Folsom Prison blues

If one holds onto the belief that movies are first and above all meant to be emotion-generating objects (and this is not the only belief about movies one could hold, but it's the one I'm happy to stick with as an operating principle), one could hardly hope for a more movie-ish movie than The Work. The film is documentary, whose core subject is the unfettered expression of strong emotions. And sometimes those emotions are desperately uncomfortable to witness, for the other people on camera as well as for the film's audience. The result is maybe 2017's feelingest film, and maybe the most exhausting to watch, and those "maybes" are mostly just because I'm not God and I don't know everything about every movie made in the last year. But if there's a film that's more emotionally draining than The Work, I cannot imagine what it might be, or how it would be possible to survive the experience of watching it. Even at just 89 minutes, The Work is so overwhelming as to become numbing; I think it would be uncharitable, but not inaccurate, to say that it hits a point where watching human beings vomiting all their pain into the world triggers less of an extreme sympathetic result than a flattened "oh, more of this, then?" shrug.

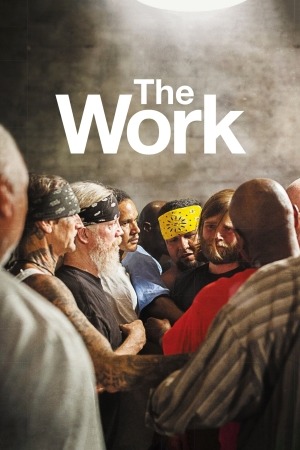

Directed by Jairus McLeary and co-directed by Gethin Aldous, with three of McLeary's brothers on hand to produce, The Work's subject is a therapy program held at Folsom State Prison in California. Every week, inmates are given an opportunity to attend group therapy sessions, and twice a year those sessions are converted into four-day therapy retreats that are opened up to civilians who think they could benefit from (and be of benefit to) the hardened inmates attempting make sense of their lives and past behaviors. The Work looks at one such retreat, focusing on three outsiders to Folsom each with their own reasons for wanting to be there: Charles, a bartender whose own father was imprisoned during his childhood; Chris, a museum employee whose hair and demeanor screech "dilettante liberal arts major", who seems to be in it for the thrill of it; and Brian, a teaching assistant with violence issues.

The filmmakers' approach to the material is to remain as hands-off as possible. It's easy to imagine a version of this film that goes straight for the warm and fuzzy glands, promising us that even in such a bleak place as Folsom, humanity can find an outlet. It's easy as well to imagine a slick advocacy doc, gushing about how great the therapy programs are, and how wonderful it would be is such programs were more widespread, or take your pick of advertising come-ons. Instead, this is pretty much just direct cinema, unvarnished by an editorial perspective of any particular sort. The camera watches as the men are given the rules, and continues to watch as a circle is formed, and watches still as the inmates and civilians alike dig deep into themselves and try to share what they find there.

It's a rough film, with all the aesthetic markers of raw documentary filmmaking: zooms and racking focus left in, errant snippets of footage that show the other camera operators in the background, and busted audio. Ah, the busted audio! It's an aesthetic motif all to itself in this movie. One of the things that happens a lot in the film is that someone will be whipped up into a state of such heightened, intense emotion that he needs to let it out in the form of a guttural bellow of rage and pain. When this happens, often as not, they get so loud that the audio recording equipment peaks, cutting off the volume with staticky distortion. Late in the film, during possibly its most enervating scene, one young convict admits that he's grown so hopeless at his multiple life sentences that he's contemplating suicide. The more seasoned prisoners give him some tough love, with an older man giving him a hug that crushes their lavaliere microphones between them. The filmmakers elect to use this audio, muffled and clunky, mercilessly piping in the throb of the two men's heartbeats. The whiplash of emotions is exquisite and palpable, moving from bottled-up fury into unbearable tension as the heartbeats create an implacable primeval rhythm; as they release their hug and the regular audio comes rushing back, it's like a rebirth.

The film's staggering blast of emotional moments is overwhelming rather than nuanced. There are themes to be teased out: one of these is the jarring contrast between the sincere desire for self-reflection and improvement on the part of the convicts, who seem to be genuinely distressed at they people they are and things they have done, and eager to heal themselves psychologically with no regard to whether they'll ever see the outside world again; and the callow misery tourism of the civilians, who need to have that sincerity drilled into them through four days in the darkness (I won't accuse anybody of fudging in the editing room, but the film maps out an uncommonly clear narrative arc for the three main subjects).

