Once upon a time in Mexico

Want another opinion? Check out Conrado's thoughts on the film!

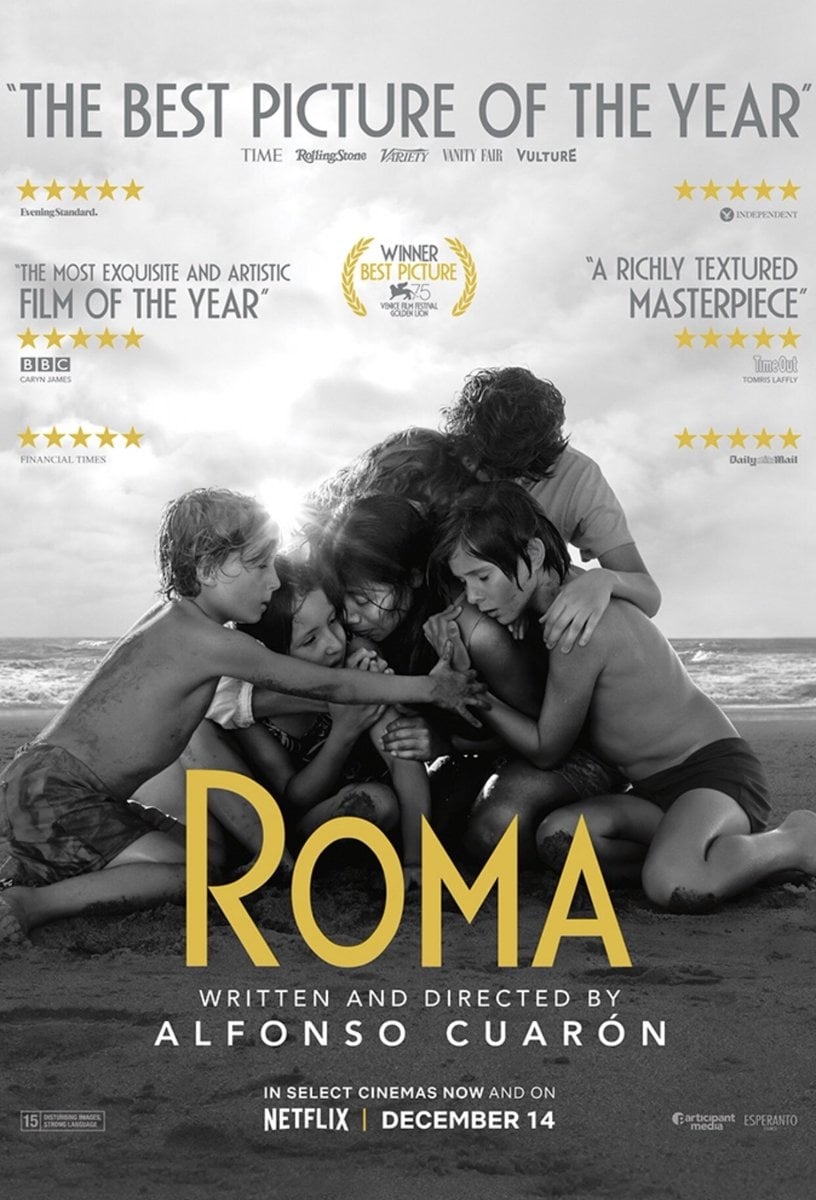

Every movie, even if just by accident, starts out by telling us how to watch it. Roma, the eighth feature film directed by Alfonso Cuarón (who also takes solo screenwriting credit), just happens to be unusually great at doing this. The film's exemplary opening shot begins as an almost completely inscrutable play of textures: a grey-on-grey diamond pattern of ceramic tiles in multiple shades overrun by shiny water. Water sounds emanating from nowhere in particular accompany the image. After a good long hold on this static composition (during which time the film's credits are all presented in a stately, Art Deco-looking font), the camera tilts up to reveal that we've been standing in a hallway whose floor is being washed by a Mixtec woman (Yalitza Aparicio) far off in the distance, at the back of a composition being shot with a just slightly wide lens to exaggerate the depth of the shot. And so gracefully that it almost doesn't register, the camera shifts to keep her centered, panning as she walks off to the left and into a house whose courtyard, it turns out, we've been standing in all along.

