No use permitting some prophet of doom to wipe every smile away

TIM: I'd like to thank Zev Valancy for his contribution to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser & Review Auction, which in his case wasn't simply a run-of-the-mill review; for his money, he wanted to have to do some work. So his request was that he and I join forces for one of our semi-regular conversations about the thorny matter of stage-to-screen adaptations.

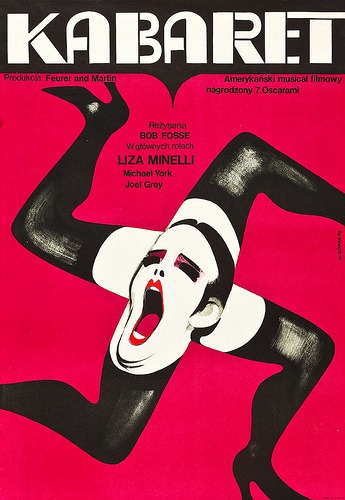

In the past, we've looked at such palpable misfires as Rob Marshall's unholy Nine and Julie Taymor's disastrous The Tempest, so when we came to Marshall's merely pedestrian Into the Woods it was a fairly dramatic step up in quality. But that wasn't enough for Zev, who has requested that we turn our attention now to an actual top-notch, masterpiece-level movie musical in the form of 1972's Cabaret, adapted by director Bob Fosse and screenwriter Jay Presson Allen from the 1966 stage musical with songs by John Kander and Fred Ebb and book by Joe Masteroff.

The Cabaret film is a paradox: it's a truly great movie adapted from truly great source material, but it achieves most of its greatness by thoroughly gutting and re-imagining that source. It's the reason I couldn't bear to put it on my list of the best stage-to-screen musical adaptations ever, even though it's easily better as cinema and mostly better as a musical than any of the ten films that made that list. We're going to get to the reasons that could possibly be true in a moment here, but first I'm going to hand the microphone over to Zev, for the necessary background about the stage Cabaret, why it's so gosh-damned important, and why virtually nobody under the age of 60 has ever seen it in the incarnation that premiered in '66.

ZEV: Thanks, Tim, for having me, as always, for the pleasure of talking about the world of theatre to film adaptations. And if you're interested in adaptation, there are few works more fruitful to explore than Cabaret.

By the time the musical reached the Broadway stage in 1966, it had already gone through several incarnations: novelist Christopher Isherwood drew on his own time in Weimar Berlin to write The Berlin Stories, published in 1945, (which combined the novellas Mr. Norris Changes Trains, from 1935, and Goodbye to Berlin, from 1939). That novel (mostly the Goodbye to Berlin portion) inspired John Van Druten's 1951 play I Am A Camera, which won Tony Awards for Julie Harris, playing Sally Bowles (her first of five Best Actress in a Play awards) and Marian Winters (Featured Actress), and was adapted into a 1955 film.

We probably don't need to recap the plot, but: all of the versions focus on the relationship between an expatriate aspiring novelist (named Christopher Isherwood in the novel and play, Clifford Bradshaw in the musical, and Brian Roberts in the film), with fellow expat Sally Bowles, a minimally-talented nightclub performer, seductive dynamo, and deeply immature woman, in the years before Hitler's rise. The nationalities of the central characters shift from medium to medium, as do the sexuality of the Isherwood stand-in and the identities and subplots of every other characters.

Harold Prince (legendary director and producer, winner of a staggering 21 Tony Awards, an essential figure in the development of the musical theatre, let’s not talk about his film career), acquired the rights to I Am a Camera, and hired book writer Joe Masteroff, composer John Kander, and lyricist Fred Ebb to transform it into a musical. Cabaret was only Kander and Ebb's second musical to be produced on Broadway, after a quick flop called Flora, the Red Menace, the Broadway debut of a 19-year-old Liza Minnelli (fun fact: Minnelli has only originated roles in three Broadway musicals, and all of them were written by Kander and Ebb). Prince directed, as well as producing, and Ronald Field choreographed. Jill Haworth played Sally (her reviews were mixed, and this was her first and last Broadway show), Bert Convy was Cliff, the legendary Lotte Lenya (widow of Kurt Weill and living embodiment of the spirit of Weimar Berlin) was landlady Fräulein Schneider, Jack Gilford was Herr Schultz, the Jewish fruit-seller with whom Schneider has a doomed romance, and Joel Grey was the Master of Ceremonies at the Kit Kat Club, where Sally performs.

