Blockbuster History: Alligators

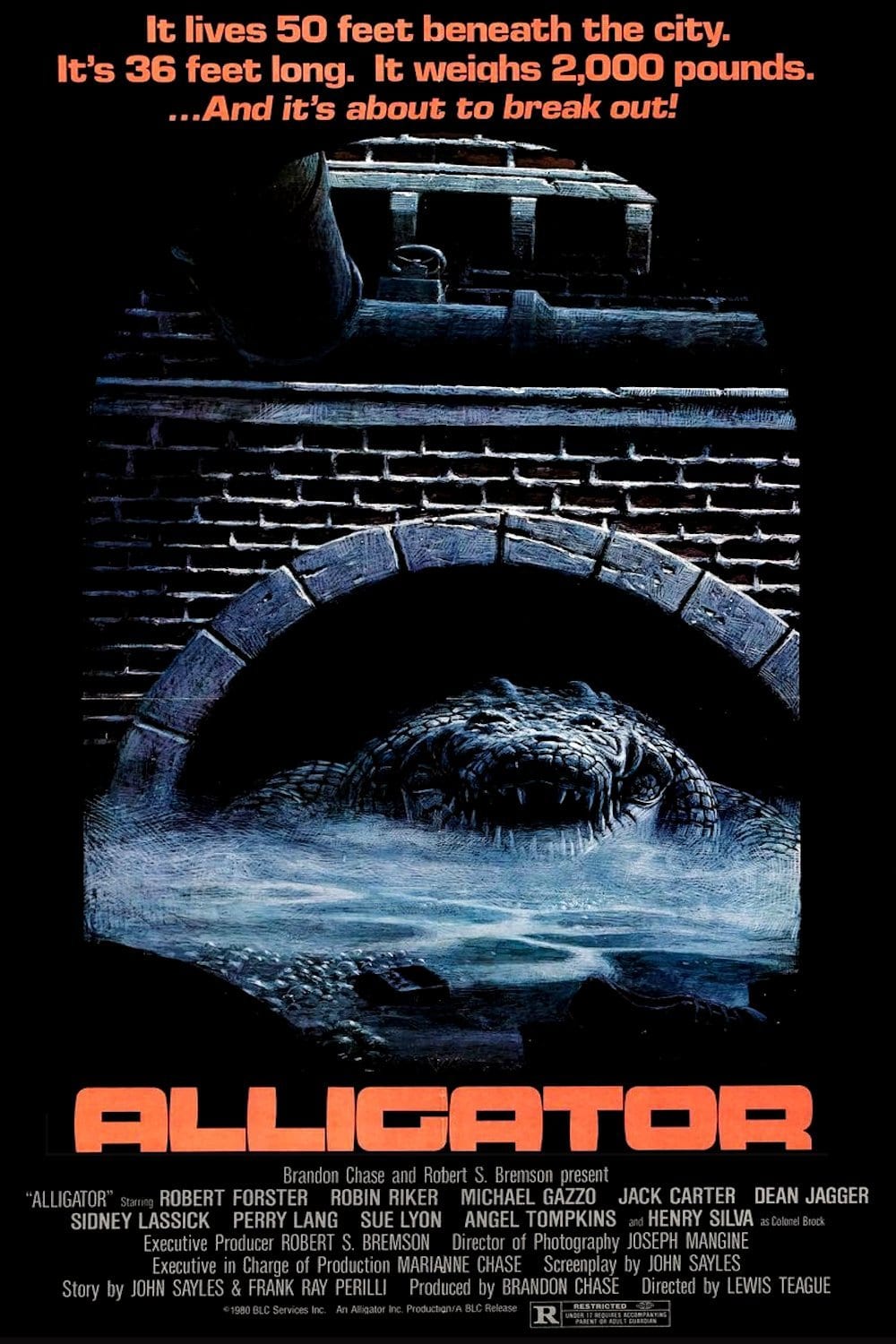

Intermittently this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Crawl, brings back to the big-screen the ancient rivalry between human and alligator. There have been more than a few movies on this topic, but only one with such a single-minded title.

