These creatures are nothing but pure, motorized instinct

Also check out my review of the Italian cut

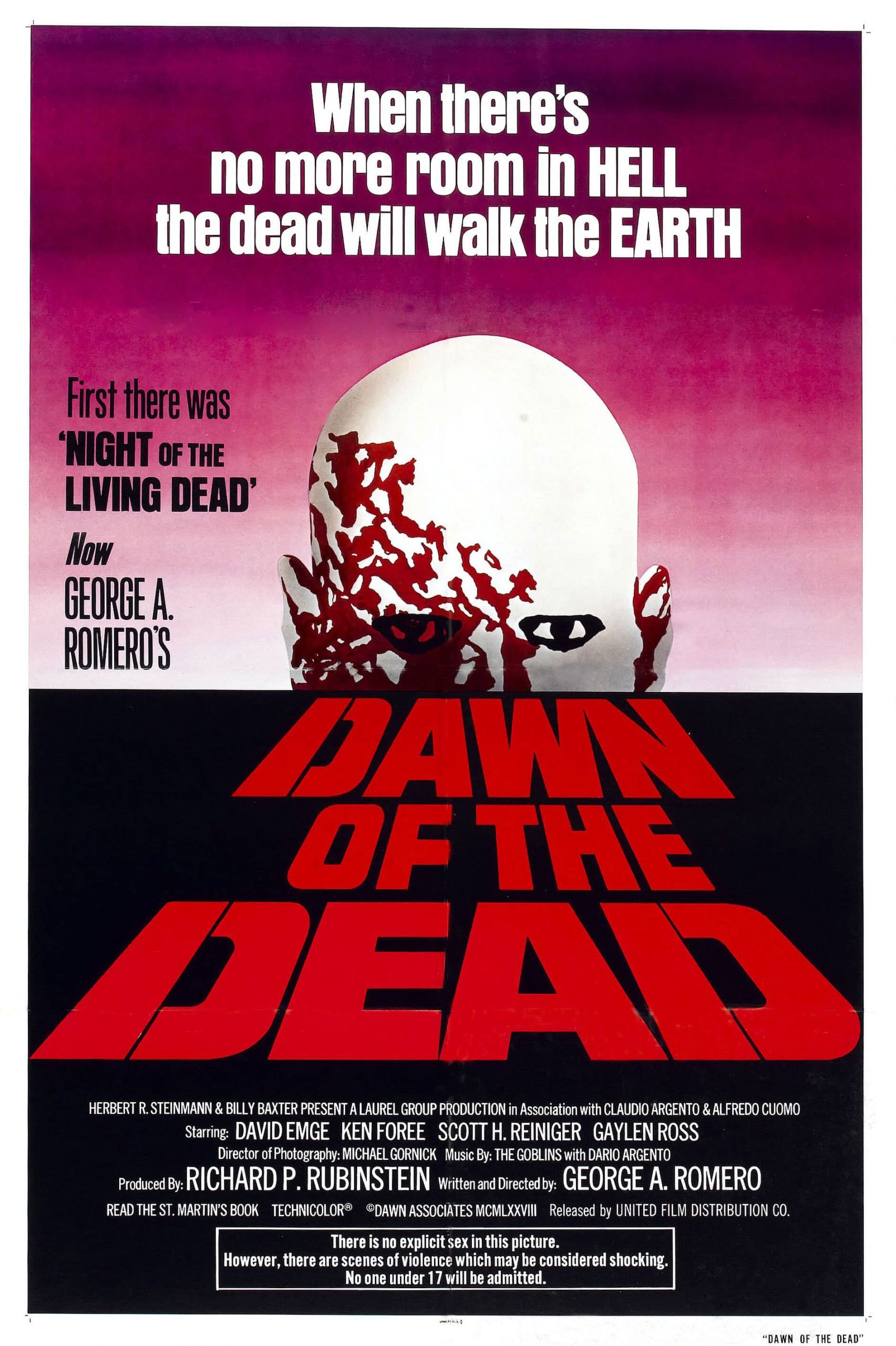

It is a common observation and an accurate one that independent Pittsburgh-based director George A. Romero invented the modern zombie film more or less entirely out of thin air with 1968's Night of the Living Dead. But I think the reason that the zombie film turned into an unstoppable subgenre that remains lively (as it were) after several uninterrupted decades owes more to another Romero film, from ten years later: Dawn of the Dead, a kind of thematic sequel. For while Night inspired its share of copycats throughout the 1970s (as a film will when it demonstrates that kind of return-on-investment for a production that literally anybody with access to a camera and a butcher shop could throw together), Dawn inspired a bona-fide cottage industry, particularly in Europe. This despite being considerably harder to ruthlessly copy: instead of Night's combination of a single family house and offal, Dawn draws much of its success from one of the most idiosyncratic locations in genre film history, and the irreplaceable effects makeup artist Tom Savini, better than anybody else in his generation at getting gut-churning results out of hardly any money.

The most copy-resistant element of the film, though, is the same that Night had: it is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking. These are, indeed, both two of the very best horror films ever made, the crown jewels of an exceptionally strong career. Between the two Dead films, Romero had directed four features, a featurette that was shelved by its financiers, and a series of sports documentaries on television, and two of those features - The Crazies from 1973 and Martin from 1977 (the film where he first worked with Savini) - are essential works in their own right. Even so, the ten years separating Romero's first two zombie films saw his career stumbling from flop. I cannot say if his return to the genre where he'd made his explosive debut was thus a desperation gambit, hoping that if he gave the audience what they wanted, he'd become successful and be able to keep working. Or maybe it's the other way around: he straggled for ten years not revisiting his biggest success because he was too true to his artistic vision to shit out a cash-in, but returned to it only when he had an idea worth of Night.

And this we certainly have. The titles give the game away: where the first film presents the first arrival of an inexplicable plague of dead bodies reanimating to devour the flesh of live humans, Dawn is about how those ghouls* rise to take the planet away from us. Leading, naturally enough, to a Day of the Dead seven years later (I somewhat-seriously believe that the increasingly limited artistic appeal of Romero's three Dead movies from the 2000s is in part because he abandoned the "time of day" metaphor). Of course, the first film took place in what was unabashedly 1968, and now, three weeks later, it's unabashedly 1978, but as a director viscerally allergic to subtle metaphors, Romero wants to make entirely certain that we understand how Dawn of the Dead is working as social commentary. Maybe it's even fair to say that it's working first and foremost as social commentary, doing the grubby work of being a horror-thriller about surviving (or not) a zombie onslaught only in the margins of a tale of human pettiness and consumerist avarice.

