We choose to go to the Moon

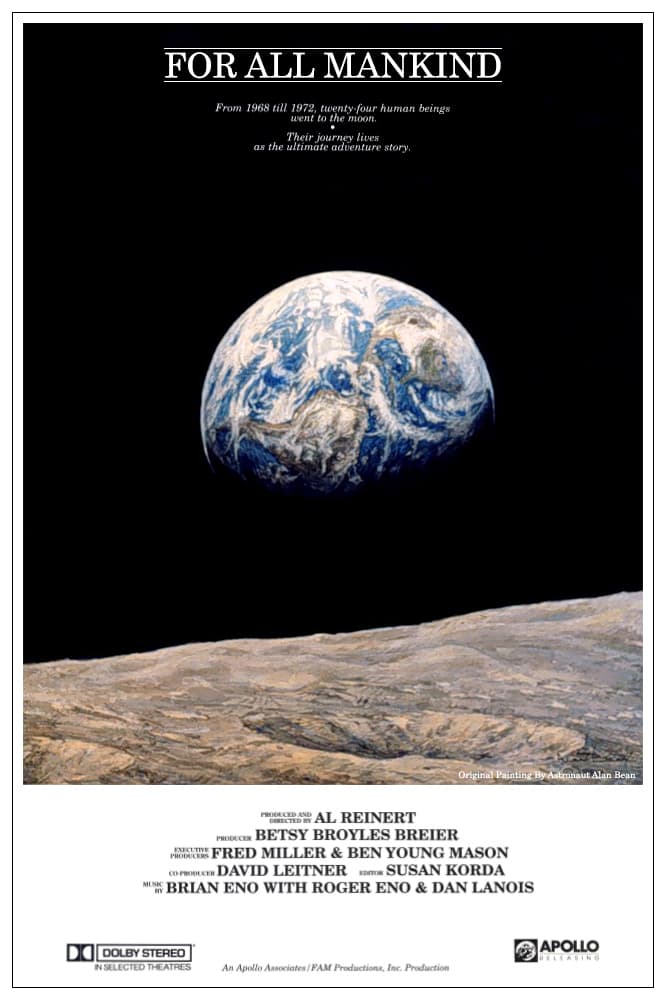

The opening of For All Mankind, the extraordinary 1989 found footage documentary assembled by director Al Reinert and editor Susan Korda, serves as something of a thesis statement for the rest of the film's 80 minutes. Over black, we hear two things: President John F. Kennedy declaiming passages from his wonderful 12 September 1962 speech in support of landing American men on the surface of Earth's moon and returning them home safely, and there is... I almost don't know what to call it. It's just bass, a deep rumble that bleeds into the sound of the crowd cheering Kennedy, but is heartier and more guttural and deeper, filling all the space in the theater with a blanket of sonic vibration (or the living room, or whatever place you watch this movie on the biggest screen available with the best available speakers - this film, as they say, should be played loud). And then the images show up: Kennedy's speech cross-cuts with footage of Apollo rockets launching as he describes the extraordinary technology, much of it not even invented, that will facilitate the moon landing. That sound, then, is maybe the engine of a rocket, or maybe it is a musical interpolation designed to make us feel the visceral power of those rockets, but either way, the actual fact of the sound isn't as important as what it does. Because what it does is a something down in the pit of your gut and all down your arms to your fingertips & your legs to your toes (seriously, this film should be played loud). And so we get two things contrasted: Kennedy's words are sensible, concrete, specific, material, pragmatic; he speaks in the post-WWII tones of doing things through Good Honest Science. Meanwhile, the rest of the soundtrack is pure emotional grandiosity; it is not even rhetorically inspiring in the way that Kennedy's most beautiful passages are, but more spiritual and transporting, awestruck not in the way we are at impressive feats of technology, but in the way we are impressed at the face of God.

That is the central tension that Reinert will mine, basically without pause, for the rest of the movie. For All Mankind consists primarily of three different things. One of these is a substantial collection of archival footage held by NASA from the ten Apollo missions between December 1968 and November 1972, and the archival audio accompanying it (the later documentaries In the Shadow of the Moon, from 2007, and Apollo 11, from 2019, would have even bigger archives to play with, and Reinert and Korda borrowed footage from the Gemini program as well, but you never think about these things while the movie is playing). Another is a series of interviews Reinert conducted starting in 1976, with 13 of the Apollo program astronauts. The third is a score composed by ambient music superstar Brian Eno in 1983 for the first version of this project, a different assemblage of the footage, without the interviews, titled Apollo. The film has been assembled into a thing somewhat more like a synopsis rather than a nuts-and-bolts documentary: the launch, flight to the moon, landing, flight back, and re-entry are all summarised through the footage of several different flights, while we hear male voices, distinct but unidentified (the film famously doesn't provide any title cards identifying who is speaking; the Criterion Collection home video releases, at least, provide the option to turn on a subtitle track providing that information, but it seems wholly against the spirit of the thing to use that function), talking about their experience, less a collection of individuals than as a collective personality of The Apollo Astronaut.

