Sunshine almost all the time makes me cry

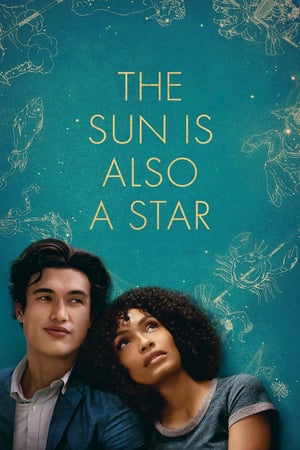

The Sun Is Also a Star has no reason to be good at all: the teen YA romance adaptation, as a genre, is not one that has ever demonstrated a particularly robust correlation between quality and financial success, just so long as the book has a big enough fanbase and the filmmakers avoid doing too much to screw it up. Which is apparently not something that director Ry Russo-Young and screenwriter Tracy Oliver were able to accomplish, given the film's unenthusiastic word-of-mouth and anemic box office returns. But they've done something better: they've made somewhat hokey, unbelievable material into something thoughtful and artful. "Artful" by the standards of movies designed from the ground-up for teenagers, to be sure - it's a bit stiff and overdone, but in a way meant to be grasped by people who probably haven't ever seen this kind of thing before.

Before we can get into any of that, though, the elephant in the room: even if The Sun and So On has some unusually sophisticated filmmaking for its genre, that's maybe not even enough to call it a good film. After all, what is the ultimate point of any romantic film, teen-oriented or otherwise, if not to sweep us away with the emotions of its leads, and stoke our desire to see them end up together? And this is the great, big, insoluble problem we have in front of us: the central couple here doesn't work at all. This is not, individually, the fault of either one of the actors. Yara Shahidi, chiefly known for her work on the TV show Black-ish, isn't a natural movie star, but the film isn't looking for a movie-star turn; it wants Shahidi's character, Natasha Kingsley, to have a lost, in-over-her-head vibe, and a stubborn resolute quality that's not enough to make a hopeless situation any less hopeless. She spends the two days and one night of the film trying desperately to find any legal toehold to keep her family from being deported back to Jamaica at the end of the second afternoon, and the film needs an actor who can be highly personal and distinct in that role, but also one who can seem plausibly defeated and desperate by the enormity of the situation facing her. Shahidi fits that faultlessly, making it very clear who Natasha is whenever she's not in the middle of this terribly heavy crisis, but also making the weight of that crisis come across in all of her slow, dragging movements.

Her opposite number is Charles Melton, playing Daniel Bae, whose situation isn't nearly as interesting: he's a first-generation Korean-American whose parents are extremely eager for him to get into Dartmouth, there to study medicine. But he wants to write. On this particular day, he's meeting with an alumnus for the pro forma ritual of the admissions interview, and is trying to will himself into being enthusiastic and alive for the process. It's a stock role, and Melton gives a stock performance, but he acquits himself perfectly well, and he even makes the sluggish subplot involving Daniel's brother, played by Jake Choi, feel like it's at least grounded in human emotions, if not dramatic necessity.

The problem comes when these two combine. What happens is that Daniel stops Natasha from walking out into bustling New York traffic, and he takes her to a coffee shop to calm down. There, they outline their respective worldviews: she is an arch-materialist who believes in nothing that cannot be measured and mathematically proven, whereas he is a romantic fatalist. Naturally assuming that their meet-cute can only be a sign from the universe, he wagers that he can make her fall in love with him, disproving her contention that love itself does not exist. Quicker than you can say Before Sunrise, the two of them spend most of the next 24 hours strolling around New York, swapping worldviews, and Natasha is generally very good at somewhat hiding the fact that she hopes Daniel will win their bet.

Cute enough, if a bit obvious, but here's the thing: Melton is nine years old than Shahidi. Nine very visible years. So we basically end up with two characters from two entirely different forms of teen romance. Natasha is, befitting her personality, from a somewhat raw and realistic take on the life of an urban-dwelling teenager, one that's sympathetic to the absurdities teenagers make up for themselves, especially teenagers too smart for their own good, but which still recognises them as absurd. Melton is from the kind of over-the-top soap opera where every high-schooler looks old enough that they've started having serious conversation with their financial planner about their 401(k). Hell, if that's meant to be a bit of meta-commentary about how the two characters view romance, good on the film for thinking about the affective value of casting. It doesn't change the fact that the movie wants us to root for the romantic success of a coupling in which the male lead is so clearly older than the female lead that it doesn't feel like two lost 18-year-olds finding each other, it feels like one lost 18-year-old being menaced by one incredibly sleazy day trader who probably has the age-of-consent laws for all 50 states memorised. This is what happens when "the Riverdale fanbase thinks he's dreamy" is allowed to triumph over any kind of consideration of how actors play together. It makes it frankly impossible to root for the romance, and once you've taken that away, there's precious little left here.

