Blockbuster History: Jeez, it's a lion!

Intermittently this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Disney's new version of The Lion King presents painstakingly animated photorealistic CGI lions milling about doing lion shit. This might seem like a lot of work to create inexpressive fake cats, but history teaches grave lessons about what happens when you put actual lions in your movie.

What, as the kids say, the actual fuck.

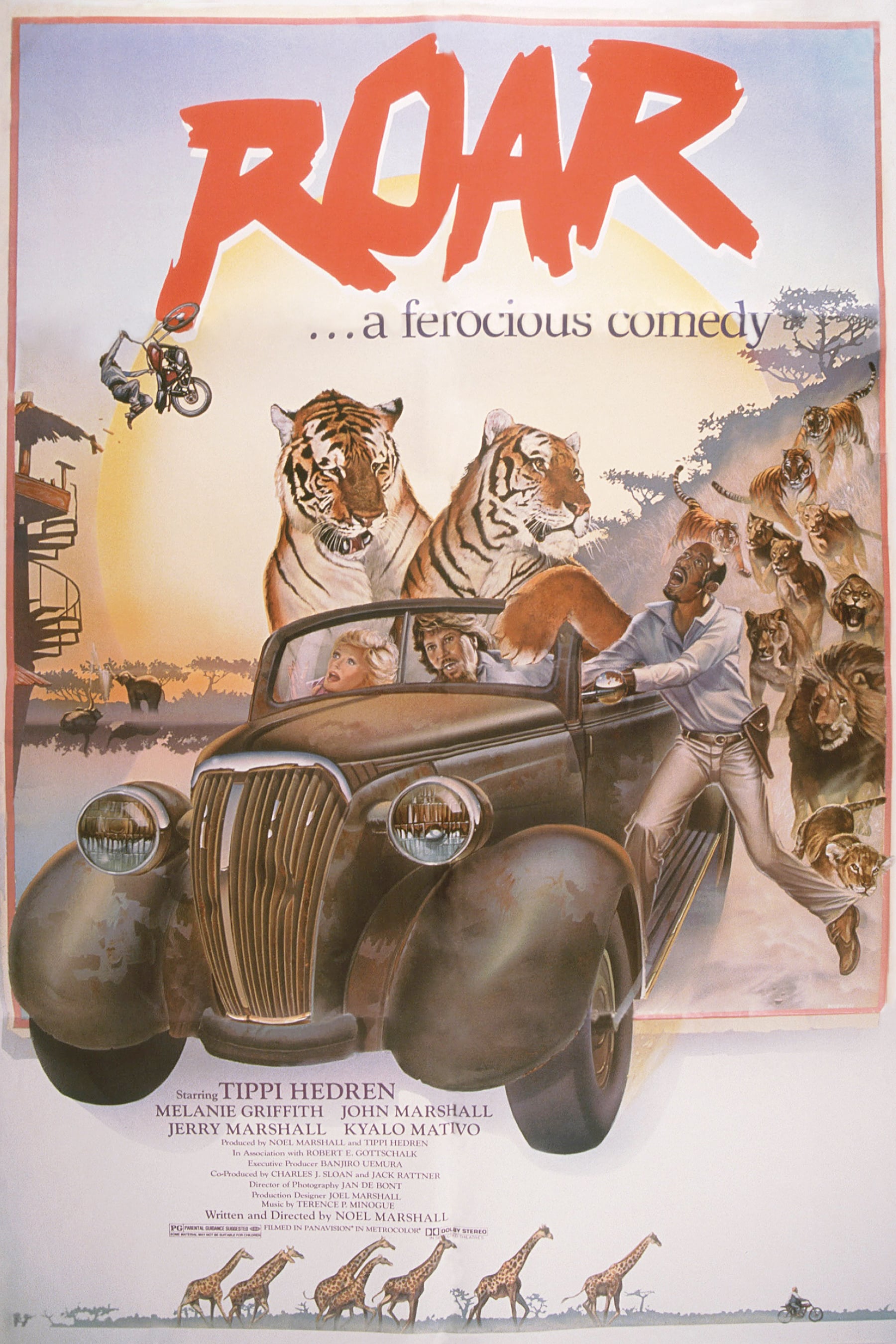

It is almost unnecessary to actually see Roar. Almost. The film itself isn't a patch on the story of its making; it's dithering and pointless, frankly, possessing barely any plot, nor any other intrinsic artistic merit other than its, shall we say, exceedingly intimate footage of lions and tigers and leopards going about the business of being big cats. And for that matter, I'm not sure that so much footage exists anywhere else that establishes just how much the Panthera species really do behave like ordinary housecats, with the same body language, facial expressions and all. So that's cool, if you're a cat person. But even this footage is somewhat compromised by the haplessness of the filmmaking, led as it was by first-and-only-time director Noel Marshall, an agent and sometime producer. Cinematographer Jan de Bont, making his first American film, knew what he was doing and you can frequently tell, but he's a bit hampered by the ad hoc nature of the shoot, plus the fact that his head was damn near removed over the course of production. But I am getting ahead of myself.

So anyway, Roar, as a movie, is a bit shapeless and held together with spit and prayer, and it is aggressively drab as a dramatic narrative. But this is one of those films where the stories of the film's production precede it; and even if they didn't, you would maybe be able to figure out what the living shit was going on just from the manic quality of the footage itself. For Roar is... well, there's just no other way of putting it than calling it the film where the husband-and-wife team (soon to be divorced, and I refuse to believe this movie wasn't a contributing factor) of Marshall and Tippi Hedren plopped themselves, three of their four children, and an entire film crew right in middle of 150 wild carnivores with no cages or body armor or anything, and just fucking filmed it.

Marshall and Hedren, you see, were the very special kind of psychopathic eccentrics you only get among the wealthy elite of California. After a trip to Mozambique in 1969, they were inspired by the plight of the local lion populations to make a movie in tribute to the wonderful animals, showcasing how peaceable and not-actually-threatening lions really were. And taking further inspiration from the sight of an abandoned plantation villa that had become the den for a lion pride, they decided that this film would substantially involve lions puttering about a human habitation, while the humans involved did their best to stay out of the way. Somewhere along the film's seven-year path from conception to shooting, Marshall and Hedren realised they could both substantially increase their feline