Yukon do it

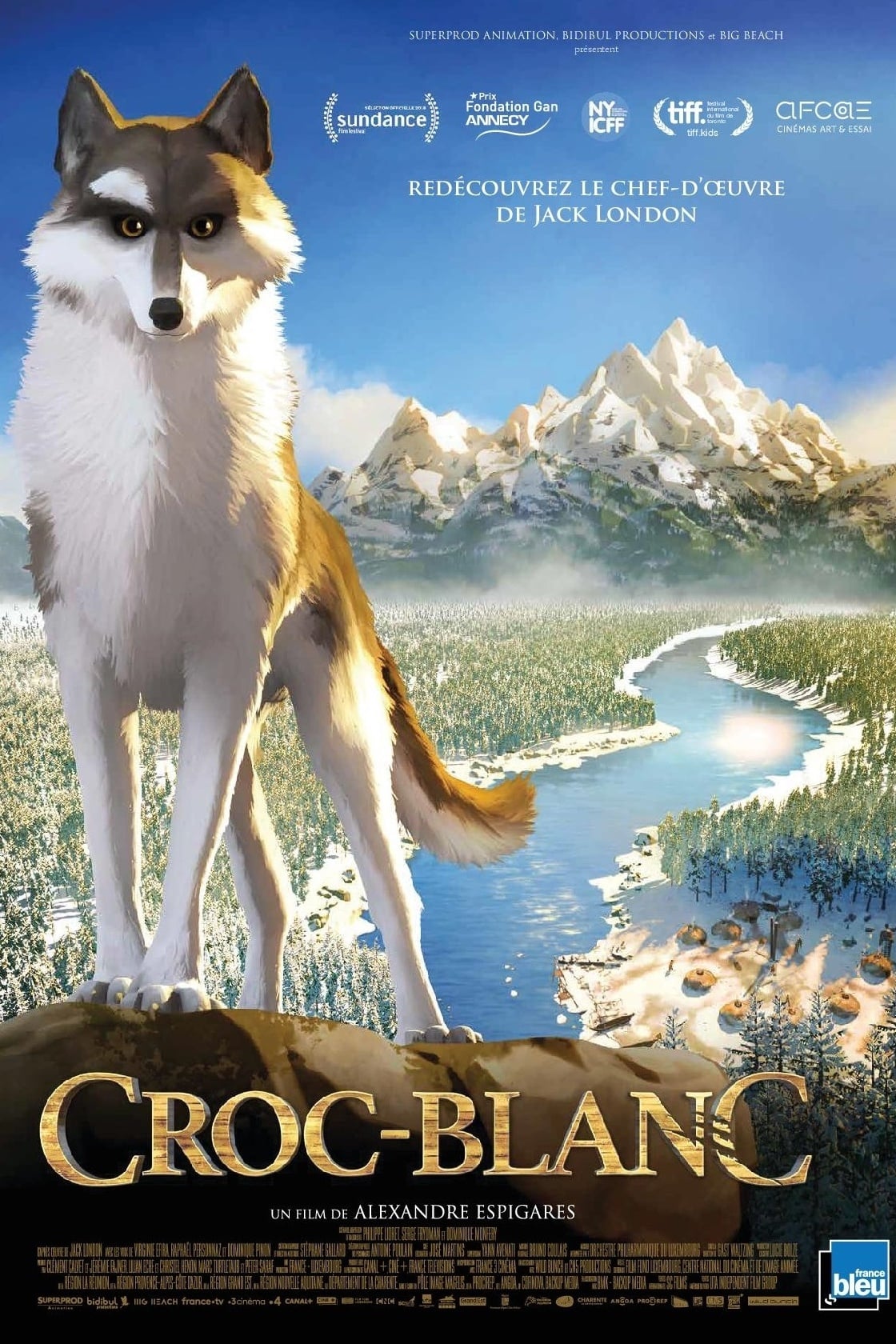

I'm not sure if Jack London's 1906 novel White Fang has remained more of a cultural touchstone in Europe than in its home country. I do know that the marketing push for the new Franco-Luxembourgian animated adaptation of the book seems to think that it's a major cultural touchstone, but who's to say. Regardless, one thing I can say with great happiness: the new White Fang is one of the most interesting attempts to do something different with the medium of computer-generated 3-D animation that has come along in a really damn long time, and that matters to me a lot more than its value as the latest screen incarnation of London's story about the travails of a feral puppy growing into doghood during the Yukon gold rush of the 1890s.

