Blockbuster History: Nazi hunters

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the true story of how infamous war criminal Adolf Eichmann was captured by the Mossad is related in Operation Finale, the latest in an intermittent line of films about post-war Nazis both real and fictional being found out and brought to justice. Our present subject is certainly not the best of these, but it is maybe the most bonkers.

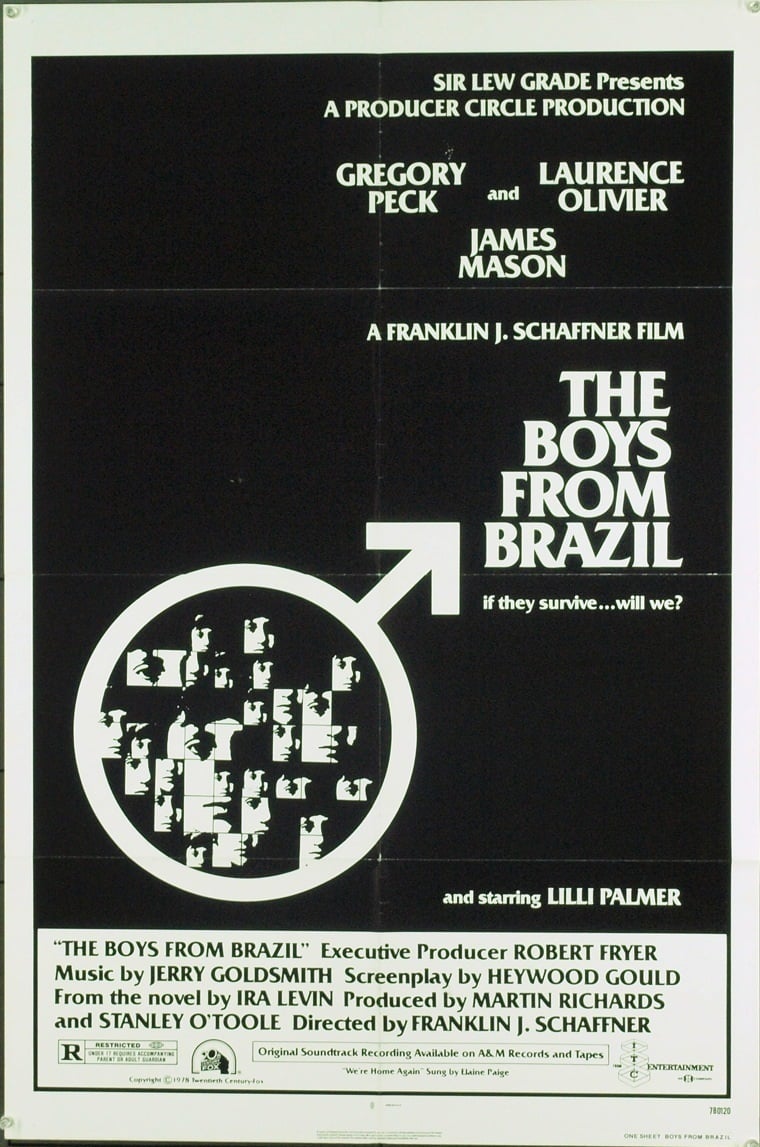

In its own little way, the 1978 film adaptation of Ira Levin's 1976 novel The Boys from Brazil makes history. For here, and only here, do we get to see a film that is at its very best when Steve Guttenberg is around, and which takes a huge step down in quality right around the point that James Mason enters the cast. And that's to say nothing of Gregory Peck and Laurence Olivier, who are both in the film much more than Mason is, and are much worse. Peck, Olivier, Mason - that is a fucking AAA platinum-level set of names to set before the title of a movie, and they are all three out-acted by Steve Guttenberg; in just his second credited feature film appearance no less. If you need proof that all things are possible in an infinite universe, there it is.

As to what exactly led such an august trio down such embarrassing paths, I cannot quite say. Perhaps, indeed, it is because they are an august trio, and The Boys from Brazil would maybe benefit from being a bit less august. The film clearly has aspirations to doing something at least somewhat more respectable than the usual genre film: besides assembling that headlining cast, the producers arranged for the film to be directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, who had in the previous decade won an Oscar of his own for the 1970 Best Picture winner Patton, and gotten 1971's Nicholas and Alexandra to a Best Picture nomination, before helming the very admirable and serious literary adaptations Papillon and Islands in the Stream. It's also the third and last adaptation in a decade-long wave of Levin adaptations, with the previous two - 1968's Rosemary's Baby and 1975's The Stepford Wives - standing tall as exactly the kind of genre fare that could have been very grungy and tacky, but which are treated with utmost gravity and prestige, and this is self-evidently the territory that The Boys from Brazil hoped to occupy itself. Hell, it even got the very specific release date of the first weekend in October that this very day serves as harbor to films that might be good Oscar plays if they turn out right, but it's just far enough from Oscar season that if they misfire, nobody's going to feel particularly embarrassed.