cast and do the good work of helping threatened animals by collecting abandoned lions, tigers, leopard, pumas, elephants (!), and flamingos (!!), and letting them wander loose on the ranch the couple bought just for the purpose. Thus they'd have not just a memorable and important film bringing public attention to the importance of conserving and protecting the big cats, they'd also have a preserve all ready to go (and Hedren has, to her great credit, devoted much of her life in the years since to carrying out that mission, turning the ranch into the Shambala Preserve, maintained by the Roar Foundation).

Anyway, this didn't happen, because to the non-surprise of just about every living human not named Noel Marshall and Tippi Hedren, putting a film crew in the middle of 150 largely untrained big cats is unbelievably goddamn dangerous. Shooting Roar stretched out from a scheduled six months to over four years, as a simply tremendous number of crew members and virtually all of the cast suffered injuries from lacerations and scrapes to de Bont being literally scalped by a lion, requiring 220 stitches (in one of the most inspiring and/or mentally deranged "the show must go on" stories in history, de Bont returned to the production after recovering). Flooding, disease, and fires all took their toll on the feline cast, and there was, you will be just stunned to learn, an abnormally large amount of crew turnover as people began refusing to come back to set. Nobody died, which is both good and tremendously surprising.

This is, please understand, all visible in the movie. Most notoriously, Hedren's teenage daughter and future star Melanie Griffith had a substantial chunk of flesh torn off of her face in a shot that remains onscreen (and on the soundtrack). But even without the delirious, Romanesque spectacle of realising that the very realistic stage blood you see streaming down actors' faces and arms throughout the movie isn't stage blood, there's no shortage of jaw-dropping footage spread throughout the picture's 102 nerve-shredding minutes. Even without a single live human, cramming 150 big cats into a not especially large space would result in a lot of distinctly grumpy animals, and if Roar is genuinely, unironically good at anything, it's in providing a lion's-eye-view of lion behavior, as they wrestle, smack at each other, mercurially shifting from playful banter to obvious violence-prone annoyance in the blink of an eye. It's behavior that any house cat owner has seen dozens of times, for as any one of us could tell you, house cats are vicious little bastards, who would most undoubtedly eat you if it was in their interests to do so. The lions and tigers, as I said earlier, are basically just doing what any house cat would do; they just happen to be several hundred pounds bigger than a house cat, so they can actually make it count. And if Roar is genuinely, unironically good at a second thing, it's in making us understand just how big a lion or a tiger is, as we watch their massive, thick limbs wrap around human bodies, or even just as we see the stress on wooden floorboards underneath those meaty paws.