The whole thing feels, in a way, like a massively plus-sized version of Night of the Living Dead: strip away the details, and they're both about how a group of survivors coalesces and finds a way to lock themselves inside an apparently secure building. And here they would likely be able to survive the zombies, if not for their basic human stupidity. It's not group in-fighting this time around, but our heroes still fuck up, and that's why they die, and this gets us to the theme that Romero returned to in every one of his zombie films: we would all be fine and survive if we weren't greedy, selfish assholes. That gets inflected by his views on contemporary America with every film in the series through at least Land of the Dead in 2004 (I have not found it in me to ever re-watch 2007's Diary of the Dead nor 2009's Survival of the Dead), and in Dawn there are two big targets, unevenly distributed in the film.

The opening scene drops us right into a frenzied panic as martial law descends upon the city: there is an evacuation order in place, and plenty of violent conflicts between the police and residents over the prosecution of those orders. We begin the film in the chaos of a newsroom attempting to cover those conflicts with no concern for the safety of its employees or audience, viewing this through the persons of Francine Parker (Gaylen Ross) and Stephen Andrews (David Emge), who've decided to get the hell out by stealing the station's traffic helicopter. It's a breathtaking opening, barely coherent and cut into a dizzying mess, by Romero himself (sort of - more on that below), giving us only a scrappy sense of what's going on, with the only voice rising above the din that of a scientist (David Crawford) declaring angrily to the anchor across from him that basic human sentimentality will get us all killed. This is the other theme Romero likes to tease throughout his zombie films: that nihilistic times call for nihilistic people. It's never voiced so bluntly as in this film - never a man to hide his themes, the writer-director is really open about them in Dawn of the Dead - and by presenting this cynical view of the world right front-and-center as the only thing to hang on to during a messy, confusing opening scene, it colors everything that happens for the whole movie. (Confusingly, throughout the rest of the film, similar sentiments will be espoused on an increasingly degraded broadcast signal by a different scientist, played by Richard France; while I assume there was some particular reason for these to be two different characters, it feels needlessly cluttered).