The post-Jaws "monstrous killer animal" boom was very much a thing of the late-1970s, so the fact that Alligator didn't come out until 1980 feels like it should be a huge strike against it. In just about every other major genre fad I can name (e.g. the Exorcist mimics, the Mad Max 2 ripoffs, and of course, the slashers), the later we get in time, the more dismal exhaustion we encounter in individual titles, and the more bitter the profound lack of inspiration feels. When we have on our hands a genre responsible for such unwatchable dogs as 1977's Grizzly or Tentacles - a genre about which I can say, with no hint of irony and a completely straight face, that the demented Orca is one of its most entertaining highlights - the notion of arriving at one of "the late ones" is automatically a sign that we need to proceed with caution, almost as much as we'd need to around an actual 30-foot mutant alligator. And yet, Alligator is a snazzy little delight, far closer to the best of its breed than the worst, with some of the sharpest character work the genre has on offer to go with some unexpectedly clever visual tricks. It's, like, good, something that even the fun killer animal movies could rarely claim.

The thing that holds the film back, and is perhaps at least a small part of the reason the film doesn't have much in the way of visibility even among killer animal movie fans, is that the one film in the whole world you most want to compare it to is better than it in every single way. Alligator was written, first, by Frank Ray Perilli and then handed off to John Sayles (who had just made the leap into directing tender, quiet indie dramas the year prior, with Return of the Secaucus 7) for script-doctoring duties; Sayles junked virtually everything and wrote the movie fresh, which was unquestionably to its benefit as a finished work. It also made the film irresistibly similar to the Sayles-scripted Piranha from 1978, itself the best of all Jaws knock-offs by no little margin. I wouldn't go so far as to call Alligator a full-on retread of Piranha, but they share quite a bit, especially and most importantly a sly sense of humor rooted in character and the scenario. That particular, distinctive sense of humor is found in basically no other killer animal movie of any era that I can name, which makes pairing these two films almost unbearably easy. And Piranha is just, like, better. Maybe because it has a director already prone to sly humor in the form of Joe Dante, while Alligator makes do with Lewis Teague, whose unprepossessing career probably peaked, visibility-wise, with the draggy 1983 Stephen King adaptation Cujo, or perhaps the joyless grind of Romancing the Stone's glassy-eyed sequel The Jewel of the Nile, from 1985. Alligator blows both of those out of the water, though I'd still trade Teague in for Dante without a moment's hesitation. Still, let's accentuate the positive: Alligator is darn good, and better than I'd ever have excepted in a bunch of ways.

The film is based on one of the ripest of all North American urban legends: the pet alligator who gets flushed down the toilet, becoming a terrifying king of the sewer. In this case, the gator is purchased by young Marisa Kendall (Leslie Brown) during a family trip to Florida, during that fucking psychotic time in history when that kind of thing was legal. She's an inquisitive, curious sort, our Marisa, but she has the misfortune of a terribly shitty father who sends poor Ramón - the gator's name - into the sewers one day for little obvious reason other than being in a perpetually foul mood. Twelve years later, Marisa (now played by Robin Riker) has grown up to to become the Midwest's foremost herpetologist - where in the Midwest isn't clear; it acts like Chicago, but the only visual indication of a setting we get is a "Welcome to Missouri" sign, and the only statement of place is that it's not St. Louis. So imagine, if it doesn't break your brain, a hybrid of Kansas City and Chicago. Anyway, we'll catch up with Marisa later. For right now, we're finding out what happened to Ramón. Seems that a local pharmaceutical company has been testing out an artificial rapid-growth hormone, in the hopes of growing bigger, meatier livestock. Sadly, they have been carrying out this testing on kidnapped dogs, provided by corrupt pet store own Mr. Gutchel (Sydney Lassick), who also got stuck with the job of disposing of the animals' mangled carcasses. He does this by dumping them in the sewer, assuming that even if they get found, they'll be effectively untraceable. Which turns out to be true, but it also means that a certain baby alligator has been dining for years on dogs full of chemicals that make you enormous and give you an insatiable appetite.