The musical that they created did something that was truly startling: about two thirds of it was a relatively conventional book musical, with characters interacting in scenes and singing songs that express their emotions when mere words are not enough. It's a bit more frank in terms of politics and sex than most shows of the era, but nothing too extreme. But the opening and closing, along with several numbers in the middle, belong to Grey's Emcee, and the world of the cabaret: they seem to be numbers as part of the floor show, but they also comment on the political situation and the lives of the characters. It wasn't the first musical to include songs that commented on the action, rather than being a part of the main plot - the tradition goes back at least to Rodgers and Hammerstein's 1947 misfire Allegro (Come at me, Allegro fans. Its revolutionary status does not make it any less clunky or self-righteous.) - but it was the first one that really worked. The club is seductive, the Nazis are all too easy to ignore, and the ending packs a sickening punch.

The musical was a major success - it ran nearly three years, won eight Tonys, spun off a national tour and a London transfer (It starred Judi Dench, not yet a Dame, as Sally. Look up some clips some time.), and was turned into a movie. That version was directed by Bob Fosse, legendary Broadway director-choreographer and one of the only directors to do great work in both theatre and film. The changes he made to the original musical were drastic: the American Cliff is changed to the English Brian (Michael York), Sally is changed from English to American (Liza Minnelli, who is far more talented than the character, but who would object to that? More on her later.), Fräulein Schneider is reduced to bit part, and Herr Schultz is gone entirely. The older lovers are replaced by Maximilian and Natalia (Helmut Griem and Marisa Berenson), a much younger, equally doomed, couple.

But the biggest change Fosse made was the wholesale removal of all of the book songs. All songs in the film are diegetic - recognized as songs by the characters. Most happen within the cabaret, performed by Grey and Minnelli, with the exception of "Tomorrow Belongs to Me", the poisonously catchy Nazi anthem, sung in a beer garden. In addition, several of the cabaret songs were replaced with new songs that fit Minnelli's talents, so in the end, the musical and the film only have five songs (plus the finale, a reprise) in common. (In a nice touch, many of the cut songs are heard coming out of radios or gramophones.) The Emcee and the Kit Kat Club are still agents of commentary and disruption, but rather than commenting on a Rodgers and Hammerstein-style musical, they're commenting on a costume drama.

TIM: "Commenting on a costume drama" is a smart way to put it, but I want to add to that. I think it's worth keeping in mind the context of the movie musical at the time the film version of Cabaret was made. The 1960s were a period of much saggy bloat in the American studio movie, and nothing was more bloated or saggy than the mega-musicals that came out throughout that decade. The last big, unqualified hit was 1965's The Sound of Music, which gave hope to another half-decade of failed behemoths like 1967's Doctor Dolittle (which was an original piece), or that dread pair from 1969, Hello, Dolly! (which was adapted from a play) and Paint Your Wagon (an adaptation that's functionally an original piece). Fosse's own debut film, 1969's Sweet Charity, was a huge money pit that very nearly bankrupted Universal.

So part of what needed to happen with Cabaret was to make a deliberately small-scale musical, that backed off on the spectacle and replaced it with something little and gritty. Not to mention that the late 1960s/early 1970s were the height of politicised filmmaking in all of the major European/North American film countries (the U.S., France, Italy, even the U.K. in its own fashion). So I think it was exactly the right time for a musical that killed off all of its book numbers and told a story about the rise of Nazism in the face of a contented, self-indulgent culture. After all, what could have been more contented and self-indulgent than 1960s Hollywood?