We then leap over to a pitched battle between a group of locals who've holed themselves up against the evacuation order and the police attempting to evacuate them with extreme prejudice; things are already fraught when oone particular racist cop (Jim Baffico) decided to open fire on the predominately Hispanic crowd, and from here it's all more chaos that ends when a white officer, Roger DiMarco (Scott H. Reinger) and a black officer, Peter Washington (Ken Foree) agree that they, too, need to get the hell out of town, after they're called upon to kill a whole basementful of newly-awakened zombies. Roger, it turns out, is friends with Stephen, and has already made plans to escape with him and Francine; one more passenger won't be too much of a hassle, and soon all four are flying low over the zombie-covered Pennsylvania countryside.

Thus ends Act I, in which Romero finishes working The Crazies out of his system by examining the terrifying breakdown of structures in times of crisis, and the violent, destructive attempt by those dying structures to assert their authority in times of crisis. Other than to set a certain grim mood, this ends up having very little to do with the rest of Dawn of the Dead, which can be summarised with admirable simplicity: zombies in a shopping mall. Romero got the idea when visiting the massive Monroeville Mall, the largest indoor mall in the United States when it opened in 1969; it provided both a good space for a narrative to function (a highly secure third floor of administrative offices, literally everything necessary to support human life on the bottom two floors), and a ready-made metaphor for a soul-dead consumer culture that had, in Romero's reckoning, gripped the country as the dreams of the '60s curdled and died, leaving behind only the atomization of the Me Decade.

In Romero's 127-minute cut of the film, this message is achieved in large part through the very odd structure of the narrative. The foursome arrives at the mall and quickly figures out how to clear the zombies out - Roger is bitten in this process - and then proceeds to spend a solid 40 minutes or so just fucking around, enjoying all the amenities that this preposterously over-stuffed mall can offer. It is a very long 40 minutes, and thereon hangs a couple of tales.

First, there's the curious parallel life of the film. Dawn of the Dead was made for hardly any money, a mere million and a half dollars (and turned an enormous profit as a result), but it was still more than Romero could raise on his own. Fortunately, he had a very influential celebrity fan in the form of Italian horror director Dario Argento, who helped secure financing and distribution. The wrinkle to this is that Argento would have a free hand to recut the film for "European tastes", meaning that Romero only got his cut in the American market. Argento's cuts, with tiny variations for different markets), all ran several minutes shorter than Romero's final cut, which was already a great deal shorter than the loose 139-minute cut that premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. And that's after that Argento added back in a great deal of gore that Romero included in neither of his cuts. Argento also scrapped the library music that made up a decent portion of the film's soundtrack, replacing it with original music by his favored band Goblin (the 127-minute cut also includes quite a bit of Goblin's score). These changes all served to make the film much faster and punchier, while removing the sometimes glib, and sometimes brilliantly glib humor that the library music imparted. Argento's cut was released under the title (translated to each local language) Zombie: Dawn of the Dead, and it's not nearly as good as Romero's and all because it strips out that wandering 40 minutes.

Second, while this is at heart the same basic idea as Night, the two films feel as different as they possibly could. Night is unrelenting and driven, screaming forward at top speed for 96 minutes of aggressive terror. It does one thing, and it does it hard. Dawn is indulgent and grandiose, expansive in its world-building, and fascinated by the weird enclosed world of Monroeville Mall, captured by cinematographer Michael Gornick as a box full of jarring artificial colors and unearthly flat lighting. That long pause, that garish color and that sense of scope all set this film apart from its predecessor, but the long pause is the one that matters. Simply put, you could almost forget you're watching a zombie film - there are hardly any zombies in this sequence, and there are none of Savini's elaborately disgusting and hugely impressive gore effects - I am always taken aback to realise just how late in the film it is that another gang of roving humans finally arrives to destablise the situation, in part because some of our survivors make twitchy, disastrous choices about what to do with them.

