Almost heaven

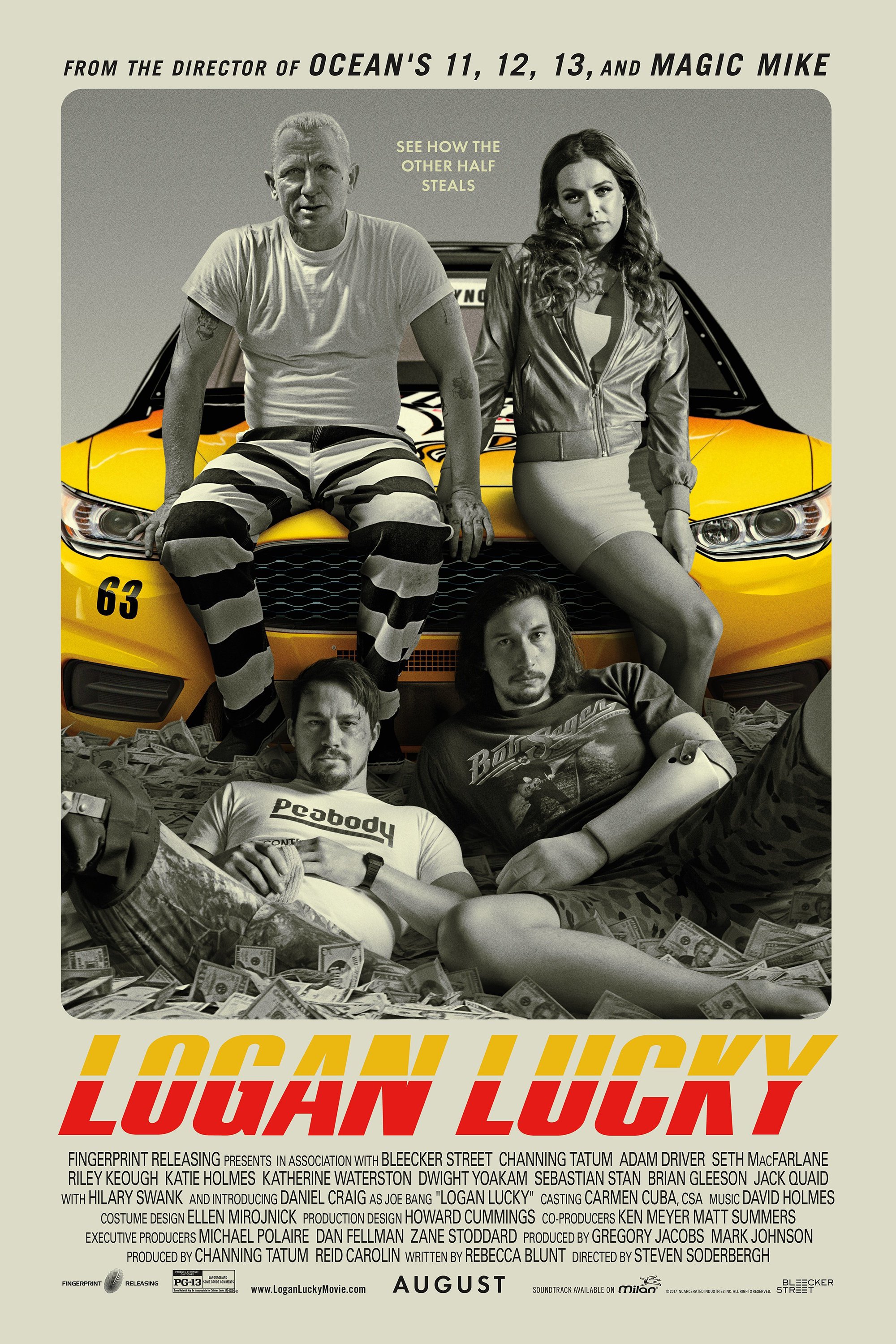

For his inevitable return to feature filmmaking after the busiest retirement in the history of the entertainment industry, Steven Soderbergh has looked backwards, kind of. He's never made a film exactly like Logan Lucky (a failed attempt at creating a new commercial opening for creator-driven mid-budget films, but otherwise one of the most effortless triumphs of the summer of 2017), but he's made films that are very similar. Indeed, I can't think of a more straightforward way to describe the new film than as the cross between Ocean's Eleven and Magic Mike, dressed up with a laid-back, summery sense of regionalism that has no particular forerunner in Soderbergh's career.

