The suburban jungle

Nicole Holofcener is not a name-brand film auteur, but she really should be. Her films, which come out at a fairly steady once-every-five-years clip, are clearly the work of a single mind, tidily unifying her approach to the messy business of humanity by showing people in profound disarray through the lens of quiet, unhurried, unfussy little cosmopolitan fables that call no attention to themselves in any way, except for the profound richness of human feeling being pressed out of actors being permitted to play everything as small as can be imagined. They are some of the very best of a certain branch of cinema-for-adults that's too prim and precise to feel exactly "realist", too stripped of extreme plot developments to feel like anything else. They are, I can only think to say, Nicole Holofcener films. And her sixth movie in a 22-year-span, The Land of Steady Habits, is absolutely no exception to the rule. This despite breaking from her other five movies in no fewer than three tremendously important ways: it's her first movie with a male protagonist, her first without Catherine Keener appearing in any role whatsoever (if that doesn't sound like a big deal, then you plainly haven't seen a Holofcener/Keener picture), and her first to be adapted from somebody else's story, Ted Thompson's 2014 novel of the same title.

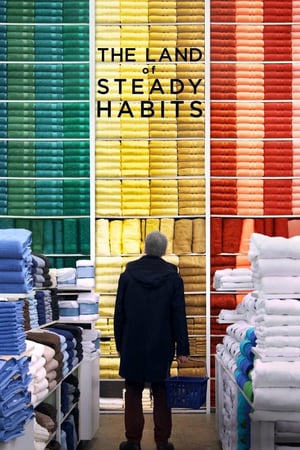

Despite all of this, it's clear we're in Holofcener World from the very first shot, a real marvel of dry comic understatement: it's a composition pointing straight at a wall of towels in a Bed, Bath & Beyond,* neatly ordered as a regimented, ersatz rainbow, which than pans a crisp, mechanical 90° to the left to find Anders Hill (Ben Mendelsohn) staring at the towels with a slightly confused, alarmed expression, that can be read as anything from why are there so many towel choices? to I can't believe I'm here buying towels at this stage of my life to maybe I'll die and then I don't need to worry about towels anymore. There's something wild and ecstatic here, a strange way to feel about such a clamped-down, deliberately plain opening image, but it's got so much inside of it: the merry riot of colors of the towels, clashing with the lifeless white shelving and floor that communicate "chain retail store" with antiseptic fury; the contrast between the pre-packaged bonhomie promised by the neatly-laid out rows of home goods and Anders's gutted-fish expression; even the pan itself, a little jolt of hard ironic comedy in context.

It's a splendid opening gambit for a film that will spent a very pleasantly curt 98 minutes examining this man in all of his merits (of which there are few to start) and flaws (which he exacerbates), and the very particular culture of upper-middle class social codes that created and destroyed him. For aye, when we first meet Anders, he has already been destroyed. The film's title is a longstanding reference to the more well-to-do enclaves of Connecticut, and in this very particular case, it refers mostly to the way that people can be on the wrong track, realise they're on the wrong track, watch themselves making a bad situation worse with their choices, and not budge an inch from their current behaviors, because eh, that's just what you do. This is certainly true of Anders, whom we meet about a year or six months after his divorce from Helene (Edie Falco), for no other reason than because he was bored and wanted a shake-up. Now he's still bored, and a social pariah on top of it.

Generic sad-sack middle-aged white guy stuff, it sounds like, but for a couple of key things. First, it's not a sad sack movie. Anders is a sad sack, without a doubt, but the movie has Holofcener's immaculately delicate touch to guide it, and she's probably never made such a tonally tricky film. Generally, her stock in trade has been upbeat comedies with a bittersweet spike; The Land of Steady Habits is sufficiently laconic, and heads into some sufficiently dark places near the end, that I don't think it could be called a "comedy" at all; but it is a very light, glancing drama. It's also a film that has a terribly, wonderfully fussy relationship to its main character, which is the second thing: there's nothing generic about Anders. The film expertly manages the trick of empathising with him as a human, while finding all of his actions ill-advised, selfish, and more to the point, simply foolish; which is part of the empathy, since he finds his actions to be much the same thing. Mendelsohn's presence is a huge boon to the film: I wouldn't say that there's anything truly stunning and unexpected in the performance, but it's an exceedingly well-executed stock type. This is a character who thinks he lives entirely in his own head, but whose self-loathing and miserable asshole attitude have grown so extreme over the years that they express themselves in all kinds of unintended ways: his way of working his mouth like he wants to talk but doesn't, his hollow stare, looking in the direction of people rather than at them, and looking in their direction substantially longer than is pleasant. It's a great embodiment of somebody so used to being passive-aggressive that he's forgotten that he's doing it, and the smallness is an excellent change of pace for a world-class actor who has gotten himself a bit too typecast as sociopaths and other villains. Anders is no sociopath; he's just a guy who didn't like his life, tried to blow it up, and found to his horror that he succeeded.