That, anyway, is my theory for why Cabaret is so disinterested in being a book musical. It aspires to a level of psychological realism that audiences in 1972 would never have associated with a musical that didn't strictly ground its singing and dancing in a realistic context (but then, I think that's always been a bigger hang-up for movie audiences than theater audiences). And quite a strong piece of realism Cabaret does turn out to be, in certain important ways: the great cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth uses a great many of the techniques characteristic of the New Hollywood Cinema, including natural lighting and rough, documentary-style camera movements. With the help of a terrific al-German production design team headed up by Rolf Zehetbauer, Cabaret became American cinema's first really great, in-depth depiction of Weimar Berlin - being shot in Berlin helped, of course - at a time when movies about the end of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazism were enjoying an international vogue.

But there's absolutely no way we can simply say "oh, it's all about realism", and be done with it. The musical numbers, no matter how realistically motivated in the plot, still shift the energy of the film dramatically away from naturalism. It's the way they're staged, the way the audience sits unblinking and unmoving, like a bunch of wax sculptures, and the way the interior of the Kit Kat Club is framed: this is a heavily alien, unreal space. Do we ever even see doors leading in or out of the club? It's like a place that simply exists out of space, always present, impossible to leave or enter. Especially given the way Fosse and company treat the camera lens like a character - the way that Grey keeps staring right into the camera lens with a sly, insinuating look is sufficient all by itself to break all of the rules of cinematic realism. The design and staging of the cabaret interiors feel like we're watching the Expressionist id of Weimar Germany interrupting the straightforward early-'70s naturalism of the rest of the scenes, and the extreme disruption of saving the musical numbers for those moments, and only those moments, adds to the feeling of the cabaret as some essentially other place, narratively and aesthetically. Which adds a great deal to those sequences' ability to comment on the narrative.

At least, that's my take. What do you think is going on with how Cabaret-the-movie is different from Cabaret-the-show? And I know you're itching to talk about that Minnelli performance...

ZEV: Another important factor in how the film differs from the play is that the stage version was directed by Harold Prince, who generally had a strong directorial vision in his shows but was also a consummate collaborator. (Just ask Stephen Sondheim.) Fosse, on the other hand, was just about the closest thing to an auteur that mainstream American musical theatre has ever had. (Michael Bennett, of A Chorus Line, was the other contender for that title.) While auteur directors aren’t uncommon in the world of high-brow international theatre—a Peter Brook here, an Ariane Mnouchkine there, with Robert Wilson droning on in the background—it is much harder for a director to impose a singular vision in Broadway musicals, which are by their nature more prone to competing artistic visions and commercial concerns, and generally work best when several strong-willed creators fuse their visions into a greater whole.

By the time of Cabaret, though, Fosse was losing patience with the very notion of collaboration. Pippin, which premiered later in 1972, had a rehearsal period marked by Fosse locking the composer/lyricist out of the room, and the only two stage productions from the last decade of his life were Dancin’, a plotless revue of his own dances, set mostly to extant music or pieces commissioned for the show, and Big Deal, an ill-fated adaptation of Big Deal on Madonna Street, for which Fosse wrote his own book and which once again used extant music. So perhaps part of the explanation for Cabaret’s wholesale disjunction from its source material is simply Fosse’s desire to flex his muscles in the far more director-friendly world of film?

But leave aside the history and theory, and you have the film. Tim has already covered the way the design and cinematography help to create an impressively lived-in “real world” and terrifyingly alien Kit Kat Club, but a film about a cabaret wouldn’t work without performances, and this one has a couple of corkers.

First of all: yes, Liza Minnelli. She’s been a punchline for a long time now, and it's hard to deny that her shameless mannerisms and naked thirst for an audience’s love can make her a lot to take sometimes. But to revisit this film is to remind oneself that when she was at her peak, she was utterly magnetic. Her singing and dancing are superb, of course—her musical numbers are the reason that the word “sensational” was invented. But what I’d forgotten before re-watching the film was how well she acts in the book scenes: there’s an emotional transparency, a vulnerability, a sense of a woman spiraling out of control, that make for a really gorgeous all-around performance. (The film is fascinating in that, while York plays the nominal protagonist—and does quite creditable work—I think it would be hard to argue that anyone other than Minnelli is the film’s center).

