Big fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite 'em

Bong Joon-ho has been a brand-name director among cinephiles since 2006's monster movie-cum-domestic drama The Host, and South Korean cinema's ongoing golden age has been around for even longer, at least as far back as 2002's Oasis, directed by Lee Chang-dong. So there's not really any sense in which Bong's seventh feature, Parasite, is particularly new, particularly given the degree to which it functions as a collection of themes, techniques, and images that he has used before now. But it somehow feels fresh, fresh enough for it to have become the first Korean film to win the Palme d'Or. And while it's patently ludicrous that no film from that country has claimed that particular honor before the Year of Our Lord 2019, Parasite feels eminently worthy of bearing that weight. It is a great film, is the thing; a very great film, and the best Palme d'Or winner since The Tree of Life in 2011 (for me, the year that "Best Palme since _____" conversations are going to stall out for a very long time to come). Mind you, I don't even know that it's Bong's best film - the simple human emotions driving his 2009 Mother are hard to beat, and he's never married politics and genre mechanics better than in The Host despite multiple tries, including Parasite - but it is his most mature and perfect, the result of a filmmaker who has spent nearly two decades learning how to place and move the camera, how to manipulate audience expectations both to mislead us and to fulfill our wants, how to guide actors through arch, idiosyncratic character-building and scenarios too outlandish to feel so cozily naturalistic.