And yet, I still find myself thinking kindly on the film. Again, it wants to be better than it needs to be, and that sort of thing always deserves a bit of our respect. Russo-Young isn't turning this into some kind of ultra-formalist experiment, but she is awfully aware of the impact style can have on our understanding of the characters and their worldviews, and so it is that The Sun Is Also a Star boasts a very visible, aggressive motif of what I can only think to call expository montages. Every so often - I didn't count how many times, but it's frequent, and it doesn't let up - either Natasha or Daniel will mention some concept, either to each other or to us (it's a very narration-heavy movie), and for a minute or two the film erupts into a sort of manic slideshow, with flashbacks, stock footage, file photos, and onscreen text flurrying across as they speak, visualising the subject they're talking about: not always directly illustrating their words, either, but often providing something of a complimentary narrative that fleshes out the topic with more global context. It happens for all sorts of things, from astrophysics to the role of Korean immigrants in the United States' economy, and every time it's slightly different in terms of how it's structured, but always with the same caffeinated rhythm. The first couple of times this happened, I was damned annoyed. By the seventh or eighth time, it felt like the most cunning way possible to directly visualise the way that teenagers in the late 2010s process the world: as a whirlwind of somewhat opaque images, arranged roughly into a narrative that only makes sense because we're encountering them in an order. It is the philosophical discussion for people whose understanding of the world is half Wikipedia, half Instagram, in other words, and it somehow becomes a very charming embodiment of the way that, for all these two people act very worldly and articulate, they're still basically just kids trying to operate from a limited perspective.

The other thing the film has in its pocket is that it's immoderately well-shot. Cinematographer Autumn Durald has done something magical and weird with the overall aesthetic of this film: she's found a way to make golden hour look not beautiful. Which doesn't sound like a triumph, but the success of the film's look lies in how particularly it captures a uniquely urban quality of light: the sense of everything being doused in golden yellows that feel more hot and hostile and unblinking than romantic and picturesque. Befitting a movie with "Sun" right there in the title, The Sun Is Also a Star almost makes it seem like the lighting is a sentient force, bearing down on the characters and making their world seem very lovely in a very impersonal way. It makes it feel, even more than the esoteric monologues, like the characters can't help but be aware that they are very tiny, insubstantial people in a huge city in an even huger world. While the script is guilty as all hell of forgetting about its immigration subplot, and often feels like it has no actual stakes, the look of the film brings those stakes back, by insisting upon the largeness of New York and the unfeelingness of the sun beating down on it.

Not a bad trick, and one that helps to make the film feel a bit deeper than the script always allows for. This is a film playing with a lot of ideas, more than it has room for, and it tends to drop them (which is a slightly terrible thing for a work of art so pointedly looking at a major political topic to do). Somehow, the film's technique manages to at least somewhat bring back a sense of gravity and depth to the cumbersome philosophical dialogue, and imbue the characters with the rich intellectualism that the writing can't support. If we could find a way to bring that together with a pair of lovers that were actually worth rooting for, well, heck, we might even have a movie right there.

Before we can get into any of that, though, the elephant in the room: even if The Sun and So On has some unusually sophisticated filmmaking for its genre, that's maybe not even enough to call it a good film. After all, what is the ultimate point of any romantic film, teen-oriented or otherwise, if not to sweep us away with the emotions of its leads, and stoke our desire to see them end up together? And this is the great, big, insoluble problem we have in front of us: the central couple here doesn't work at all. This is not, individually, the fault of either one of the actors. Yara Shahidi, chiefly known for her work on the TV show Black-ish, isn't a natural movie star, but the film isn't looking for a movie-star turn; it wants Shahidi's character, Natasha Kingsley, to have a lost, in-over-her-head vibe, and a stubborn resolute quality that's not enough to make a hopeless situation any less hopeless. She spends the two days and one night of the film trying desperately to find any legal toehold to keep her family from being deported back to Jamaica at the end of the second afternoon, and the film needs an actor who can be highly personal and distinct in that role, but also one who can seem plausibly defeated and desperate by the enormity of the situation facing her. Shahidi fits that faultlessly, making it very clear who Natasha is whenever she's not in the middle of this terribly heavy crisis, but also making the weight of that crisis come across in all of her slow, dragging movements.

Her opposite number is Charles Melton, playing Daniel Bae, whose situation isn't nearly as interesting: he's a first-generation Korean-American whose parents are extremely eager for him to get into Dartmouth, there to study medicine. But he wants to write. On this particular day, he's meeting with an alumnus for the pro forma ritual of the admissions interview, and is trying to will himself into being enthusiastic and alive for the process. It's a stock role, and Melton gives a stock performance, but he acquits himself perfectly well, and he even makes the sluggish subplot involving Daniel's brother, played by Jake Choi, feel like it's at least grounded in human emotions, if not dramatic necessity.

