original series as a cartoon-colored spectacle of physical gags. For Gremlins, Dante and Columbus turned to a very specific Warner short, 1943's Falling Hare, in which Bugs Bunny crossed paths with a gremlin, the prankish creature joked about by airplane engineers during World War II to explain otherwise random mechanical failures. Falling Hare developed that urban legend by positing a gremlin who enjoyed fucking with Bugs just for the sake of being an asshole, and Gremlins takes it even further by suggesting active homicidal malevolence: the gremlins mostly do cause technology to fail, but ideally in a place that will maximise damage to the humans using that technology. And in a pinch, they're also happy to just run you over with a snow plow.

The point being that Gremlins is basically just slapstick comedy on the Looney Tunes model. Really fucking violent slapstick comedy, for in addition to being a fan of cartoons, Dante was also trained in gory exploitation cinema: before Spielberg plucked him out of the trenches, he'd already helmed 1978's Piranha (for Roger Corman, no less!) and 1981's The Howling. The former, in particular, is something of a dry run for Gremlins's mix of bloodiness and comedy, though Piranha is nowhere near as overt in its preference for laughs over scares. Still, you don't need to be a horror expert to see that a live-action Looney Tune would of its nature involve a lot of grievous bodily harm, and thus could only be presented as horror (as in Twilight Zone) or outright absurdity, like we get here. What exactly Dante and Columbus had to do in order to keep Gremlins reliably fun and funny rather than ever once tipping over into actual horror is hard to say: a big part of it is by having every human character other than the protagonists written and performed as big, squirrelly caricatures. And those protagonists, mild-mannered Billy Peltzer (Zach Galligan) and banal nice girl Kate Beringer (Phoebe Cates), are pretty flat and generic types, almost purposefully devoid of any personality other than the hints that they're both a bit poorer than most of their peers.

Which is also part of what allows Gremlins to be funny rather than morbid: it picks the right targets. The film isn't as openly satiric as Piranha or 1990's Gremlins 2: The New Batch, a movie that's so much more ambitious and manic than Gremlins that I often misremember the original film as being a bit sedate and safe. And certainly, it's not as befanged in its assault on the hollowness of upper-middle-class white suburbanites as The New Batch is in its scorched-earth takedown of pop media, consumerism, and a certain venal New York businessman named Donald Trump. But it has little tiny fangs nonetheless. The film has a pretty standard three-part horror structure: first we see a stable system, then the monsters arrive in that system and disrupt it, then the heroes figure out how to fight back. The first of those parts is devoted almost entirely to defining the small town as Kingston Falls as a place where everybody cares about things: be they useless gadgets, like Billy's dad, or cars, like Billy's neighbors, or fancy Christmas decorations, like his archnemesis Mrs. Deagle (Polly Holliday), or just pure money, like his other archnemesis, Gerald (Judge Reinhold). The joy of Gremlins comes in large part because of the relish with which the gremlins destroy all of these things; while we don't exactly root for them, and their messy deaths are played purely for laughs, we also can't help but get a kick out of seeing their perverse takedown of all the things we attach to the American Dream.

This even extends to the film's E.T. analogue, an adorable floppy-eared critter called a mogwai (the Cantonese word for "devil"), named Gizmo. He's a marvelous big of engineering, with an elaborately expressive face (including special extra-large faces designed just for close-ups), and given an endearing child's voice by comedian Howie Mandel; he's sweet, cute, extremely toyetic (Gizmo dolls were one of the best-selling toys of Christmas '84, in an especially pungent irony), and the filmmakers take great pleasure in abusing him. Indeed, there was even a list the special effects artists kept, of all of the cruel gags they thought it might be fun to mete out on the puppet (The New Batch ran much farther with this, to its credit).