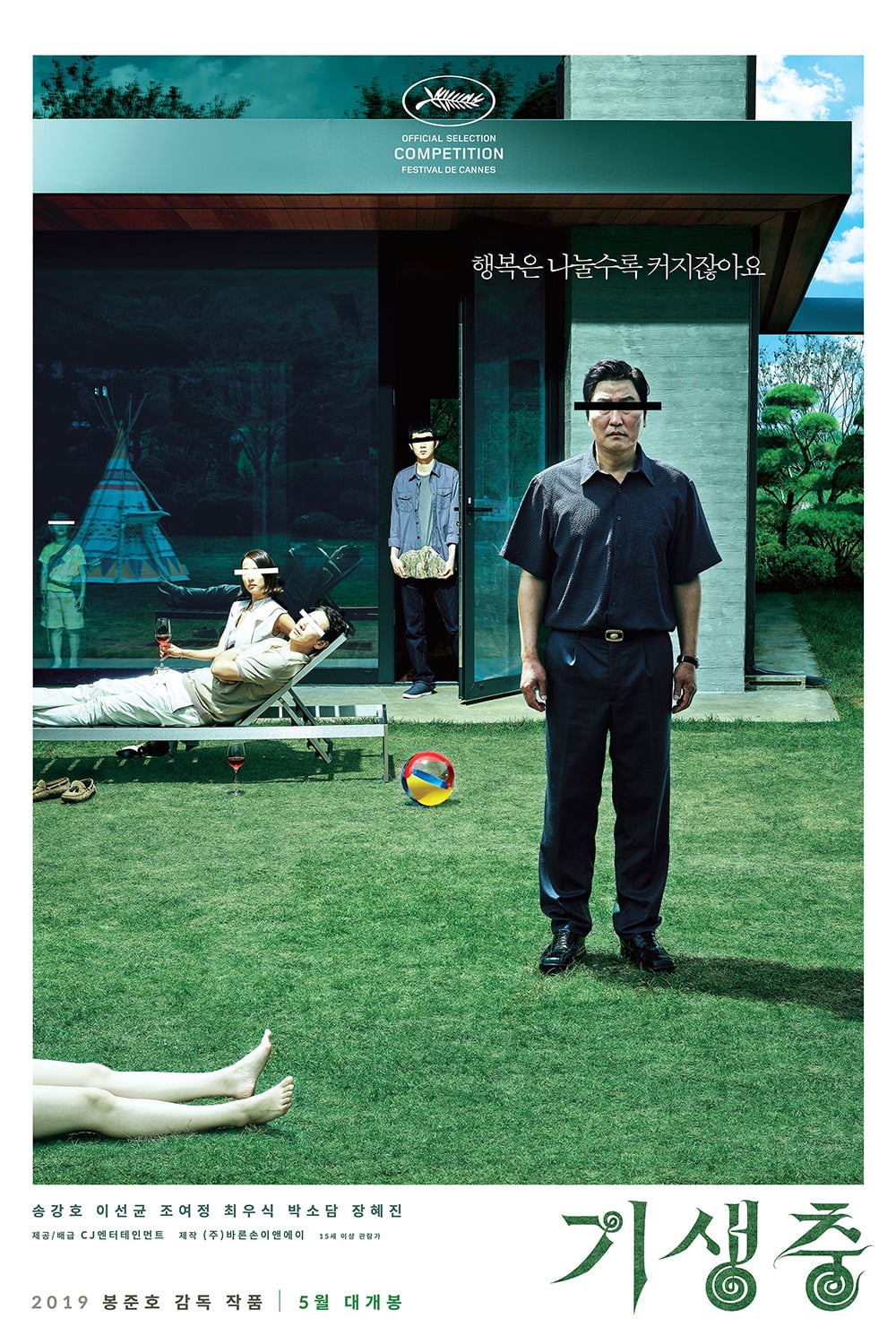

As I said, there's a little bit of every Bong film in Parasite, but the ones that are probably most important for plot and theme are The Host, a family drama about lower-class life being rudely interrupted by a thriller, and Snowpiercer, the most unapologetically anti-capitalist film in the career of a man who has spared no kind words for capitalism. The central characters are the members of the Kim family: father Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho, making his fourth film with Bong), mother Chung-sook (Jang Hye-jin), and college-aged children Ki-woo (Choi Woo-sik) and Ki-jung (Park So-dam). They live badly in a basement apartment, scraping together scraps of money from random jobs, and here they would live out the rest of their days, except that Ki-woo's better-off friend Min-hyuk (Park Seo-joon) is leaving the country to study. He leaves the Kims with two things: a lucky rock from his grandfather, blessed to bring wealth; and a position as English tutor for the teenage daughter of a rich family, the Parks. He's convinced that Ki-woo is the best man to replace him, and after a little white lie involving a non-existent college education, Ki-woo has charmed the socks off of dimwitted Mrs. Park (Jo Yeo-jeong) to take the job teaching Da-hye (Jung Ji-so). He then finds that the family is also looking for an art teacher to help little Da-song (Jung Hyun-jun), and soon Ki-jung is installed as well. She figures out a way to get Ki-taek hired as driver for Mr. Park (Lee Sun-kyun), and then all that's left is to force out the Parks' housemaid Moon-gwang (Lee Jeong-eun) to make room for Chung-sook to take that job.

So far, so delightful, as the film operates as a sort of offbeat caper comedy while the Kims work out their schemes to buffalo the Parks. It's merely the first movement of a movie that turns to have a whole lot of cards it wants to play, and some of them appear to have come from a different deck, and a different game. As is very common for Bong, Parasite ends up drawing from several different genres, though unlike the director's last film, the deliciously messy Okja, those genres are assembled in a largely smooth flow - no hopscotching about, just a clear shift from social realism into a comic caper/crime movie as the Kims insert themselves into the Parks' home, thence into a gruesomely tense thriller (kicked off by a brief flash of horror), which itself dissolves into an openly sad drama about the futility and inevitability of violence with a coda of magical realism. These shifts are handled front-and-center, especially when the caper comedy is wrenched into the thriller by means of a simply glorious tracking shot of almost unbearable tension and terror; they also, somehow, feel effortless and natural. I'm not equally in love with all of it: the coda, in particular, simply doesn't work, drawing the film's attention away too much from what it has been doing so successfully all along. But Bong and co-writer Won Han-jin have largely achieved something miraculous in building out a domestic epic that activates damn near every conceivable emotion in laying out their message from all angles.

That message is about economic exploitation, in a very tricky way. The Parks aren't the gross monsters of Snowpiercer, or the greedy vampires of Okja. They are nice, a word that gets used to describe them several times. And that, as they say, is where they get you. The satiric point Parasite is driving at isn't that the rich will devour the lives of the working class. It's that the working class is its own worst enemy, happily devouring itself to appeal to the smiling, kind people whose privilege gives them the opportunity to remain Nice, since they never have to face the desperation and privation that makes poor people Not So Nice. To say more would constitute a spoiler, but the film's refusal to make the Parks obvious, open villains (though the more we get to know them, the more we're invited to detect their subtle meanness) is probably why it works so well as satire; it doesn't rest on caricature and thus we can't so crisply separate it out from the real world.