The problem comes when these two combine. What happens is that Daniel stops Natasha from walking out into bustling New York traffic, and he takes her to a coffee shop to calm down. There, they outline their respective worldviews: she is an arch-materialist who believes in nothing that cannot be measured and mathematically proven, whereas he is a romantic fatalist. Naturally assuming that their meet-cute can only be a sign from the universe, he wagers that he can make her fall in love with him, disproving her contention that love itself does not exist. Quicker than you can say Before Sunrise, the two of them spend most of the next 24 hours strolling around New York, swapping worldviews, and Natasha is generally very good at somewhat hiding the fact that she hopes Daniel will win their bet.

Cute enough, if a bit obvious, but here's the thing: Melton is nine years old than Shahidi. Nine very visible years. So we basically end up with two characters from two entirely different forms of teen romance. Natasha is, befitting her personality, from a somewhat raw and realistic take on the life of an urban-dwelling teenager, one that's sympathetic to the absurdities teenagers make up for themselves, especially teenagers too smart for their own good, but which still recognises them as absurd. Melton is from the kind of over-the-top soap opera where every high-schooler looks old enough that they've started having serious conversation with their financial planner about their 401(k). Hell, if that's meant to be a bit of meta-commentary about how the two characters view romance, good on the film for thinking about the affective value of casting. It doesn't change the fact that the movie wants us to root for the romantic success of a coupling in which the male lead is so clearly older than the female lead that it doesn't feel like two lost 18-year-olds finding each other, it feels like one lost 18-year-old being menaced by one incredibly sleazy day trader who probably has the age-of-consent laws for all 50 states memorised. This is what happens when "the Riverdale fanbase thinks he's dreamy" is allowed to triumph over any kind of consideration of how actors play together. It makes it frankly impossible to root for the romance, and once you've taken that away, there's precious little left here.

And yet, I still find myself thinking kindly on the film. Again, it wants to be better than it needs to be, and that sort of thing always deserves a bit of our respect. Russo-Young isn't turning this into some kind of ultra-formalist experiment, but she is awfully aware of the impact style can have on our understanding of the characters and their worldviews, and so it is that The Sun Is Also a Star boasts a very visible, aggressive motif of what I can only think to call expository montages. Every so often - I didn't count how many times, but it's frequent, and it doesn't let up - either Natasha or Daniel will mention some concept, either to each other or to us (it's a very narration-heavy movie), and for a minute or two the film erupts into a sort of manic slideshow, with flashbacks, stock footage, file photos, and onscreen text flurrying across as they speak, visualising the subject they're talking about: not always directly illustrating their words, either, but often providing something of a complimentary narrative that fleshes out the topic with more global context. It happens for all sorts of things, from astrophysics to the role of Korean immigrants in the United States' economy, and every time it's slightly different in terms of how it's structured, but always with the same caffeinated rhythm. The first couple of times this happened, I was damned annoyed. By the seventh or eighth time, it felt like the most cunning way possible to directly visualise the way that teenagers in the late 2010s process the world: as a whirlwind of somewhat opaque images, arranged roughly into a narrative that only makes sense because we're encountering them in an order. It is the philosophical discussion for people whose understanding of the world is half Wikipedia, half Instagram, in other words, and it somehow becomes a very charming embodiment of the way that, for all these two people act very worldly and articulate, they're still basically just kids trying to operate from a limited perspective.

The other thing the film has in its pocket is that it's immoderately well-shot. Cinematographer Autumn Durald has done something magical and weird with the overall aesthetic of this film: she's found a way to make golden hour look not beautiful. Which doesn't sound like a triumph, but the success of the film's look lies in how particularly it captures a uniquely urban quality of light: the sense of everything being doused in golden yellows that feel more hot and hostile and unblinking than romantic and picturesque. Befitting a movie with "Sun" right there in the title, The Sun Is Also a Star almost makes it seem like the lighting is a sentient force, bearing down on the characters and making their world seem very lovely in a very impersonal way. It makes it feel, even more than the esoteric monologues, like the characters can't help but be aware that they are very tiny, insubstantial people in a huge city in an even huger world. While the script is guilty as all hell of forgetting about its immigration subplot, and often feels like it has no actual stakes, the look of the film brings those stakes back, by insisting upon the largeness of New York and the unfeelingness of the sun beating down on it.

Not a bad trick, and one that helps to make the film feel a bit deeper than the script always allows for. This is a film playing with a lot of ideas, more than it has room for, and it tends to drop them (which is a slightly terrible thing for a work of art so pointedly looking at a major political topic to do). Somehow, the film's technique manages to at least somewhat bring back a sense of gravity and depth to the cumbersome philosophical dialogue, and imbue the characters with the rich intellectualism that the writing can't support. If we could find a way to bring that together with a pair of lovers that were actually worth rooting for, well, heck, we might even have a movie right there.

Categories: love stories, summer movies, teen movies