So far, so misguided - and, in its extraordinary way, so beautiful, as de Bont moves heaven and earth to find ways of capturing the animals in lovely diffused sunlight, when he and his camera crew can manage to stand still for long enough. But I have not more than gestured in the direction of Roar's most bonkers surprises of all. The thing is, Marshall and Hedren stuck to their guns. Even as the set of the film was turning into a blood-soaked thriller more viscerally terrifying than any slasher movie, the edit of Roar, and its merry, jaunty (and appallingly disjointed) musical score, composed by Terrence P. Minogue - plus the film's musical bookends, keening '70s folk rock songs with a vague but extremely sincere conservationist message, sung by Robert Hawk - absolutely insists that we're watching the mildly soppy, chipper family comedy that the couple first imagined eleven years before the nightmare ended. The opening titles are run through with upbeat, jokey mentions of the cats who deserved a co-writing and co-directing credit, the plot (such as it is) is fully of wacky slapstick misadventures, and there are several shots of lions with fresh blood caked in their manes. One of these things is very fucking much not like the others.

And that's where the surrealism comes. Roar's story is desperately flat: Hank (Noel Marshall) has been in Africa for three years tending to his conservation efforts, and his family comes to visit in despair of ever seeing him again - wife Madelaine (Hedren), sons John (John Marshall) and Jerry (Jerry Marshall) and daughter Melanie (Griffith). One presumes that the cast shares their names with the characters so that nobody had to pause to remember the script while they were screaming in mortal terror about the tiger with its jaws around their sibling's skull. Anyway, Hank isn't home; he's trying to stop a team of government-sponsored hunters who - get this conservative reactionary bullshit - think that it's extremely, world-historically foolish to let 150 big cats roam around your house, and someone might get hurt. Pshaw. He is accompanied in this by his Maasai sidekick Mativo (Kyalo Mativo), whose entire character arc consists of variations on "fuck this white people nonsense". This was at the actor's direct request, and for his extreme good sense, he was the sole member of the cast to receive no wounds from any of the animals.

Anyway, Madelaine and the kids arrive at Hank's villa, and are staggered to find it is overrun with lions. For the rest of the movie, they endeavor not to die, and it's a little bit confusing how they manage to be successful. Eventually, Hank comes back, and the whole family is moved to cuddle and pet and sleep next to the animals who just spent a day and night terrorising them at the most fundamental animal level of fear that we hairless savannah apes are capable of feeling when confronted with the bone-shaking roar of a hunting lion. But it's cute and wacky! You can tell because the music is silly! Ignore Melanie and Jerry's lacerating, shrill shrieks, erupting from their body at a pre-verbal level that no actor could possible fake!

I mean, kudos. Ku-fucking-dos. Marshall and Hedren wanted to make a movie about how swell lions were, and they made that movie, no matter how often they had to wipe the blood from their face to see what they were doing (Marshall took so many hits from the cats that he had to be hospitalised for gangrene. Gangrene. From a movie shoot). It is a light, upbeat story about how sweet and good the big kitties are, and no amount of visceral tension as we watch, helpless to stop, as various humans are turned into rubber-limbed playthings by animals who are never malicious. I mean, you can tell. They're not hunting. They're not angry. But my cat wasn't hunting or angry when she woke me up this morning by biting my ear, and she's only about 16 inches long, and that hurt like hell. Cats are assholes - big cats are big assholes. And Roar does absolutely superb work in capturing the heft and power of its feline cast, genuinely and successfully arguing for their majesty and vitalism. It does so in the most fucked-up, tonally surreal, viscerally unsettling way possible, but hey, the goal was to make me fall in love with lions, and I guess I did. At any rate, even having seen it twice now, I'm still struck by the sheer grandiose madness of the whole thing, and not bored for a minute, no matter how dopey and trifling the plot is. It is one of the truly singular one-offs in all of cinema history - thank the dear Lord for that!

What, as the kids say, the actual fuck.

