Hammer Horror: I was a Spanish werewolf

Over the course of its horror-film heyday (1957-1974), Hammer Film Productions made four mummy films, seven Frankenstein films, two Jekyll & Hyde adaptations, three movies about evil cults, and a whopping 17 vampire pictures, nine of them involving Count Dracula. That covers most of the classic movie monsters, except for one: the werewolf. And as has been noted by many a critic before myself, Hammer made one and only one werewolf film in all its long years as a horror factory, despite how perfectly werewolves fit snugly into the studio's wheelhouse of moody, nighttime horror films set in misty Mitteleuropean backwaters.

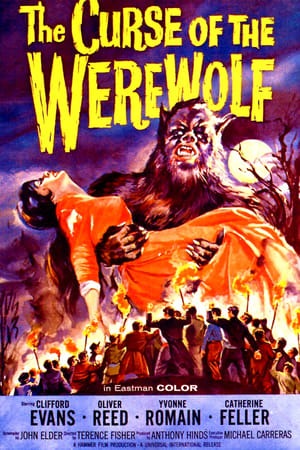

I might even go further, and say that Hammer only really made one-half of a werewolf movie. For that is perhaps the single most noteworthy thing about 1961's The Curse of the Werewolf: it has absolutely no goddamn idea what it wants its story to be. Maybe this is a good bargain: for an investment of just 93 minutes, it gives you no fewer than three distinct movies. In practice, unfortunately, it means that 50 of those 93 minutes are nothing but a waiting game, watching as the film spins around and around shuffling through plot points disconnected in all but the most tenuous ways. One could be generous and suggest that this was an attempt by producer Anthony Hinds, screenwriting under his usual pseudonym of "John Elder", to re-create the floating non-rhythm of a folktale, an approach well-suited to a werewolf story if it's well-suited to any movie monster. Or perhaps the source novel by Guy Endore, The Werewolf of Paris, has a similar free-for-all structure (my suspicion is that it's more a matter of Hinds badly condensing the novel into a much smaller form). Whatever the impulse the result is a movie that's a meandering slog for a thin majority of its running time, and simply isn't good enough once it abruptly snaps into focus to retroactively overwrite all that slogging.

So, plot one: 200 years ago, in Spain (according to a narrator who is later revealed to be a character within the movie, one who is presumably not 250 years old), there was a cruel nobleman, the Marques Siniestro (Anthony Dawson). And there is also a wretched old beggar (Richard Wordsworth), who wanders into the town that's the seat of Siniestro's marquisate, only to encounter a traditional Hammer picture's worth of suspicious locals demanding in angry, frightened tones that the beggar should just keep on traveling. But in his simplicity, the beggar decides that, this being the night of the marques's wedding feast, he might be feeling charitable. This turns out not to be the case: Siniestro amuses himself by humiliating the beggar for a few minutes, and then throws the man into his dungeons, to be forgotten for fifteen years. His only human contact for those years is the jailer (Denis Shaw), and the jailer's beautiful mute daughter (Yvonne Romain). Once the jailer is dead and the girl grown to womanhood, Siniestro - by this point a failing pile of greying flesh - attempts to force himself on her, but she resists, and is thus thrown into prison herself. The beggar, long since driven mad, and with no other remaining human emotion other than lust, rapes her, and then dies on the spot. Upon her release, the young woman kills Siniestro and flees, arriving at the home of the kind Don Alfredo Corledo (Clifford Evans), who lives alone with his housekeeper Teresa (Hira Talfrey). Despite Teresa's best efforts, the woman dies in childbirth, on Christmas Day - a most accursed combination of events.

Plot two involves the baby born that night, Leon (Justin Walters), who at around the age of 10 begins to manifest the results of that curse. He's having dreams where he is a wolf, and livestock is being slaughtered by a wolf at more or less the same time. When Leon starts to manifest thick brown hair on his forearms and palms, it becomes obvious that he is, indeed, a werewolf, having been infested by demonic forces at the time of his misbegotten birth. The only solution is for Don Alfredo and Teresa to raise him as their own, in a kind of ad hoc family, so that the power of love will keep the evil at bay.

Plot three is, in fairness, basically a direct follow-up to plot two. But also in fairness, plot one was kind of two plots, so my overall count remains the same. Another ten years or so later, Leon has grown to young adulthood, and is now played by Oliver Reed, in the first major role of his career. From here, the action isn't too terribly far afield from the werewolf movie par excellence, Universal's 1941 production of The Wolf Man: the man with the werewolf curse is stricken with guilt, his father is powerless to help, the wolf man is forced to keep suicide around as an option if a cure won't present itself, there's a pretty girl who serves as an emblem of hope. In this case, that's Christina (Catherine Feller), who is engaged to another man, but Leon dares allow himself to dream that if she falls in love with him, that might be enough to drive out the evil from his soul once and for all.