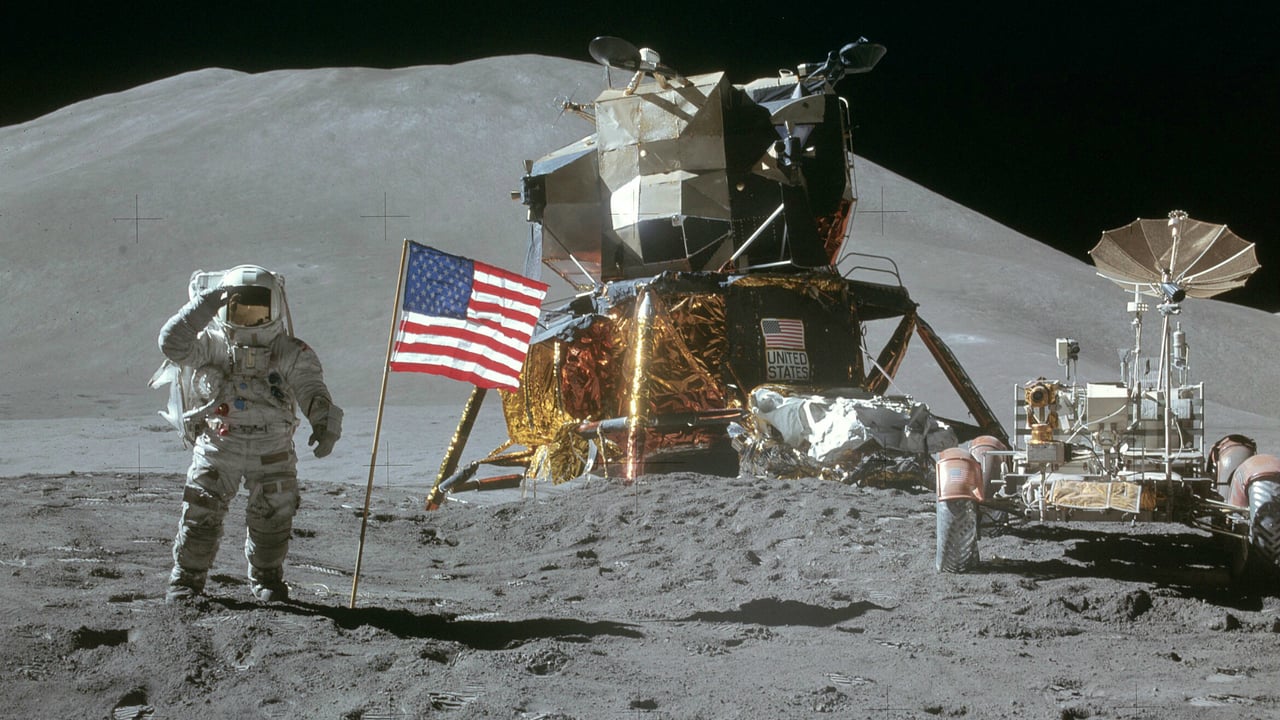

If you're counting, this summary was made up of three different forms of audio and only one form of video, which is the secret about For All Mankind that doesn't get nearly enough attention. The film was sold, and received, on the basis of its extraordinary images, many of which had never been seen before, and there's absolutely no doubt that those images are amazing. Those images, after all, were shot on the surface of the fucking Moon (the film ends with its solitary joke: a credit reading "Filmed on location by the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration")

But any dopey hack could slop together amazing footage and have it be amazing. The reason For All Mankind is a marvelous film, rather than just a marvelous slideshow, is its soundtrack. Those three elements - archival audio, interviews, Eno's music - circle around each other, shifting in prominence from point point, sometimes with one or two of three pieces dropping out partially or entirely, challenging each other and offering counterpoint. It's the Kennedy opening, over and over again, for a whole feature film. In the archival audio, we hear the blunt pragmatic stuff, spitting out data points, technical instructions, descriptions of math problems, and all the things that happen when you are responsible, in real time, for sending a fucking big metal tube into the sky on the back of an explosion and not murdering the three man strapped to it. It is not romantic about space flight because it can't be. The interviews are less blunt, but they're no less pragmatic - these men are not terribly invested in thinking of themselves as heroes or pioneers, just technicians doing a job and going about it with a bit of good humor to leaven the tension of it all. And we see that in the footage, too, which over-emphasises footage of the astronauts goofing off, singing, playing in zero-gravity. There is, in both, a sense of slightly confused amusement at the fact that these men all went to the surface of the fucking Moon, or at least flew in a lunar fucking orbit. But there is no weight. They eschew weight.