And then there’s Joel Grey’s Emcee. He won both a Tony and and Oscar for the part, and what’s most fascinating to me is how well he scales his performance to film. It’s still a “theatrical” performance—there’s not a trace of realism in the unblinking eyes, the darting snake’s tongue, or the inhuman laugh. But it never feels like he’s playing to the second balcony—this is the alien force that whispers in your ear, not the one that dazzles you from the stage. I can’t say I’m surprised that his film career fizzled out afterwards - Who could figure out what to do with him? - but I’m disappointed that he never got the chance to give another film performance at this level.

What about you, Tim? Anything else to say about the performances or the rest of the film?

TIM: Well, with all due respect to an outstanding cast all in all - I am particularly fond of Marisa Berenson's slightly dumb-until-she's-not Natalia (a strange, but somehow perfect precursor to her tragic character in Kubrick's Barry Lyndon) - there's no real doubt that Minnelli and Grey are the two dominant forces in the movie, and you've done a great job talking about what I'd have touched on, particularly with Grey. So I'll avoid talking any more about the performances.

But jeez, how have we gotten this many words in and said so little about the choreography. Shit, you've got Fosse directing a movie musical, I'm a little thunderstruck that wasn't the first thing out of my mouth. Because the numbers in Cabaret are simply extraordinary, some of the best film dancing ever. The thing that I believe is particularly important to note about these dances is that they are staged with an eye towards the camera; even though he was working with a literal stage show in the reality of the story, Fosse was thinking entirely cinematically. This is most clear in "Mein Herr", a song written by Kander & Ebb for the movie (and I think it's no accident, as a result, that it's such a blazingly visual piece): the geometric positioning of Minnelli, and the shape of their moves, are designed to be seen from a very specific perspective, that of the camera lens. And on top of that, the scene is so crisply edited to drive home certain beats of the music. It is very much designed for the film viewer, not for anybody sitting in the Kit Kat Club, nor does it particularly care about the sanctity of the theatrical space, hopping around the stage as needed to get the right shot.

It's quite enough that the resulting number is so dazzling to look at - on top of everything, I do think it has the most satisfyingly sinuous choreography in the whole show, and the costumes are superbly iconic - but what really matters most, deep down, is that Fosse is making a film for us. Which sounds obvious and straightforward, but it's all in keeping with the way that the film breaks down the fourth wall and attacks us. We've both talked about how Grey's Emcee feels like he's targeting us specifically, and that gives a distinct sense of queasy discombobulation that successfully argues for the sense of moral rot that the material depicts. And insofar as this is a movie about the rise of Nazism, feeling grossed-out and rotten is, beyond a shadow of a doubt, an important effect that the material needs to have on the audience.

On the flipside, the whole point is that the cabaret is an enticement: it needs to be alluring and appealing, it needs to seduce us. There's no point to the cabaret or to Cabaret if it's an obvious hell; that part needs to creep up and catch us off guard. And the best way Fosse can ensure that happens is by creating such rich, gorgeously accomplished - and undeniably sexual - visual pleasures. You can only show us so many desperate people and incipient Nazis and fill us with a nauseous feeling about the perilous state of Berlin. If you're actually going to tell a proper story of this period and its politics, there needs to be something exciting and arousing, and the musical performances are it, I think. That, to me, is why it matters so much that Minnelli be allowed to open up and attack the material with guns blazing.

That, to me, is the great strength of Cabaret: it's a terribly exciting, fun movie to watch. Everything is horrible, and suffering is widespread, and we know what a miserable end this real-world story had, but it's such an intoxication! It's just like how that damned "Tomorrow Belongs to Me" is so legitimately rousing and catchy, even as we realise that it's catchy in service of pure evil. I think if Cabaret didn't hook us so hard, it wouldn't be able to have nearly the same power at the end, when it abruptly and cruelly jams on the brakes and leaves us to wallow in the sordidness all around us.

Anyway I love it to hell, and I could talk about it for another 10,000 words, but this is where I'm cutting myself off. What final thoughts do you have? Anything you desperately need to address that I left out?