The film around him finds Holofcener and company doing superb work capturing the cadences of a particular stratum of American life, and injecting it with a hint of despair; one of the things she's been repeatedly good at, especially in 2006's Friends with Money and 2010's Please Give, is depicting the social gamesmanship of people who don't want to be found out as being even slightly less well-off than they claim to be, and The Land of Steady Habits falls squarely into that tradition. Anders and Helene have a 27-year-old son, Preston (Thomas Mann), who had a good education and fucked everything up on drugs, and he ends up being a rather obvious surrogate for Anders's own feelings of much more subtle social ostracism; they both are further echoed by Charlie (Charlie Tahan), the teenage son of Helene's best friend Sophie (Elizabeth Marvel), who's full of the Great American Hatred of Suburbia, but hasn't found a way to articulate that in a healthy way. The film's most conspicuous flaw is probably how it handles these two characters; the Three Ages of Mediocre Men theme is much too overt, and the film's uncertainty as to whether Preston and Charlie are main characters in their own right, or if they only matter as dark mirrors of Anders, leads to a lot of time spent on scenes that don't feel like they're very productive. The film is so good at standing alongside Anders without ever quite aligning itself to him; it can't manage that with the other characters, and it's very much best off when it's not obviously trying to.

That being said, this is hardly all Mendelsohn's show, even if he's giving the best performance: it's a terrific ensemble, with lots of great work from folks like Marvel and Connie Britton (as a woman Anders starts haplessly dating) giving strong personalities to characters who only partially exist on the page. The film, like every Holofcener film, is generous to all of its characters without failing to notice when they're being wrong (that it manages to avoid taking sides between Helene and Anders, instead simply watching them snipe at each other, is a considerable achievement), and like every Holofcener film, it has such an acute sense of who these people are and how they behave and what drives them to do it that watching character interactions, devoid of any but the most glancing narrative importance, becomes the most interesting stuff imaginable. It's overall a slightly odd turn for the director, and I particularly hope that she embraces outright comedy more next time, but it's pretty much all I wanted from the five-year wait since her last feature, Enough Said: interesting and not always likable people living their lives, behaving as they must, and not feeling at all like the pressures of being in a scripted movie are causing them to do anything. It is a calming movie even at its most dire, and a simply lovely way to start the 2018 Serious Movie season.

*To my readers who haven't the joys and sorrows of life among the strip malls of suburban America: Bed, Bath & Beyond is a store where you can buy all of your home goods, always finding above-average but never terrific products at fair but never great prices, and every square foot of the place is filled with a kind of mildly hostile ennui. I cannot recall the last time that a specific consumer reference was so immediately and necessary to establishing a very particular milieu in a film: our protagonist is someone who would end up at a Bed, Bath & Beyond but not a Pottery Barn or a Sur La Table on the one hand, not a Target or a Costco on the other hand, and this matters a great deal.

Despite all of this, it's clear we're in Holofcener World from the very first shot, a real marvel of dry comic understatement: it's a composition pointing straight at a wall of towels in a Bed, Bath & Beyond,* neatly ordered as a regimented, ersatz rainbow, which than pans a crisp, mechanical 90° to the left to find Anders Hill (Ben Mendelsohn) staring at the towels with a slightly confused, alarmed expression, that can be read as anything from why are there so many towel choices? to I can't believe I'm here buying towels at this stage of my life to maybe I'll die and then I don't need to worry about towels anymore. There's something wild and ecstatic here, a strange way to feel about such a clamped-down, deliberately plain opening image, but it's got so much inside of it: the merry riot of colors of the towels, clashing with the lifeless white shelving and floor that communicate "chain retail store" with antiseptic fury; the contrast between the pre-packaged bonhomie promised by the neatly-laid out rows of home goods and Anders's gutted-fish expression; even the pan itself, a little jolt of hard ironic comedy in context.

It's a splendid opening gambit for a film that will spent a very pleasantly curt 98 minutes examining this man in all of his merits (of which there are few to start) and flaws (which he exacerbates), and the very particular culture of upper-middle class social codes that created and destroyed him. For aye, when we first meet Anders, he has already been destroyed. The film's title is a longstanding reference to the more well-to-do enclaves of Connecticut, and in this very particular case, it refers mostly to the way that people can be on the wrong track, realise they're on the wrong track, watch themselves making a bad situation worse with their choices, and not budge an inch from their current behaviors, because eh, that's just what you do. This is certainly true of Anders, whom we meet about a year or six months after his divorce from Helene (Edie Falco), for no other reason than because he was bored and wanted a shake-up. Now he's still bored, and a social pariah on top of it.

