Birds of a feather

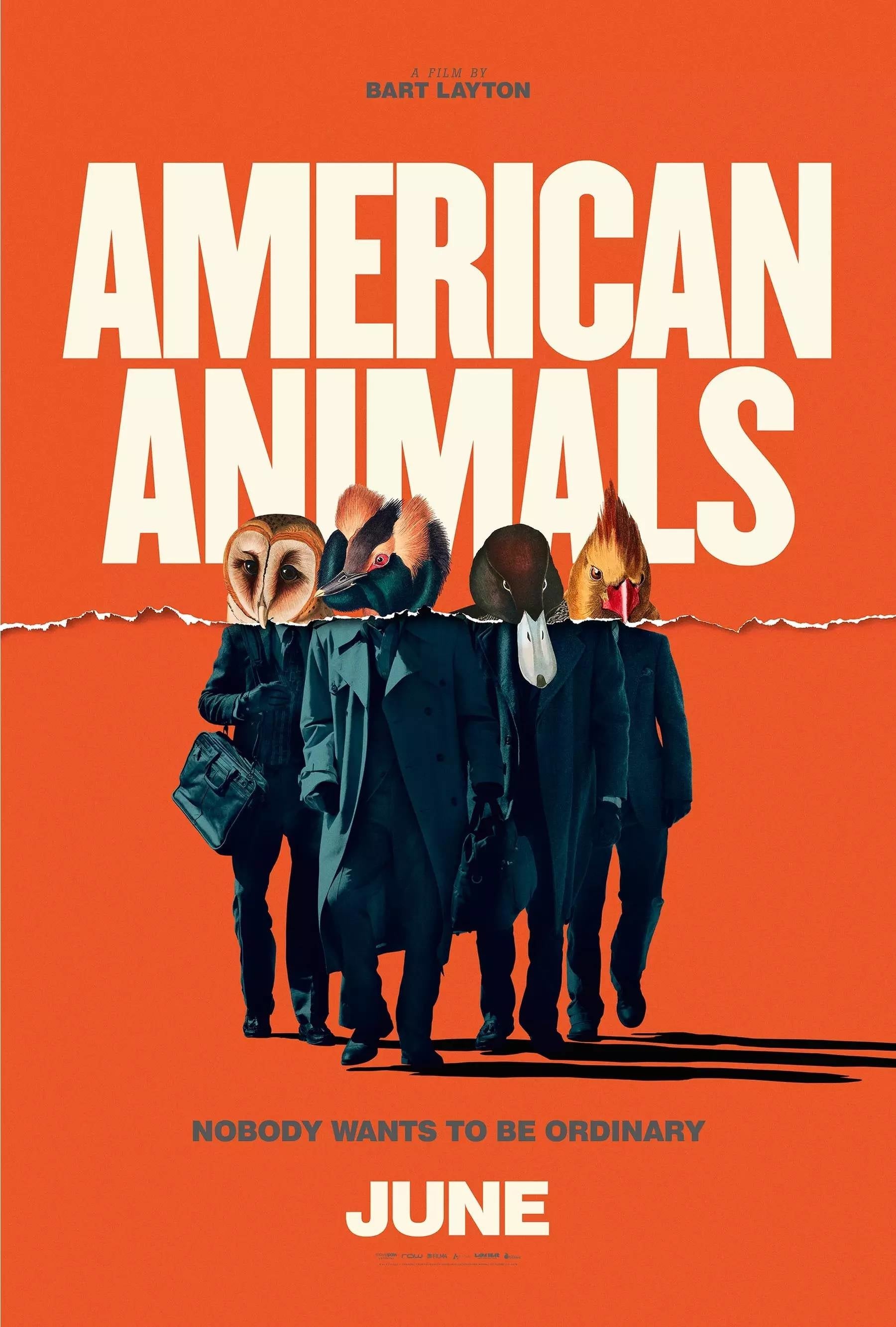

American Animals is a very good movie that frankly doesn't seem to understand why it's very good. This is apparent right from the very start - or rather, it becomes retroactively apparent that the very start is all mixed up. First, there's a quote from Darwin, talking about "American animals" colonising cave systems in Kentucky through successive generations, and then there are close-ups of violent acts being perpetrated by birds upon terrified rodents from the groundbreaking paintings of John James Audubon. One immediately gets the notion that this is setting up a study of nihilistic, sociopathic savagery, and that's not really what the film ends up being about at all. I mean, it could be, but in practice it's much goofier and then much sadder, and it looks upon its sociopaths as tragedies, not monsters. At any rate, it's an opening that in no way prepare one for the movie to come, and so I wonder: did the filmmakers just not know what movie they'd made? Stranger things have happened.