And that's where Eno comes in. For All Mankind would be a completely different movie without its music - it would, in fact, be fairly like In the Shadow of the Moon, which has the same unromantic pragmatism in its own interviews, conducted with many of the same men years later. And I admire the shit out of that movie, but it's certainly my least favorite of the "big three" Apollo documentaries, in part because it's so very sensibile. That is a word that's hard to apply to For All Mankind once the Eno music hits. The score is, to be hideously objective and intellectual about it, corny dated bullcrap. It comes from that place in the early 1980s where all dreamy electronica came, the same worldview of floating ethereal future-stuff that produced, say, Walt Disney World's EPCOT Center (the For All Mankind score, in fact, plays in certain parts of EPCOT as background music, and this could not possibly feel more appropriate). It is silly and terrifyingly earnest in its application of synthesizers, an odd thing to be earnest about. But let us say, just for the sake of it, that maybe we should not be hideously objective and intellectual, but instead that we should give ourselves over to the music and the movie, and if we do that - or, anyway, if I do that, and I'm the one writing this review - it transforms For All Mankind into something indelible and rapturous and otherworldly in the most profound possible way. When I think about space, I think about this soundtrack, and I somehow did so before I ever even heard the soundtrack; the first time I watched the film, my immediate, instinctive response to the music was, "yes, that's excactly it". The score floats, letting pure notes stretch and drift across one's ears, feeling untrammeled by weight or atmosphere or anything physical at all. It is one of the few genuinely awesome scores in cinema history, working not with bombast and grandeur, like the deafening Richard Strauss timpani that kicks off 2001: A Space Odyssey (and is referenced here), but with the ethereal - the "music of the spheres", if we want to go back that far.

So we have, on the one hand, lots of pragmatism and plainspokenness; we have on the other, images of sunrises over the lunar surface, images of the Earth rendered as a small slice of colored light in a black infinity, while Eno's music soars above and through them. "This was a job and we did it", say the astronauts. "But you are aware, are you not, that you went to the fucking Moon?" wails and sobs and laughs the musical score. It's an incredibly productive tension, one that makes For All Mankind a great document of one of the primary conflicts of Western history since the end of World War II: our sensible materialism and knowledge, our understanding of how the universe functions that has allowed us to great the most astonishing miracles, running aground on the deep need of humans, mandated by evolution, to find things worshipful and spiritual and grand - to find those miracles miraculous, basically. "We went to the moon", says the film, "and it was a major achievement of physics"; "yes, we went to the moon", the film agrees, "and it was a major achievement of the human spirit".

For All Mankind has its very definite shortcomings: it is, for one thing, a terrible way to learn anything about the Apollo program, with its complete allergy to even the most insubstantial amount of context. It's also prone to a heavy-handed literalism about which piece of footage to apply to which piece of audio, in a way that just underscores how much more work the soundtrack is doing than the imagery, no matter how mind-blowing the images are. But for holding such a perfect balance between its admiration for a scientific process and its almost mystical desire to romanticise and obfuscate the process, it's a masterpiece anyway. The film's subject isn't the Apollo program, it's what the Apollo program makes us feel, how we can find the transcendent in the resolutely physical. And that's, like, the whole project of modernism right there, baked into 80 wonderful minutes that don't seem even a tiny bit aware that they're doing any such thing.

That is the central tension that Reinert will mine, basically without pause, for the rest of the movie. For All Mankind consists primarily of three different things. One of these is a substantial collection of archival footage held by NASA from the ten Apollo missions between December 1968 and November 1972, and the archival audio accompanying it (the later documentaries In the Shadow of the Moon, from 2007, and Apollo 11, from 2019, would have even bigger archives to play with, and Reinert and Korda borrowed footage from the Gemini program as well, but you never think about these things while the movie is playing). Another is a series of interviews Reinert conducted starting in 1976, with 13 of the Apollo program astronauts. The third is a score composed by ambient music superstar Brian Eno in 1983 for the first version of this project, a different assemblage of the footage, without the interviews, titled Apollo. The film has been assembled into a thing somewhat more like a synopsis rather than a nuts-and-bolts documentary: the launch, flight to the moon, landing, flight back, and re-entry are all summarised through the footage of several different flights, while we hear male voices, distinct but unidentified (the film famously doesn't provide any title cards identifying who is speaking; the Criterion Collection home video releases, at least, provide the option to turn on a subtitle track providing that information, but it seems wholly against the spirit of the thing to use that function), talking about their experience, less a collection of individuals than as a collective personality of The Apollo Astronaut.

