Some mad bugger's wall

A review requested by Michael Matula, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Pink Floyd's 1979 double album The Wall was accompanied by one of the most ridiculously complex tour concepts in rock history. As envisioned by frontmant Roger Waters, the performance was to be accompanied by elaborate lighting effects, puppetry, and the construction, onstage of a brick wall between the band and the audience, making concrete Waters's metaphor of the separation between the art-maker and the art-consumer in an alienated world. It was less a rock concert than a full Broadway-style theatrical production, so unreasonable to move around and so costly to stage that it was ultimately only performed in four venues over a total of 31 performances. One cannot call it a boondoggle, since it was by most accounts a thrilling spectacle; one, however, call it an impossibly ambitious pipe dream that could only have possibly made sense for a few months in Waters's passionate, overheated brain.

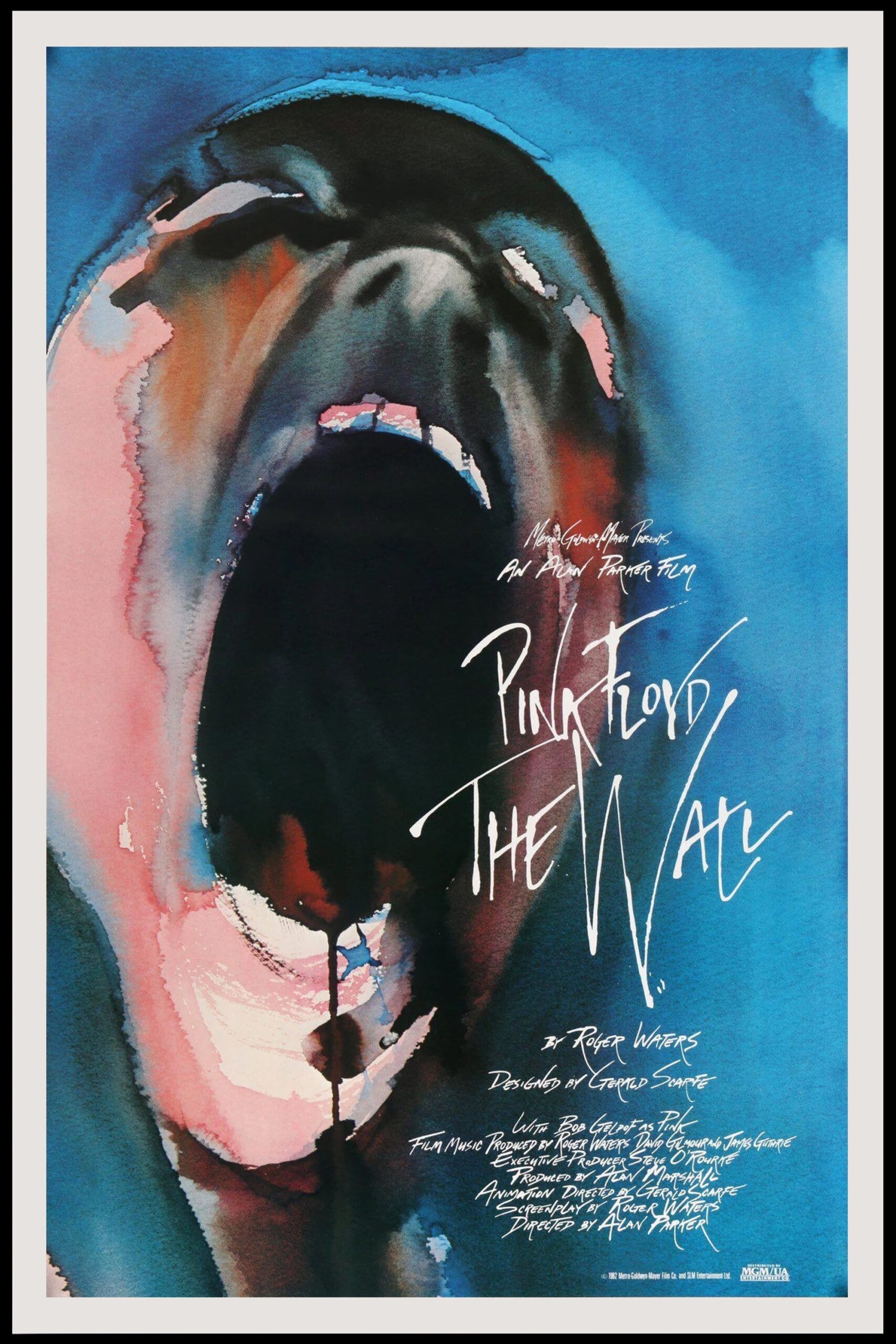

It's altogether possible that this ludicrous staging idea still isn't the most wild flight of fancy associated with the album. As evidence, I am please to give you Pink Floyd: The Wall, the 1982 feature film written and conceived by Waters as the cinematic incarnation of many of the ideas from the album and concert, and then dialed up a few notches from that. It is a film of visionary madness: a 90-minute music video that expands on the album's themes with some of the most shocking, even terrifying imagery in the history of British cinema. It's the child of at least three man, all of whom found the process miserable and exhausting: Waters, director Alan Parker, and animation director Gerald Scarfe, a political cartoonist who oversaw the creation of some 12 or 15 minutes' worth of animated sequences across the film's running time. And I think we might safely add to that list star Bob Geldof (also miserable and exhausted by the end), at the time the lead singer of the Irish punk group the Boomtown Rats, whose presence in what barely amounts to a role at all discernibly nudges the project in a more feverish direction than I think could possibly have been the case if Waters had played the role, as was his original intent.

Pink Floyd: The Wall follows The Wall quite closely, adding one song and removing two (including "Hey You", one of the album's more famous tracks), and in some way altering about two-thirds of the remaining songs, while using many of the same recordings (some remixed). In both cases, the story is about Pink (Geldof), whose father died in the Second World War and whose mother grew overly-protective as a result. As Pink grows to adulthood, having at no point had any support in his personal growth from his family or the institutions of English society, he finds himself so incapable of making emotional connections with other humans that there might as well be a wall between him and the world. He finds some success as a rock star, trying desperately to communicate with his poetry, but his message is completely lost in a haze of groupies and drugs, and he ends up losing his mind and lead a neo-Nazi rally for his adoring fanbase. That ol' chestnut.

This is all about as subtle as having a dumptruck full of bricks fall on your head, and nobody involved in the film's production seems to have been at all motivated to make it subtler. The sequence set to the massive hit song "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" climaxes with schoolchildren on a dull grey assembly line having their faces turned into impersonal, screaming masks, right before they fall into a meat grinder operated by the headmaster. If one cannot at least guess at what Waters and Parker might have had in mind with this little bit of symbolism, one would be well-advised to get out of the business of decoding symbolism altogether.

But for all that it's obvious, it's also damned effective. Honestly, it might even be too effective. The film is 95 straight minutes of some enormously bleak, cynical social commentary and psychological study. Some of this is inherited directly from the album, whose swooning orchestrations tend towards the dark and forbidding, even in the most "beautiful" songs (which I'd suggest are the bitter "Mother", completely redone for the film, and the hallucinatory "Comfortably Numb", only slightly retouched): the very sound of The Wall is heaving and wearing. The movie includes every bit of that, and doubles-down on it with visuals that peak at "gloomy" and routinely go much darker than that. The film is by far the strangest entry in Parker's career: most of his work (14 features and two telefilms) has a subdued low-key realism, shot in authentic spaces and with normal people (the best example is his second music-driven feature, 1991's The Commitments).

This is, in fact, true of large portions of Pink Floyd: The Wall as well: much of the film showcases Pink's memories of his childhood (when he's played by Kevin McKeon and David Bingham), shot in a perfectly stripped-down manner by Parker and cinematographer Peter Biziou, relying on a grainy brown palette. There's a basic narrative reason for this: the aesthetic of these childhood scenes has a "normal" quality that signifies the character's hopeless nostalgia. But it also provides a jarring contrast for the more baroque look of the heavily symbolic moments, like that assembly line of brainwashed kids, or the extreme stylisation of Pink's life as an out-of-control rock star. For example, an orgy with groupies during the song "Young Lust" is full of canted angles and ugly slashes of light that look not realistic in the slightest, though they have the same filmy look of the grainy brown footage. The orgy is already one of the most unpleasant moments in a movie full of unpleasant moments, helped out by the snarling vocal track; the messy chaos of the lighting and camerawork, and the way that the human beings onscreen are turned into animal shapes moving with no continuity pushes it higher.

And then there are the moments where the film directly connects these two moods: "Comfortably Numb" is the obvious example, with the dreamy choruses representing Pink's inner monologue taking place in casually natural shots that wouldn't feel out of place in a Ken Loach film, while the droning verses ventriloquising Pink's doctor and manager (the latter played, with all due sweaty sleaziness, by Bob Hoskins) are shaky and uncomfortably close and sloppy. The contrast heightens the emotional intensity of what was already one of the album's most directly emotional songs, making it almost unbearable in flashes.

It is, I think, exactly Parker's simple style that gives Pink Floyd: The Wall much of its power. The most obvious point of comparison* is the other film based on a major '70s concept album from a British rock group, the 1975 film of The Who's Tommy, directed by the florid visual pyrotechnician Ken Russell. I love that film without apology, but the difference between Russell's approach and Parker's is instructive: with Russell, everything is already cranked up all the way, all the time, in a stylish orgasm of wild surrealism. It's an amazing spectacle but it arguably stays there. Pink Floyd: The Wall, by frequently returning to middlebrow visual cues of normal domestic life, gets much more punch out of its more extreme visual and narrative gestures, and remains constantly devastating where Tommy is merely overwhelming.

Parker's reliance on kitchen sink realism as a baseline also means that Scarfe's animation makes more of a contrast as well. And this is where the film goes all the way dark. Scarfe has a political cartoonist's sense of literalism: Pink's mother is a flower that looks conspicuously like a vulva, and late in the film she consumes the scared Pink as he regresses to childhood, for example. Still, a bit of literalism and dimestore Freudianism can be forgiven in light of how well the animation fits in with the flow of the story and the pounding music. Scarfe's main approach involves constant, fluid motion and morphing, with every sapient being and many of the inanimate objects proving to be freakishly unstable, as an early indication of Pink's internal discord. It is truly nightmarish stuff, undefinable but always queasily suggestive of other things, mostly involving death, decay, and the grossest aspects of human sex, it's executed in a strictly limited range of muted colors, and it's just far enough from matching the music that it never feels "right"; it exists as some kind of aberration.

The animation starts drawing on Nazi imagery long before the live-action footage does at well, which makes it all more imposing. The album The Wall touches on Fascism, but mostly it's about Waters's feeling of disconnection and his inability to communicate. The film Pink Floyd: The Wall is about that, and it's also obsessed with the War - Pink's dead war hero father hangs over the imagery, one of the single most striking things that happens is the British flag transforming into a blood-streaked cross in a military cemetery, and Fascist iconography is everywhere. As much as it's about the frustrations of celebrity or the anomie of modern life, Pink Floyd: The Wall is about the attractive pull of Fascist regimes to the conservative English soul; Pink's transformation into a neo-Nazi ideologue is less of a sign that he's been broken and split, than the inevitable expression of something that has been building throughout the movie, and Geldof is just terrifying in his savage facial expressions.

This all adds up to one of the more exceptional, unprecedented films to ever come from Great Britain, a guttural howl of rage at the darkest aspects of English culture from school to adulthood to the ease with which the nascent punk scene became a breeding ground for a very English form of neo-Nazism. Even without that, the film's depiction of Pink's wallowing in his own hedonism and self-hatred, and the grim potency of the animation are enough to make this a pretty heavy, dark experience. And here I go back to my little aside: maybe it's too effective. Let us not mince words: I love this film. But I don't make a habit of re-watching it. It's a raging, angry, hopeless movie - it doesn't exactly replicate the album's "all this will happen again and again" gesture, but it comes close to implying it - and everything about it that works works in the direction of making it as dark as possible. Still, nothing this potent can be discarded out of hand, and I'll happily call this a great piece of filmmaking. In fact, if I may commit a great heresy: while I'll never come close to watching the movie as often as I've listened to the album, I think the movie might actually be the superior embodiment of Waters's apocalyptic vision.

*Or at least the second-most obvious. The most obvious is maybe Parker's later adaptation of a '70s concept album, the 1996 film of Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim Rice's Evita, but it hardly seems sporting to bring that up.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Pink Floyd's 1979 double album The Wall was accompanied by one of the most ridiculously complex tour concepts in rock history. As envisioned by frontmant Roger Waters, the performance was to be accompanied by elaborate lighting effects, puppetry, and the construction, onstage of a brick wall between the band and the audience, making concrete Waters's metaphor of the separation between the art-maker and the art-consumer in an alienated world. It was less a rock concert than a full Broadway-style theatrical production, so unreasonable to move around and so costly to stage that it was ultimately only performed in four venues over a total of 31 performances. One cannot call it a boondoggle, since it was by most accounts a thrilling spectacle; one, however, call it an impossibly ambitious pipe dream that could only have possibly made sense for a few months in Waters's passionate, overheated brain.

It's altogether possible that this ludicrous staging idea still isn't the most wild flight of fancy associated with the album. As evidence, I am please to give you Pink Floyd: The Wall, the 1982 feature film written and conceived by Waters as the cinematic incarnation of many of the ideas from the album and concert, and then dialed up a few notches from that. It is a film of visionary madness: a 90-minute music video that expands on the album's themes with some of the most shocking, even terrifying imagery in the history of British cinema. It's the child of at least three man, all of whom found the process miserable and exhausting: Waters, director Alan Parker, and animation director Gerald Scarfe, a political cartoonist who oversaw the creation of some 12 or 15 minutes' worth of animated sequences across the film's running time. And I think we might safely add to that list star Bob Geldof (also miserable and exhausted by the end), at the time the lead singer of the Irish punk group the Boomtown Rats, whose presence in what barely amounts to a role at all discernibly nudges the project in a more feverish direction than I think could possibly have been the case if Waters had played the role, as was his original intent.

Pink Floyd: The Wall follows The Wall quite closely, adding one song and removing two (including "Hey You", one of the album's more famous tracks), and in some way altering about two-thirds of the remaining songs, while using many of the same recordings (some remixed). In both cases, the story is about Pink (Geldof), whose father died in the Second World War and whose mother grew overly-protective as a result. As Pink grows to adulthood, having at no point had any support in his personal growth from his family or the institutions of English society, he finds himself so incapable of making emotional connections with other humans that there might as well be a wall between him and the world. He finds some success as a rock star, trying desperately to communicate with his poetry, but his message is completely lost in a haze of groupies and drugs, and he ends up losing his mind and lead a neo-Nazi rally for his adoring fanbase. That ol' chestnut.

This is all about as subtle as having a dumptruck full of bricks fall on your head, and nobody involved in the film's production seems to have been at all motivated to make it subtler. The sequence set to the massive hit song "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" climaxes with schoolchildren on a dull grey assembly line having their faces turned into impersonal, screaming masks, right before they fall into a meat grinder operated by the headmaster. If one cannot at least guess at what Waters and Parker might have had in mind with this little bit of symbolism, one would be well-advised to get out of the business of decoding symbolism altogether.

But for all that it's obvious, it's also damned effective. Honestly, it might even be too effective. The film is 95 straight minutes of some enormously bleak, cynical social commentary and psychological study. Some of this is inherited directly from the album, whose swooning orchestrations tend towards the dark and forbidding, even in the most "beautiful" songs (which I'd suggest are the bitter "Mother", completely redone for the film, and the hallucinatory "Comfortably Numb", only slightly retouched): the very sound of The Wall is heaving and wearing. The movie includes every bit of that, and doubles-down on it with visuals that peak at "gloomy" and routinely go much darker than that. The film is by far the strangest entry in Parker's career: most of his work (14 features and two telefilms) has a subdued low-key realism, shot in authentic spaces and with normal people (the best example is his second music-driven feature, 1991's The Commitments).

This is, in fact, true of large portions of Pink Floyd: The Wall as well: much of the film showcases Pink's memories of his childhood (when he's played by Kevin McKeon and David Bingham), shot in a perfectly stripped-down manner by Parker and cinematographer Peter Biziou, relying on a grainy brown palette. There's a basic narrative reason for this: the aesthetic of these childhood scenes has a "normal" quality that signifies the character's hopeless nostalgia. But it also provides a jarring contrast for the more baroque look of the heavily symbolic moments, like that assembly line of brainwashed kids, or the extreme stylisation of Pink's life as an out-of-control rock star. For example, an orgy with groupies during the song "Young Lust" is full of canted angles and ugly slashes of light that look not realistic in the slightest, though they have the same filmy look of the grainy brown footage. The orgy is already one of the most unpleasant moments in a movie full of unpleasant moments, helped out by the snarling vocal track; the messy chaos of the lighting and camerawork, and the way that the human beings onscreen are turned into animal shapes moving with no continuity pushes it higher.

