Save the dates

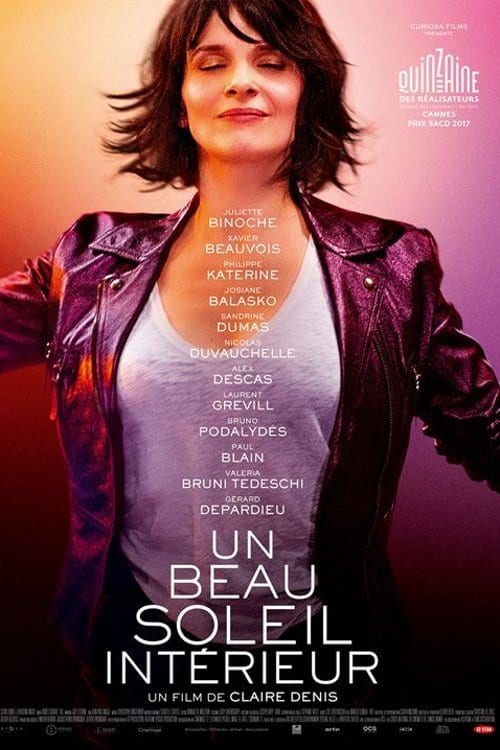

There are only two problems with Let the Sunshine In, and really neither one of them counts. The first is the slow and steady degradation of the title, which translates from the original French as A Beautiful Sun Inside; the first stop was to the somewhat corny and certainly less resonant Let the Sun Shine In, and the second was to remove that surprisingly crucial space between "Sun" and "Shine". The other is that this is a film that could have been made by any gifted filmmaker (especially a woman) with a sensitivity for small character beats who could translate things as little as sidelong glances into a strong sympathy for the joyless agony of being a single, middle-aged woman trying to date. And to be sure, we don't have all that many truly gifted filmmakers of this sort, but I think most of them would probably have made Let the Sunshine In look more or less exactly the way it looks here.

The thing is, this wasn't directed by a gifted filmmaker, it was directed by one of the greatest of all living filmmakers, Claire Denis, and it's just not quite enough. Denis's best work, which includes some of the best films made in the French language in the last thirty years, has a profound difficult streak. She doesn't just present characters, she digs into them, and interrogates them, challenges their self-narratives, demonstrates her love and respect for them by never giving them an easy way out when it's not earned. And she challenges the audience, asking so much of our attention and insight, presenting implications that we need to tease out, giving us fragments and then demonstrating her love and respect for us by knowing that we'll be able to find the humanity she wanted us to find. Let the Sunshine In is, comparatively, "nice". It's subtle, it's insightful, it presents a version of human experience very rarely shown in movies, but it basically tells us what's going to happen and then walks us through, not exactly holding our hand, but never letting us get more than a few feet away. Eight years (and somehow only two films) earlier, Denis made White Material, a film I admire tremendously, as her sole collaboration with Isabelle Huppert, and I think that works fairly well as a comparison: top-notch Denis is like Huppert, brimming with harshness that looks almost like hostility, and immoderately opaque; Let the Sunshine In is like Binoche, wise and artful and subtle, but basically friendly and easy to parse.

All of this being said, like I said, it doesn't actually count. If it wasn't a minor work by one of the giants of world cinema, it wouldn't be hard at all to appreciate Let the Sunshine In as a very sensitive and warm-hearted portrait of a woman who is on very much the wrong track, but only because life has close off all other possibilities. There's very little in the way of a plot: some time after divorcing her husband, for unstated reasons that are strongly suggested to have been fairly minor (they remain close and affectionate), Isabelle (Binoche) is tired of being alone. Unfortunately, the dating scene in Paris is pretty extravagantly crappy, and every man near her own age is pretty dismal in some or many ways. We watch all of these ways get demonstrated over the course of several awful dates, as Isabelle finds some way to convince herself that all of this is okay and even desirable, despite the evidence.

This leads to a distinctly narrow character study: we don't ever get a terribly strong sense of what happens to Isabelle when she's not miserably single. But that feels right, somehow: the script by Denis and Christine Angot is diagnosing one particular aspect of human experience, as examined from multiple angles and through a series of variables. Tying all of this together is an excellent central performance that finds Binoche in an unusually light register; while Isabelle is frustrated and lonely, she's not suffering, and the removal of the extreme states that tend to accrue to this actor free her up to do some more gentle, delicate work than she often gets to.

The film benefits substantially from this delicacy. Denis and her ever-reliable cinematographer Agnès Godard are playing a high-wire act, banking absolutely everything on medium shots of Binoche. It's a very calm, observant aesthetic, removing itself just far enough from Isabelle that we feel like we're watching her rather than watching with her, but staying close enough that we never lose sight of her emotional grind as the main focus of the movie. It also provides just exactly the right room for Binoche to use her entire body and not just her face to react and telegraph various emotions, some of them more amused than peeved, but all of them tinged with a degree of resignation. By no means is it one of her showiest performances, but it's maybe among the most finely-tuned: every time she widens her eyes, every time she visibly chokes back a laugh, and the way she positions herself relative to all of the different men in the film are perfectly calculated and do great work in defining Isabelle's mental state at all points.

The film makes the most out of Binoche's raw material by using it, in general, just as precisely. It's a straightforward movie, in terms of its blocking - a lot of conversations between two unmoving people - but within that very basic set-up, the use of camera angles and the timing of shots are excellent. Frequently, editor Guy Lecorne will break some little (or big) rule, cutting scenes in ways that feel a bit uncomfortable and unclear, and even this is precise: it feeds into the omnipresent discomfort Isabelle feels.