Good satire or not, Parasite doesn't live and die on its message: it's also a hell of a fun film to watch, a bit overlong at 132 minutes, but generally so kinetic and vivacious that it never once feels boring. Which brings me back to the point I was aiming at in the first paragraph: Bong understands how to make cinema about as well as anybody now living. I have some reservations, small ones to be sure, with the way the story of Parasite develops; but as a piece of craftsmanship, I believe it is actually, literally flawless. Every time Bong and cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo set their camera down, it is exactly the right place for it. This is obviously true in the film's many show long takes and tracking shots, which tie the spaces of the film together in elaborate visual puzzles that invite us to think of the effect that living in particular locations has on the emotional lives of their inhabitants. And it's true, for the same reason, in the less showy moments that showcase Lee Ha-jun's exemplary production design: there are really just two locations, the respective families' houses, and they're both remarkable geometric objects. The Kims' basement hell is a series of cubes inside cubes, cramped and low; the Parks' gorgeous house, the work of an important architect we're told, is an airy, rectangular playground. Both of these locations are shown in similar, echoing shots (most tellingly, both have a window that copies the aspect ratio of the 2.35:1 film frame, placed into compositions maximising our awareness of this fact - to what end, I am admittedly unsure, but there's no missing it). And thus we get to compare them: the Kims' home is filthy and barely tolerable, but human, while the Parks' posh dwelling feels like you could not possibly actually live there, no matter how lavish and striking. It is inorganic, and the rigid compositions exaggerating the 90-degree angles throughout the set make it feel all the less so.

That's all the big stuff, though. Even in its most basic, fundamental building blocks, Parasite is up to some fascinating stuff: even the shot/reverse-shot sequences, the least-interesting thing it is possible to put into a movie, have an eccentric charge from the way that characters are placed into the frame, often too much too one side, and creating interesting imbalances as the image cuts between characters in dialogue. Not one shot has a sloppy or merely adequate composition. They are bursting with energy and life, bringing comedy to the funny bits and amplifying to uncertainty of the thriller sequences (there is a shot I'd hate to describe for fear of spoiling it, in which we have to make sense of two planes of action separated by a sheet of glass, and the further back plane also is divided into a left and right; it's already a tense moment, as we wait to see if a character is spotted being in the wrong place, and the amount of effort it takes to look at the image makes it more tense still). It's a film that does more than anything in quite some time to underscore the relationship between form and content - to erase any distinction between the two. The way that scenes are staged and the story being told are inseparable, our emotional reaction to the one being conditioned and focused by the other. It is the sort of thing that only a filmmaker in full command of all his powers could possibly make, and even if I don't think the whole experience is quite as fresh and exhilarating as e.g. Mother, I do think that Bong himself is at the very peak of his powers of crafting expressive visuals in Parasite. If he wasn't already one of our leading filmmakers, this would be more than enough to anoint him thus.

As I said, there's a little bit of every Bong film in Parasite, but the ones that are probably most important for plot and theme are The Host, a family drama about lower-class life being rudely interrupted by a thriller, and Snowpiercer, the most unapologetically anti-capitalist film in the career of a man who has spared no kind words for capitalism. The central characters are the members of the Kim family: father Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho, making his fourth film with Bong), mother Chung-sook (Jang Hye-jin), and college-aged children Ki-woo (Choi Woo-sik) and Ki-jung (Park So-dam). They live badly in a basement apartment, scraping together scraps of money from random jobs, and here they would live out the rest of their days, except that Ki-woo's better-off friend Min-hyuk (Park Seo-joon) is leaving the country to study. He leaves the Kims with two things: a lucky rock from his grandfather, blessed to bring wealth; and a position as English tutor for the teenage daughter of a rich family, the Parks. He's convinced that Ki-woo is the best man to replace him, and after a little white lie involving a non-existent college education, Ki-woo has charmed the socks off of dimwitted Mrs. Park (Jo Yeo-jeong) to take the job teaching Da-hye (Jung Ji-so). He then finds that the family is also looking for an art teacher to help little Da-song (Jung Hyun-jun), and soon Ki-jung is installed as well. She figures out a way to get Ki-taek hired as driver for Mr. Park (Lee Sun-kyun), and then all that's left is to force out the Parks' housemaid Moon-gwang (Lee Jeong-eun) to make room for Chung-sook to take that job.

