I think I need a new heart

A review requested by Chere Evans, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

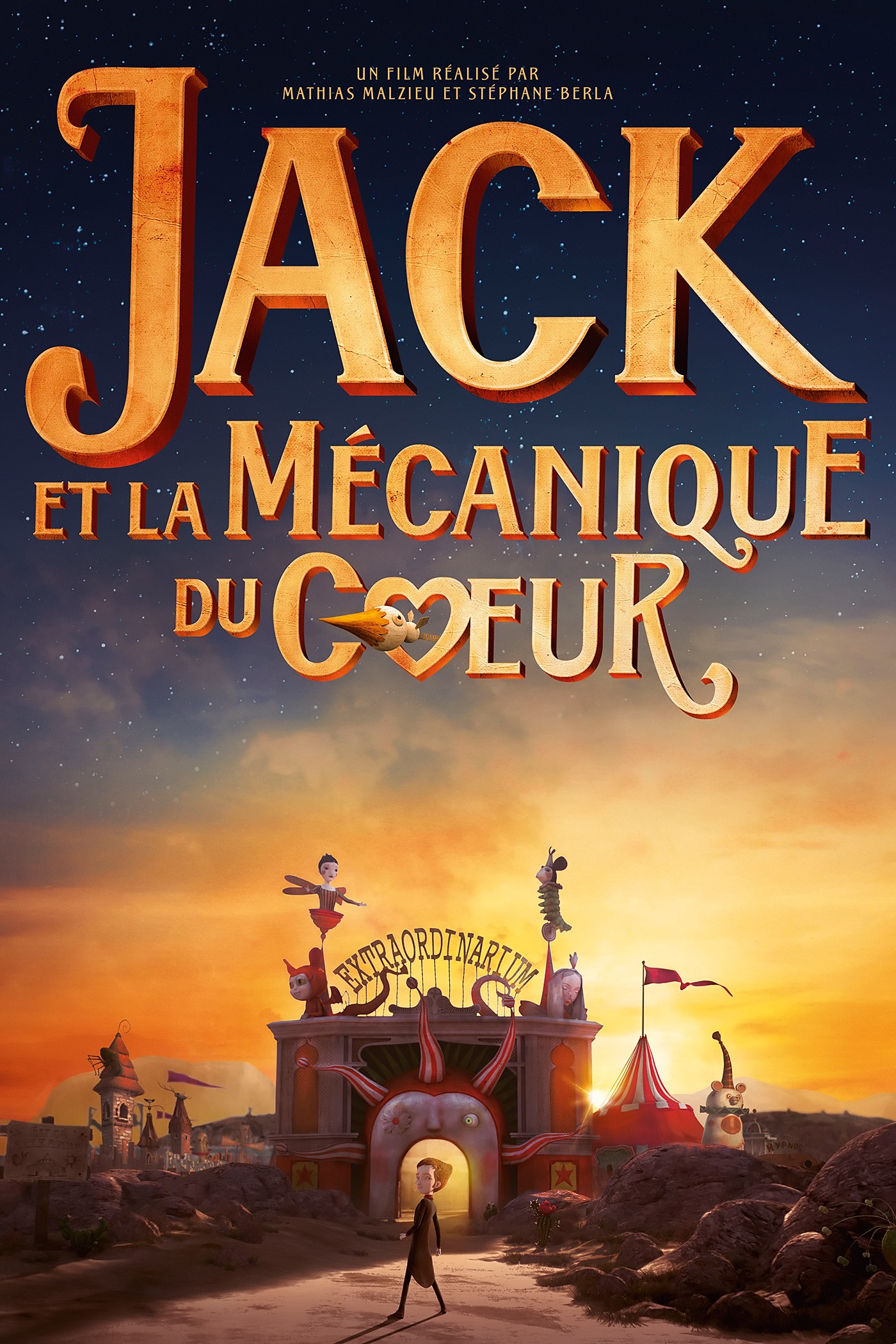

The word "weird" is among the vaguest and therefore least useful terms in art criticism. It is also not nearly sufficient to describe Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart, about which the most normative thing I can really say is that it's definitely in line with what I'd expect from a movie based off of a concept album based off of an illustrated novel inspired by Mathias Malzieu's deep love for the films of Tim Burton. Malzieu being the writer of the novel, the frontman of the band (French art-rockers Dionysos) that record the album, the screenwriter of the movie, and the primary credited director of the movie (Stéphane Berla, who'd done videos for Dionysos, is credited as "co-director"). So whatever else is true of Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart, don't you dare say that it's not a labor of love.