The result is a film that refuses to declare itself a major work by a major director (though I'd be a lot likelier to think in those terms if the story didn't lose the thread so badly in its final act), but is anyway quite a wonderful return to form: as frothy and frivolous as you want it, but humming with an undercurrent of burned-out working class melancholy if you want that. I have no grievances with Soderbergh's last two pre-retirement films from 2013, Side Effects and Behind the Candelabra, but Logan Lucky is, really, just way the hell better than them: smarter, funnier, more formally rigorous, more tonally shaggy, and with one of 2017's very best ensemble casts giving emotional and moral weight to the exuberant cartoons sketched out in the screenplay credited to Rebecca Blunt (who may or may not exist, but if she does, her screenwriting debut is a phenomenal master class in pinning down the cadences and obsessions of a particular milieu, in all its local color).

The basics: Jimmy Logan (Soderbergh muse Channing Tatum), born and raised his whole life in West Virginia, was once a high school football star, till he blew out his knee. Ever since then, he's floated around from job to job, stitching together an existence that, somewhere along the way, resulted in a daughter of about 9 or 10, Sadie (Farrah Mackenzie), and an ex-wife, Bobbie Jo (Katie Holmes), who has done much better for herself with husband #2, car dealer Moody Chapman (David Denman). So well that they're moving across the state line to Lynchburg, Virginia to open another dealership, which by the distinct cultural currents of West Virignia light might as well be another country. This happens the exact same day that Jimmy is let go from his latest short-term construction job, for reasons that seem flagrantly illegal (HR didn't want to deal with Jimmy's knee as a potential liability), but none of the people in this part of the world have much of an expectation that things will be fair or legal or any such optimistic thing.

And so Jimmy does as one will in this situation: he concocts a scheme to rob the Charlotte Motor Speedway down in North Carolina, with the help of his siblings, one-armed bartender Clyde (Adam Driver), and hairstylist Mellie (Riley Keough, the primus inter pares of the excellent cast), the latter of whom is the only Logan on record to have escaped the curse of bad luck that Clyde attends to the family. So in a way, this heist is not just a chance for Jimmy to redeem his own go-nowhere life and be the decent father he greatly wishes to be; it's a chance to redeem generations of Logans who toiled in obscure misery in mining country.

That, anyway, is the Magic Mike part of it: the sympathetic, blunt look at the lives of people who have been entirely swallowed up by the great beast of the American economy, which cares naught for their skills or sacrifices (Clyde, we are told, served two tours in Iraq, which is where his left hand went missing; this is brought up just often enough and in such a way that it's clear that the world of which he's a part views it as unjust when a crippled veteran can't make it in the world, but which is also conspicuously failing to help him in any way). The Ocean's Eleven part comes in the form of the heist itself, with Tatum ably playing the role of an Appalachian George Clooney, vastly less sophisticated in his charisma, but possessed of a similar quick wit and silver tongue. It's less crafty of a caper film, because the people and world are less showy than the glitzy Las Vegas settings of that 2001 movie; but no less involving for that, and arguably a good deal funnier. The screenplay strikes an impossibly fine line between mocking the culture it depicts from without and mocking it from within; there's a sense of deep understanding and love here, and if the film gets its share of cheap jokes about Southerners and NASCAR culture in, it also treats its subjects with an awful lot of tender loving care. When a sing-a-long to the (California) John Denver's "Take Me Home, Country Roads" breaks out at one point, the moment feels as heartfelt and sincere as anything in the reliably ironic Soderbergh's whole career, despite how wide open it leaves itself to being accused of wanton corniness. Lest we forget, the filmmaker himself was born in the American South.

And, accordingly, he films his locations with an extraordinary eye, one that combines the faultless formalism of his work with a documentarian's sensibility for finding the vibe of a place. Stylistically, this is the same approach the director-cinematographer-editor took to Magic Mike, only it's more successful here: the sense of tossed-off realism and the fascination with peering into the nooks and crannies where the film takes place remains, but the somewhat ill-advised color palette has been replaced by a slightly grainy, but otherwise highly naturalistic look. The framing is terrific throughout, relying to an unusually high degree on close-ups (and not just of people: one of the most striking images in the film is a practically microscopic look at cooking bacon), applied in a slightly clinical mode. We are, that is to say, being given a chance to examine the world here, to get to know it and become more familiar with the characters by having these things dominate our perceptions. Wide shots exist, almost always to quickly give us chance to react instinctively: the sprawling carnival atmosphere of the NASCAR crowd, to the Chapman's blocky McMansion, to the fascinating tangle of tubes where the thieves set themselves up. But it always returns its attention to details.