ZEV: What I'm left with is a feeling that more film and stage directors need to learn Cabaret's lesson. Far too often, film adaptations of stage musicals (and increasingly, stage musicals based on film sources) try to ape their source material in structure, staging, and intended effect. (Watch a stage version of Cabaret that lifts the film choreography. It's not just the lack of Liza Minnelli that makes it feel a pale imitation.) A little more originality and attention to what makes the medium would make for a lot of way better art.

So there's the prescription: adapt a masterpiece, have complete confidence in your vision, and be a genius in multiple media. Cabaret, at least, makes it look easy.

Tim's rating:

Zev's rating:

In the past, we've looked at such palpable misfires as Rob Marshall's unholy Nine and Julie Taymor's disastrous The Tempest, so when we came to Marshall's merely pedestrian Into the Woods it was a fairly dramatic step up in quality. But that wasn't enough for Zev, who has requested that we turn our attention now to an actual top-notch, masterpiece-level movie musical in the form of 1972's Cabaret, adapted by director Bob Fosse and screenwriter Jay Presson Allen from the 1966 stage musical with songs by John Kander and Fred Ebb and book by Joe Masteroff.

The Cabaret film is a paradox: it's a truly great movie adapted from truly great source material, but it achieves most of its greatness by thoroughly gutting and re-imagining that source. It's the reason I couldn't bear to put it on my list of the best stage-to-screen musical adaptations ever, even though it's easily better as cinema and mostly better as a musical than any of the ten films that made that list. We're going to get to the reasons that could possibly be true in a moment here, but first I'm going to hand the microphone over to Zev, for the necessary background about the stage Cabaret, why it's so gosh-damned important, and why virtually nobody under the age of 60 has ever seen it in the incarnation that premiered in '66.

ZEV: Thanks, Tim, for having me, as always, for the pleasure of talking about the world of theatre to film adaptations. And if you're interested in adaptation, there are few works more fruitful to explore than Cabaret.

By the time the musical reached the Broadway stage in 1966, it had already gone through several incarnations: novelist Christopher Isherwood drew on his own time in Weimar Berlin to write The Berlin Stories, published in 1945, (which combined the novellas Mr. Norris Changes Trains, from 1935, and Goodbye to Berlin, from 1939). That novel (mostly the Goodbye to Berlin portion) inspired John Van Druten's 1951 play I Am A Camera, which won Tony Awards for Julie Harris, playing Sally Bowles (her first of five Best Actress in a Play awards) and Marian Winters (Featured Actress), and was adapted into a 1955 film.

We probably don't need to recap the plot, but: all of the versions focus on the relationship between an expatriate aspiring novelist (named Christopher Isherwood in the novel and play, Clifford Bradshaw in the musical, and Brian Roberts in the film), with fellow expat Sally Bowles, a minimally-talented nightclub performer, seductive dynamo, and deeply immature woman, in the years before Hitler's rise. The nationalities of the central characters shift from medium to medium, as do the sexuality of the Isherwood stand-in and the identities and subplots of every other characters.

Harold Prince (legendary director and producer, winner of a staggering 21 Tony Awards, an essential figure in the development of the musical theatre, let’s not talk about his film career), acquired the rights to I Am a Camera, and hired book writer Joe Masteroff, composer John Kander, and lyricist Fred Ebb to transform it into a musical. Cabaret was only Kander and Ebb's second musical to be produced on Broadway, after a quick flop called Flora, the Red Menace, the Broadway debut of a 19-year-old Liza Minnelli (fun fact: Minnelli has only originated roles in three Broadway musicals, and all of them were written by Kander and Ebb). Prince directed, as well as producing, and Ronald Field choreographed. Jill Haworth played Sally (her reviews were mixed, and this was her first and last Broadway show), Bert Convy was Cliff, the legendary Lotte Lenya (widow of Kurt Weill and living embodiment of the spirit of Weimar Berlin) was landlady Fräulein Schneider, Jack Gilford was Herr Schultz, the Jewish fruit-seller with whom Schneider has a doomed romance, and Joel Grey was the Master of Ceremonies at the Kit Kat Club, where Sally performs.