And that raises the question: whatever else is true of Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart? The answer is "many, many things", and this much I will say on the film's behalf: I suspect it's very hard to find it boring. The story begins in Edinburgh, in the 1870s, on the coldest day in the history of time. On this day, a little baby boy was born to a poor, helpless mother (Chloé Renaud in the original French version, Janet Dibley in Shout! Factory's English dub), who managed to collapse at the very door of the kindly midwife/inventor/possible witch Madeleine (Marie Vincent and Emily Loizeau splitting duties in French, Barbara Scaff going it alone in English, ), who helps deliver the child and makes the horribly discovery that the cold has frozen his heart solid. Thinking quickly, Madeleine replaces his heart with a small cuckoo clock keeping him alive and well, as long as he remembers to abide by three rules for the rest of his life: never touch the clock's hands, never lose his temper, and most importantly of all, never fall in love.

This goes fine until Jack's (Malzieu, Orlando Seale) 10th birthday, when Madeleine finally permits him to come into town with him on her errands. It does not, at this point, appear to be the dead of winter, incidentally. In town, he meets a girl his own age - later we'll learn that her name is Miss Acacia (Olivia Ruiz, Samantha Barks) - and falls in love with her bumbling nearsightedness and peculiar habit of sprouting thorns all over her body whenever she gets threatened. The remainder of the film finds Jack enrolling in school, and hopping on a train through Paris and into Spain, all in a years-long quest to find Miss Acacia after she mysteriously disappears from Edinburgh; when he finally catches up with her, accompanied by traveling magician and film camera inventor George Méliès (Jean Rochefort, Stephane Cornicard), it's at a strange little camp in the middle of the Andalusian wastes where various colorfully freakish figures put on a series of carnival shows, apparently for nobody but each other.

First, the trifling nitpick: George Méliès, the camera inventor? Fuck right off with that horseshit.

Second, the... rest. There is a whole lot of movie in Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart, which is all at once a delicate little nothing of a fairy tale, an homage to Burton's design sensibility and "love the weirdos" moral ethos (most especially The Nightmare Before Christmas), a celebration of Europe, a musical, a highly over-sexed kids' movie, and an attempt by Luc Besson's EuropaCorp to get in on the international animation marketplace. I am confident I missed at least a couple of things. Put 'em all together, and you have a dizzying-in-the-right-way-(mostly) mélange of some of the most fanciful imagery of any 2010s animated film I can name, and virtually none of it given any undue, leering attention. This is a film that learned all the right lessons from early Burton (and is, as a result, pretty close to being the best Burton film of the 21st Century), concocting a whole world full of distorted, horrific visions - of young women whose heads idly float above their bodies with little strings, like balloons; of rickety old buildings perched right at the edge of a geologically implausible cliff; of Jack's very own heart, a sweet-natured steampunk gag that never stops feeling altogether gross and creepy, especially when we peer out of his chest through the ticking gears - and treating them with unadulterated, unapologetic joy. Purely as a work of production design and mise en scène, this is tip-top stuff, in literally every detail, from the characters' fussily overdone clothing to the giant accordion train Jack flies (yes, flies) across Europe after barely evading Jack the Ripper (Alain Bashung, Howard Samuels), in an inexplicable, and effectively creepy cameo.

It's not, however, purely a work of production design and mise en scène. The story is trite and grinding; setting aside the eyebrow-raising notion of the film praising as "romantic" a 14-year-old boy making the choices Jack makes (particularly in the final scene), there's the more elemental matter of how gaudily misshapen the structure is. It's bad enough that it has the de rigueur twist where the lovers have a falling-out that could be resolved by rational actors in about 90 seconds; worse yet, the effect of this is to kludge a third-act chase structure onto a film that has not one reason to adopt a chase structure, except that Malzieu apparently believes along with too many other people that Pixar's narrative formula is the only one that works in animation. Basically, the film reunites Jack and Miss Acacia much too early, and then has to desperately stall to keep things from cutting off at the 60-minute mark, and this stalling is tedious.

The other enormous problem I have is with the film's animation, which makes this a good time to reiterate the important difference between "animation", which is the art of simulating movement though non-moving forms of visual art, and "art style/character design", which is what people tend to mean when they say "animation". Though frankly, I'm not sure that the characters here even succeed according to that second, inapt definition. There's a pinched quality to the "normal" human faces, strongly suggesting the Burton-derived designs of The Nightmare Before Christmas and Corpse Bride, which were of course designed to fill the needs of an entirely different production method and aesthetic. Basically, those characters are all meant to look like charming, spooky dolls. Jack, Acacia, Georges, and everybody are stuck in a CGI world, one taking its lighting rigging cues from the essentially realistic mode of Pixar, Disney, DreamWorks, and everybody. Their flat, smooth, eerily featureless computer-generated flesh just looks wrong, and that's that.