Virtually all of the elements we'll need to keep in mind have just been introduced to us. First, there is that woman herself, a housemaid named Cleo, inspired by the family maid of Cuarón's childhood. And there is the way Cleo is framed, a distant figure, part of the literal background; but the film requires us to notice her, as it places her in the center. It does this without pretending that it can get inside her head: it stands respectfully apart, watching her, but it does not ventriloquise her story. And let us not lose sight of the formal elements. There is the deliberate, floating quality to the camera movements, tilting and panning smoothly, guiding our attention gently but decisively (Cuarón worked as his own cinematographer, having clearly learned many wonderful from his longtime collaborator Emmanuel Lubezki). There is the crisp beauty of the black-and-white, using every delicate gradation of grey to craft something soft and dreamy, mired in a sense of the past. But at the same time, the digital sharpness of the high-resolution cameras used to shoot the film leave images so bright, clean, and solid, they feel almost uncomfortably present. The soundtrack, one of 2018's absolute best, is full of startlingly loud surrounds, creating an aural blanket of world all around the viewer, too extreme to feel realistic; we're made far more aware of the environment than mere realism. And maybe the most important thing of all: this will be a slow movie. There is no hurry to this first shot. It holds on moments where nothing much happens other than perfectly unexceptional human behavior, which is turned into the stuff of amazing, transporting cinema simply through force of will and steadiness.

Eventually, the film's second shot begins, and we'll find that none of this really changes. The film is like a great dish made out of the fewest, purest ingredients: the beautiful black-and-white images, the simple camera movements that always revolve around Cleo while also taking the opportunity to watch the world around her, the omnipresent soundtrack, the long takes. Eventually, around halfway through the 135-minute running time, plot points begin to creep in, first situating Roma within the political context of 1970 in Mexico City, using the terror of the Corpus Christi massacre (in which student protesters were killed by the government, with a little help from U.S. black ops) to quietly and unfussily draw lines around Cleo's life of quiet servitude and the fundamental unfairness of her life as both a poor person and the member of an ethnic minority, presenting this one character study as symptomatic of a larger cultural collapse. Later, the film will embrace melodramatic twists and turns, but they are drawn in so unsensationally, breaking away so little from the careful stillness of the film that they feel as normal and natural as anything else (in fact, the most harrowing, melodramatic scene of the film takes place in one unmoving shot, and the horror of it comes in part because the framing and focus allow us to see more than Cleo does, and to have access to information we would definitely prefer not to have).

Throughout, it remains unflappably slow-moving, allowing events to drift by in real time. The slow cinema trend that was all over European art cinema a while back has mostly worn itself out by now, but Roma makes for a fine swan song, or revival, or whatever the case is. It's not an art movie, exactly; the director whose last film was Gravity in 2013 and whose film before that was Children of Men in 2006* is not a director whose native instincts are to move away from mainstream clarity and storytelling. That's part of what makes Roma so fascinating: it transforms one of the art film-iest of aesthetics into something simple and likable, working from the heart rather than from the head. It's still a bit daunting for the impatient, making almost no effort to step on the gas for its first hour, but just to let us start to understand Cleo, the world around her, including her put-upon employer Sofia (Marina de Tavira) and friend Adela (Nancy García García), and the generally unchanging rhythm of her life, so that the intrusions of the world and tragedy later on will hit with more weight. It's meditative and observant, calming and centering, and frankly exquisite.

It's a little bit cool, to be fair, so obsessed with depicting a place and time and watching characters move through it like fish in an aquarium that it doesn't always remember to feel things about them. We're a good step away from Y tu mamá también¸ the director's last film made in Mexico, which also tells a character story inflected with politics and class divisions, but is better at those two things and also more elaborately complicated as a work of cinema. Aparicio gives an excellent, casually lived-in performance, but the film doesn't work to foreground her the way that the earlier film hands itself off to Maribel Verdú, and Cleo remains someone we watch more than someone we feel with, sometimes. But I quibble. Roma is imperfect, but it is gorgeously, vitally imperfect, and while its mostly unchallenged haul of year-end critics' awards has come at the expense of some other pretty great movies, it's really not hard to see why something this lovely and graceful, but also this solid and thoughtful, would engender that kind of all-consuming passion.

*Who, in other words, needs to take less time to make his damn movies.

Every movie, even if just by accident, starts out by telling us how to watch it. Roma, the eighth feature film directed by Alfonso Cuarón (who also takes solo screenwriting credit), just happens to be unusually great at doing this. The film's exemplary opening shot begins as an almost completely inscrutable play of textures: a grey-on-grey diamond pattern of ceramic tiles in multiple shades overrun by shiny water. Water sounds emanating from nowhere in particular accompany the image. After a good long hold on this static composition (during which time the film's credits are all presented in a stately, Art Deco-looking font), the camera tilts up to reveal that we've been standing in a hallway whose floor is being washed by a Mixtec woman (Yalitza Aparicio) far off in the distance, at the back of a composition being shot with a just slightly wide lens to exaggerate the depth of the shot. And so gracefully that it almost doesn't register, the camera shifts to keep her centered, panning as she walks off to the left and into a house whose courtyard, it turns out, we've been standing in all along.