And if The Boys from Brazil misfired, it was only by a little: the film in fact received three Oscar nominations, for Olivier and editor Robert Swink and composer Jerry Goldsmith. Which is a little ironic, given that Olivier and the editing are two of the film's most conspicuous flaws. At some point, I should really pay off all the innuendo of that opening paragraph and just dive into the acting, because it really is the case that the difference between a Boys from Brazil that is at least kind of solid and the dreary, if intermittently hilarious, Boys from Brazil we have, is almost entirely on the two lead actors. The thing is, the story itself is actually pretty solid: there's an old Jewish Nazi hunter, Ezra Lieberman (Olivier) whose great triumph of identifying former death camp guard Frieda Maloney (Uta Hagen) was sufficiently unimpressive that most people, including the wealthy Israelis who have funded his work, are beginning to question whether the business of trying a bunch of sixtysomething retires for war crimes is really worth the effort. But at least one young, passionate Jewish American, Barry Kohler (Guttenberg) has taken to Lieberman as something of an unofficial mentor, and has lately been bothering the old man with reports from Paraguay, where he's dug up info that a for-real A-list Nazi is going to be showing up. Lieberman dismisses the boy, but Kohler's right: none other than Dr. Josef Mengele (Peck), the most infamous Nazi still at large, is suddenly out in the relative open. Turns out that the time has come for an experiment Mengele started over a decade ago to enter its second phase: he is ordering his most trusted assassins to kill 94 old men, all of them 65-year-old civil servants, all of them Gentiles, over the next two and a half years. In so doing, he is going to carefully control the environmental development of those men's sons, though even that fact comes out rather later in the film, and the reason he cares comes out later still.

Not that it's hard to figure out; and besides, much as is the case with The Stepford Wives, the thing that most people know about The Boys from Brazil is its shocking twist, which in this case is that Mengele has 94 clones of Adolf Hitler in North America and Europe, and is trying to precisely re-create the life and upbringing of the historic Hitler in the hopes that at least one of those 94 will be an exact replica in personality and accomplishment of his beloved Führer. And honestly, that's more than a little bit interesting, as plot hooks go: the maddest mad scientist in history turning all the world into his laboratory so that he can bring back to life modern history's most notorious psychopath. It's basically just a more scientifically grounded and elaborate version of They Saved Hitler's Brain, and I will always find my attention perk up when a truly shoddy, trashy, lurid B-movie premise like "an army of Hitler clones" gets treated with some crafty plotting and relatively grounded science. The Boys from Brazil benefits very little from making the Hitler clone angle a surprise - it especially serves to make Lieberman seem a bit dim and slow on the uptake - but even before the full scale of Mengele's plot is revealed, there's still enough inherently interesting material in watching him loom over the world like a chessmaster, with only one doddering old man trying to stop him.

Let's go back to those words I just used. "Shoddy, trashy, lurid". Now, when all is said and done, this is still a sci-fi movie about Josef Mengele, who was still alive and in hiding when the book and movie came out (he died of a swimming accident in 1979). And that requires a remarkable level of care: do you go for the extremely sober, sincere approach, treating Mengele's evil with the least sensational kind of filmmaking you can manage, or do you go for gonzo exploitation film excess, leaning into the tastelessness of what you're doing? I would suggest that "army of Hitler clones" has more or less made that choice for you, but it's no surprise given all the people involved in making it that The Boys from Brazil has decided to go the other direction, to be as stentorian and grounded as it might. And this could work: the film's production values are unmistakably high, and the sets and location photography (with Portugal playing Paraguay, along with various parts of Austria, London, and the U.S. east coast playing themselves) imbue the film with substantial presence and realism. Mengele's office, in particular, is a fine achievement of design, austere and impersonal in its walls full of grids with dates, photographs of organs, and such, and then there's the giant painting of Hitler overlooking a bust of Hitler that comes as a shocking reminder of this man's particular depravities.

