An evil that great in this beautiful world... finally, does it matter what the cause?

Return to the complete Twin Peaks index

Written by Mark Frost & Harley Peyton & Robert Engels

Directed by Tim Hunter

Airdate: 1 December, 1990

So we've arrived: this is the end of the uninterrupted 17-episode stretch of original recipe Twin Peaks as one of the greatest and very possibly the greatest television series in American history. The next 12 episodes will sometimes still be very good TV (and they will, to be deadly certain, sometimes not be), but the drop in quality is decisively and severe, and it is not reversed until the show's very last episode, at which point things go in some very strange third direction, anyway.

Conveniently enough, Episode 16 really does feel like a nice end point, and makes for one of the most natural bailing-out points that any serial television series has left us. Most of the show's ongoing plotlines have been brought a point of closure, or at least a point where we feel like we can trust that things will work themselves out, and the writers have the good sense to leave the only plotline where that's definitely not true (Nadine's post-traumatic emotional regression to high school) entirely offscreen, so we at least have the opportunity to forget about it until later. Of course, it's not the final episode, and it was never intended to be, but even so... it's a strong epilogue to the Twin Peaks-that-has-been, leaving me a bit more satisfied than I would necessarily expect to be, or even want to be left by a David Lynch project, but then this has never been only a Lynch project, and not for nothing was this episode co-written by series co-creator Mark Frost (his last direct contribution to the show until Episode 26).

The whole thing is a headlong rush of plot interspersed with brief moments of philosophical reflection, and mostly it handles these things well. The bookending scenes that open and close the episode (both involving four men walking in the woods, and three of the same men each time) have some particularly fine writing and acting on the philosophical side of things. The finale scene especially, granting each character a different chance to offer a thematic synopsis of the show's moral universe, most pithily offered by Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer) as "the evil men do", such a concise, blunt little statement (and nicely echoing a more explicit Shakespeare quote earlier in the scene) that it leaves me ready to forgive Albert for showing up in this episode where he doesn't really belong.

