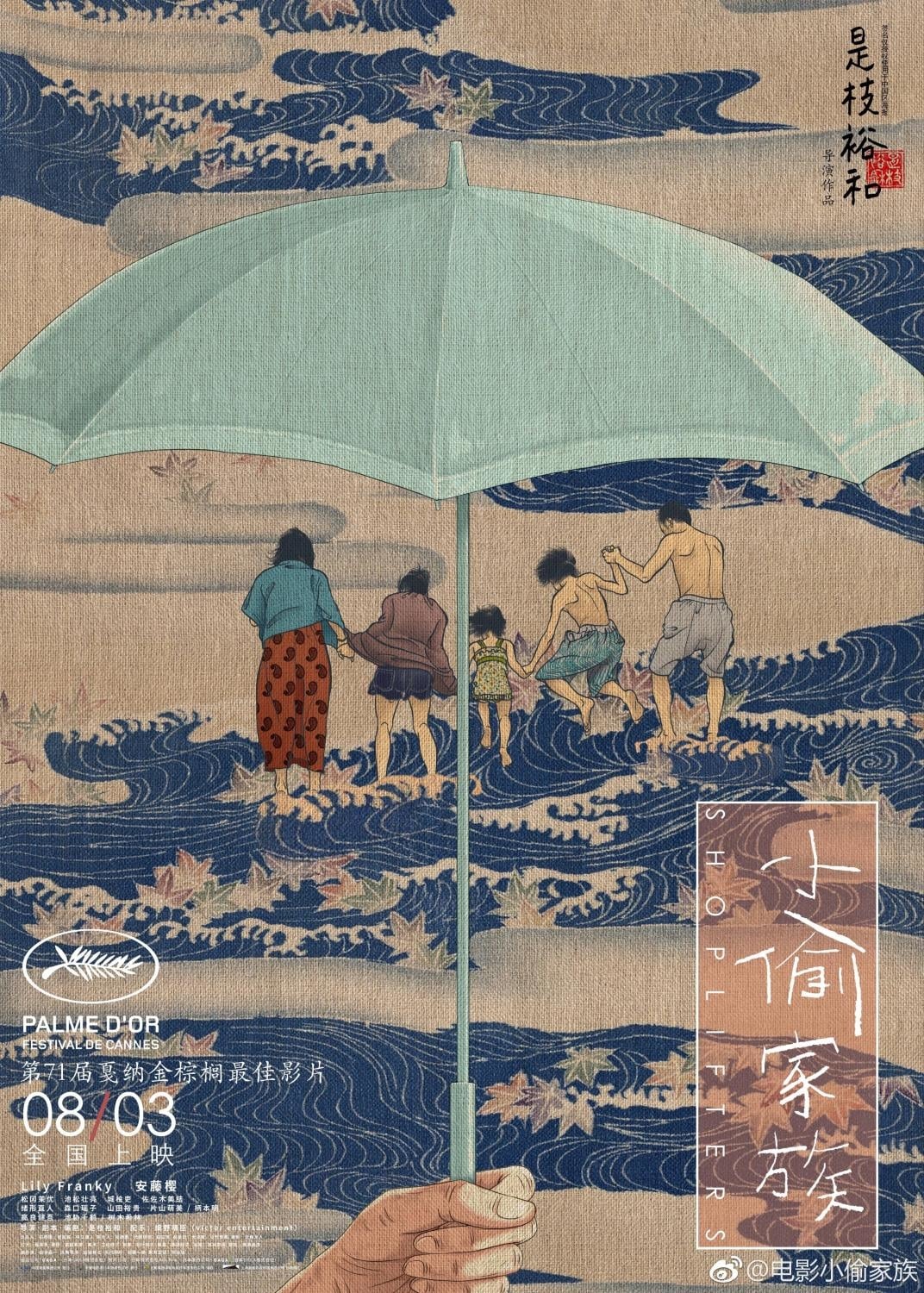

Crime family

There is nothing quite like the profound satisfaction of a quiet movie made with absolute confidence and no need to prove itself. And in this vein we have Shoplifters, the thirteenth narrative feature directed by Kore-eda Hirokazu (and a lucky #13 at that; it won the Palme d'Or at Cannes, the most wholly deserving film to take that prize in a few years). He's a filmmaker noted for the gentle, humane subtlety of his movies, and even so this feels like a particularly refined and rarefied bit of storytelling, in which the slightest flickers of facial expression and characters' reluctance to fill silences are as important in understanding their lives as anything that happens in the plot. Which, for the first 90 minutes, is very little anyway. It is a film of being: sitting in a space and spending time with people and sharing the love of families that form by choice and design rather than strictly by biology. And then it suddenly isn't, and that rupture is deeply upsetting, a nifty exercise in story structure reflecting the story's content to amplify the viewer's emotional response, as we are guided invisibly and inevitably by a master filmmaker.