This could work. It doesn't work, and that has almost everything to do with Olivier and Peck (Mason, despite his third billing, has more of very extended cameo as Mengele's increasingly impatient handler from the shadowy high command of Nazis in exile; his performance, which is merely bored and detached from the movie, is also a great deal less flagrantly bad than the other two). They represent two entirely different, equally bad approaches to this material. Peck's is relatively the more grounded, but it's wildly inconsistent: he oscillates between his famous Peckian taciturn line readings and firm, upright posture with explosions of rage that feel less true to the character and more about underlying how very demented Mengele is. Basically, Peck has apparently committed the great sin of deciding that since he knows that his character is evil, his character knows it as well, and so he plays Mengele basically as a melodrama villain constrained by the natural dignity of a Peck character. It's a terrible fit for the generally sedate, realistic film.

But it's not nearly as terrible as what Olivier is up to. Olivier is more consistent than Peck; consistently outrageous and unbelieveable, at least. He's glommed on to a German-Jewish accent that makes him sound more like the bad guy from a WWII-era Bugs Bunny cartoon, turning every "S" in sight into a shrill, hissing "Z", and pitch every last beat of his performance, from the line readings to the reaction shots, to the back row of a theater. And not a 20th Century theater. A 19th Century music hall where they play only the most florid mellerdrammers. It bears noticing that Lieberman comes right in the middle between Olivier's role as an ex-Nazi in Marathon Man and his weeping rabbi father in the Neil Diamond version of The Jazz Singer, and he is far, far close to the broad "I! Haff! No! Son!" excesses of the latter than his relatively constrained, clipped performance in the former. The accent is the most obviously objectionable part of Olivier's performance, along with his big hammy cadences - for example, he is able to take a genuinely excellent line of dialogue, like "Mr. Kohler, it may be a blinding revelation to you that there are Nazis in Paraguay, but I assure you, it is no news to me. And if you stay there much longer, there will still be Nazis in Paraguay, but there will be one less Jewish boy in the world", and turn it into a bit of nonsensical, sing-songy cartoon poetry. "Mister Koh-lahr, it may be a BLINDink revvelazhun to hyu..." But even so, I think it's what Olivier is doing with his eyes that annoys me the most: rolling them around with such intensity that it's a shock his whole head doesn't fall off, managing to flutter his eyelids in profound annoyance whenever anybody does anything. It is pure unbridled bullshit shtick, and in a film that knew what to do with it, could even be a genius bit of camp; but The Boys from Brazil is more or less defined by its disinterest in camp at any level. At any rate, I would not care to go around making statements like "the worst performance ever nominated for an Academy Award" without having very methodically considered and reconsidered every one in every category. But I will say at least that Olivier in The Boys from Brazil passes the smell test on that claim.

It really is almost entirely down to Olivier and Peck that the film doesn't work. It wants to be more trashy, sure, and it's way too easy to get in front of the twist, especially given how teenage non-actor Jeremy Black (playing all of the various arrogant prick clones we see, to limited distinction) has been given a Hitler-ish haircut with just a Superman spit curl to keep it from being immediately noticeable. And 124 minutes is not short for this plot. But still, it's interesting. There could be something here, with Schaffner's plain, clean directing, and Goldsmith's wonderful main theme, a waltz that's just a little bit out of time and key, to the effect that it feels frenzied and threatening rather than elegant and lively. But the two main actors, one or the other of whom is in nearly every single scene (they only share one the screen once, in a very unpersuasive fight scene), do far too much to butcher any tone the film is ever able to come up with. The result is a film too dopey and campy to be taken seriously, too mordant and sober to be much fun, and too ludicrous and melodramatic to be at all defensible as a social commentary - a perfect storm of a movie shooting itself in the foot at every turn.

In its own little way, the 1978 film adaptation of Ira Levin's 1976 novel The Boys from Brazil makes history. For here, and only here, do we get to see a film that is at its very best when Steve Guttenberg is around, and which takes a huge step down in quality right around the point that James Mason enters the cast. And that's to say nothing of Gregory Peck and Laurence Olivier, who are both in the film much more than Mason is, and are much worse. Peck, Olivier, Mason - that is a fucking AAA platinum-level set of names to set before the title of a movie, and they are all three out-acted by Steve Guttenberg; in just his second credited feature film appearance no less. If you need proof that all things are possible in an infinite universe, there it is.