And from that point, we're off the races, with machetes and squibs and all, leading to the least-downbeat ending in any Romero zombie film, which still leaves it ample room to be extremely downbeat. The ending is terrific, a geyser of apocaylptic violence in which everybody just gets to killing everyone else, while tinny muzak plays over the mall's loudspeakers, including a goofy carnivalesque march that I refuse to believe would ever play in a shopping mall, but it instantly does the necessary work of transforming the zombie hordes into droning clowns. And this is, in and of itself, an important part of Romero's game: more than in any of his other films, the zombies simply don't seem like that much of a threat here, which makes it all the clearer that the primary cause of human woes in this cosmos is human stupidity.

And, much more to the point, human greed. In a writerly note so barbaric that it goes all the way back around to charming, Romero feeds Peter two variant lines that go something like "these soulless monsters have come to this mall to mindlessly wander through its stores staring emptily at consumer goods, just like when they were soulless people. Because the mall and shopping were their religion". I exaggerate, but not by nearly as much as I wish I was. The point is, Dawn of the Dead is About Consumerism. And even capitalising those words doesn't make it clear how very much it is About that. Amazingly, this all goes down smooth as silk; I think it is because the film is doing so many other things atop it, and because Romero and Gornick really do capture something extraordinary about the look of a late-'70s mall as place that's hideous and tacky, but also marvelously large and airy and palatial in a weirdly exhilarating way, and because although the overall pacing of the middle of the film is glacially slow, Romero cuts individual scenes to crackle with the wavering amount of tension and/or camaraderie between the characters (who largely remain in the pairs that they arrived in).

So anyway, back to that long, languid middle, where this white-knuckle terror film about the dead spilling out of Hell jams on the brakes and lets the engine idle for about a third of the overall running time. This is frustating as hell, and it is obviously on purpose. The first thing our heroes do, once they've secured the mall, is to go on a shopping spree - a looting spree, really, but the subtleties in how its cut and staged compared to the other gang doing the same thing suggests we're meant to find it fun and exciting. And this is, of course, ridiculous and pointless. Consumer culture died with the rest of culture. All we're seeing is mindless habit, the joy of acquiring stuff in a world where stuff makes no sense. Romero views every bit of this with open contempt, and to drive his point home, he makes us wait, and watch, and dither around, until we're just as bored with the limits of this world as the characters are. He makes us sit around that mall until all of its charms and odd appeal have boiled away, revealing how very shallow the whole thing was in the first place.

It's about as subtle as getting scalped by a helicopter blade, but treat the movie as a parable, and it works well enough. And certainly, we're invited to treat it that way, though that part of the film is intermixed with enough character beats dedicated to fleshing out the relationships between the leads that it also feels a bit warmer and with more momentum than simply calling it a parable allows for. This is, maybe, the Romero touch: wrap a lecturing theme around strong characters that we instantly like, even knowing that they will surely die horribly and make us feel awful. In so doing, make both the lecture and the characters feel all the better.

And this is, to be clear, in addition to how fantastic Dawn is at the basic task of being a violent, terrifying horror movie. Savini would later do great things with higher budgets than this, but I am certain this is my favorite one of his films: the amount of pure, unmitigated show-off razzle-dazzle is delightful. So is the film's menacing slow burn, with Goblin's music putting in an appearance every so often to jolt us back into tension as the comic bits pile up. It's so full of tiny shifts in tone like that, that simply trying to figure out if we're scared, bored, or grinning is a bit tiring, leaving us fully vulnerable to the sudden, unstoppable rush of catastrophic violence and mayhem in the last half-hour. Basically, Romero has it all ways: slapping us in the face with his angry, socially-conscious theme, making us fall in love with these doomed characters, and playing to the groundlings who just want to see viscera, and he does it all constantly, and very well. I get why one might prefer the merciless focus of Night, the more intense and watchable movie, but honestly, this film's "the world in a shopping mall" sprawl appeals to me just as much, and when I find myself thinking of any old random zombie movie, it's almost always this one. Genre cinema simply doesn't get bigger and bolder and more ambitious than this.

*Romero finally uses the word "zombie" this time around, a decade of imitators having decided that's what he meant in the first place, thus forever banishing actual zombies from our cinema screens.