The case of the dognapping spree as well as the dead, mutilated body of a sewer worker that was also Ramón's handiwork both independently end up on the desk of Detective David Madison (Robert Forster), which raises important questions about the division of labor in this particular police department. But let's not start sniping at the film now, because this is also exactly where it starts to become good. And not jut because "David Madison" is an all-time great fictional cop name. What makes Alligator more than just a junky giant monster movie is, in no small part, the oddly credible, colorfully-etched characters who make up its ensemble, and David is front and center in that company. It helps, of course, that Forster is quietly and unassumingly one of the great character actors of his generation; Alligator came out in the period where he was starting to move into leading roles in low-budget genre fare, and it's a perfect embodiment of how much such a production can be elevated by having the right leading man. Most movies of this sort make a big deal about having their heroes be thick hunks carved from granite; Alligator makes a running joke out of Forster's receding hairline and general grumpiness, presenting the loner cop (he has a reputation for getting his partner killed) as somebody who responds to the doubtful looks of his superiors and colleagues not with cool arrogance, but with peevish annoyance. You know, the way you or I or any real person would. He sighs, he grumbles, he looks around with an appearance of mildly amused exhaustion pretty much throughout: he is, and I say this with the gravest respect for Forster, a bit of a blue-collar schlub. How much of this is direct from Sayles (no stranger to blue collars, or schlubs) and how much is the result of casting Forster rather than a smoother but shallower matinee-idol type in the role, I can't say. But it's pretty much perfect either way, giving Alligator a kind of down-rent, self-amused credibility when it's still in its "cop investigating a mystery" mode, long before it starts to bring in the alligator action.

The alligator action, mind you, is excellent. Ramón is, like Bruce the shark in Jaws, played by a huge animatronic that kept breaking, and while Teague is absolutely no Steven Spielberg, he managed in much the same way to make a virtue out of necessity. In a lot of places, the alligator is kept as an impression more than a visible threat. This is especially true when we follow this character or that into the sewers: the hunt by David and his doomed partner Kelly (Perry Lang) is an especially inspired moment, relying on noise that could be just about anything, in a film that didn't have this title, and small indications of movement. In one thoroughly lovely scene, the cops' wiggle their flashlights around without looking and inadvertently shine a beam right on the alligator's face, without either of them seeing that it's there: it's a beautifully-staged jump scare that's as much darkly comic as it is shocking. Teague is generally great at thus relying on the gloom and irregular lines of the sewer to help hide his gator and provide unsettling atmosphere; the film suffers a bit after the animal is revealed to the world and starts spending more time outside, but by that point, the film has built up enough goodwill to survive it. Also, the film shifts genres from horror-thriller to sardonic police procedural (without completely shedding its thriller elements), so mood becomes a touch less prominent, as the writing and acting come to the fore.

And frankly, the mere fact that I could write that last sentence about a movie with a 36-foot alligator as its title character without my face melting speaks to how smart Alligator is about playing in its genre sandbox. The film nails the same impeccable balance that Piranha did: it's funny and self-aware about the ridiculous contrivances of its genre, and it's also straight-faced in treating the threat of that impossible crocodilian as a real problem to solve, and it never mixes these two tones in a way that makes it feels like it's belittling its own content. Basically, the film understands that giant monster movies are fun, and part of the fun comes from taking them at least a little bit seriously. Seriously enough that we root for our heroes - and for the gator, as long as it's attacking the bad people. But at the same time, it doesn't mind letting all of the characters, including the love interest (that being Marisa, as it turns out), make fun of the hero's balding head.

The result is both an exemplary genre film and a snappy, loving parody of the same. Sometimes, it's both at once: one never quite knows whether Marisa's effortless competence, scientific curiosity, and eager attitude, all startling qualities in a woman in a monster movie, is Sayles's way of satirising the genre's tropes, or merely his way of making a more robust, fleshed-out, humane version of the genre. Same with the astonishing! coincidences! that run throughout the plot without ever actually mattering: nobody other than audience ever learns the full details of what happens with the dognapping plot, or that Marisa's own past is coming back in the form of the ravenous gator now - she never even meets the monster (and, it occurs to me, it's only the irresistible implication of editing, nothing ever presented directly, that even leads me to assume that Ramón is the same creature terrorising the city).

Whatever the case, the point is the same: Alligator is a movie that loves it genre and still realises how fucking stupid the genre is, attacking it with the playful irony of a dear friend or lover rather than the smugness of a critic. And on top of its wit and its violence, it finds room to present an engaging, if not exactly garden-fresh, human story about a good, beleaguered cop doing what he can in an impossible situation. Aye, I'd be able to repeat most of the words in this review if I was talking about Piranha, and there'd be more giddy enthusiasm behind them; but not-quite-as-good as the second-best killer animal film ever made still leaves a hell of a lot room for Alligator to be a great deal of winking fun in its own right: smartly-written, sensitively acted, and boasting a monster who gets just the right amount of the right kind of screen time to make a huge impression.