But here I am, talking about design and style when I meant to be going on about animation. It's really just not that good. There's a stiffness and robotic precision to how the character move through their actions, and coupled with the lack of flexible skin on their cheeks and unnaturally perfect, unmoving hair (particularly Acacia, who has thin locks of hair coming down her face on either side, and they tilt up and down with her head - a common enough shortcut in computer animation, and one that makes me feel every time I see it like a narrator from a Lovecraft story trying to name some eldritch abomination beyond human perception). I have a bad habit of complaining that cheap CGI can never be as good as cheap 2-D animation, since that at least can look arrestingly stylised, while CG's tendency to drift towards realism means that any imperfection is magnified. Well, dammit, it's a true complaint, and I'll keep making it as long as they keep making poorly-animated CG films.

A pity, though, because in most ways, Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart is sufficiently bizarre to be appealing more or less regardless of whether it "works". Even the hollowness of the animation sometimes turns to the film's benefit, as in the ride through the Ghost Train ride that Jack stars operating, a fancifully impossible world of video game physics and sickly green lighting, where the weightlessness of the character melds with the kitschy morbidity of Dionysos's music to create something awfully fun and light (the music is, in general, hard to quantify in such broad categories as "good" or "bad"; there's a self-conscious theatricality to it that is hugely pleasurably in the way of all unapologetically tacky grandeur - if you like tacky grandeur. Their music in no way resembles Jim Steinman's operatic cock rock, but I somehow feel like my positive response to the one is informed by my positive response to the other).

The whole thing has the certain merit of being enormously deranged without every deigning to acknowledge that fact. It's fully committed to its wonderfully mad visuals, to the unexplained but somehow consistent rules of the world it builds, to the spirit of morbid anarchy that attaches to everything. Oh how I wish it were better animated! The design is wonderfully fun and all, but the minute that ostensible humans start moving around in these amazing spaces, the whole thing becomes alienating and creepy in ways it surely didn't intend. This feels like the kind of movie that people who love it, really fucking love it, but for myself, I need to settle for mere admiration, and at arm's length.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

The word "weird" is among the vaguest and therefore least useful terms in art criticism. It is also not nearly sufficient to describe Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart, about which the most normative thing I can really say is that it's definitely in line with what I'd expect from a movie based off of a concept album based off of an illustrated novel inspired by Mathias Malzieu's deep love for the films of Tim Burton. Malzieu being the writer of the novel, the frontman of the band (French art-rockers Dionysos) that record the album, the screenwriter of the movie, and the primary credited director of the movie (Stéphane Berla, who'd done videos for Dionysos, is credited as "co-director"). So whatever else is true of Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart, don't you dare say that it's not a labor of love.

And that raises the question: whatever else is true of Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart? The answer is "many, many things", and this much I will say on the film's behalf: I suspect it's very hard to find it boring. The story begins in Edinburgh, in the 1870s, on the coldest day in the history of time. On this day, a little baby boy was born to a poor, helpless mother (Chloé Renaud in the original French version, Janet Dibley in Shout! Factory's English dub), who managed to collapse at the very door of the kindly midwife/inventor/possible witch Madeleine (Marie Vincent and Emily Loizeau splitting duties in French, Barbara Scaff going it alone in English, ), who helps deliver the child and makes the horribly discovery that the cold has frozen his heart solid. Thinking quickly, Madeleine replaces his heart with a small cuckoo clock keeping him alive and well, as long as he remembers to abide by three rules for the rest of his life: never touch the clock's hands, never lose his temper, and most importantly of all, never fall in love.

This goes fine until Jack's (Malzieu, Orlando Seale) 10th birthday, when Madeleine finally permits him to come into town with him on her errands. It does not, at this point, appear to be the dead of winter, incidentally. In town, he meets a girl his own age - later we'll learn that her name is Miss Acacia (Olivia Ruiz, Samantha Barks) - and falls in love with her bumbling nearsightedness and peculiar habit of sprouting thorns all over her body whenever she gets threatened. The remainder of the film finds Jack enrolling in school, and hopping on a train through Paris and into Spain, all in a years-long quest to find Miss Acacia after she mysteriously disappears from Edinburgh; when he finally catches up with her, accompanied by traveling magician and film camera inventor George Méliès (Jean Rochefort, Stephane Cornicard), it's at a strange little camp in the middle of the Andalusian wastes where various colorfully freakish figures put on a series of carnival shows, apparently for nobody but each other.

First, the trifling nitpick: George Méliès, the camera inventor? Fuck right off with that horseshit.