But let's stick with those first 90 minutes a bit. Shoplifters manages to be both a wholly literal and an evocatively metaphorical title at one and the same time (the English title is, for once, better than the Japanese original, which literally translates as "Shoplifting Family"). The Shibatas are, in fact, shoplifters, as we learn in the opening scene when dad Osamu (Lily Franky) provides lookout for tween son Shota (Kairi Jo) as the boy grabs food. They do this in part out of need: the household of five lives in fairly extreme poverty, mostly getting by on the pension that elderly matriarch Hatsue (Kiki Kirin) still receives, courtesy of her late husband. Osamu has been injured and is unemployable; his wife Nobuyo (Ando Sakura) works for a laundry company; twentysomething Aki (Matsuoka Mayu) does stripteases at a hostess club. Shoplifting is just about the only thing keeping them in food, which is probably why they all seem so casual about asking a boy to do it.

And, in turn, it leads to the metaphor. Osamu finds a neighborhood girl of about four or five, Yuri (Sasaki Miyu), out in the snow one night, and brings her back home for dinner. After he and Nobuyo start to piece together enough clues to make it clear that the child is being abused (and overhearing her parents screaming about how much they dislike her, on top of it), they decide that there's no good reason not to keep her as their own, it making more sense for people who are caring and good to have children than people who are vicious. Once the police get involved, they change Yuri's haircut and name, and start to think about drawing her into the family business.

This all makes Shoplifters sound much more dramatic and fraught than is even a little bit the case. All of the above plot is expressed with little more than a contented sigh; the parents make their choice so smoothly and without having to belabor things with words, it almost doesn't register as a significant plot point. It's just something that happens. That's really what Shoplifters is: just things happening, and the Shibatas relying on the support they get from each other to cope with those things.

Tributes to the strength of family ties are nothing new, of course. What sets Shoplifters out is not at any points its originality, but the simple excellence of its execution. This is an extremely well-made film, particularly in its deceptively simple use of the camera to absorb as much of the Shibata home as possible. Kore-eda is especially concerned with creatingh a dense mise en scène that presents this household as a cluttered and welcoming space, in which nobody has enough room or anything like privacy. It's warm even as it feels heavy with the possibility of future conflict. In part, this is because we know we're watching a movie, and some shoe is going to have to drop. But it's also simply because we know that people can't actually live like this, and the comfort and happiness and family affection on display are laced through with minimalistically-expressed annoyance and resentment. The film boasts a truly great cast, one of the best I've seen all year: they're operating almost entirely at the level of who steals a glance at whom, what triggers a quick, toothy smile, and other quiet, casual beats. When the film demands more, they rise to the occasion effortlessly, as when Kiki has to play Hatsue play-acting as a nice old lady, or when Matsuoka deals with the film's strangest and possibly most beautiful and best scene, as Aki cradles the head of one of her clients, trying to encourage him in conversation, and falling instead into a reverie of her own.

The film is tremendously pleasurable simply as an opportunity to watch, in impeccably formed long (but not too long) takes, the behavior of a curiously functional dysfunctional family, not at all unlike the same director's 2004 Nobody Knows. And then the shift happens, and it's one punch to the gut until the movie ends. I am not sure that this is all honest; Kore-eda almost seems to be daring us to accept the revelations we receive, which feel both inevitable and arbitrary, and smack of misery porn without actually quite getting there. For one, nobody actually seems all that miserable, just aware that things have gone wrong in the exact way that they would do, if they were to go wrong. For another, the director suddenly shifts the rhythm of the film, which suddenly feels like we're spiraling of a cliff after having been sitting very still for hours. The movie starts to race through things that we can't stop or slow down any more than the characters do, and it only stops to allow us to absorb the full impact of its final couple of scenes, which matter-of-factly remind us that right and wrong can be very tricky to pin down and not what they sound like on paper, and the world is a lousy place that can be made just a little bit better by surrounding yourself with the kind of people who'll support you. It's impossibly heartbreaking, maybe just a bit too manipulative; but maybe also exactly manipulative enough. It is, at any rate, a film I eagerly look forward to visiting again sometime, just as soon as my soul can stand it.