The film is the true story of a group of four college students, who in 2003 and 2004 attempted to steal $12 million in rare books from the library of Transylvania University in Kentucky. We know that they failed because we get to meet them, in the flesh, talking candidly about their crimes in a way that surely would not happen if they had gotten away with it. So the film is a part documentary, part narrative recreation that is much too artful and much too long to possibly justify the term "documentary re-enactment". It's a neat little formal hybrid, one that isn't entirely the most original thing out there - this summer marks the 30th anniversary of The Thin Blue Line, a film that got itself celebrated and score for doing the same thing - but it's damned effective in the way it moves between talking heads interviews with Spencer Reinhard, Warren Lipka, Eric Borsuk, and Charles "Chas" Allen II, and dramatic scenes with those four men being played respectively by Barry Keoghan, Evan Peters, Jared Abrahamson, and Blake Jenner. Sometimes it repeats the story immediately after they tell it, sometimes it cuts into the "fiction" version right in the middle of a sentence, sometimes it shows the dramatic version and then follows with one of the interview subjects disagreeing with what they just saw.

It's pretty obvious territory for a film to mine: turns out that people remember things differently, and those differences will tend to break out in ways that are most flattering to the individual doing the remembering. Incidentally, this is another point at which American Animals misunderstands itself: after the credits, it portentously displays the text "THIS IS NOT BASED ON A TRUE STORY", with the middle words disappearing to leave "THIS IS A TRUE STORY", and of course the whole argument the film is making is, aye, but which true story, and that filmmaking - even documentary filmmaking - is necessarily choosing a version of events that probably didn't happen just the way the filmmaker says it did. And there's no hint that the words are meant to be ironic.

At any rate, though it's mostly doing the expected thing, American Animals does it with great energy: you can almost feel the joy of editors Nick Fenton, Chris Gill, and Julian Hart pulsing out of the screen. Plus, the film itself is quite a remarkable balancing act of tone and pacing. The basic version of the story goes that Spencer and Warren hit upon the idea of the stealing the books, primarily an ultra-rare edition of Audubon's The Birds of America, largely as a way of staving off boredom - Spencer wants to be a painter but lacks what he perceives to be the requisite passion and spark, Warren has been pressed into playing college sports and hates it very much - but it quickly turns into an all-consuming obsession. Doing research in the form of watching a lot of caper films, the two (and later their co-conspirators) work up quite an elaborate plan and then put it into practice, where it of course terribly wrong, involving an act of violence than none of the boys are prepared for, and yet it happens anyway.

There's nothing all that new here, either: turns out that movies aren't a guide to life, young people hungry for Meaning and Greatness in their lives have confused petty narcissism for philosophy, one's right to play-act fantasies absolutely does not extend to the moment that other people end up weeping in terror on the floor, et cetera. What makes American Animals work so well is, in part, the astonishing turns in mood: it's a flat-out comedy for much of its running time, happily poking fun at the hapless kids but finding the way their enthusiasm takes over their good sense to be sloppily endearing, and the way that the grown-up real-life men still have echoes of that enthusiasm, now mixed with distinct ruefulness and shame, gives the film a good deal of upbeat energy. The twist comes when things go wrong, and a human cost is extracted, and just like that, American Animals stops being any fun at all. It's a remarkably deft tonal shift that director Bart Layton covers with extreme fluidity: it's not that we don't notice the shift, because we do, but the noticing itself becomes a productive part of the film's effect (Layton did similar work in his only previous feature project, the excellent 2012 documentary The Imposter). It's basically trying to put the audience through the same mental process as the characters: moving from a larking, adolescent "isn't this fun?" to the horrifyingly sudden discovery that "holy fucking shit, this isn't fun at all".

Again, there's no real freshness to this: in keeping with most films that are titled "American _____", American Animals is regurgitating more than it invents. Though as diagnoses of the problem of young idle men who think they're entitled to more than they are, it at least has the benefit of never, ever feeling like a polemic. Anyway, the film has a much bigger problem: it gives up on the documentary/re-enactment gimmick around halfway through, turning into a straightforward biography that watches the increasingly convoluted heist play itself out, occasionally with a shot of one of the adult men looking sad and regretful. And it's not that this is bad: in fact, American Animals is still quite a good heist movie in and of itself, with a terrific cast (Keoghan's nervously passive reactions, letting himself go along with the thing becasue he's too uncertain of himself to back out, is very good; Peters's fine delineation between Warren's breezy braggadocio with the very serious self-justification of a young left-anarchist, and the panicky confusion and self-hatred he hides below that braggadocio, is superb), an a plot that's just the right amount of complicated and just the right amount of admirably idiotic. The thing is, American Animals spends its first hour having a field day playing with form and making meta-jokes about the basic untrustworthiness of "non-fiction" cinema; the recognition that a much broader, bolder, and more intellectually stimulating movie has been taken away from us actively hinders what would, in its own right, still be a very fine movie otherwise.