Virtually all of the elements we'll need to keep in mind have just been introduced to us. First, there is that woman herself, a housemaid named Cleo, inspired by the family maid of Cuarón's childhood. And there is the way Cleo is framed, a distant figure, part of the literal background; but the film requires us to notice her, as it places her in the center. It does this without pretending that it can get inside her head: it stands respectfully apart, watching her, but it does not ventriloquise her story. And let us not lose sight of the formal elements. There is the deliberate, floating quality to the camera movements, tilting and panning smoothly, guiding our attention gently but decisively (Cuarón worked as his own cinematographer, having clearly learned many wonderful from his longtime collaborator Emmanuel Lubezki). There is the crisp beauty of the black-and-white, using every delicate gradation of grey to craft something soft and dreamy, mired in a sense of the past. But at the same time, the digital sharpness of the high-resolution cameras used to shoot the film leave images so bright, clean, and solid, they feel almost uncomfortably present. The soundtrack, one of 2018's absolute best, is full of startlingly loud surrounds, creating an aural blanket of world all around the viewer, too extreme to feel realistic; we're made far more aware of the environment than mere realism. And maybe the most important thing of all: this will be a slow movie. There is no hurry to this first shot. It holds on moments where nothing much happens other than perfectly unexceptional human behavior, which is turned into the stuff of amazing, transporting cinema simply through force of will and steadiness.

Eventually, the film's second shot begins, and we'll find that none of this really changes. The film is like a great dish made out of the fewest, purest ingredients: the beautiful black-and-white images, the simple camera movements that always revolve around Cleo while also taking the opportunity to watch the world around her, the omnipresent soundtrack, the long takes. Eventually, around halfway through the 135-minute running time, plot points begin to creep in, first situating Roma within the political context of 1970 in Mexico City, using the terror of the Corpus Christi massacre (in which student protesters were killed by the government, with a little help from U.S. black ops) to quietly and unfussily draw lines around Cleo's life of quiet servitude and the fundamental unfairness of her life as both a poor person and the member of an ethnic minority, presenting this one character study as symptomatic of a larger cultural collapse. Later, the film will embrace melodramatic twists and turns, but they are drawn in so unsensationally, breaking away so little from the careful stillness of the film that they feel as normal and natural as anything else (in fact, the most harrowing, melodramatic scene of the film takes place in one unmoving shot, and the horror of it comes in part because the framing and focus allow us to see more than Cleo does, and to have access to information we would definitely prefer not to have).

Throughout, it remains unflappably slow-moving, allowing events to drift by in real time. The slow cinema trend that was all over European art cinema a while back has mostly worn itself out by now, but Roma makes for a fine swan song, or revival, or whatever the case is. It's not an art movie, exactly; the director whose last film was Gravity in 2013 and whose film before that was Children of Men in 2006* is not a director whose native instincts are to move away from mainstream clarity and storytelling. That's part of what makes Roma so fascinating: it transforms one of the art film-iest of aesthetics into something simple and likable, working from the heart rather than from the head. It's still a bit daunting for the impatient, making almost no effort to step on the gas for its first hour, but just to let us start to understand Cleo, the world around her, including her put-upon employer Sofia (Marina de Tavira) and friend Adela (Nancy García García), and the generally unchanging rhythm of her life, so that the intrusions of the world and tragedy later on will hit with more weight. It's meditative and observant, calming and centering, and frankly exquisite.

It's a little bit cool, to be fair, so obsessed with depicting a place and time and watching characters move through it like fish in an aquarium that it doesn't always remember to feel things about them. We're a good step away from Y tu mamá también¸ the director's last film made in Mexico, which also tells a character story inflected with politics and class divisions, but is better at those two things and also more elaborately complicated as a work of cinema. Aparicio gives an excellent, casually lived-in performance, but the film doesn't work to foreground her the way that the earlier film hands itself off to Maribel Verdú, and Cleo remains someone we watch more than someone we feel with, sometimes. But I quibble. Roma is imperfect, but it is gorgeously, vitally imperfect, and while its mostly unchallenged haul of year-end critics' awards has come at the expense of some other pretty great movies, it's really not hard to see why something this lovely and graceful, but also this solid and thoughtful, would engender that kind of all-consuming passion.

*Who, in other words, needs to take less time to make his damn movies.