The musical that they created did something that was truly startling: about two thirds of it was a relatively conventional book musical, with characters interacting in scenes and singing songs that express their emotions when mere words are not enough. It's a bit more frank in terms of politics and sex than most shows of the era, but nothing too extreme. But the opening and closing, along with several numbers in the middle, belong to Grey's Emcee, and the world of the cabaret: they seem to be numbers as part of the floor show, but they also comment on the political situation and the lives of the characters. It wasn't the first musical to include songs that commented on the action, rather than being a part of the main plot - the tradition goes back at least to Rodgers and Hammerstein's 1947 misfire Allegro (Come at me, Allegro fans. Its revolutionary status does not make it any less clunky or self-righteous.) - but it was the first one that really worked. The club is seductive, the Nazis are all too easy to ignore, and the ending packs a sickening punch.

The musical was a major success - it ran nearly three years, won eight Tonys, spun off a national tour and a London transfer (It starred Judi Dench, not yet a Dame, as Sally. Look up some clips some time.), and was turned into a movie. That version was directed by Bob Fosse, legendary Broadway director-choreographer and one of the only directors to do great work in both theatre and film. The changes he made to the original musical were drastic: the American Cliff is changed to the English Brian (Michael York), Sally is changed from English to American (Liza Minnelli, who is far more talented than the character, but who would object to that? More on her later.), Fräulein Schneider is reduced to bit part, and Herr Schultz is gone entirely. The older lovers are replaced by Maximilian and Natalia (Helmut Griem and Marisa Berenson), a much younger, equally doomed, couple.

But the biggest change Fosse made was the wholesale removal of all of the book songs. All songs in the film are diegetic - recognized as songs by the characters. Most happen within the cabaret, performed by Grey and Minnelli, with the exception of "Tomorrow Belongs to Me", the poisonously catchy Nazi anthem, sung in a beer garden. In addition, several of the cabaret songs were replaced with new songs that fit Minnelli's talents, so in the end, the musical and the film only have five songs (plus the finale, a reprise) in common. (In a nice touch, many of the cut songs are heard coming out of radios or gramophones.) The Emcee and the Kit Kat Club are still agents of commentary and disruption, but rather than commenting on a Rodgers and Hammerstein-style musical, they're commenting on a costume drama.

TIM: "Commenting on a costume drama" is a smart way to put it, but I want to add to that. I think it's worth keeping in mind the context of the movie musical at the time the film version of Cabaret was made. The 1960s were a period of much saggy bloat in the American studio movie, and nothing was more bloated or saggy than the mega-musicals that came out throughout that decade. The last big, unqualified hit was 1965's The Sound of Music, which gave hope to another half-decade of failed behemoths like 1967's Doctor Dolittle (which was an original piece), or that dread pair from 1969, Hello, Dolly! (which was adapted from a play) and Paint Your Wagon (an adaptation that's functionally an original piece). Fosse's own debut film, 1969's Sweet Charity, was a huge money pit that very nearly bankrupted Universal.

So part of what needed to happen with Cabaret was to make a deliberately small-scale musical, that backed off on the spectacle and replaced it with something little and gritty. Not to mention that the late 1960s/early 1970s were the height of politicised filmmaking in all of the major European/North American film countries (the U.S., France, Italy, even the U.K. in its own fashion). So I think it was exactly the right time for a musical that killed off all of its book numbers and told a story about the rise of Nazism in the face of a contented, self-indulgent culture. After all, what could have been more contented and self-indulgent than 1960s Hollywood?

That, anyway, is my theory for why Cabaret is so disinterested in being a book musical. It aspires to a level of psychological realism that audiences in 1972 would never have associated with a musical that didn't strictly ground its singing and dancing in a realistic context (but then, I think that's always been a bigger hang-up for movie audiences than theater audiences). And quite a strong piece of realism Cabaret does turn out to be, in certain important ways: the great cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth uses a great many of the techniques characteristic of the New Hollywood Cinema, including natural lighting and rough, documentary-style camera movements. With the help of a terrific al-German production design team headed up by Rolf Zehetbauer, Cabaret became American cinema's first really great, in-depth depiction of Weimar Berlin - being shot in Berlin helped, of course - at a time when movies about the end of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazism were enjoying an international vogue.