Second, the... rest. There is a whole lot of movie in Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart, which is all at once a delicate little nothing of a fairy tale, an homage to Burton's design sensibility and "love the weirdos" moral ethos (most especially The Nightmare Before Christmas), a celebration of Europe, a musical, a highly over-sexed kids' movie, and an attempt by Luc Besson's EuropaCorp to get in on the international animation marketplace. I am confident I missed at least a couple of things. Put 'em all together, and you have a dizzying-in-the-right-way-(mostly) mélange of some of the most fanciful imagery of any 2010s animated film I can name, and virtually none of it given any undue, leering attention. This is a film that learned all the right lessons from early Burton (and is, as a result, pretty close to being the best Burton film of the 21st Century), concocting a whole world full of distorted, horrific visions - of young women whose heads idly float above their bodies with little strings, like balloons; of rickety old buildings perched right at the edge of a geologically implausible cliff; of Jack's very own heart, a sweet-natured steampunk gag that never stops feeling altogether gross and creepy, especially when we peer out of his chest through the ticking gears - and treating them with unadulterated, unapologetic joy. Purely as a work of production design and mise en scène, this is tip-top stuff, in literally every detail, from the characters' fussily overdone clothing to the giant accordion train Jack flies (yes, flies) across Europe after barely evading Jack the Ripper (Alain Bashung, Howard Samuels), in an inexplicable, and effectively creepy cameo.

It's not, however, purely a work of production design and mise en scène. The story is trite and grinding; setting aside the eyebrow-raising notion of the film praising as "romantic" a 14-year-old boy making the choices Jack makes (particularly in the final scene), there's the more elemental matter of how gaudily misshapen the structure is. It's bad enough that it has the de rigueur twist where the lovers have a falling-out that could be resolved by rational actors in about 90 seconds; worse yet, the effect of this is to kludge a third-act chase structure onto a film that has not one reason to adopt a chase structure, except that Malzieu apparently believes along with too many other people that Pixar's narrative formula is the only one that works in animation. Basically, the film reunites Jack and Miss Acacia much too early, and then has to desperately stall to keep things from cutting off at the 60-minute mark, and this stalling is tedious.

The other enormous problem I have is with the film's animation, which makes this a good time to reiterate the important difference between "animation", which is the art of simulating movement though non-moving forms of visual art, and "art style/character design", which is what people tend to mean when they say "animation". Though frankly, I'm not sure that the characters here even succeed according to that second, inapt definition. There's a pinched quality to the "normal" human faces, strongly suggesting the Burton-derived designs of The Nightmare Before Christmas and Corpse Bride, which were of course designed to fill the needs of an entirely different production method and aesthetic. Basically, those characters are all meant to look like charming, spooky dolls. Jack, Acacia, Georges, and everybody are stuck in a CGI world, one taking its lighting rigging cues from the essentially realistic mode of Pixar, Disney, DreamWorks, and everybody. Their flat, smooth, eerily featureless computer-generated flesh just looks wrong, and that's that.

But here I am, talking about design and style when I meant to be going on about animation. It's really just not that good. There's a stiffness and robotic precision to how the character move through their actions, and coupled with the lack of flexible skin on their cheeks and unnaturally perfect, unmoving hair (particularly Acacia, who has thin locks of hair coming down her face on either side, and they tilt up and down with her head - a common enough shortcut in computer animation, and one that makes me feel every time I see it like a narrator from a Lovecraft story trying to name some eldritch abomination beyond human perception). I have a bad habit of complaining that cheap CGI can never be as good as cheap 2-D animation, since that at least can look arrestingly stylised, while CG's tendency to drift towards realism means that any imperfection is magnified. Well, dammit, it's a true complaint, and I'll keep making it as long as they keep making poorly-animated CG films.

A pity, though, because in most ways, Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart is sufficiently bizarre to be appealing more or less regardless of whether it "works". Even the hollowness of the animation sometimes turns to the film's benefit, as in the ride through the Ghost Train ride that Jack stars operating, a fancifully impossible world of video game physics and sickly green lighting, where the weightlessness of the character melds with the kitschy morbidity of Dionysos's music to create something awfully fun and light (the music is, in general, hard to quantify in such broad categories as "good" or "bad"; there's a self-conscious theatricality to it that is hugely pleasurably in the way of all unapologetically tacky grandeur - if you like tacky grandeur. Their music in no way resembles Jim Steinman's operatic cock rock, but I somehow feel like my positive response to the one is informed by my positive response to the other).

The whole thing has the certain merit of being enormously deranged without every deigning to acknowledge that fact. It's fully committed to its wonderfully mad visuals, to the unexplained but somehow consistent rules of the world it builds, to the spirit of morbid anarchy that attaches to everything. Oh how I wish it were better animated! The design is wonderfully fun and all, but the minute that ostensible humans start moving around in these amazing spaces, the whole thing becomes alienating and creepy in ways it surely didn't intend. This feels like the kind of movie that people who love it, really fucking love it, but for myself, I need to settle for mere admiration, and at arm's length.