The script, adapted by Serge Frydman, Philippe Lioret, and Dominique Monfery (it is not clear to me if the film was written directly into English, or if the version being distributed in the U.S. by Netflix is an overdub of a French original), is a fast, busy affair, mostly a matter of condensing the material, ginning up some conflict, and lopping off the last part of the plot in the interest of getting through things quick as possible (the film runs a crisp 87 minutes). Which is all to say, it's a perfectly satisfactory but in no way inspired incarnation of London's story. We start in medias res, because it's 2018 and chronology is for suckers: at Fort Yukon, a greasy little trollish sort of many named Beauty Smith (Paul Giamatti) is engaged in a lucrative dogfighting ring, dominating the competition with his wolfdog White Fang. On the evening we meet them, Smith's greed has gotten the best of his concern for keeping his prize animal alive: he's agreed to pit White Fang against a pair of dogs. The ensuing carnage is kept carefully off-screen - this is a kids' movie, after all, albeit one for kids who won't immediately collapse into tears at the mere notion of dogfights - but the lighting tells us what we need to know. The brutal act is interrupted by the arrival of an ex-marshal turned gold hunter, Weedon Scott (Nick Offerman), who gets the worst of Smith's metal-plated club, the sleazy little man still sees fit to get the hell out without stopping to retrieve his dog. And then, as the insensate Scott lies draped over the insensate White Fang, we move in close to the dog, recalling the life that got him to this point.

Setting aside the annoying decision to stage this as a feature-length flashback, we've already gotten two hints of the thing that makes this White Fang successful. One of these is the transition into the flashback itself, which is staged to make sure we understand it as being subjective, and based in White Fang's sense memory of having previously been held close and safe the way he feels under Scott. The other is the way that the early part of the scene is executed from the dog's point of view: the crowds watching the fight are represented as blurry, human shaped figures, smudgy silhouettes against ice-blue lighting, with their eyes pointedly kept in swipes of blackness. And here we get to the reason why an animated White Fang is an inherently better idea idea than a live-action one: we can actually get a film that works entirely as a subjective narrative, as the book was. No editing tricks, no trained animals - the film presents its title character as a highly expressive cartoon figure, and it works terrifically well for a very long chunk of the running time. White Fang is inherently episodic: first the wolfdog wanders through the wilderness with his mother, Kiche; then he arrives at a native village where the leader Grey Beaver (Eddie Spears) recognises Kiche as his long-lost best sled dog; then Smith extorts him from Grey Beaver; then he comes to live at the homestead of Scott and his steel-willed wife Maggie (Rashida Jones). The film gets progressively worse as it goes along, unfortunately, but that very long opening sequence, when it's wordless and centered around the wild dogs in an untouched, inhuman environment, is excellent.

A lot of this has to do with the film's animation and design, for that's the not-very-hidden secret: while this is an adequate at best version of White Fang, it's a stellar exercise in animation. This is not, let us keep in mind, a big American studio picture, and it lacks the budget that allows for the extremely sophisticated rigging, texturing, and lighting of the most polished CGI animation. So it doesn't try for those things. Instead, the film's big gambit is to make a virtue of its limitations, particularly in the texture of its animals and backgrounds. The film looks like an oil painting: this is most vividly seen in the dogs' coats, which look nothing at all like fur (they're flat and rigid), but do look like a painting of fur, with beautiful feathering from white to grey and red. The same thing is true of the backgrounds, which present the array of Yukon vistas across the seasons as slightly fuzzy patches of colors rather than photorealistic landscapes.

The results are stupidly beautiful. Making a CG animated film that doesn't look like CG has been in the air since at least the early pre-production on Tangled, though it's not something anyone has really followed through with in a sustained way. I don't expect White Fang to open the floodgates of 3-D animation that looks like oil paintings in depth (though I can dream), but as a one-off experiment, it's superb. And besides which, it fits the material: the film's sentimental approach to Realist landscapes is very much in keeping with the the sort of art being produced in America in the last couple of decades of the 19th Century.

This is all true with a gigantic caveat: the film completely falls down when it comes to representing human beings. There are two reasons for this: one is that the humans have also been drawn with rigid surfaces, and unlike wild dogs, we're used to looking at humans, so that as they move around, but their hair and skin remain stony and locked in place, it's quietly disturbing. Or, in the case of Beauty Smith, actively repulsive. The other thing is that, while the dogs have all been animated, the humans have mostly been motion-captured. This means that the scenes of White Fang leaping through space and interacting with his environment were built from the ground up to fill the peculiarities of animated movement, while the humans feel a little jittery, like everybody in the cast did shots of espresso right before the cameras rolled.

Still, the film is dog-oriented, so the regrettable humans end up being a much smaller problem than you might imagine. Plus, at least Offerman and Jones are providing such subdued, pleasant vocal performances that it somewhat compensates for the plastic zombies they're inhabiting. It still leaves plenty of space for White Fang to look amazing for most of its running time. That plus a story that's routine but never bad, and we have here a rather remarkable piece of work, a film that has figured out exactly the place it can afford to occupy in the animation ecosystem and tailored itself perfectly to fill that space. It's so good that it actually makes me sad that it's going to be tarnished with the increasingly dubious Netflix brand name - you can tell it was made on a budget, but this absolutely could compete in a more demanding marketplace than the "shit for kids on streaming" ghetto it's landed in.