Anyway, I badly lost the thread myself. I was going on about the fact that this is, for all its strengths, still primarily a breezy lark of a heist film, with the cool grace of a more traditional story in this genre replaced with the warm slowness of the people it depicts. It's routinely hilarious, particularly Daniel Craig's snappy, Coenesque performance as Joe Bang, safecracker and sarcastic loudmouth (Craig is given the same "and introducing" card that Julia Roberts got in Ocean's Eleven, in a mildly disappointing retread of a fine, purposeful gag); just as often, it's so wry and methodical in its build-up to a gag that it's not "funny" in any active sense, but is neverthelessly entirely good-humored. It's quite an ingratiating film of a sort that, in all of the general details and most of the specifics could have been a major crowd-pleaser 40 years ago and will still probably be a major crowd-pleaser 40 years hence, if movies are still kicking around by then (though there is one ghastly misfire: a much-too-long Game of Thrones joke that has not a damn thing to do with anything else in the film). Nobody's idea of a game-changing movie, but I have a much harder time imagining the kind of person who'd hate this sort of thing than the person who'd love it.

I have, so far, described not just the best film of summer, 2017, but also maybe one of the most purely enjoyable films of the whole year, and I will happily say that for the first 90 minutes, that's just what I thought I was watching. And then, along comes a peculiar final act, one that resets the plot but doesn't bother to start up a new conflict, one that changes the tone completely in the form of Hilary Swank's very committed but not at all right FBI Agent Sarah Grayson (I imagine her clipped delivery style was designed to make it seem like she stands in contrast to the locals; it mostly just feels like she stumbled in from a bad action parody), and one that distends the clean shape of the movie till that point. It's bizarre how much effort the film needs to put in to go so thoroughly off the rails: the lazy choice would have been to simply button things up at the three-quarters mark and call it a film. No, this act was deliberate, though deliberately what, I cannot say.

All it actually succeeds in doing is leaving the film needlessly malformed, and oddly disappointing. The degree to which this is a problem is, I suppose, up to the individual viewer; even for myself, I can only imagine liking the film more the second time I view it, and I'm braced for the shift. And oh, there will definitely be a second time: even with its weak ending, Logan Lucky is terrific stuff, a bright entertainment and smart diagnosis of a culture in free fall, the ideal combination of grown-up concerns and childlike joy for big goofy movies, and a superb addition to the summer season as it winds to a close.

The result is a film that refuses to declare itself a major work by a major director (though I'd be a lot likelier to think in those terms if the story didn't lose the thread so badly in its final act), but is anyway quite a wonderful return to form: as frothy and frivolous as you want it, but humming with an undercurrent of burned-out working class melancholy if you want that. I have no grievances with Soderbergh's last two pre-retirement films from 2013, Side Effects and Behind the Candelabra, but Logan Lucky is, really, just way the hell better than them: smarter, funnier, more formally rigorous, more tonally shaggy, and with one of 2017's very best ensemble casts giving emotional and moral weight to the exuberant cartoons sketched out in the screenplay credited to Rebecca Blunt (who may or may not exist, but if she does, her screenwriting debut is a phenomenal master class in pinning down the cadences and obsessions of a particular milieu, in all its local color).

The basics: Jimmy Logan (Soderbergh muse Channing Tatum), born and raised his whole life in West Virginia, was once a high school football star, till he blew out his knee. Ever since then, he's floated around from job to job, stitching together an existence that, somewhere along the way, resulted in a daughter of about 9 or 10, Sadie (Farrah Mackenzie), and an ex-wife, Bobbie Jo (Katie Holmes), who has done much better for herself with husband #2, car dealer Moody Chapman (David Denman). So well that they're moving across the state line to Lynchburg, Virginia to open another dealership, which by the distinct cultural currents of West Virignia light might as well be another country. This happens the exact same day that Jimmy is let go from his latest short-term construction job, for reasons that seem flagrantly illegal (HR didn't want to deal with Jimmy's knee as a potential liability), but none of the people in this part of the world have much of an expectation that things will be fair or legal or any such optimistic thing.

And so Jimmy does as one will in this situation: he concocts a scheme to rob the Charlotte Motor Speedway down in North Carolina, with the help of his siblings, one-armed bartender Clyde (Adam Driver), and hairstylist Mellie (Riley Keough, the primus inter pares of the excellent cast), the latter of whom is the only Logan on record to have escaped the curse of bad luck that Clyde attends to the family. So in a way, this heist is not just a chance for Jimmy to redeem his own go-nowhere life and be the decent father he greatly wishes to be; it's a chance to redeem generations of Logans who toiled in obscure misery in mining country.