It is almost unnecessary to actually see Roar. Almost. The film itself isn't a patch on the story of its making; it's dithering and pointless, frankly, possessing barely any plot, nor any other intrinsic artistic merit other than its, shall we say, exceedingly intimate footage of lions and tigers and leopards going about the business of being big cats. And for that matter, I'm not sure that so much footage exists anywhere else that establishes just how much the Panthera species really do behave like ordinary housecats, with the same body language, facial expressions and all. So that's cool, if you're a cat person. But even this footage is somewhat compromised by the haplessness of the filmmaking, led as it was by first-and-only-time director Noel Marshall, an agent and sometime producer. Cinematographer Jan de Bont, making his first American film, knew what he was doing and you can frequently tell, but he's a bit hampered by the ad hoc nature of the shoot, plus the fact that his head was damn near removed over the course of production. But I am getting ahead of myself.

So anyway, Roar, as a movie, is a bit shapeless and held together with spit and prayer, and it is aggressively drab as a dramatic narrative. But this is one of those films where the stories of the film's production precede it; and even if they didn't, you would maybe be able to figure out what the living shit was going on just from the manic quality of the footage itself. For Roar is... well, there's just no other way of putting it than calling it the film where the husband-and-wife team (soon to be divorced, and I refuse to believe this movie wasn't a contributing factor) of Marshall and Tippi Hedren plopped themselves, three of their four children, and an entire film crew right in middle of 150 wild carnivores with no cages or body armor or anything, and just fucking filmed it.

Marshall and Hedren, you see, were the very special kind of psychopathic eccentrics you only get among the wealthy elite of California. After a trip to Mozambique in 1969, they were inspired by the plight of the local lion populations to make a movie in tribute to the wonderful animals, showcasing how peaceable and not-actually-threatening lions really were. And taking further inspiration from the sight of an abandoned plantation villa that had become the den for a lion pride, they decided that this film would substantially involve lions puttering about a human habitation, while the humans involved did their best to stay out of the way. Somewhere along the film's seven-year path from conception to shooting, Marshall and Hedren realised they could both substantially increase their feline cast and do the good work of helping threatened animals by collecting abandoned lions, tigers, leopard, pumas, elephants (!), and flamingos (!!), and letting them wander loose on the ranch the couple bought just for the purpose. Thus they'd have not just a memorable and important film bringing public attention to the importance of conserving and protecting the big cats, they'd also have a preserve all ready to go (and Hedren has, to her great credit, devoted much of her life in the years since to carrying out that mission, turning the ranch into the Shambala Preserve, maintained by the Roar Foundation).

Anyway, this didn't happen, because to the non-surprise of just about every living human not named Noel Marshall and Tippi Hedren, putting a film crew in the middle of 150 largely untrained big cats is unbelievably goddamn dangerous. Shooting Roar stretched out from a scheduled six months to over four years, as a simply tremendous number of crew members and virtually all of the cast suffered injuries from lacerations and scrapes to de Bont being literally scalped by a lion, requiring 220 stitches (in one of the most inspiring and/or mentally deranged "the show must go on" stories in history, de Bont returned to the production after recovering). Flooding, disease, and fires all took their toll on the feline cast, and there was, you will be just stunned to learn, an abnormally large amount of crew turnover as people began refusing to come back to set. Nobody died, which is both good and tremendously surprising.

This is, please understand, all visible in the movie. Most notoriously, Hedren's teenage daughter and future star Melanie Griffith had a substantial chunk of flesh torn off of her face in a shot that remains onscreen (and on the soundtrack). But even without the delirious, Romanesque spectacle of realising that the very realistic stage blood you see streaming down actors' faces and arms throughout the movie isn't stage blood, there's no shortage of jaw-dropping footage spread throughout the picture's 102 nerve-shredding minutes. Even without a single live human, cramming 150 big cats into a not especially large space would result in a lot of distinctly grumpy animals, and if Roar is genuinely, unironically good at anything, it's in providing a lion's-eye-view of lion behavior, as they wrestle, smack at each other, mercurially shifting from playful banter to obvious violence-prone annoyance in the blink of an eye. It's behavior that any house cat owner has seen dozens of times, for as any one of us could tell you, house cats are vicious little bastards, who would most undoubtedly eat you if it was in their interests to do so. The lions and tigers, as I said earlier, are basically just doing what any house cat would do; they just happen to be several hundred pounds bigger than a house cat, so they can actually make it count. And if Roar is genuinely, unironically good at a second thing, it's in making us understand just how big a lion or a tiger is, as we watch their massive, thick limbs wrap around human bodies, or even just as we see the stress on wooden floorboards underneath those meaty paws.