The post-Jaws "monstrous killer animal" boom was very much a thing of the late-1970s, so the fact that Alligator didn't come out until 1980 feels like it should be a huge strike against it. In just about every other major genre fad I can name (e.g. the Exorcist mimics, the Mad Max 2 ripoffs, and of course, the slashers), the later we get in time, the more dismal exhaustion we encounter in individual titles, and the more bitter the profound lack of inspiration feels. When we have on our hands a genre responsible for such unwatchable dogs as 1977's Grizzly or Tentacles - a genre about which I can say, with no hint of irony and a completely straight face, that the demented Orca is one of its most entertaining highlights - the notion of arriving at one of "the late ones" is automatically a sign that we need to proceed with caution, almost as much as we'd need to around an actual 30-foot mutant alligator. And yet, Alligator is a snazzy little delight, far closer to the best of its breed than the worst, with some of the sharpest character work the genre has on offer to go with some unexpectedly clever visual tricks. It's, like, good, something that even the fun killer animal movies could rarely claim.

The thing that holds the film back, and is perhaps at least a small part of the reason the film doesn't have much in the way of visibility even among killer animal movie fans, is that the one film in the whole world you most want to compare it to is better than it in every single way. Alligator was written, first, by Frank Ray Perilli and then handed off to John Sayles (who had just made the leap into directing tender, quiet indie dramas the year prior, with Return of the Secaucus 7) for script-doctoring duties; Sayles junked virtually everything and wrote the movie fresh, which was unquestionably to its benefit as a finished work. It also made the film irresistibly similar to the Sayles-scripted Piranha from 1978, itself the best of all Jaws knock-offs by no little margin. I wouldn't go so far as to call Alligator a full-on retread of Piranha, but they share quite a bit, especially and most importantly a sly sense of humor rooted in character and the scenario. That particular, distinctive sense of humor is found in basically no other killer animal movie of any era that I can name, which makes pairing these two films almost unbearably easy. And Piranha is just, like, better. Maybe because it has a director already prone to sly humor in the form of Joe Dante, while Alligator makes do with Lewis Teague, whose unprepossessing career probably peaked, visibility-wise, with the draggy 1983 Stephen King adaptation Cujo, or perhaps the joyless grind of Romancing the Stone's glassy-eyed sequel The Jewel of the Nile, from 1985. Alligator blows both of those out of the water, though I'd still trade Teague in for Dante without a moment's hesitation. Still, let's accentuate the positive: Alligator is darn good, and better than I'd ever have excepted in a bunch of ways.

The film is based on one of the ripest of all North American urban legends: the pet alligator who gets flushed down the toilet, becoming a terrifying king of the sewer. In this case, the gator is purchased by young Marisa Kendall (Leslie Brown) during a family trip to Florida, during that fucking psychotic time in history when that kind of thing was legal. She's an inquisitive, curious sort, our Marisa, but she has the misfortune of a terribly shitty father who sends poor Ramón - the gator's name - into the sewers one day for little obvious reason other than being in a perpetually foul mood. Twelve years later, Marisa (now played by Robin Riker) has grown up to to become the Midwest's foremost herpetologist - where in the Midwest isn't clear; it acts like Chicago, but the only visual indication of a setting we get is a "Welcome to Missouri" sign, and the only statement of place is that it's not St. Louis. So imagine, if it doesn't break your brain, a hybrid of Kansas City and Chicago. Anyway, we'll catch up with Marisa later. For right now, we're finding out what happened to Ramón. Seems that a local pharmaceutical company has been testing out an artificial rapid-growth hormone, in the hopes of growing bigger, meatier livestock. Sadly, they have been carrying out this testing on kidnapped dogs, provided by corrupt pet store own Mr. Gutchel (Sydney Lassick), who also got stuck with the job of disposing of the animals' mangled carcasses. He does this by dumping them in the sewer, assuming that even if they get found, they'll be effectively untraceable. Which turns out to be true, but it also means that a certain baby alligator has been dining for years on dogs full of chemicals that make you enormous and give you an insatiable appetite.