All told, it's beautifully crafted. I wish it didn't spend so much time on Isabelle's relationship with a young man, a nameless actor (Nicolas Duvauchelle). It imbalances things and puts him too much in the center of a story that desperately wants all of the male characters to drift in and out aimlessly. I also wish it was a little bit more robust; the unconventional treatment of the end credits (which made me gasp in shock, I am happy to say) does a lot to suggest that the film finds Isabelle's behavior self-negating and unhealthily desperate, which does get us into proper Denis territory a bit. But the film leading up to that moment doesn't necessarily set it up as clearly or as strongly as one might want. It's too cool and even-keeled for that. That being said even minor work from a great filmmaker (and this is probably Denis's most minor film since the 1990s) is a treat, and Binoche's performance is alone sufficient to make Let the Sunshine In an appealing character snapshot, even if it has a bit of a hard time consistently remaining at the level of a character study.

The thing is, this wasn't directed by a gifted filmmaker, it was directed by one of the greatest of all living filmmakers, Claire Denis, and it's just not quite enough. Denis's best work, which includes some of the best films made in the French language in the last thirty years, has a profound difficult streak. She doesn't just present characters, she digs into them, and interrogates them, challenges their self-narratives, demonstrates her love and respect for them by never giving them an easy way out when it's not earned. And she challenges the audience, asking so much of our attention and insight, presenting implications that we need to tease out, giving us fragments and then demonstrating her love and respect for us by knowing that we'll be able to find the humanity she wanted us to find. Let the Sunshine In is, comparatively, "nice". It's subtle, it's insightful, it presents a version of human experience very rarely shown in movies, but it basically tells us what's going to happen and then walks us through, not exactly holding our hand, but never letting us get more than a few feet away. Eight years (and somehow only two films) earlier, Denis made White Material, a film I admire tremendously, as her sole collaboration with Isabelle Huppert, and I think that works fairly well as a comparison: top-notch Denis is like Huppert, brimming with harshness that looks almost like hostility, and immoderately opaque; Let the Sunshine In is like Binoche, wise and artful and subtle, but basically friendly and easy to parse.

All of this being said, like I said, it doesn't actually count. If it wasn't a minor work by one of the giants of world cinema, it wouldn't be hard at all to appreciate Let the Sunshine In as a very sensitive and warm-hearted portrait of a woman who is on very much the wrong track, but only because life has close off all other possibilities. There's very little in the way of a plot: some time after divorcing her husband, for unstated reasons that are strongly suggested to have been fairly minor (they remain close and affectionate), Isabelle (Binoche) is tired of being alone. Unfortunately, the dating scene in Paris is pretty extravagantly crappy, and every man near her own age is pretty dismal in some or many ways. We watch all of these ways get demonstrated over the course of several awful dates, as Isabelle finds some way to convince herself that all of this is okay and even desirable, despite the evidence.

This leads to a distinctly narrow character study: we don't ever get a terribly strong sense of what happens to Isabelle when she's not miserably single. But that feels right, somehow: the script by Denis and Christine Angot is diagnosing one particular aspect of human experience, as examined from multiple angles and through a series of variables. Tying all of this together is an excellent central performance that finds Binoche in an unusually light register; while Isabelle is frustrated and lonely, she's not suffering, and the removal of the extreme states that tend to accrue to this actor free her up to do some more gentle, delicate work than she often gets to.

The film benefits substantially from this delicacy. Denis and her ever-reliable cinematographer Agnès Godard are playing a high-wire act, banking absolutely everything on medium shots of Binoche. It's a very calm, observant aesthetic, removing itself just far enough from Isabelle that we feel like we're watching her rather than watching with her, but staying close enough that we never lose sight of her emotional grind as the main focus of the movie. It also provides just exactly the right room for Binoche to use her entire body and not just her face to react and telegraph various emotions, some of them more amused than peeved, but all of them tinged with a degree of resignation. By no means is it one of her showiest performances, but it's maybe among the most finely-tuned: every time she widens her eyes, every time she visibly chokes back a laugh, and the way she positions herself relative to all of the different men in the film are perfectly calculated and do great work in defining Isabelle's mental state at all points.

The film makes the most out of Binoche's raw material by using it, in general, just as precisely. It's a straightforward movie, in terms of its blocking - a lot of conversations between two unmoving people - but within that very basic set-up, the use of camera angles and the timing of shots are excellent. Frequently, editor Guy Lecorne will break some little (or big) rule, cutting scenes in ways that feel a bit uncomfortable and unclear, and even this is precise: it feeds into the omnipresent discomfort Isabelle feels.

All told, it's beautifully crafted. I wish it didn't spend so much time on Isabelle's relationship with a young man, a nameless actor (Nicolas Duvauchelle). It imbalances things and puts him too much in the center of a story that desperately wants all of the male characters to drift in and out aimlessly. I also wish it was a little bit more robust; the unconventional treatment of the end credits (which made me gasp in shock, I am happy to say) does a lot to suggest that the film finds Isabelle's behavior self-negating and unhealthily desperate, which does get us into proper Denis territory a bit. But the film leading up to that moment doesn't necessarily set it up as clearly or as strongly as one might want. It's too cool and even-keeled for that. That being said even minor work from a great filmmaker (and this is probably Denis's most minor film since the 1990s) is a treat, and Binoche's performance is alone sufficient to make Let the Sunshine In an appealing character snapshot, even if it has a bit of a hard time consistently remaining at the level of a character study.

Categories: french cinema, love stories, romcoms