But let's stick with those first 90 minutes a bit. Shoplifters manages to be both a wholly literal and an evocatively metaphorical title at one and the same time (the English title is, for once, better than the Japanese original, which literally translates as "Shoplifting Family"). The Shibatas are, in fact, shoplifters, as we learn in the opening scene when dad Osamu (Lily Franky) provides lookout for tween son Shota (Kairi Jo) as the boy grabs food. They do this in part out of need: the household of five lives in fairly extreme poverty, mostly getting by on the pension that elderly matriarch Hatsue (Kiki Kirin) still receives, courtesy of her late husband. Osamu has been injured and is unemployable; his wife Nobuyo (Ando Sakura) works for a laundry company; twentysomething Aki (Matsuoka Mayu) does stripteases at a hostess club. Shoplifting is just about the only thing keeping them in food, which is probably why they all seem so casual about asking a boy to do it.

And, in turn, it leads to the metaphor. Osamu finds a neighborhood girl of about four or five, Yuri (Sasaki Miyu), out in the snow one night, and brings her back home for dinner. After he and Nobuyo start to piece together enough clues to make it clear that the child is being abused (and overhearing her parents screaming about how much they dislike her, on top of it), they decide that there's no good reason not to keep her as their own, it making more sense for people who are caring and good to have children than people who are vicious. Once the police get involved, they change Yuri's haircut and name, and start to think about drawing her into the family business.

This all makes Shoplifters sound much more dramatic and fraught than is even a little bit the case. All of the above plot is expressed with little more than a contented sigh; the parents make their choice so smoothly and without having to belabor things with words, it almost doesn't register as a significant plot point. It's just something that happens. That's really what Shoplifters is: just things happening, and the Shibatas relying on the support they get from each other to cope with those things.

Tributes to the strength of family ties are nothing new, of course. What sets Shoplifters out is not at any points its originality, but the simple excellence of its execution. This is an extremely well-made film, particularly in its deceptively simple use of the camera to absorb as much of the Shibata home as possible. Kore-eda is especially concerned with creatingh a dense mise en scène that presents this household as a cluttered and welcoming space, in which nobody has enough room or anything like privacy. It's warm even as it feels heavy with the possibility of future conflict. In part, this is because we know we're watching a movie, and some shoe is going to have to drop. But it's also simply because we know that people can't actually live like this, and the comfort and happiness and family affection on display are laced through with minimalistically-expressed annoyance and resentment. The film boasts a truly great cast, one of the best I've seen all year: they're operating almost entirely at the level of who steals a glance at whom, what triggers a quick, toothy smile, and other quiet, casual beats. When the film demands more, they rise to the occasion effortlessly, as when Kiki has to play Hatsue play-acting as a nice old lady, or when Matsuoka deals with the film's strangest and possibly most beautiful and best scene, as Aki cradles the head of one of her clients, trying to encourage him in conversation, and falling instead into a reverie of her own.

The film is tremendously pleasurable simply as an opportunity to watch, in impeccably formed long (but not too long) takes, the behavior of a curiously functional dysfunctional family, not at all unlike the same director's 2004 Nobody Knows. And then the shift happens, and it's one punch to the gut until the movie ends. I am not sure that this is all honest; Kore-eda almost seems to be daring us to accept the revelations we receive, which feel both inevitable and arbitrary, and smack of misery porn without actually quite getting there. For one, nobody actually seems all that miserable, just aware that things have gone wrong in the exact way that they would do, if they were to go wrong. For another, the director suddenly shifts the rhythm of the film, which suddenly feels like we're spiraling of a cliff after having been sitting very still for hours. The movie starts to race through things that we can't stop or slow down any more than the characters do, and it only stops to allow us to absorb the full impact of its final couple of scenes, which matter-of-factly remind us that right and wrong can be very tricky to pin down and not what they sound like on paper, and the world is a lousy place that can be made just a little bit better by surrounding yourself with the kind of people who'll support you. It's impossibly heartbreaking, maybe just a bit too manipulative; but maybe also exactly manipulative enough. It is, at any rate, a film I eagerly look forward to visiting again sometime, just as soon as my soul can stand it.

Categories: domestic dramas, japanese cinema, palme d'or winners