The whole thing should be nasty, but it's just not. There's too much obvious joy in the craft, for one. Dante was an inveterate fan of classical Hollywood, and there's a giddy love of movies and moviemaking throughout Gremlins, from its film noir parody opening narration to its clips from classical movies to the loving care with which which the filmmakers showcased their mogwai and gremlin puppets. Not to mention the bottomless enthusiasm with it worships the mad logic of Warner Bros. cartoons It is ebullient, fannish filmmaking of the first order. And it's also just a very high-energy movie, clicking along at a nice pace and racing from gag to gag (in the scene where Billy's mom, played by Frances Lee McCain, first encounters the gremlins, it moves between jokes so fast that there's not even enough time for an edit). It also benefits from one of the most underappreciated musical scores of the 1980s: Jerry Goldsmith composed a bunch of relatively generic string-music - very knock-off John Williams stuff, appropriately - for the early scenes of people milling around in their tidy town. It's not doing anything, to an almost aggressive degree, and this turns out to be entirely so that he can break the soundtrack apart by introducing "The Gremlin Rag", one of the very best main themes of any '80s movie. It's the most appallingly '80s thing you can imagine, all ugly synths bouncing off of a manic beat - it's angular and splatting and electronic, an aural assault that's cartoonishly bouncy, and feels like horror music done as a gleeful celebration of the monster rather than a way of driving tension. In other words, the perfect sonic accompaniment for the gremlins themselves, and there might be no better explanation for why Gremlins is so damn fun than the fact that this song is right there, putting a devilish smile to the darkest, meanest jokes in the film. At any rate, something is working to make this, the '80s comedy with the highest body count I can name, so bright and entertaining and festive.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Amblin Entertainment is still with us, as we enter the third decade of the 21st Century (dear God, and how Amblin is still with us), but it's not really Amblin Entertainment anymore, not the way it used to be. Those of you who are a touch on the younger side might not realise just how big Amblin was in the '80s and early '90s, when the company's name immediately called up the image of Steven Spielberg, and when Spielberg himself was still the brand name filmmaker, a cast-iron guarantor of some level of quality, family-friendliness, and astonishing movie magic and technical whiz-bang. I'm not exactly sure when that started to fade away (slapping the Amblin name on the gravely miserable Schindler's List surely had to be part of it), but for a while, Amblin was as much a sensibility about what "the movies" even looked like, as a simple production company.

I bring this up now, of all times, because Gremlins, directed by Joe Dante and written by Chris Columbus, is an Amblin film; it is one of my favorite Amblin films; and it might honest to God be the single most perverse subversion of the Amblin shingle ever released. And I include the 3.25-hour black-and-white Holocaust drama in that consideration. To start, Gremlins is only slightly hiding how much it's playing on the recent box office supernova E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Spielberg's most nakedly sentimental film and probably the most Ambliney Amblin film of them all (it is the source of the Amblin logo). They are both stories about life in a cozy little suburb when the suburbs still could pretend to be old-timey small towns; they are both about lonely, awkward young men being nudged to find out how to be their best selves thanks to the introduction of an adorable little creature played by state-of-the-art puppetry and robotics. Only one of them ends with the villain of the piece having his skin melted off so that we can see the oozing muscles pulsing beneath as he screams in his death throes.

For that reason and others, Gremlins was one of the two Spielberg-adjacent films released in the summer of 1984 - it came out on 7 June, two weeks after Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom - that upset everybody so bad that it led directly to the creation of the PG-13 rating. And this feels exactly right. Taking the trappings of family-friendly fantasy and comedy and making it as nasty and black-hearted as possible is kind of exactly Gremlin's reason to exist. It is the darkest mainstream dark comedy of the '80s, a movie in which a scene of a woman recalling the trauma of finding her father's decaying corpse is played an absurd joke with a perfectly dry punchline. It's set entirely at Christmastime largely for the great pleasure it takes in corrupting Christmas iconography, much as it takes place in the shiny, tidy domestic realm of a nice suburban house mostly so that this setting can be the site of messy gore effects. The whole point of the movie is to take the charm promised by the Amblin and Spielberg names and then do something utterly vulgar with them, and if the concerned mothers of Reagan-era America were completely freaked out by that, so much the better.

In principle, I suppose this means that Gremlins is not for all tastes, but in practice I'm not sure that I've ever run into anybody who wasn't at least a little delighted by it. The film exists largely because Dante, fresh off of getting his big break from directing a segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie for Spielberg, wanted to do a live-action version of a Warner Bros. cartoon. That was, in fact, the focus of his Twilight Zone segment, "It's a Good Life", which remade one of the most beloved and famous episodes of the original series as a cartoon-colored spectacle of physical gags. For Gremlins, Dante and Columbus turned to a very specific Warner short, 1943's Falling Hare, in which Bugs Bunny crossed paths with a gremlin, the prankish creature joked about by airplane engineers during World War II to explain otherwise random mechanical failures. Falling Hare developed that urban legend by positing a gremlin who enjoyed fucking with Bugs just for the sake of being an asshole, and Gremlins takes it even further by suggesting active homicidal malevolence: the gremlins mostly do cause technology to fail, but ideally in a place that will maximise damage to the humans using that technology. And in a pinch, they're also happy to just run you over with a snow plow.