If you're counting, this summary was made up of three different forms of audio and only one form of video, which is the secret about For All Mankind that doesn't get nearly enough attention. The film was sold, and received, on the basis of its extraordinary images, many of which had never been seen before, and there's absolutely no doubt that those images are amazing. Those images, after all, were shot on the surface of the fucking Moon (the film ends with its solitary joke: a credit reading "Filmed on location by the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration")

But any dopey hack could slop together amazing footage and have it be amazing. The reason For All Mankind is a marvelous film, rather than just a marvelous slideshow, is its soundtrack. Those three elements - archival audio, interviews, Eno's music - circle around each other, shifting in prominence from point point, sometimes with one or two of three pieces dropping out partially or entirely, challenging each other and offering counterpoint. It's the Kennedy opening, over and over again, for a whole feature film. In the archival audio, we hear the blunt pragmatic stuff, spitting out data points, technical instructions, descriptions of math problems, and all the things that happen when you are responsible, in real time, for sending a fucking big metal tube into the sky on the back of an explosion and not murdering the three man strapped to it. It is not romantic about space flight because it can't be. The interviews are less blunt, but they're no less pragmatic - these men are not terribly invested in thinking of themselves as heroes or pioneers, just technicians doing a job and going about it with a bit of good humor to leaven the tension of it all. And we see that in the footage, too, which over-emphasises footage of the astronauts goofing off, singing, playing in zero-gravity. There is, in both, a sense of slightly confused amusement at the fact that these men all went to the surface of the fucking Moon, or at least flew in a lunar fucking orbit. But there is no weight. They eschew weight.

And that's where Eno comes in. For All Mankind would be a completely different movie without its music - it would, in fact, be fairly like In the Shadow of the Moon, which has the same unromantic pragmatism in its own interviews, conducted with many of the same men years later. And I admire the shit out of that movie, but it's certainly my least favorite of the "big three" Apollo documentaries, in part because it's so very sensibile. That is a word that's hard to apply to For All Mankind once the Eno music hits. The score is, to be hideously objective and intellectual about it, corny dated bullcrap. It comes from that place in the early 1980s where all dreamy electronica came, the same worldview of floating ethereal future-stuff that produced, say, Walt Disney World's EPCOT Center (the For All Mankind score, in fact, plays in certain parts of EPCOT as background music, and this could not possibly feel more appropriate). It is silly and terrifyingly earnest in its application of synthesizers, an odd thing to be earnest about. But let us say, just for the sake of it, that maybe we should not be hideously objective and intellectual, but instead that we should give ourselves over to the music and the movie, and if we do that - or, anyway, if I do that, and I'm the one writing this review - it transforms For All Mankind into something indelible and rapturous and otherworldly in the most profound possible way. When I think about space, I think about this soundtrack, and I somehow did so before I ever even heard the soundtrack; the first time I watched the film, my immediate, instinctive response to the music was, "yes, that's excactly it". The score floats, letting pure notes stretch and drift across one's ears, feeling untrammeled by weight or atmosphere or anything physical at all. It is one of the few genuinely awesome scores in cinema history, working not with bombast and grandeur, like the deafening Richard Strauss timpani that kicks off 2001: A Space Odyssey (and is referenced here), but with the ethereal - the "music of the spheres", if we want to go back that far.

So we have, on the one hand, lots of pragmatism and plainspokenness; we have on the other, images of sunrises over the lunar surface, images of the Earth rendered as a small slice of colored light in a black infinity, while Eno's music soars above and through them. "This was a job and we did it", say the astronauts. "But you are aware, are you not, that you went to the fucking Moon?" wails and sobs and laughs the musical score. It's an incredibly productive tension, one that makes For All Mankind a great document of one of the primary conflicts of Western history since the end of World War II: our sensible materialism and knowledge, our understanding of how the universe functions that has allowed us to great the most astonishing miracles, running aground on the deep need of humans, mandated by evolution, to find things worshipful and spiritual and grand - to find those miracles miraculous, basically. "We went to the moon", says the film, "and it was a major achievement of physics"; "yes, we went to the moon", the film agrees, "and it was a major achievement of the human spirit".

For All Mankind has its very definite shortcomings: it is, for one thing, a terrible way to learn anything about the Apollo program, with its complete allergy to even the most insubstantial amount of context. It's also prone to a heavy-handed literalism about which piece of footage to apply to which piece of audio, in a way that just underscores how much more work the soundtrack is doing than the imagery, no matter how mind-blowing the images are. But for holding such a perfect balance between its admiration for a scientific process and its almost mystical desire to romanticise and obfuscate the process, it's a masterpiece anyway. The film's subject isn't the Apollo program, it's what the Apollo program makes us feel, how we can find the transcendent in the resolutely physical. And that's, like, the whole project of modernism right there, baked into 80 wonderful minutes that don't seem even a tiny bit aware that they're doing any such thing.