So far, so misguided - and, in its extraordinary way, so beautiful, as de Bont moves heaven and earth to find ways of capturing the animals in lovely diffused sunlight, when he and his camera crew can manage to stand still for long enough. But I have not more than gestured in the direction of Roar's most bonkers surprises of all. The thing is, Marshall and Hedren stuck to their guns. Even as the set of the film was turning into a blood-soaked thriller more viscerally terrifying than any slasher movie, the edit of Roar, and its merry, jaunty (and appallingly disjointed) musical score, composed by Terrence P. Minogue - plus the film's musical bookends, keening '70s folk rock songs with a vague but extremely sincere conservationist message, sung by Robert Hawk - absolutely insists that we're watching the mildly soppy, chipper family comedy that the couple first imagined eleven years before the nightmare ended. The opening titles are run through with upbeat, jokey mentions of the cats who deserved a co-writing and co-directing credit, the plot (such as it is) is fully of wacky slapstick misadventures, and there are several shots of lions with fresh blood caked in their manes. One of these things is very fucking much not like the others.

And that's where the surrealism comes. Roar's story is desperately flat: Hank (Noel Marshall) has been in Africa for three years tending to his conservation efforts, and his family comes to visit in despair of ever seeing him again - wife Madelaine (Hedren), sons John (John Marshall) and Jerry (Jerry Marshall) and daughter Melanie (Griffith). One presumes that the cast shares their names with the characters so that nobody had to pause to remember the script while they were screaming in mortal terror about the tiger with its jaws around their sibling's skull. Anyway, Hank isn't home; he's trying to stop a team of government-sponsored hunters who - get this conservative reactionary bullshit - think that it's extremely, world-historically foolish to let 150 big cats roam around your house, and someone might get hurt. Pshaw. He is accompanied in this by his Maasai sidekick Mativo (Kyalo Mativo), whose entire character arc consists of variations on "fuck this white people nonsense". This was at the actor's direct request, and for his extreme good sense, he was the sole member of the cast to receive no wounds from any of the animals.

Anyway, Madelaine and the kids arrive at Hank's villa, and are staggered to find it is overrun with lions. For the rest of the movie, they endeavor not to die, and it's a little bit confusing how they manage to be successful. Eventually, Hank comes back, and the whole family is moved to cuddle and pet and sleep next to the animals who just spent a day and night terrorising them at the most fundamental animal level of fear that we hairless savannah apes are capable of feeling when confronted with the bone-shaking roar of a hunting lion. But it's cute and wacky! You can tell because the music is silly! Ignore Melanie and Jerry's lacerating, shrill shrieks, erupting from their body at a pre-verbal level that no actor could possible fake!

I mean, kudos. Ku-fucking-dos. Marshall and Hedren wanted to make a movie about how swell lions were, and they made that movie, no matter how often they had to wipe the blood from their face to see what they were doing (Marshall took so many hits from the cats that he had to be hospitalised for gangrene. Gangrene. From a movie shoot). It is a light, upbeat story about how sweet and good the big kitties are, and no amount of visceral tension as we watch, helpless to stop, as various humans are turned into rubber-limbed playthings by animals who are never malicious. I mean, you can tell. They're not hunting. They're not angry. But my cat wasn't hunting or angry when she woke me up this morning by biting my ear, and she's only about 16 inches long, and that hurt like hell. Cats are assholes - big cats are big assholes. And Roar does absolutely superb work in capturing the heft and power of its feline cast, genuinely and successfully arguing for their majesty and vitalism. It does so in the most fucked-up, tonally surreal, viscerally unsettling way possible, but hey, the goal was to make me fall in love with lions, and I guess I did. At any rate, even having seen it twice now, I'm still struck by the sheer grandiose madness of the whole thing, and not bored for a minute, no matter how dopey and trifling the plot is. It is one of the truly singular one-offs in all of cinema history - thank the dear Lord for that!