The point being that Gremlins is basically just slapstick comedy on the Looney Tunes model. Really fucking violent slapstick comedy, for in addition to being a fan of cartoons, Dante was also trained in gory exploitation cinema: before Spielberg plucked him out of the trenches, he'd already helmed 1978's Piranha (for Roger Corman, no less!) and 1981's The Howling. The former, in particular, is something of a dry run for Gremlins's mix of bloodiness and comedy, though Piranha is nowhere near as overt in its preference for laughs over scares. Still, you don't need to be a horror expert to see that a live-action Looney Tune would of its nature involve a lot of grievous bodily harm, and thus could only be presented as horror (as in Twilight Zone) or outright absurdity, like we get here. What exactly Dante and Columbus had to do in order to keep Gremlins reliably fun and funny rather than ever once tipping over into actual horror is hard to say: a big part of it is by having every human character other than the protagonists written and performed as big, squirrelly caricatures. And those protagonists, mild-mannered Billy Peltzer (Zach Galligan) and banal nice girl Kate Beringer (Phoebe Cates), are pretty flat and generic types, almost purposefully devoid of any personality other than the hints that they're both a bit poorer than most of their peers.

Which is also part of what allows Gremlins to be funny rather than morbid: it picks the right targets. The film isn't as openly satiric as Piranha or 1990's Gremlins 2: The New Batch, a movie that's so much more ambitious and manic than Gremlins that I often misremember the original film as being a bit sedate and safe. And certainly, it's not as befanged in its assault on the hollowness of upper-middle-class white suburbanites as The New Batch is in its scorched-earth takedown of pop media, consumerism, and a certain venal New York businessman named Donald Trump. But it has little tiny fangs nonetheless. The film has a pretty standard three-part horror structure: first we see a stable system, then the monsters arrive in that system and disrupt it, then the heroes figure out how to fight back. The first of those parts is devoted almost entirely to defining the small town as Kingston Falls as a place where everybody cares about things: be they useless gadgets, like Billy's dad, or cars, like Billy's neighbors, or fancy Christmas decorations, like his archnemesis Mrs. Deagle (Polly Holliday), or just pure money, like his other archnemesis, Gerald (Judge Reinhold). The joy of Gremlins comes in large part because of the relish with which the gremlins destroy all of these things; while we don't exactly root for them, and their messy deaths are played purely for laughs, we also can't help but get a kick out of seeing their perverse takedown of all the things we attach to the American Dream.

This even extends to the film's E.T. analogue, an adorable floppy-eared critter called a mogwai (the Cantonese word for "devil"), named Gizmo. He's a marvelous big of engineering, with an elaborately expressive face (including special extra-large faces designed just for close-ups), and given an endearing child's voice by comedian Howie Mandel; he's sweet, cute, extremely toyetic (Gizmo dolls were one of the best-selling toys of Christmas '84, in an especially pungent irony), and the filmmakers take great pleasure in abusing him. Indeed, there was even a list the special effects artists kept, of all of the cruel gags they thought it might be fun to mete out on the puppet (The New Batch ran much farther with this, to its credit).

The whole thing should be nasty, but it's just not. There's too much obvious joy in the craft, for one. Dante was an inveterate fan of classical Hollywood, and there's a giddy love of movies and moviemaking throughout Gremlins, from its film noir parody opening narration to its clips from classical movies to the loving care with which which the filmmakers showcased their mogwai and gremlin puppets. Not to mention the bottomless enthusiasm with it worships the mad logic of Warner Bros. cartoons It is ebullient, fannish filmmaking of the first order. And it's also just a very high-energy movie, clicking along at a nice pace and racing from gag to gag (in the scene where Billy's mom, played by Frances Lee McCain, first encounters the gremlins, it moves between jokes so fast that there's not even enough time for an edit). It also benefits from one of the most underappreciated musical scores of the 1980s: Jerry Goldsmith composed a bunch of relatively generic string-music - very knock-off John Williams stuff, appropriately - for the early scenes of people milling around in their tidy town. It's not doing anything, to an almost aggressive degree, and this turns out to be entirely so that he can break the soundtrack apart by introducing "The Gremlin Rag", one of the very best main themes of any '80s movie. It's the most appallingly '80s thing you can imagine, all ugly synths bouncing off of a manic beat - it's angular and splatting and electronic, an aural assault that's cartoonishly bouncy, and feels like horror music done as a gleeful celebration of the monster rather than a way of driving tension. In other words, the perfect sonic accompaniment for the gremlins themselves, and there might be no better explanation for why Gremlins is so damn fun than the fact that this song is right there, putting a devilish smile to the darkest, meanest jokes in the film. At any rate, something is working to make this, the '80s comedy with the highest body count I can name, so bright and entertaining and festive.

Categories: comedies, fantasy, here be monsters, horror, summer movies, tis the season, violence and gore