That, anyway, is the Magic Mike part of it: the sympathetic, blunt look at the lives of people who have been entirely swallowed up by the great beast of the American economy, which cares naught for their skills or sacrifices (Clyde, we are told, served two tours in Iraq, which is where his left hand went missing; this is brought up just often enough and in such a way that it's clear that the world of which he's a part views it as unjust when a crippled veteran can't make it in the world, but which is also conspicuously failing to help him in any way). The Ocean's Eleven part comes in the form of the heist itself, with Tatum ably playing the role of an Appalachian George Clooney, vastly less sophisticated in his charisma, but possessed of a similar quick wit and silver tongue. It's less crafty of a caper film, because the people and world are less showy than the glitzy Las Vegas settings of that 2001 movie; but no less involving for that, and arguably a good deal funnier. The screenplay strikes an impossibly fine line between mocking the culture it depicts from without and mocking it from within; there's a sense of deep understanding and love here, and if the film gets its share of cheap jokes about Southerners and NASCAR culture in, it also treats its subjects with an awful lot of tender loving care. When a sing-a-long to the (California) John Denver's "Take Me Home, Country Roads" breaks out at one point, the moment feels as heartfelt and sincere as anything in the reliably ironic Soderbergh's whole career, despite how wide open it leaves itself to being accused of wanton corniness. Lest we forget, the filmmaker himself was born in the American South.

And, accordingly, he films his locations with an extraordinary eye, one that combines the faultless formalism of his work with a documentarian's sensibility for finding the vibe of a place. Stylistically, this is the same approach the director-cinematographer-editor took to Magic Mike, only it's more successful here: the sense of tossed-off realism and the fascination with peering into the nooks and crannies where the film takes place remains, but the somewhat ill-advised color palette has been replaced by a slightly grainy, but otherwise highly naturalistic look. The framing is terrific throughout, relying to an unusually high degree on close-ups (and not just of people: one of the most striking images in the film is a practically microscopic look at cooking bacon), applied in a slightly clinical mode. We are, that is to say, being given a chance to examine the world here, to get to know it and become more familiar with the characters by having these things dominate our perceptions. Wide shots exist, almost always to quickly give us chance to react instinctively: the sprawling carnival atmosphere of the NASCAR crowd, to the Chapman's blocky McMansion, to the fascinating tangle of tubes where the thieves set themselves up. But it always returns its attention to details.

Anyway, I badly lost the thread myself. I was going on about the fact that this is, for all its strengths, still primarily a breezy lark of a heist film, with the cool grace of a more traditional story in this genre replaced with the warm slowness of the people it depicts. It's routinely hilarious, particularly Daniel Craig's snappy, Coenesque performance as Joe Bang, safecracker and sarcastic loudmouth (Craig is given the same "and introducing" card that Julia Roberts got in Ocean's Eleven, in a mildly disappointing retread of a fine, purposeful gag); just as often, it's so wry and methodical in its build-up to a gag that it's not "funny" in any active sense, but is neverthelessly entirely good-humored. It's quite an ingratiating film of a sort that, in all of the general details and most of the specifics could have been a major crowd-pleaser 40 years ago and will still probably be a major crowd-pleaser 40 years hence, if movies are still kicking around by then (though there is one ghastly misfire: a much-too-long Game of Thrones joke that has not a damn thing to do with anything else in the film). Nobody's idea of a game-changing movie, but I have a much harder time imagining the kind of person who'd hate this sort of thing than the person who'd love it.

I have, so far, described not just the best film of summer, 2017, but also maybe one of the most purely enjoyable films of the whole year, and I will happily say that for the first 90 minutes, that's just what I thought I was watching. And then, along comes a peculiar final act, one that resets the plot but doesn't bother to start up a new conflict, one that changes the tone completely in the form of Hilary Swank's very committed but not at all right FBI Agent Sarah Grayson (I imagine her clipped delivery style was designed to make it seem like she stands in contrast to the locals; it mostly just feels like she stumbled in from a bad action parody), and one that distends the clean shape of the movie till that point. It's bizarre how much effort the film needs to put in to go so thoroughly off the rails: the lazy choice would have been to simply button things up at the three-quarters mark and call it a film. No, this act was deliberate, though deliberately what, I cannot say.

All it actually succeeds in doing is leaving the film needlessly malformed, and oddly disappointing. The degree to which this is a problem is, I suppose, up to the individual viewer; even for myself, I can only imagine liking the film more the second time I view it, and I'm braced for the shift. And oh, there will definitely be a second time: even with its weak ending, Logan Lucky is terrific stuff, a bright entertainment and smart diagnosis of a culture in free fall, the ideal combination of grown-up concerns and childlike joy for big goofy movies, and a superb addition to the summer season as it winds to a close.