It is a common observation and an accurate one that independent Pittsburgh-based director George A. Romero invented the modern zombie film more or less entirely out of thin air with 1968's Night of the Living Dead. But I think the reason that the zombie film turned into an unstoppable subgenre that remains lively (as it were) after several uninterrupted decades owes more to another Romero film, from ten years later: Dawn of the Dead, a kind of thematic sequel. For while Night inspired its share of copycats throughout the 1970s (as a film will when it demonstrates that kind of return-on-investment for a production that literally anybody with access to a camera and a butcher shop could throw together), Dawn inspired a bona-fide cottage industry, particularly in Europe. This despite being considerably harder to ruthlessly copy: instead of Night's combination of a single family house and offal, Dawn draws much of its success from one of the most idiosyncratic locations in genre film history, and the irreplaceable effects makeup artist Tom Savini, better than anybody else in his generation at getting gut-churning results out of hardly any money.

The most copy-resistant element of the film, though, is the same that Night had: it is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking. These are, indeed, both two of the very best horror films ever made, the crown jewels of an exceptionally strong career. Between the two Dead films, Romero had directed four features, a featurette that was shelved by its financiers, and a series of sports documentaries on television, and two of those features - The Crazies from 1973 and Martin from 1977 (the film where he first worked with Savini) - are essential works in their own right. Even so, the ten years separating Romero's first two zombie films saw his career stumbling from flop. I cannot say if his return to the genre where he'd made his explosive debut was thus a desperation gambit, hoping that if he gave the audience what they wanted, he'd become successful and be able to keep working. Or maybe it's the other way around: he straggled for ten years not revisiting his biggest success because he was too true to his artistic vision to shit out a cash-in, but returned to it only when he had an idea worth of Night.

And this we certainly have. The titles give the game away: where the first film presents the first arrival of an inexplicable plague of dead bodies reanimating to devour the flesh of live humans, Dawn is about how those ghouls* rise to take the planet away from us. Leading, naturally enough, to a Day of the Dead seven years later (I somewhat-seriously believe that the increasingly limited artistic appeal of Romero's three Dead movies from the 2000s is in part because he abandoned the "time of day" metaphor). Of course, the first film took place in what was unabashedly 1968, and now, three weeks later, it's unabashedly 1978, but as a director viscerally allergic to subtle metaphors, Romero wants to make entirely certain that we understand how Dawn of the Dead is working as social commentary. Maybe it's even fair to say that it's working first and foremost as social commentary, doing the grubby work of being a horror-thriller about surviving (or not) a zombie onslaught only in the margins of a tale of human pettiness and consumerist avarice.

The whole thing feels, in a way, like a massively plus-sized version of Night of the Living Dead: strip away the details, and they're both about how a group of survivors coalesces and finds a way to lock themselves inside an apparently secure building. And here they would likely be able to survive the zombies, if not for their basic human stupidity. It's not group in-fighting this time around, but our heroes still fuck up, and that's why they die, and this gets us to the theme that Romero returned to in every one of his zombie films: we would all be fine and survive if we weren't greedy, selfish assholes. That gets inflected by his views on contemporary America with every film in the series through at least Land of the Dead in 2004 (I have not found it in me to ever re-watch 2007's Diary of the Dead nor 2009's Survival of the Dead), and in Dawn there are two big targets, unevenly distributed in the film.

The opening scene drops us right into a frenzied panic as martial law descends upon the city: there is an evacuation order in place, and plenty of violent conflicts between the police and residents over the prosecution of those orders. We begin the film in the chaos of a newsroom attempting to cover those conflicts with no concern for the safety of its employees or audience, viewing this through the persons of Francine Parker (Gaylen Ross) and Stephen Andrews (David Emge), who've decided to get the hell out by stealing the station's traffic helicopter. It's a breathtaking opening, barely coherent and cut into a dizzying mess, by Romero himself (sort of - more on that below), giving us only a scrappy sense of what's going on, with the only voice rising above the din that of a scientist (David Crawford) declaring angrily to the anchor across from him that basic human sentimentality will get us all killed. This is the other theme Romero likes to tease throughout his zombie films: that nihilistic times call for nihilistic people. It's never voiced so bluntly as in this film - never a man to hide his themes, the writer-director is really open about them in Dawn of the Dead - and by presenting this cynical view of the world right front-and-center as the only thing to hang on to during a messy, confusing opening scene, it colors everything that happens for the whole movie. (Confusingly, throughout the rest of the film, similar sentiments will be espoused on an increasingly degraded broadcast signal by a different scientist, played by Richard France; while I assume there was some particular reason for these to be two different characters, it feels needlessly cluttered).