But there's absolutely no way we can simply say "oh, it's all about realism", and be done with it. The musical numbers, no matter how realistically motivated in the plot, still shift the energy of the film dramatically away from naturalism. It's the way they're staged, the way the audience sits unblinking and unmoving, like a bunch of wax sculptures, and the way the interior of the Kit Kat Club is framed: this is a heavily alien, unreal space. Do we ever even see doors leading in or out of the club? It's like a place that simply exists out of space, always present, impossible to leave or enter. Especially given the way Fosse and company treat the camera lens like a character - the way that Grey keeps staring right into the camera lens with a sly, insinuating look is sufficient all by itself to break all of the rules of cinematic realism. The design and staging of the cabaret interiors feel like we're watching the Expressionist id of Weimar Germany interrupting the straightforward early-'70s naturalism of the rest of the scenes, and the extreme disruption of saving the musical numbers for those moments, and only those moments, adds to the feeling of the cabaret as some essentially other place, narratively and aesthetically. Which adds a great deal to those sequences' ability to comment on the narrative.

At least, that's my take. What do you think is going on with how Cabaret-the-movie is different from Cabaret-the-show? And I know you're itching to talk about that Minnelli performance...

ZEV: Another important factor in how the film differs from the play is that the stage version was directed by Harold Prince, who generally had a strong directorial vision in his shows but was also a consummate collaborator. (Just ask Stephen Sondheim.) Fosse, on the other hand, was just about the closest thing to an auteur that mainstream American musical theatre has ever had. (Michael Bennett, of A Chorus Line, was the other contender for that title.) While auteur directors aren’t uncommon in the world of high-brow international theatre—a Peter Brook here, an Ariane Mnouchkine there, with Robert Wilson droning on in the background—it is much harder for a director to impose a singular vision in Broadway musicals, which are by their nature more prone to competing artistic visions and commercial concerns, and generally work best when several strong-willed creators fuse their visions into a greater whole.

By the time of Cabaret, though, Fosse was losing patience with the very notion of collaboration. Pippin, which premiered later in 1972, had a rehearsal period marked by Fosse locking the composer/lyricist out of the room, and the only two stage productions from the last decade of his life were Dancin’, a plotless revue of his own dances, set mostly to extant music or pieces commissioned for the show, and Big Deal, an ill-fated adaptation of Big Deal on Madonna Street, for which Fosse wrote his own book and which once again used extant music. So perhaps part of the explanation for Cabaret’s wholesale disjunction from its source material is simply Fosse’s desire to flex his muscles in the far more director-friendly world of film?

But leave aside the history and theory, and you have the film. Tim has already covered the way the design and cinematography help to create an impressively lived-in “real world” and terrifyingly alien Kit Kat Club, but a film about a cabaret wouldn’t work without performances, and this one has a couple of corkers.

First of all: yes, Liza Minnelli. She’s been a punchline for a long time now, and it's hard to deny that her shameless mannerisms and naked thirst for an audience’s love can make her a lot to take sometimes. But to revisit this film is to remind oneself that when she was at her peak, she was utterly magnetic. Her singing and dancing are superb, of course—her musical numbers are the reason that the word “sensational” was invented. But what I’d forgotten before re-watching the film was how well she acts in the book scenes: there’s an emotional transparency, a vulnerability, a sense of a woman spiraling out of control, that make for a really gorgeous all-around performance. (The film is fascinating in that, while York plays the nominal protagonist—and does quite creditable work—I think it would be hard to argue that anyone other than Minnelli is the film’s center).

And then there’s Joel Grey’s Emcee. He won both a Tony and and Oscar for the part, and what’s most fascinating to me is how well he scales his performance to film. It’s still a “theatrical” performance—there’s not a trace of realism in the unblinking eyes, the darting snake’s tongue, or the inhuman laugh. But it never feels like he’s playing to the second balcony—this is the alien force that whispers in your ear, not the one that dazzles you from the stage. I can’t say I’m surprised that his film career fizzled out afterwards - Who could figure out what to do with him? - but I’m disappointed that he never got the chance to give another film performance at this level.