As to what exactly led such an august trio down such embarrassing paths, I cannot quite say. Perhaps, indeed, it is because they are an august trio, and The Boys from Brazil would maybe benefit from being a bit less august. The film clearly has aspirations to doing something at least somewhat more respectable than the usual genre film: besides assembling that headlining cast, the producers arranged for the film to be directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, who had in the previous decade won an Oscar of his own for the 1970 Best Picture winner Patton, and gotten 1971's Nicholas and Alexandra to a Best Picture nomination, before helming the very admirable and serious literary adaptations Papillon and Islands in the Stream. It's also the third and last adaptation in a decade-long wave of Levin adaptations, with the previous two - 1968's Rosemary's Baby and 1975's The Stepford Wives - standing tall as exactly the kind of genre fare that could have been very grungy and tacky, but which are treated with utmost gravity and prestige, and this is self-evidently the territory that The Boys from Brazil hoped to occupy itself. Hell, it even got the very specific release date of the first weekend in October that this very day serves as harbor to films that might be good Oscar plays if they turn out right, but it's just far enough from Oscar season that if they misfire, nobody's going to feel particularly embarrassed.

And if The Boys from Brazil misfired, it was only by a little: the film in fact received three Oscar nominations, for Olivier and editor Robert Swink and composer Jerry Goldsmith. Which is a little ironic, given that Olivier and the editing are two of the film's most conspicuous flaws. At some point, I should really pay off all the innuendo of that opening paragraph and just dive into the acting, because it really is the case that the difference between a Boys from Brazil that is at least kind of solid and the dreary, if intermittently hilarious, Boys from Brazil we have, is almost entirely on the two lead actors. The thing is, the story itself is actually pretty solid: there's an old Jewish Nazi hunter, Ezra Lieberman (Olivier) whose great triumph of identifying former death camp guard Frieda Maloney (Uta Hagen) was sufficiently unimpressive that most people, including the wealthy Israelis who have funded his work, are beginning to question whether the business of trying a bunch of sixtysomething retires for war crimes is really worth the effort. But at least one young, passionate Jewish American, Barry Kohler (Guttenberg) has taken to Lieberman as something of an unofficial mentor, and has lately been bothering the old man with reports from Paraguay, where he's dug up info that a for-real A-list Nazi is going to be showing up. Lieberman dismisses the boy, but Kohler's right: none other than Dr. Josef Mengele (Peck), the most infamous Nazi still at large, is suddenly out in the relative open. Turns out that the time has come for an experiment Mengele started over a decade ago to enter its second phase: he is ordering his most trusted assassins to kill 94 old men, all of them 65-year-old civil servants, all of them Gentiles, over the next two and a half years. In so doing, he is going to carefully control the environmental development of those men's sons, though even that fact comes out rather later in the film, and the reason he cares comes out later still.

Not that it's hard to figure out; and besides, much as is the case with The Stepford Wives, the thing that most people know about The Boys from Brazil is its shocking twist, which in this case is that Mengele has 94 clones of Adolf Hitler in North America and Europe, and is trying to precisely re-create the life and upbringing of the historic Hitler in the hopes that at least one of those 94 will be an exact replica in personality and accomplishment of his beloved Führer. And honestly, that's more than a little bit interesting, as plot hooks go: the maddest mad scientist in history turning all the world into his laboratory so that he can bring back to life modern history's most notorious psychopath. It's basically just a more scientifically grounded and elaborate version of They Saved Hitler's Brain, and I will always find my attention perk up when a truly shoddy, trashy, lurid B-movie premise like "an army of Hitler clones" gets treated with some crafty plotting and relatively grounded science. The Boys from Brazil benefits very little from making the Hitler clone angle a surprise - it especially serves to make Lieberman seem a bit dim and slow on the uptake - but even before the full scale of Mengele's plot is revealed, there's still enough inherently interesting material in watching him loom over the world like a chessmaster, with only one doddering old man trying to stop him.