We then leap over to a pitched battle between a group of locals who've holed themselves up against the evacuation order and the police attempting to evacuate them with extreme prejudice; things are already fraught when oone particular racist cop (Jim Baffico) decided to open fire on the predominately Hispanic crowd, and from here it's all more chaos that ends when a white officer, Roger DiMarco (Scott H. Reinger) and a black officer, Peter Washington (Ken Foree) agree that they, too, need to get the hell out of town, after they're called upon to kill a whole basementful of newly-awakened zombies. Roger, it turns out, is friends with Stephen, and has already made plans to escape with him and Francine; one more passenger won't be too much of a hassle, and soon all four are flying low over the zombie-covered Pennsylvania countryside.

Thus ends Act I, in which Romero finishes working The Crazies out of his system by examining the terrifying breakdown of structures in times of crisis, and the violent, destructive attempt by those dying structures to assert their authority in times of crisis. Other than to set a certain grim mood, this ends up having very little to do with the rest of Dawn of the Dead, which can be summarised with admirable simplicity: zombies in a shopping mall. Romero got the idea when visiting the massive Monroeville Mall, the largest indoor mall in the United States when it opened in 1969; it provided both a good space for a narrative to function (a highly secure third floor of administrative offices, literally everything necessary to support human life on the bottom two floors), and a ready-made metaphor for a soul-dead consumer culture that had, in Romero's reckoning, gripped the country as the dreams of the '60s curdled and died, leaving behind only the atomization of the Me Decade.

In Romero's 127-minute cut of the film, this message is achieved in large part through the very odd structure of the narrative. The foursome arrives at the mall and quickly figures out how to clear the zombies out - Roger is bitten in this process - and then proceeds to spend a solid 40 minutes or so just fucking around, enjoying all the amenities that this preposterously over-stuffed mall can offer. It is a very long 40 minutes, and thereon hangs a couple of tales.

First, there's the curious parallel life of the film. Dawn of the Dead was made for hardly any money, a mere million and a half dollars (and turned an enormous profit as a result), but it was still more than Romero could raise on his own. Fortunately, he had a very influential celebrity fan in the form of Italian horror director Dario Argento, who helped secure financing and distribution. The wrinkle to this is that Argento would have a free hand to recut the film for "European tastes", meaning that Romero only got his cut in the American market. Argento's cuts, with tiny variations for different markets), all ran several minutes shorter than Romero's final cut, which was already a great deal shorter than the loose 139-minute cut that premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. And that's after that Argento added back in a great deal of gore that Romero included in neither of his cuts. Argento also scrapped the library music that made up a decent portion of the film's soundtrack, replacing it with original music by his favored band Goblin (the 127-minute cut also includes quite a bit of Goblin's score). These changes all served to make the film much faster and punchier, while removing the sometimes glib, and sometimes brilliantly glib humor that the library music imparted. Argento's cut was released under the title (translated to each local language) Zombie: Dawn of the Dead, and it's not nearly as good as Romero's and all because it strips out that wandering 40 minutes.

Second, while this is at heart the same basic idea as Night, the two films feel as different as they possibly could. Night is unrelenting and driven, screaming forward at top speed for 96 minutes of aggressive terror. It does one thing, and it does it hard. Dawn is indulgent and grandiose, expansive in its world-building, and fascinated by the weird enclosed world of Monroeville Mall, captured by cinematographer Michael Gornick as a box full of jarring artificial colors and unearthly flat lighting. That long pause, that garish color and that sense of scope all set this film apart from its predecessor, but the long pause is the one that matters. Simply put, you could almost forget you're watching a zombie film - there are hardly any zombies in this sequence, and there are none of Savini's elaborately disgusting and hugely impressive gore effects - I am always taken aback to realise just how late in the film it is that another gang of roving humans finally arrives to destablise the situation, in part because some of our survivors make twitchy, disastrous choices about what to do with them.