Another, more pronounced theme, is the idea of generational guilt, and the way that every man's story ultimately circles down to the twin demons of absent fathers (physically, emotionally, or both), and a culture of machismo that demands emotional sterility as a proof of being sufficiently masculine. The former of these is a little pat in its convenient Freudianism - a necessary component of the idea of "the work", derived from 12 step programs, which is maybe too much of a pop-psychology conceit for its own good - though the uniformity with which convicts and civilians alike end up cycling back to their unvoiced rage against their dads is enough to suggest that there's some kind of there there. The latter is, of course, central to the film's whole project. The Work asks us to recognise the terrible beauty of emotionally powerful moments, and to understand the difficulty it takes these men to allow themselves those moments. It is in part because these outbursts are so hard-won that they're so horrifying and moving, and especially so necessary. It feels almost uncomfortably intimate to be so close to the men while they have these moments, but then that's the very idea of the film: pushing towards that kind of intimacy, far beyond the point of comfort, is a necessary step in coming to terms with the darkness within one's self, and if The Work is an enormously unenjoyable movie, it's also incredibly human and filled with a wisdom that only comes from great suffering.

Directed by Jairus McLeary and co-directed by Gethin Aldous, with three of McLeary's brothers on hand to produce, The Work's subject is a therapy program held at Folsom State Prison in California. Every week, inmates are given an opportunity to attend group therapy sessions, and twice a year those sessions are converted into four-day therapy retreats that are opened up to civilians who think they could benefit from (and be of benefit to) the hardened inmates attempting make sense of their lives and past behaviors. The Work looks at one such retreat, focusing on three outsiders to Folsom each with their own reasons for wanting to be there: Charles, a bartender whose own father was imprisoned during his childhood; Chris, a museum employee whose hair and demeanor screech "dilettante liberal arts major", who seems to be in it for the thrill of it; and Brian, a teaching assistant with violence issues.

The filmmakers' approach to the material is to remain as hands-off as possible. It's easy to imagine a version of this film that goes straight for the warm and fuzzy glands, promising us that even in such a bleak place as Folsom, humanity can find an outlet. It's easy as well to imagine a slick advocacy doc, gushing about how great the therapy programs are, and how wonderful it would be is such programs were more widespread, or take your pick of advertising come-ons. Instead, this is pretty much just direct cinema, unvarnished by an editorial perspective of any particular sort. The camera watches as the men are given the rules, and continues to watch as a circle is formed, and watches still as the inmates and civilians alike dig deep into themselves and try to share what they find there.

It's a rough film, with all the aesthetic markers of raw documentary filmmaking: zooms and racking focus left in, errant snippets of footage that show the other camera operators in the background, and busted audio. Ah, the busted audio! It's an aesthetic motif all to itself in this movie. One of the things that happens a lot in the film is that someone will be whipped up into a state of such heightened, intense emotion that he needs to let it out in the form of a guttural bellow of rage and pain. When this happens, often as not, they get so loud that the audio recording equipment peaks, cutting off the volume with staticky distortion. Late in the film, during possibly its most enervating scene, one young convict admits that he's grown so hopeless at his multiple life sentences that he's contemplating suicide. The more seasoned prisoners give him some tough love, with an older man giving him a hug that crushes their lavaliere microphones between them. The filmmakers elect to use this audio, muffled and clunky, mercilessly piping in the throb of the two men's heartbeats. The whiplash of emotions is exquisite and palpable, moving from bottled-up fury into unbearable tension as the heartbeats create an implacable primeval rhythm; as they release their hug and the regular audio comes rushing back, it's like a rebirth.

The film's staggering blast of emotional moments is overwhelming rather than nuanced. There are themes to be teased out: one of these is the jarring contrast between the sincere desire for self-reflection and improvement on the part of the convicts, who seem to be genuinely distressed at they people they are and things they have done, and eager to heal themselves psychologically with no regard to whether they'll ever see the outside world again; and the callow misery tourism of the civilians, who need to have that sincerity drilled into them through four days in the darkness (I won't accuse anybody of fudging in the editing room, but the film maps out an uncommonly clear narrative arc for the three main subjects).

Another, more pronounced theme, is the idea of generational guilt, and the way that every man's story ultimately circles down to the twin demons of absent fathers (physically, emotionally, or both), and a culture of machismo that demands emotional sterility as a proof of being sufficiently masculine. The former of these is a little pat in its convenient Freudianism - a necessary component of the idea of "the work", derived from 12 step programs, which is maybe too much of a pop-psychology conceit for its own good - though the uniformity with which convicts and civilians alike end up cycling back to their unvoiced rage against their dads is enough to suggest that there's some kind of there there. The latter is, of course, central to the film's whole project. The Work asks us to recognise the terrible beauty of emotionally powerful moments, and to understand the difficulty it takes these men to allow themselves those moments. It is in part because these outbursts are so hard-won that they're so horrifying and moving, and especially so necessary. It feels almost uncomfortably intimate to be so close to the men while they have these moments, but then that's the very idea of the film: pushing towards that kind of intimacy, far beyond the point of comfort, is a necessary step in coming to terms with the darkness within one's self, and if The Work is an enormously unenjoyable movie, it's also incredibly human and filled with a wisdom that only comes from great suffering.