The script, adapted by Serge Frydman, Philippe Lioret, and Dominique Monfery (it is not clear to me if the film was written directly into English, or if the version being distributed in the U.S. by Netflix is an overdub of a French original), is a fast, busy affair, mostly a matter of condensing the material, ginning up some conflict, and lopping off the last part of the plot in the interest of getting through things quick as possible (the film runs a crisp 87 minutes). Which is all to say, it's a perfectly satisfactory but in no way inspired incarnation of London's story. We start in medias res, because it's 2018 and chronology is for suckers: at Fort Yukon, a greasy little trollish sort of many named Beauty Smith (Paul Giamatti) is engaged in a lucrative dogfighting ring, dominating the competition with his wolfdog White Fang. On the evening we meet them, Smith's greed has gotten the best of his concern for keeping his prize animal alive: he's agreed to pit White Fang against a pair of dogs. The ensuing carnage is kept carefully off-screen - this is a kids' movie, after all, albeit one for kids who won't immediately collapse into tears at the mere notion of dogfights - but the lighting tells us what we need to know. The brutal act is interrupted by the arrival of an ex-marshal turned gold hunter, Weedon Scott (Nick Offerman), who gets the worst of Smith's metal-plated club, the sleazy little man still sees fit to get the hell out without stopping to retrieve his dog. And then, as the insensate Scott lies draped over the insensate White Fang, we move in close to the dog, recalling the life that got him to this point.

Setting aside the annoying decision to stage this as a feature-length flashback, we've already gotten two hints of the thing that makes this White Fang successful. One of these is the transition into the flashback itself, which is staged to make sure we understand it as being subjective, and based in White Fang's sense memory of having previously been held close and safe the way he feels under Scott. The other is the way that the early part of the scene is executed from the dog's point of view: the crowds watching the fight are represented as blurry, human shaped figures, smudgy silhouettes against ice-blue lighting, with their eyes pointedly kept in swipes of blackness. And here we get to the reason why an animated White Fang is an inherently better idea idea than a live-action one: we can actually get a film that works entirely as a subjective narrative, as the book was. No editing tricks, no trained animals - the film presents its title character as a highly expressive cartoon figure, and it works terrifically well for a very long chunk of the running time. White Fang is inherently episodic: first the wolfdog wanders through the wilderness with his mother, Kiche; then he arrives at a native village where the leader Grey Beaver (Eddie Spears) recognises Kiche as his long-lost best sled dog; then Smith extorts him from Grey Beaver; then he comes to live at the homestead of Scott and his steel-willed wife Maggie (Rashida Jones). The film gets progressively worse as it goes along, unfortunately, but that very long opening sequence, when it's wordless and centered around the wild dogs in an untouched, inhuman environment, is excellent.

A lot of this has to do with the film's animation and design, for that's the not-very-hidden secret: while this is an adequate at best version of White Fang, it's a stellar exercise in animation. This is not, let us keep in mind, a big American studio picture, and it lacks the budget that allows for the extremely sophisticated rigging, texturing, and lighting of the most polished CGI animation. So it doesn't try for those things. Instead, the film's big gambit is to make a virtue of its limitations, particularly in the texture of its animals and backgrounds. The film looks like an oil painting: this is most vividly seen in the dogs' coats, which look nothing at all like fur (they're flat and rigid), but do look like a painting of fur, with beautiful feathering from white to grey and red. The same thing is true of the backgrounds, which present the array of Yukon vistas across the seasons as slightly fuzzy patches of colors rather than photorealistic landscapes.

The results are stupidly beautiful. Making a CG animated film that doesn't look like CG has been in the air since at least the early pre-production on Tangled, though it's not something anyone has really followed through with in a sustained way. I don't expect White Fang to open the floodgates of 3-D animation that looks like oil paintings in depth (though I can dream), but as a one-off experiment, it's superb. And besides which, it fits the material: the film's sentimental approach to Realist landscapes is very much in keeping with the the sort of art being produced in America in the last couple of decades of the 19th Century.

This is all true with a gigantic caveat: the film completely falls down when it comes to representing human beings. There are two reasons for this: one is that the humans have also been drawn with rigid surfaces, and unlike wild dogs, we're used to looking at humans, so that as they move around, but their hair and skin remain stony and locked in place, it's quietly disturbing. Or, in the case of Beauty Smith, actively repulsive. The other thing is that, while the dogs have all been animated, the humans have mostly been motion-captured. This means that the scenes of White Fang leaping through space and interacting with his environment were built from the ground up to fill the peculiarities of animated movement, while the humans feel a little jittery, like everybody in the cast did shots of espresso right before the cameras rolled.

Still, the film is dog-oriented, so the regrettable humans end up being a much smaller problem than you might imagine. Plus, at least Offerman and Jones are providing such subdued, pleasant vocal performances that it somewhat compensates for the plastic zombies they're inhabiting. It still leaves plenty of space for White Fang to look amazing for most of its running time. That plus a story that's routine but never bad, and we have here a rather remarkable piece of work, a film that has figured out exactly the place it can afford to occupy in the animation ecosystem and tailored itself perfectly to fill that space. It's so good that it actually makes me sad that it's going to be tarnished with the increasingly dubious Netflix brand name - you can tell it was made on a budget, but this absolutely could compete in a more demanding marketplace than the "shit for kids on streaming" ghetto it's landed in.