It's not the case that this third and final sequence of The Curse of the Werewolf is an all-time terrific horror movie or anything, particularly when it's so easy to compare it directly with The Wolf Man and find it wanting (I suppose I should be charitable and allow the possibility that one might compare the two and find this better). But it is very much like the thing that drifts into your mind when you hear the phrase "Hammer's werewolf movie" and feel happy thoughts. For one thing, the sets are stellar - I presume they were reused in this or that other Gothic film, because that's true of all the big-scale sets in Hammer's possession, and they seem to have energised director Terence Fisher quite a lot; his work here is far more complex than in his immediate prior horror film at Hammer, 1960's The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll. The work that Fisher puts into keeping the film trained around Leon's perspective, hiding the wolf transformation and also using subjective angles to suggest the weight bearing down on the young man, is really superb, and even in the more blatantly unacceptable parts of the movie in its opening act, he and his crew at least manage to present Siniestro's lair as appropriately dank and cobwebby.

The film also benefits from the inspired casting of Reed, who we might say was typecast as a man barely able to keep his belligerent demons in check from bursting out and destroying everything around him. But of course, in 1961, we didn't know that. Reed was just a bit player who had mostly played various anonymous tough guys in one-scene appearances. Giving him the plum role of the lycanthropy-suffering romantic hero was undoubtedly a risk, and one that paid off thoroughly for the studio: Leon's agony and rage are the best thing in the film, and it's far too easy to imagine that aspect of the character withering up and dying in the hands of most of Hammer's ineffectual pretty boys.

So yeah: the last 43 minutes of The Curse of the Werewolf are pretty damn good. The question is how much better they are than the 50 preceding minutes are a tedious grind, and I confess that I don't have an answer to that. At least the film looks nice, thanks to Fisher and cinematographer Arthur Grant. But there is tangibly little plot until the mute pregnant woman arrives at Don Alfredo's, with things happening more or less at random. Siniestro is a note of unpleasantly antagonistic camp where the film neither asks for such a thing nor benefits from it; the beggar is underdeveloped and frankly incoherent, with the one-two punch of his assault on the young woman and his immediate death only serving to emphasise how he's nothing but a plot contrivance. And one who is almost entirely associated with pointlessly morally noxious material in all his scenes, to boot.

One has to give credit to Hinds for his wild ambition: The Curse of the Werewolf is certainly trying for a whole lot. But it misses most of its targets, and the result is, if my math is correct, the earliest Hammer horror film that's not particularly successful. And I suppose that some film had to fill that spot, but it's a bit sad to have seen such a thing with my own eyes.

I might even go further, and say that Hammer only really made one-half of a werewolf movie. For that is perhaps the single most noteworthy thing about 1961's The Curse of the Werewolf: it has absolutely no goddamn idea what it wants its story to be. Maybe this is a good bargain: for an investment of just 93 minutes, it gives you no fewer than three distinct movies. In practice, unfortunately, it means that 50 of those 93 minutes are nothing but a waiting game, watching as the film spins around and around shuffling through plot points disconnected in all but the most tenuous ways. One could be generous and suggest that this was an attempt by producer Anthony Hinds, screenwriting under his usual pseudonym of "John Elder", to re-create the floating non-rhythm of a folktale, an approach well-suited to a werewolf story if it's well-suited to any movie monster. Or perhaps the source novel by Guy Endore, The Werewolf of Paris, has a similar free-for-all structure (my suspicion is that it's more a matter of Hinds badly condensing the novel into a much smaller form). Whatever the impulse the result is a movie that's a meandering slog for a thin majority of its running time, and simply isn't good enough once it abruptly snaps into focus to retroactively overwrite all that slogging.