What about you, Tim? Anything else to say about the performances or the rest of the film?

TIM: Well, with all due respect to an outstanding cast all in all - I am particularly fond of Marisa Berenson's slightly dumb-until-she's-not Natalia (a strange, but somehow perfect precursor to her tragic character in Kubrick's Barry Lyndon) - there's no real doubt that Minnelli and Grey are the two dominant forces in the movie, and you've done a great job talking about what I'd have touched on, particularly with Grey. So I'll avoid talking any more about the performances.

But jeez, how have we gotten this many words in and said so little about the choreography. Shit, you've got Fosse directing a movie musical, I'm a little thunderstruck that wasn't the first thing out of my mouth. Because the numbers in Cabaret are simply extraordinary, some of the best film dancing ever. The thing that I believe is particularly important to note about these dances is that they are staged with an eye towards the camera; even though he was working with a literal stage show in the reality of the story, Fosse was thinking entirely cinematically. This is most clear in "Mein Herr", a song written by Kander & Ebb for the movie (and I think it's no accident, as a result, that it's such a blazingly visual piece): the geometric positioning of Minnelli, and the shape of their moves, are designed to be seen from a very specific perspective, that of the camera lens. And on top of that, the scene is so crisply edited to drive home certain beats of the music. It is very much designed for the film viewer, not for anybody sitting in the Kit Kat Club, nor does it particularly care about the sanctity of the theatrical space, hopping around the stage as needed to get the right shot.

It's quite enough that the resulting number is so dazzling to look at - on top of everything, I do think it has the most satisfyingly sinuous choreography in the whole show, and the costumes are superbly iconic - but what really matters most, deep down, is that Fosse is making a film for us. Which sounds obvious and straightforward, but it's all in keeping with the way that the film breaks down the fourth wall and attacks us. We've both talked about how Grey's Emcee feels like he's targeting us specifically, and that gives a distinct sense of queasy discombobulation that successfully argues for the sense of moral rot that the material depicts. And insofar as this is a movie about the rise of Nazism, feeling grossed-out and rotten is, beyond a shadow of a doubt, an important effect that the material needs to have on the audience.

On the flipside, the whole point is that the cabaret is an enticement: it needs to be alluring and appealing, it needs to seduce us. There's no point to the cabaret or to Cabaret if it's an obvious hell; that part needs to creep up and catch us off guard. And the best way Fosse can ensure that happens is by creating such rich, gorgeously accomplished - and undeniably sexual - visual pleasures. You can only show us so many desperate people and incipient Nazis and fill us with a nauseous feeling about the perilous state of Berlin. If you're actually going to tell a proper story of this period and its politics, there needs to be something exciting and arousing, and the musical performances are it, I think. That, to me, is why it matters so much that Minnelli be allowed to open up and attack the material with guns blazing.

That, to me, is the great strength of Cabaret: it's a terribly exciting, fun movie to watch. Everything is horrible, and suffering is widespread, and we know what a miserable end this real-world story had, but it's such an intoxication! It's just like how that damned "Tomorrow Belongs to Me" is so legitimately rousing and catchy, even as we realise that it's catchy in service of pure evil. I think if Cabaret didn't hook us so hard, it wouldn't be able to have nearly the same power at the end, when it abruptly and cruelly jams on the brakes and leaves us to wallow in the sordidness all around us.

Anyway I love it to hell, and I could talk about it for another 10,000 words, but this is where I'm cutting myself off. What final thoughts do you have? Anything you desperately need to address that I left out?

ZEV: What I'm left with is a feeling that more film and stage directors need to learn Cabaret's lesson. Far too often, film adaptations of stage musicals (and increasingly, stage musicals based on film sources) try to ape their source material in structure, staging, and intended effect. (Watch a stage version of Cabaret that lifts the film choreography. It's not just the lack of Liza Minnelli that makes it feel a pale imitation.) A little more originality and attention to what makes the medium would make for a lot of way better art.

So there's the prescription: adapt a masterpiece, have complete confidence in your vision, and be a genius in multiple media. Cabaret, at least, makes it look easy.

Tim's rating:

Zev's rating: