If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail

I speak from personal experience in stating that being hypnotised is nothing like it's presented in pop culture (this is going someplace, I promise). It's not at all about blacking out and waking up without realising time has passed, but also now you're wearing a hat made out of your pants. It's more like... you're awake, but you don't really control your body, because you don't really want to control your body. You willingly act out the choices in your head, in perfectly sanguine acceptance of the fact that somebody else put them there. I suppose if somebody said "strangle this kitten", morality would kick in, but stick my finger in the air and wave it in a circle, that sounds perfectly fine, and why not just go with the flow, everything seems so peaceable when you go with the flow. Coming out of hypnosis is entering into a state of perfect relaxation, but also a little bit of melancholy that you need to start working your limbs again; it's like you were weightless, though you only realise it once you feel the weight of your body return. It's not exactly "waking up", it's like finally opening your eyes after you've been awake-ish for five or ten minutes already.

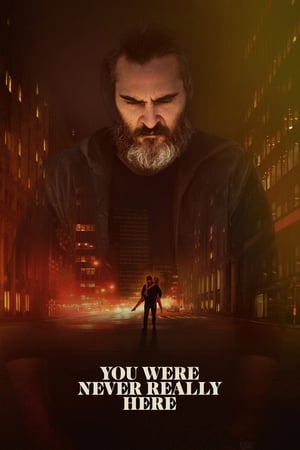

The reason I bring this up is that when the credit roll started at the end of You Were Never Really Here - which is a couple minutes after the actual end credits start - I was a little surprised to discover that I felt exactly the way I feel coming out of hypnosis. I have not ever once felt this way watching a movie. Oh sure, we all know the thing where a movie is "hypnotic", in the sense that you fall into a dreamy zone, so invested in the film's reality that when some outside stimulus reminds you that there's a real world, it's jolting. This wasn't that. I knew, the whole time, I was sitting in a movie theater; I knew I had to pee for the last 20 minutes, but not very bad; I knew my left leg was wedged in the wrong position and my knee would be telling me all about it later. I simply knew these things in a very passive way.

All of which is to say, You Were Never Really Here is a damnably hard movie for me to talk about rationally, and after a couple of false starts, I've decided it would be irresponsible of me to try. This was a movie that worked on me physically: mostly due to an awe-inspiring soundtrack, of which Jonny Greenwood's browbeating score is merely the most tangible aspect; sound designer Paul Davies and his team have brought together an extravagant collage of realistically-motivated sound effects being turned up and down in unrealistic ways, with subjective and objective bumping into each other like overheated molecules in a pressure chamber. In the most extreme cases, I felt as though I was being pinned to my seat, solely through sound design. I'm not sure how a trend of movies that played at Cannes in 2017 and which use form to extract a distressing physiological response came into being in the first place - a workprint of You Were Never Really Here played the festival (winning Best Actor, Best Screenplay, and the best critical notices of the official competition) six days after Yorgos Lanthimos's cinematographically nauseating The Killing of a Sacred Deer (which tied for that Best Screenplay citation*) - but is a trend I am altogether in favor of.

There is (although there almost needn't be) a plot attached to all of this. For only her fourth feature in 18 years, the great Scottish director Lynne Ramsay has adapted a 2013 novel by Jonathan Ames, telling the story of a deeply broken and despairing man named Joe (aforementioned award-winner Joaquin Phoenix). He's a war veteran, though that cannot possibly be enough to explain the fathomless hell inside him (any more than we can ever really know what's going on in the head of the title character of Ramsay's 2002 Morvern Callar, her masterpiece, and a film to which You Were Never Really Here plays as kind of a dark mirror, exploring brute masculinity instead of quicksilver femininity). Nor can it just be the shards of memory jutting into the film as a series of never fully explicated flashbacks, where we discover that young Joe (Dante Pereira-Olson) survived an abusive father.

Joe is a hitman, of sorts: he makes a living by taking jobs from McCleary (John Doman), a businessman in a fancy glass New York office, who indulges Joe's inarticulate weirdness by working through a middleman, bodega owner Angel (Frank Pando). Joe's jobs involving finding kidnapped girls, and not bothering too much about treating the kidnappers with any particular care. Since Joe's armament of choice is a ball-peen hammer, that lack of care manages to get incredibly messy. The latest job, the one that goes all corkscrew-shaped (for there must always be a corkscrew-shaped job, n'est-ce pas?) involves finding Nina Votto (Ekaterina Samsonov), the daughter of state senator Albert Votto (Alex Manette).

The plot elements are the primordial stuff of a thousand killer-for-higher thrillers; what makes You Were Never Really Here so immodestly special is just exactly what's implied by the title. Joe is both a completely surface-level cliché of post-traumatic masculinity, and and incomprehensible enigma; the film exists, in large part, as an exploration of the way that Joe exists in the world, if "exist" is even the word. This happens in the storytelling: he's shuffling and inexplicable, until he goes home to his beloved mother (Judith Roberts), so old and frail that her skin looks like it was painted on her skull (the film's one indefensible misstep is explicitly linking her with Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho, a comparison that anyway doesn't go beyond her physical appearance), a shocking visual contrast to her great, meaty bear of a son, with his snarl of greying beard. It happens very much in the performance: Phoenix doesn't so much "play" Joe as provide a channel for the film's energies, with expressions that aren't so much neutral as they are void. It happens in the structure, with those flashbacks that represent something Joe forbids himself from coherently remembering; and so, instead of following Screenwriting 101 and building up to a big climactic reveal, Ramsay wisely leaves them incoherent (though not incomprehensible).

It damn sure appears in the visual and sonic style; the sound I've talked about, so let me shift over to Tom Townend's excellent urban cinematography, capturing the velvety black essence of a night sky that has been coated over with a rainbow of unnatural colors (Townend has now shot a grand total of three features, of which I've seen only two; but between this and 2011's Attack the Block, I am prepared to call him one of our best living artists for capturing the peculiar lighting quality of cities at night). It's sort of "just" realism, but a realism so insistently real that it grows suffocating and stylistically overwhelming: demanding that we really fucking look at what light does, how it shapes and sculpts and hides, not out of a love for beauty, but something like a hunted animal paying attention to every aspect of its environment).

By all means, this is a brutalising, shattering movie, much more so than any of Ramsay's other films, and it's not like the psychologically torturous We Need to Talk About Kevin (her last film, from 2011) was anything other than overwhelmingly grim. I am frankly not sure that it's anything but brutalising and shattering: everything about it is centered around the viciousness that men do, from the basic matter of the plot to some of its most astonishing images, including one beautifully horrifying shot where thick, clumpy blood simply erupts onto Phoenix's non-responsive face. Its metanarrative is to look at the corpus of revenge thrillers, and say, "yes, but let us note that these stories are morally vacuous and the figures the celebrate are soul-dead" (not a new observation, and the film doesn't pretend it is: it pays explicit homage to Samuel Fuller, no stranger to a good expression of cosmic cynicism about celebrating violence). It has a happy ending, after a fashion; one couched inside the film's first outright declaration that Joe is at best clinically depressed, and whose conclusion might be summed up as "we have hope, but god-damned if we know what to do with it". And even then, the film's pointed final image, does not leave with the hopeful, but stays, staring at what they left behind.

Is this simply rugged, nasty miserabilism? I think it could be. It is certainly not concerned with avoiding that criticism. But it is so incredibly good at building up that lacerating, painful feeling through image, through sound, through psychology, through the agonies on Phoenix's face that almost resemble the blissed-out torment of Renaissance martyr paintings more than anything necessarily cinematic. It's the whole The Killing of a Sacred Deer thing: any movie that can work this much inside my body is obviously doing something right. Or maybe it's the Emily Dickinson thing, where she declared "If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry." You Were Never Really Here definitely made me cold; it definitely took the top of my head off; that's just for starters. It is deeply unsettling and wholly cinematic and outrageously powerful, and even if I can't, on just one viewing, articulate exactly what that power is, I know I want more of it.

*Reminding myself of this fact send me to look up the complete list of winners, and may I just say, the jury massively fucked up. I've now seen 13 of the films that were in competition, and I'd comfortably rank Palme d'Or winner The Square at #11.

The reason I bring this up is that when the credit roll started at the end of You Were Never Really Here - which is a couple minutes after the actual end credits start - I was a little surprised to discover that I felt exactly the way I feel coming out of hypnosis. I have not ever once felt this way watching a movie. Oh sure, we all know the thing where a movie is "hypnotic", in the sense that you fall into a dreamy zone, so invested in the film's reality that when some outside stimulus reminds you that there's a real world, it's jolting. This wasn't that. I knew, the whole time, I was sitting in a movie theater; I knew I had to pee for the last 20 minutes, but not very bad; I knew my left leg was wedged in the wrong position and my knee would be telling me all about it later. I simply knew these things in a very passive way.

All of which is to say, You Were Never Really Here is a damnably hard movie for me to talk about rationally, and after a couple of false starts, I've decided it would be irresponsible of me to try. This was a movie that worked on me physically: mostly due to an awe-inspiring soundtrack, of which Jonny Greenwood's browbeating score is merely the most tangible aspect; sound designer Paul Davies and his team have brought together an extravagant collage of realistically-motivated sound effects being turned up and down in unrealistic ways, with subjective and objective bumping into each other like overheated molecules in a pressure chamber. In the most extreme cases, I felt as though I was being pinned to my seat, solely through sound design. I'm not sure how a trend of movies that played at Cannes in 2017 and which use form to extract a distressing physiological response came into being in the first place - a workprint of You Were Never Really Here played the festival (winning Best Actor, Best Screenplay, and the best critical notices of the official competition) six days after Yorgos Lanthimos's cinematographically nauseating The Killing of a Sacred Deer (which tied for that Best Screenplay citation*) - but is a trend I am altogether in favor of.

There is (although there almost needn't be) a plot attached to all of this. For only her fourth feature in 18 years, the great Scottish director Lynne Ramsay has adapted a 2013 novel by Jonathan Ames, telling the story of a deeply broken and despairing man named Joe (aforementioned award-winner Joaquin Phoenix). He's a war veteran, though that cannot possibly be enough to explain the fathomless hell inside him (any more than we can ever really know what's going on in the head of the title character of Ramsay's 2002 Morvern Callar, her masterpiece, and a film to which You Were Never Really Here plays as kind of a dark mirror, exploring brute masculinity instead of quicksilver femininity). Nor can it just be the shards of memory jutting into the film as a series of never fully explicated flashbacks, where we discover that young Joe (Dante Pereira-Olson) survived an abusive father.

Joe is a hitman, of sorts: he makes a living by taking jobs from McCleary (John Doman), a businessman in a fancy glass New York office, who indulges Joe's inarticulate weirdness by working through a middleman, bodega owner Angel (Frank Pando). Joe's jobs involving finding kidnapped girls, and not bothering too much about treating the kidnappers with any particular care. Since Joe's armament of choice is a ball-peen hammer, that lack of care manages to get incredibly messy. The latest job, the one that goes all corkscrew-shaped (for there must always be a corkscrew-shaped job, n'est-ce pas?) involves finding Nina Votto (Ekaterina Samsonov), the daughter of state senator Albert Votto (Alex Manette).

The plot elements are the primordial stuff of a thousand killer-for-higher thrillers; what makes You Were Never Really Here so immodestly special is just exactly what's implied by the title. Joe is both a completely surface-level cliché of post-traumatic masculinity, and and incomprehensible enigma; the film exists, in large part, as an exploration of the way that Joe exists in the world, if "exist" is even the word. This happens in the storytelling: he's shuffling and inexplicable, until he goes home to his beloved mother (Judith Roberts), so old and frail that her skin looks like it was painted on her skull (the film's one indefensible misstep is explicitly linking her with Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho, a comparison that anyway doesn't go beyond her physical appearance), a shocking visual contrast to her great, meaty bear of a son, with his snarl of greying beard. It happens very much in the performance: Phoenix doesn't so much "play" Joe as provide a channel for the film's energies, with expressions that aren't so much neutral as they are void. It happens in the structure, with those flashbacks that represent something Joe forbids himself from coherently remembering; and so, instead of following Screenwriting 101 and building up to a big climactic reveal, Ramsay wisely leaves them incoherent (though not incomprehensible).

It damn sure appears in the visual and sonic style; the sound I've talked about, so let me shift over to Tom Townend's excellent urban cinematography, capturing the velvety black essence of a night sky that has been coated over with a rainbow of unnatural colors (Townend has now shot a grand total of three features, of which I've seen only two; but between this and 2011's Attack the Block, I am prepared to call him one of our best living artists for capturing the peculiar lighting quality of cities at night). It's sort of "just" realism, but a realism so insistently real that it grows suffocating and stylistically overwhelming: demanding that we really fucking look at what light does, how it shapes and sculpts and hides, not out of a love for beauty, but something like a hunted animal paying attention to every aspect of its environment).

By all means, this is a brutalising, shattering movie, much more so than any of Ramsay's other films, and it's not like the psychologically torturous We Need to Talk About Kevin (her last film, from 2011) was anything other than overwhelmingly grim. I am frankly not sure that it's anything but brutalising and shattering: everything about it is centered around the viciousness that men do, from the basic matter of the plot to some of its most astonishing images, including one beautifully horrifying shot where thick, clumpy blood simply erupts onto Phoenix's non-responsive face. Its metanarrative is to look at the corpus of revenge thrillers, and say, "yes, but let us note that these stories are morally vacuous and the figures the celebrate are soul-dead" (not a new observation, and the film doesn't pretend it is: it pays explicit homage to Samuel Fuller, no stranger to a good expression of cosmic cynicism about celebrating violence). It has a happy ending, after a fashion; one couched inside the film's first outright declaration that Joe is at best clinically depressed, and whose conclusion might be summed up as "we have hope, but god-damned if we know what to do with it". And even then, the film's pointed final image, does not leave with the hopeful, but stays, staring at what they left behind.

Is this simply rugged, nasty miserabilism? I think it could be. It is certainly not concerned with avoiding that criticism. But it is so incredibly good at building up that lacerating, painful feeling through image, through sound, through psychology, through the agonies on Phoenix's face that almost resemble the blissed-out torment of Renaissance martyr paintings more than anything necessarily cinematic. It's the whole The Killing of a Sacred Deer thing: any movie that can work this much inside my body is obviously doing something right. Or maybe it's the Emily Dickinson thing, where she declared "If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry." You Were Never Really Here definitely made me cold; it definitely took the top of my head off; that's just for starters. It is deeply unsettling and wholly cinematic and outrageously powerful, and even if I can't, on just one viewing, articulate exactly what that power is, I know I want more of it.

*Reminding myself of this fact send me to look up the complete list of winners, and may I just say, the jury massively fucked up. I've now seen 13 of the films that were in competition, and I'd comfortably rank Palme d'Or winner The Square at #11.

Categories: best of the 10s, thrillers, top 10, violence and gore