Generic sad-sack middle-aged white guy stuff, it sounds like, but for a couple of key things. First, it's not a sad sack movie. Anders is a sad sack, without a doubt, but the movie has Holofcener's immaculately delicate touch to guide it, and she's probably never made such a tonally tricky film. Generally, her stock in trade has been upbeat comedies with a bittersweet spike; The Land of Steady Habits is sufficiently laconic, and heads into some sufficiently dark places near the end, that I don't think it could be called a "comedy" at all; but it is a very light, glancing drama. It's also a film that has a terribly, wonderfully fussy relationship to its main character, which is the second thing: there's nothing generic about Anders. The film expertly manages the trick of empathising with him as a human, while finding all of his actions ill-advised, selfish, and more to the point, simply foolish; which is part of the empathy, since he finds his actions to be much the same thing. Mendelsohn's presence is a huge boon to the film: I wouldn't say that there's anything truly stunning and unexpected in the performance, but it's an exceedingly well-executed stock type. This is a character who thinks he lives entirely in his own head, but whose self-loathing and miserable asshole attitude have grown so extreme over the years that they express themselves in all kinds of unintended ways: his way of working his mouth like he wants to talk but doesn't, his hollow stare, looking in the direction of people rather than at them, and looking in their direction substantially longer than is pleasant. It's a great embodiment of somebody so used to being passive-aggressive that he's forgotten that he's doing it, and the smallness is an excellent change of pace for a world-class actor who has gotten himself a bit too typecast as sociopaths and other villains. Anders is no sociopath; he's just a guy who didn't like his life, tried to blow it up, and found to his horror that he succeeded.

The film around him finds Holofcener and company doing superb work capturing the cadences of a particular stratum of American life, and injecting it with a hint of despair; one of the things she's been repeatedly good at, especially in 2006's Friends with Money and 2010's Please Give, is depicting the social gamesmanship of people who don't want to be found out as being even slightly less well-off than they claim to be, and The Land of Steady Habits falls squarely into that tradition. Anders and Helene have a 27-year-old son, Preston (Thomas Mann), who had a good education and fucked everything up on drugs, and he ends up being a rather obvious surrogate for Anders's own feelings of much more subtle social ostracism; they both are further echoed by Charlie (Charlie Tahan), the teenage son of Helene's best friend Sophie (Elizabeth Marvel), who's full of the Great American Hatred of Suburbia, but hasn't found a way to articulate that in a healthy way. The film's most conspicuous flaw is probably how it handles these two characters; the Three Ages of Mediocre Men theme is much too overt, and the film's uncertainty as to whether Preston and Charlie are main characters in their own right, or if they only matter as dark mirrors of Anders, leads to a lot of time spent on scenes that don't feel like they're very productive. The film is so good at standing alongside Anders without ever quite aligning itself to him; it can't manage that with the other characters, and it's very much best off when it's not obviously trying to.

That being said, this is hardly all Mendelsohn's show, even if he's giving the best performance: it's a terrific ensemble, with lots of great work from folks like Marvel and Connie Britton (as a woman Anders starts haplessly dating) giving strong personalities to characters who only partially exist on the page. The film, like every Holofcener film, is generous to all of its characters without failing to notice when they're being wrong (that it manages to avoid taking sides between Helene and Anders, instead simply watching them snipe at each other, is a considerable achievement), and like every Holofcener film, it has such an acute sense of who these people are and how they behave and what drives them to do it that watching character interactions, devoid of any but the most glancing narrative importance, becomes the most interesting stuff imaginable. It's overall a slightly odd turn for the director, and I particularly hope that she embraces outright comedy more next time, but it's pretty much all I wanted from the five-year wait since her last feature, Enough Said: interesting and not always likable people living their lives, behaving as they must, and not feeling at all like the pressures of being in a scripted movie are causing them to do anything. It is a calming movie even at its most dire, and a simply lovely way to start the 2018 Serious Movie season.

*To my readers who haven't the joys and sorrows of life among the strip malls of suburban America: Bed, Bath & Beyond is a store where you can buy all of your home goods, always finding above-average but never terrific products at fair but never great prices, and every square foot of the place is filled with a kind of mildly hostile ennui. I cannot recall the last time that a specific consumer reference was so immediately and necessary to establishing a very particular milieu in a film: our protagonist is someone who would end up at a Bed, Bath & Beyond but not a Pottery Barn or a Sur La Table on the one hand, not a Target or a Costco on the other hand, and this matters a great deal.