So far, so delightful, as the film operates as a sort of offbeat caper comedy while the Kims work out their schemes to buffalo the Parks. It's merely the first movement of a movie that turns to have a whole lot of cards it wants to play, and some of them appear to have come from a different deck, and a different game. As is very common for Bong, Parasite ends up drawing from several different genres, though unlike the director's last film, the deliciously messy Okja, those genres are assembled in a largely smooth flow - no hopscotching about, just a clear shift from social realism into a comic caper/crime movie as the Kims insert themselves into the Parks' home, thence into a gruesomely tense thriller (kicked off by a brief flash of horror), which itself dissolves into an openly sad drama about the futility and inevitability of violence with a coda of magical realism. These shifts are handled front-and-center, especially when the caper comedy is wrenched into the thriller by means of a simply glorious tracking shot of almost unbearable tension and terror; they also, somehow, feel effortless and natural. I'm not equally in love with all of it: the coda, in particular, simply doesn't work, drawing the film's attention away too much from what it has been doing so successfully all along. But Bong and co-writer Won Han-jin have largely achieved something miraculous in building out a domestic epic that activates damn near every conceivable emotion in laying out their message from all angles.

That message is about economic exploitation, in a very tricky way. The Parks aren't the gross monsters of Snowpiercer, or the greedy vampires of Okja. They are nice, a word that gets used to describe them several times. And that, as they say, is where they get you. The satiric point Parasite is driving at isn't that the rich will devour the lives of the working class. It's that the working class is its own worst enemy, happily devouring itself to appeal to the smiling, kind people whose privilege gives them the opportunity to remain Nice, since they never have to face the desperation and privation that makes poor people Not So Nice. To say more would constitute a spoiler, but the film's refusal to make the Parks obvious, open villains (though the more we get to know them, the more we're invited to detect their subtle meanness) is probably why it works so well as satire; it doesn't rest on caricature and thus we can't so crisply separate it out from the real world.

Good satire or not, Parasite doesn't live and die on its message: it's also a hell of a fun film to watch, a bit overlong at 132 minutes, but generally so kinetic and vivacious that it never once feels boring. Which brings me back to the point I was aiming at in the first paragraph: Bong understands how to make cinema about as well as anybody now living. I have some reservations, small ones to be sure, with the way the story of Parasite develops; but as a piece of craftsmanship, I believe it is actually, literally flawless. Every time Bong and cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo set their camera down, it is exactly the right place for it. This is obviously true in the film's many show long takes and tracking shots, which tie the spaces of the film together in elaborate visual puzzles that invite us to think of the effect that living in particular locations has on the emotional lives of their inhabitants. And it's true, for the same reason, in the less showy moments that showcase Lee Ha-jun's exemplary production design: there are really just two locations, the respective families' houses, and they're both remarkable geometric objects. The Kims' basement hell is a series of cubes inside cubes, cramped and low; the Parks' gorgeous house, the work of an important architect we're told, is an airy, rectangular playground. Both of these locations are shown in similar, echoing shots (most tellingly, both have a window that copies the aspect ratio of the 2.35:1 film frame, placed into compositions maximising our awareness of this fact - to what end, I am admittedly unsure, but there's no missing it). And thus we get to compare them: the Kims' home is filthy and barely tolerable, but human, while the Parks' posh dwelling feels like you could not possibly actually live there, no matter how lavish and striking. It is inorganic, and the rigid compositions exaggerating the 90-degree angles throughout the set make it feel all the less so.

That's all the big stuff, though. Even in its most basic, fundamental building blocks, Parasite is up to some fascinating stuff: even the shot/reverse-shot sequences, the least-interesting thing it is possible to put into a movie, have an eccentric charge from the way that characters are placed into the frame, often too much too one side, and creating interesting imbalances as the image cuts between characters in dialogue. Not one shot has a sloppy or merely adequate composition. They are bursting with energy and life, bringing comedy to the funny bits and amplifying to uncertainty of the thriller sequences (there is a shot I'd hate to describe for fear of spoiling it, in which we have to make sense of two planes of action separated by a sheet of glass, and the further back plane also is divided into a left and right; it's already a tense moment, as we wait to see if a character is spotted being in the wrong place, and the amount of effort it takes to look at the image makes it more tense still). It's a film that does more than anything in quite some time to underscore the relationship between form and content - to erase any distinction between the two. The way that scenes are staged and the story being told are inseparable, our emotional reaction to the one being conditioned and focused by the other. It is the sort of thing that only a filmmaker in full command of all his powers could possibly make, and even if I don't think the whole experience is quite as fresh and exhilarating as e.g. Mother, I do think that Bong himself is at the very peak of his powers of crafting expressive visuals in Parasite. If he wasn't already one of our leading filmmakers, this would be more than enough to anoint him thus.