The film is the true story of a group of four college students, who in 2003 and 2004 attempted to steal $12 million in rare books from the library of Transylvania University in Kentucky. We know that they failed because we get to meet them, in the flesh, talking candidly about their crimes in a way that surely would not happen if they had gotten away with it. So the film is a part documentary, part narrative recreation that is much too artful and much too long to possibly justify the term "documentary re-enactment". It's a neat little formal hybrid, one that isn't entirely the most original thing out there - this summer marks the 30th anniversary of The Thin Blue Line, a film that got itself celebrated and score for doing the same thing - but it's damned effective in the way it moves between talking heads interviews with Spencer Reinhard, Warren Lipka, Eric Borsuk, and Charles "Chas" Allen II, and dramatic scenes with those four men being played respectively by Barry Keoghan, Evan Peters, Jared Abrahamson, and Blake Jenner. Sometimes it repeats the story immediately after they tell it, sometimes it cuts into the "fiction" version right in the middle of a sentence, sometimes it shows the dramatic version and then follows with one of the interview subjects disagreeing with what they just saw.

It's pretty obvious territory for a film to mine: turns out that people remember things differently, and those differences will tend to break out in ways that are most flattering to the individual doing the remembering. Incidentally, this is another point at which American Animals misunderstands itself: after the credits, it portentously displays the text "THIS IS NOT BASED ON A TRUE STORY", with the middle words disappearing to leave "THIS IS A TRUE STORY", and of course the whole argument the film is making is, aye, but which true story, and that filmmaking - even documentary filmmaking - is necessarily choosing a version of events that probably didn't happen just the way the filmmaker says it did. And there's no hint that the words are meant to be ironic.

At any rate, though it's mostly doing the expected thing, American Animals does it with great energy: you can almost feel the joy of editors Nick Fenton, Chris Gill, and Julian Hart pulsing out of the screen. Plus, the film itself is quite a remarkable balancing act of tone and pacing. The basic version of the story goes that Spencer and Warren hit upon the idea of the stealing the books, primarily an ultra-rare edition of Audubon's The Birds of America, largely as a way of staving off boredom - Spencer wants to be a painter but lacks what he perceives to be the requisite passion and spark, Warren has been pressed into playing college sports and hates it very much - but it quickly turns into an all-consuming obsession. Doing research in the form of watching a lot of caper films, the two (and later their co-conspirators) work up quite an elaborate plan and then put it into practice, where it of course terribly wrong, involving an act of violence than none of the boys are prepared for, and yet it happens anyway.

There's nothing all that new here, either: turns out that movies aren't a guide to life, young people hungry for Meaning and Greatness in their lives have confused petty narcissism for philosophy, one's right to play-act fantasies absolutely does not extend to the moment that other people end up weeping in terror on the floor, et cetera. What makes American Animals work so well is, in part, the astonishing turns in mood: it's a flat-out comedy for much of its running time, happily poking fun at the hapless kids but finding the way their enthusiasm takes over their good sense to be sloppily endearing, and the way that the grown-up real-life men still have echoes of that enthusiasm, now mixed with distinct ruefulness and shame, gives the film a good deal of upbeat energy. The twist comes when things go wrong, and a human cost is extracted, and just like that, American Animals stops being any fun at all. It's a remarkably deft tonal shift that director Bart Layton covers with extreme fluidity: it's not that we don't notice the shift, because we do, but the noticing itself becomes a productive part of the film's effect (Layton did similar work in his only previous feature project, the excellent 2012 documentary The Imposter). It's basically trying to put the audience through the same mental process as the characters: moving from a larking, adolescent "isn't this fun?" to the horrifyingly sudden discovery that "holy fucking shit, this isn't fun at all".

Again, there's no real freshness to this: in keeping with most films that are titled "American _____", American Animals is regurgitating more than it invents. Though as diagnoses of the problem of young idle men who think they're entitled to more than they are, it at least has the benefit of never, ever feeling like a polemic. Anyway, the film has a much bigger problem: it gives up on the documentary/re-enactment gimmick around halfway through, turning into a straightforward biography that watches the increasingly convoluted heist play itself out, occasionally with a shot of one of the adult men looking sad and regretful. And it's not that this is bad: in fact, American Animals is still quite a good heist movie in and of itself, with a terrific cast (Keoghan's nervously passive reactions, letting himself go along with the thing becasue he's too uncertain of himself to back out, is very good; Peters's fine delineation between Warren's breezy braggadocio with the very serious self-justification of a young left-anarchist, and the panicky confusion and self-hatred he hides below that braggadocio, is superb), an a plot that's just the right amount of complicated and just the right amount of admirably idiotic. The thing is, American Animals spends its first hour having a field day playing with form and making meta-jokes about the basic untrustworthiness of "non-fiction" cinema; the recognition that a much broader, bolder, and more intellectually stimulating movie has been taken away from us actively hinders what would, in its own right, still be a very fine movie otherwise.

Categories: caper films, comedies, crime pictures, documentaries