The case of the dognapping spree as well as the dead, mutilated body of a sewer worker that was also Ramón's handiwork both independently end up on the desk of Detective David Madison (Robert Forster), which raises important questions about the division of labor in this particular police department. But let's not start sniping at the film now, because this is also exactly where it starts to become good. And not jut because "David Madison" is an all-time great fictional cop name. What makes Alligator more than just a junky giant monster movie is, in no small part, the oddly credible, colorfully-etched characters who make up its ensemble, and David is front and center in that company. It helps, of course, that Forster is quietly and unassumingly one of the great character actors of his generation; Alligator came out in the period where he was starting to move into leading roles in low-budget genre fare, and it's a perfect embodiment of how much such a production can be elevated by having the right leading man. Most movies of this sort make a big deal about having their heroes be thick hunks carved from granite; Alligator makes a running joke out of Forster's receding hairline and general grumpiness, presenting the loner cop (he has a reputation for getting his partner killed) as somebody who responds to the doubtful looks of his superiors and colleagues not with cool arrogance, but with peevish annoyance. You know, the way you or I or any real person would. He sighs, he grumbles, he looks around with an appearance of mildly amused exhaustion pretty much throughout: he is, and I say this with the gravest respect for Forster, a bit of a blue-collar schlub. How much of this is direct from Sayles (no stranger to blue collars, or schlubs) and how much is the result of casting Forster rather than a smoother but shallower matinee-idol type in the role, I can't say. But it's pretty much perfect either way, giving Alligator a kind of down-rent, self-amused credibility when it's still in its "cop investigating a mystery" mode, long before it starts to bring in the alligator action.

The alligator action, mind you, is excellent. Ramón is, like Bruce the shark in Jaws, played by a huge animatronic that kept breaking, and while Teague is absolutely no Steven Spielberg, he managed in much the same way to make a virtue out of necessity. In a lot of places, the alligator is kept as an impression more than a visible threat. This is especially true when we follow this character or that into the sewers: the hunt by David and his doomed partner Kelly (Perry Lang) is an especially inspired moment, relying on noise that could be just about anything, in a film that didn't have this title, and small indications of movement. In one thoroughly lovely scene, the cops' wiggle their flashlights around without looking and inadvertently shine a beam right on the alligator's face, without either of them seeing that it's there: it's a beautifully-staged jump scare that's as much darkly comic as it is shocking. Teague is generally great at thus relying on the gloom and irregular lines of the sewer to help hide his gator and provide unsettling atmosphere; the film suffers a bit after the animal is revealed to the world and starts spending more time outside, but by that point, the film has built up enough goodwill to survive it. Also, the film shifts genres from horror-thriller to sardonic police procedural (without completely shedding its thriller elements), so mood becomes a touch less prominent, as the writing and acting come to the fore.

And frankly, the mere fact that I could write that last sentence about a movie with a 36-foot alligator as its title character without my face melting speaks to how smart Alligator is about playing in its genre sandbox. The film nails the same impeccable balance that Piranha did: it's funny and self-aware about the ridiculous contrivances of its genre, and it's also straight-faced in treating the threat of that impossible crocodilian as a real problem to solve, and it never mixes these two tones in a way that makes it feels like it's belittling its own content. Basically, the film understands that giant monster movies are fun, and part of the fun comes from taking them at least a little bit seriously. Seriously enough that we root for our heroes - and for the gator, as long as it's attacking the bad people. But at the same time, it doesn't mind letting all of the characters, including the love interest (that being Marisa, as it turns out), make fun of the hero's balding head.

The result is both an exemplary genre film and a snappy, loving parody of the same. Sometimes, it's both at once: one never quite knows whether Marisa's effortless competence, scientific curiosity, and eager attitude, all startling qualities in a woman in a monster movie, is Sayles's way of satirising the genre's tropes, or merely his way of making a more robust, fleshed-out, humane version of the genre. Same with the astonishing! coincidences! that run throughout the plot without ever actually mattering: nobody other than audience ever learns the full details of what happens with the dognapping plot, or that Marisa's own past is coming back in the form of the ravenous gator now - she never even meets the monster (and, it occurs to me, it's only the irresistible implication of editing, nothing ever presented directly, that even leads me to assume that Ramón is the same creature terrorising the city).

Whatever the case, the point is the same: Alligator is a movie that loves it genre and still realises how fucking stupid the genre is, attacking it with the playful irony of a dear friend or lover rather than the smugness of a critic. And on top of its wit and its violence, it finds room to present an engaging, if not exactly garden-fresh, human story about a good, beleaguered cop doing what he can in an impossible situation. Aye, I'd be able to repeat most of the words in this review if I was talking about Piranha, and there'd be more giddy enthusiasm behind them; but not-quite-as-good as the second-best killer animal film ever made still leaves a hell of a lot room for Alligator to be a great deal of winking fun in its own right: smartly-written, sensitively acted, and boasting a monster who gets just the right amount of the right kind of screen time to make a huge impression.