Let's go back to those words I just used. "Shoddy, trashy, lurid". Now, when all is said and done, this is still a sci-fi movie about Josef Mengele, who was still alive and in hiding when the book and movie came out (he died of a swimming accident in 1979). And that requires a remarkable level of care: do you go for the extremely sober, sincere approach, treating Mengele's evil with the least sensational kind of filmmaking you can manage, or do you go for gonzo exploitation film excess, leaning into the tastelessness of what you're doing? I would suggest that "army of Hitler clones" has more or less made that choice for you, but it's no surprise given all the people involved in making it that The Boys from Brazil has decided to go the other direction, to be as stentorian and grounded as it might. And this could work: the film's production values are unmistakably high, and the sets and location photography (with Portugal playing Paraguay, along with various parts of Austria, London, and the U.S. east coast playing themselves) imbue the film with substantial presence and realism. Mengele's office, in particular, is a fine achievement of design, austere and impersonal in its walls full of grids with dates, photographs of organs, and such, and then there's the giant painting of Hitler overlooking a bust of Hitler that comes as a shocking reminder of this man's particular depravities.

This could work. It doesn't work, and that has almost everything to do with Olivier and Peck (Mason, despite his third billing, has more of very extended cameo as Mengele's increasingly impatient handler from the shadowy high command of Nazis in exile; his performance, which is merely bored and detached from the movie, is also a great deal less flagrantly bad than the other two). They represent two entirely different, equally bad approaches to this material. Peck's is relatively the more grounded, but it's wildly inconsistent: he oscillates between his famous Peckian taciturn line readings and firm, upright posture with explosions of rage that feel less true to the character and more about underlying how very demented Mengele is. Basically, Peck has apparently committed the great sin of deciding that since he knows that his character is evil, his character knows it as well, and so he plays Mengele basically as a melodrama villain constrained by the natural dignity of a Peck character. It's a terrible fit for the generally sedate, realistic film.

But it's not nearly as terrible as what Olivier is up to. Olivier is more consistent than Peck; consistently outrageous and unbelieveable, at least. He's glommed on to a German-Jewish accent that makes him sound more like the bad guy from a WWII-era Bugs Bunny cartoon, turning every "S" in sight into a shrill, hissing "Z", and pitch every last beat of his performance, from the line readings to the reaction shots, to the back row of a theater. And not a 20th Century theater. A 19th Century music hall where they play only the most florid mellerdrammers. It bears noticing that Lieberman comes right in the middle between Olivier's role as an ex-Nazi in Marathon Man and his weeping rabbi father in the Neil Diamond version of The Jazz Singer, and he is far, far close to the broad "I! Haff! No! Son!" excesses of the latter than his relatively constrained, clipped performance in the former. The accent is the most obviously objectionable part of Olivier's performance, along with his big hammy cadences - for example, he is able to take a genuinely excellent line of dialogue, like "Mr. Kohler, it may be a blinding revelation to you that there are Nazis in Paraguay, but I assure you, it is no news to me. And if you stay there much longer, there will still be Nazis in Paraguay, but there will be one less Jewish boy in the world", and turn it into a bit of nonsensical, sing-songy cartoon poetry. "Mister Koh-lahr, it may be a BLINDink revvelazhun to hyu..." But even so, I think it's what Olivier is doing with his eyes that annoys me the most: rolling them around with such intensity that it's a shock his whole head doesn't fall off, managing to flutter his eyelids in profound annoyance whenever anybody does anything. It is pure unbridled bullshit shtick, and in a film that knew what to do with it, could even be a genius bit of camp; but The Boys from Brazil is more or less defined by its disinterest in camp at any level. At any rate, I would not care to go around making statements like "the worst performance ever nominated for an Academy Award" without having very methodically considered and reconsidered every one in every category. But I will say at least that Olivier in The Boys from Brazil passes the smell test on that claim.

It really is almost entirely down to Olivier and Peck that the film doesn't work. It wants to be more trashy, sure, and it's way too easy to get in front of the twist, especially given how teenage non-actor Jeremy Black (playing all of the various arrogant prick clones we see, to limited distinction) has been given a Hitler-ish haircut with just a Superman spit curl to keep it from being immediately noticeable. And 124 minutes is not short for this plot. But still, it's interesting. There could be something here, with Schaffner's plain, clean directing, and Goldsmith's wonderful main theme, a waltz that's just a little bit out of time and key, to the effect that it feels frenzied and threatening rather than elegant and lively. But the two main actors, one or the other of whom is in nearly every single scene (they only share one the screen once, in a very unpersuasive fight scene), do far too much to butcher any tone the film is ever able to come up with. The result is a film too dopey and campy to be taken seriously, too mordant and sober to be much fun, and too ludicrous and melodramatic to be at all defensible as a social commentary - a perfect storm of a movie shooting itself in the foot at every turn.