So, plot one: 200 years ago, in Spain (according to a narrator who is later revealed to be a character within the movie, one who is presumably not 250 years old), there was a cruel nobleman, the Marques Siniestro (Anthony Dawson). And there is also a wretched old beggar (Richard Wordsworth), who wanders into the town that's the seat of Siniestro's marquisate, only to encounter a traditional Hammer picture's worth of suspicious locals demanding in angry, frightened tones that the beggar should just keep on traveling. But in his simplicity, the beggar decides that, this being the night of the marques's wedding feast, he might be feeling charitable. This turns out not to be the case: Siniestro amuses himself by humiliating the beggar for a few minutes, and then throws the man into his dungeons, to be forgotten for fifteen years. His only human contact for those years is the jailer (Denis Shaw), and the jailer's beautiful mute daughter (Yvonne Romain). Once the jailer is dead and the girl grown to womanhood, Siniestro - by this point a failing pile of greying flesh - attempts to force himself on her, but she resists, and is thus thrown into prison herself. The beggar, long since driven mad, and with no other remaining human emotion other than lust, rapes her, and then dies on the spot. Upon her release, the young woman kills Siniestro and flees, arriving at the home of the kind Don Alfredo Corledo (Clifford Evans), who lives alone with his housekeeper Teresa (Hira Talfrey). Despite Teresa's best efforts, the woman dies in childbirth, on Christmas Day - a most accursed combination of events.

Plot two involves the baby born that night, Leon (Justin Walters), who at around the age of 10 begins to manifest the results of that curse. He's having dreams where he is a wolf, and livestock is being slaughtered by a wolf at more or less the same time. When Leon starts to manifest thick brown hair on his forearms and palms, it becomes obvious that he is, indeed, a werewolf, having been infested by demonic forces at the time of his misbegotten birth. The only solution is for Don Alfredo and Teresa to raise him as their own, in a kind of ad hoc family, so that the power of love will keep the evil at bay.

Plot three is, in fairness, basically a direct follow-up to plot two. But also in fairness, plot one was kind of two plots, so my overall count remains the same. Another ten years or so later, Leon has grown to young adulthood, and is now played by Oliver Reed, in the first major role of his career. From here, the action isn't too terribly far afield from the werewolf movie par excellence, Universal's 1941 production of The Wolf Man: the man with the werewolf curse is stricken with guilt, his father is powerless to help, the wolf man is forced to keep suicide around as an option if a cure won't present itself, there's a pretty girl who serves as an emblem of hope. In this case, that's Christina (Catherine Feller), who is engaged to another man, but Leon dares allow himself to dream that if she falls in love with him, that might be enough to drive out the evil from his soul once and for all.

It's not the case that this third and final sequence of The Curse of the Werewolf is an all-time terrific horror movie or anything, particularly when it's so easy to compare it directly with The Wolf Man and find it wanting (I suppose I should be charitable and allow the possibility that one might compare the two and find this better). But it is very much like the thing that drifts into your mind when you hear the phrase "Hammer's werewolf movie" and feel happy thoughts. For one thing, the sets are stellar - I presume they were reused in this or that other Gothic film, because that's true of all the big-scale sets in Hammer's possession, and they seem to have energised director Terence Fisher quite a lot; his work here is far more complex than in his immediate prior horror film at Hammer, 1960's The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll. The work that Fisher puts into keeping the film trained around Leon's perspective, hiding the wolf transformation and also using subjective angles to suggest the weight bearing down on the young man, is really superb, and even in the more blatantly unacceptable parts of the movie in its opening act, he and his crew at least manage to present Siniestro's lair as appropriately dank and cobwebby.

The film also benefits from the inspired casting of Reed, who we might say was typecast as a man barely able to keep his belligerent demons in check from bursting out and destroying everything around him. But of course, in 1961, we didn't know that. Reed was just a bit player who had mostly played various anonymous tough guys in one-scene appearances. Giving him the plum role of the lycanthropy-suffering romantic hero was undoubtedly a risk, and one that paid off thoroughly for the studio: Leon's agony and rage are the best thing in the film, and it's far too easy to imagine that aspect of the character withering up and dying in the hands of most of Hammer's ineffectual pretty boys.

So yeah: the last 43 minutes of The Curse of the Werewolf are pretty damn good. The question is how much better they are than the 50 preceding minutes are a tedious grind, and I confess that I don't have an answer to that. At least the film looks nice, thanks to Fisher and cinematographer Arthur Grant. But there is tangibly little plot until the mute pregnant woman arrives at Don Alfredo's, with things happening more or less at random. Siniestro is a note of unpleasantly antagonistic camp where the film neither asks for such a thing nor benefits from it; the beggar is underdeveloped and frankly incoherent, with the one-two punch of his assault on the young woman and his immediate death only serving to emphasise how he's nothing but a plot contrivance. And one who is almost entirely associated with pointlessly morally noxious material in all his scenes, to boot.

One has to give credit to Hinds for his wild ambition: The Curse of the Werewolf is certainly trying for a whole lot. But it misses most of its targets, and the result is, if my math is correct, the earliest Hammer horror film that's not particularly successful. And I suppose that some film had to fill that spot, but it's a bit sad to have seen such a thing with my own eyes.

Categories: british cinema, costume dramas, hammer films, horror, werewolves