And from that point, we're off the races, with machetes and squibs and all, leading to the least-downbeat ending in any Romero zombie film, which still leaves it ample room to be extremely downbeat. The ending is terrific, a geyser of apocaylptic violence in which everybody just gets to killing everyone else, while tinny muzak plays over the mall's loudspeakers, including a goofy carnivalesque march that I refuse to believe would ever play in a shopping mall, but it instantly does the necessary work of transforming the zombie hordes into droning clowns. And this is, in and of itself, an important part of Romero's game: more than in any of his other films, the zombies simply don't seem like that much of a threat here, which makes it all the clearer that the primary cause of human woes in this cosmos is human stupidity.

And, much more to the point, human greed. In a writerly note so barbaric that it goes all the way back around to charming, Romero feeds Peter two variant lines that go something like "these soulless monsters have come to this mall to mindlessly wander through its stores staring emptily at consumer goods, just like when they were soulless people. Because the mall and shopping were their religion". I exaggerate, but not by nearly as much as I wish I was. The point is, Dawn of the Dead is About Consumerism. And even capitalising those words doesn't make it clear how very much it is About that. Amazingly, this all goes down smooth as silk; I think it is because the film is doing so many other things atop it, and because Romero and Gornick really do capture something extraordinary about the look of a late-'70s mall as place that's hideous and tacky, but also marvelously large and airy and palatial in a weirdly exhilarating way, and because although the overall pacing of the middle of the film is glacially slow, Romero cuts individual scenes to crackle with the wavering amount of tension and/or camaraderie between the characters (who largely remain in the pairs that they arrived in).

So anyway, back to that long, languid middle, where this white-knuckle terror film about the dead spilling out of Hell jams on the brakes and lets the engine idle for about a third of the overall running time. This is frustating as hell, and it is obviously on purpose. The first thing our heroes do, once they've secured the mall, is to go on a shopping spree - a looting spree, really, but the subtleties in how its cut and staged compared to the other gang doing the same thing suggests we're meant to find it fun and exciting. And this is, of course, ridiculous and pointless. Consumer culture died with the rest of culture. All we're seeing is mindless habit, the joy of acquiring stuff in a world where stuff makes no sense. Romero views every bit of this with open contempt, and to drive his point home, he makes us wait, and watch, and dither around, until we're just as bored with the limits of this world as the characters are. He makes us sit around that mall until all of its charms and odd appeal have boiled away, revealing how very shallow the whole thing was in the first place.

It's about as subtle as getting scalped by a helicopter blade, but treat the movie as a parable, and it works well enough. And certainly, we're invited to treat it that way, though that part of the film is intermixed with enough character beats dedicated to fleshing out the relationships between the leads that it also feels a bit warmer and with more momentum than simply calling it a parable allows for. This is, maybe, the Romero touch: wrap a lecturing theme around strong characters that we instantly like, even knowing that they will surely die horribly and make us feel awful. In so doing, make both the lecture and the characters feel all the better.

And this is, to be clear, in addition to how fantastic Dawn is at the basic task of being a violent, terrifying horror movie. Savini would later do great things with higher budgets than this, but I am certain this is my favorite one of his films: the amount of pure, unmitigated show-off razzle-dazzle is delightful. So is the film's menacing slow burn, with Goblin's music putting in an appearance every so often to jolt us back into tension as the comic bits pile up. It's so full of tiny shifts in tone like that, that simply trying to figure out if we're scared, bored, or grinning is a bit tiring, leaving us fully vulnerable to the sudden, unstoppable rush of catastrophic violence and mayhem in the last half-hour. Basically, Romero has it all ways: slapping us in the face with his angry, socially-conscious theme, making us fall in love with these doomed characters, and playing to the groundlings who just want to see viscera, and he does it all constantly, and very well. I get why one might prefer the merciless focus of Night, the more intense and watchable movie, but honestly, this film's "the world in a shopping mall" sprawl appeals to me just as much, and when I find myself thinking of any old random zombie movie, it's almost always this one. Genre cinema simply doesn't get bigger and bolder and more ambitious than this.

*Romero finally uses the word "zombie" this time around, a decade of imitators having decided that's what he meant in the first place, thus forever banishing actual zombies from our cinema screens.