And then there are the moments where the film directly connects these two moods: "Comfortably Numb" is the obvious example, with the dreamy choruses representing Pink's inner monologue taking place in casually natural shots that wouldn't feel out of place in a Ken Loach film, while the droning verses ventriloquising Pink's doctor and manager (the latter played, with all due sweaty sleaziness, by Bob Hoskins) are shaky and uncomfortably close and sloppy. The contrast heightens the emotional intensity of what was already one of the album's most directly emotional songs, making it almost unbearable in flashes.

It is, I think, exactly Parker's simple style that gives Pink Floyd: The Wall much of its power. The most obvious point of comparison* is the other film based on a major '70s concept album from a British rock group, the 1975 film of The Who's Tommy, directed by the florid visual pyrotechnician Ken Russell. I love that film without apology, but the difference between Russell's approach and Parker's is instructive: with Russell, everything is already cranked up all the way, all the time, in a stylish orgasm of wild surrealism. It's an amazing spectacle but it arguably stays there. Pink Floyd: The Wall, by frequently returning to middlebrow visual cues of normal domestic life, gets much more punch out of its more extreme visual and narrative gestures, and remains constantly devastating where Tommy is merely overwhelming.

Parker's reliance on kitchen sink realism as a baseline also means that Scarfe's animation makes more of a contrast as well. And this is where the film goes all the way dark. Scarfe has a political cartoonist's sense of literalism: Pink's mother is a flower that looks conspicuously like a vulva, and late in the film she consumes the scared Pink as he regresses to childhood, for example. Still, a bit of literalism and dimestore Freudianism can be forgiven in light of how well the animation fits in with the flow of the story and the pounding music. Scarfe's main approach involves constant, fluid motion and morphing, with every sapient being and many of the inanimate objects proving to be freakishly unstable, as an early indication of Pink's internal discord. It is truly nightmarish stuff, undefinable but always queasily suggestive of other things, mostly involving death, decay, and the grossest aspects of human sex, it's executed in a strictly limited range of muted colors, and it's just far enough from matching the music that it never feels "right"; it exists as some kind of aberration.

The animation starts drawing on Nazi imagery long before the live-action footage does at well, which makes it all more imposing. The album The Wall touches on Fascism, but mostly it's about Waters's feeling of disconnection and his inability to communicate. The film Pink Floyd: The Wall is about that, and it's also obsessed with the War - Pink's dead war hero father hangs over the imagery, one of the single most striking things that happens is the British flag transforming into a blood-streaked cross in a military cemetery, and Fascist iconography is everywhere. As much as it's about the frustrations of celebrity or the anomie of modern life, Pink Floyd: The Wall is about the attractive pull of Fascist regimes to the conservative English soul; Pink's transformation into a neo-Nazi ideologue is less of a sign that he's been broken and split, than the inevitable expression of something that has been building throughout the movie, and Geldof is just terrifying in his savage facial expressions.

This all adds up to one of the more exceptional, unprecedented films to ever come from Great Britain, a guttural howl of rage at the darkest aspects of English culture from school to adulthood to the ease with which the nascent punk scene became a breeding ground for a very English form of neo-Nazism. Even without that, the film's depiction of Pink's wallowing in his own hedonism and self-hatred, and the grim potency of the animation are enough to make this a pretty heavy, dark experience. And here I go back to my little aside: maybe it's too effective. Let us not mince words: I love this film. But I don't make a habit of re-watching it. It's a raging, angry, hopeless movie - it doesn't exactly replicate the album's "all this will happen again and again" gesture, but it comes close to implying it - and everything about it that works works in the direction of making it as dark as possible. Still, nothing this potent can be discarded out of hand, and I'll happily call this a great piece of filmmaking. In fact, if I may commit a great heresy: while I'll never come close to watching the movie as often as I've listened to the album, I think the movie might actually be the superior embodiment of Waters's apocalyptic vision.

*Or at least the second-most obvious. The most obvious is maybe Parker's later adaptation of a '70s concept album, the 1996 film of Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim Rice's Evita, but it hardly seems sporting to bring that up.