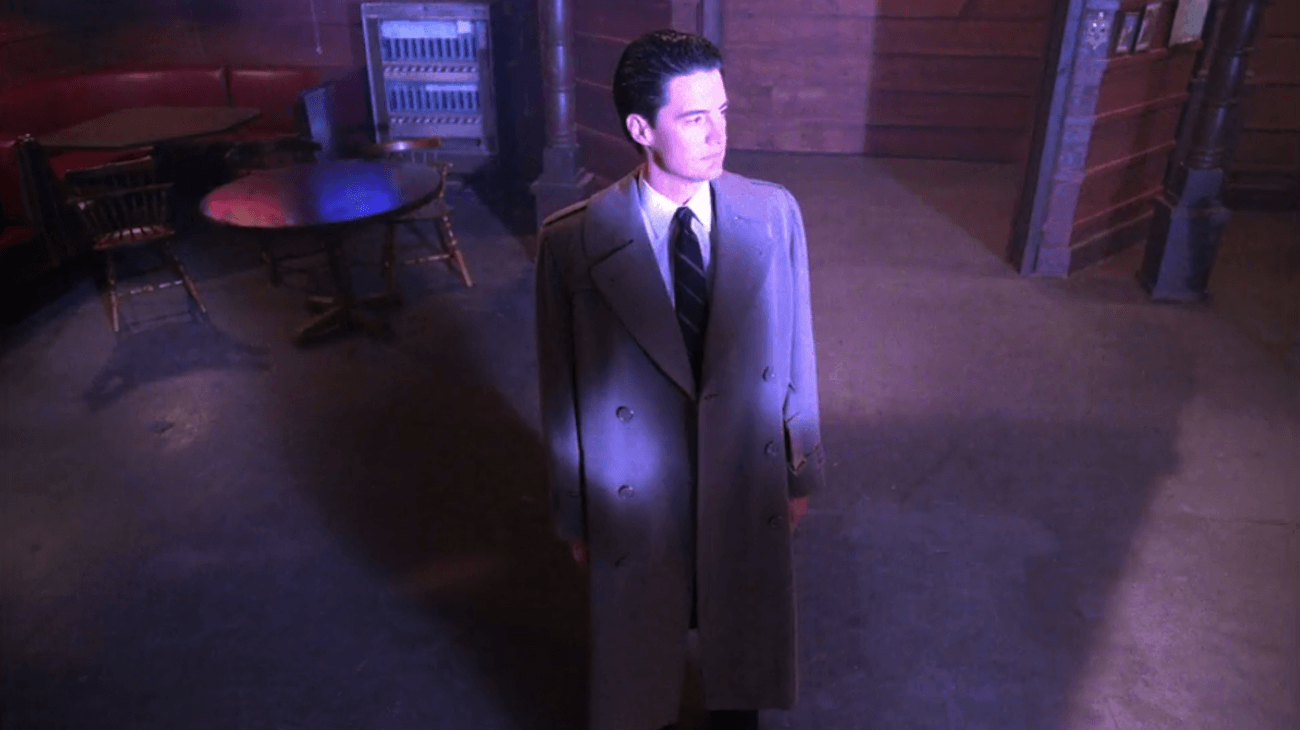

The headlong rush is much more what the episode is about, though, and it makes for a hell of an interesting contrast with the solemn stillness of Episode 15. It's not exactly that it's jam-packed full of stuff, the way that Episode 12 and Episode 13 are; it's more the way it has an urgent, unyielding momentum like we've been dropped at the cusp of that waterfall we see in the opening credits and within most episodes, and are being dragged helplessly towards the edge. It's a very inevitable episode, not because we necessarily know at the start that it will end with Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) ripping the mask off of Leland Palmer (Ray Wise). Though I think we do pick that up. It's that same sense of things coming to an end: Catherine Martell (Piper Laurie, who is just do delectably self-satisfied during this stretch of the show) finally humiliates and beats Ben Horne (Richard Beymer); James (James Marshall) is so overwhelmed with the grief and alienation that have been tugging at him all show, that he finally leaves a confused and saddened Donna (Lara Flynn Boyle), though sadly he'll return soon enough. There is a sense that t's are being crossed and i's dotted, that the show is clearing the decks for us.

And as far as the main plotline is concerned, it's all just build, and build, and build, until finally it erupts (more or less literally, in that hellacious sprinkler storm). The acting, Wise's in particular, does a lot of that work: in his scene with Donna, you can almost see Leland ripping apart at the seams, the actor superbly playing a remorseless killer mangling an attempt to seem friendly and fatherly. He speaks with a harshness that doesn't even sound like Wise's voice. It's clearly a center that cannot hold for even a little bit longer, and the second half of the episode basically becomes a waiting game for the moment that Bob (Frank Silva) finally tears Leland apart.

A lot of the credit also has to go to Tim Hunter's direction. I had nothing much nice to say about his previous work for the show, in Episode 4, and even in his much improved form, he's not quite as good at putting his own spin on the material as Lesli Linka Glatter, or as good at copying Lynch as Duwayne Dunham. But he does a lot of good for the episode, particularly in his use of acute angles all throughout. Not just the strong canted angles he pulls out right from the start, either, though those serve their purpose. This is an episode with a substantial number of high-angle compositions, all over the place: looking down at Norma's (Peggy Lipton) insulting mother Vivian (Jane Greer) and the plate in front of her (which is enough to make this not-awful, though it's still not a subplot I have any real interest in), Ben prostrating himself in jail, Bob screaming with pleasure in the sprinkler, and many of the shots in the Roadhouse, where Cooper stages the first half of what I can only think to call his exorcism. And there are some low angles, too, and low camera heights (the camera sits just at table height while Lucy (Kimmy Robertson) berates Andy (Harry Goaz) and Dick (Ian Buchanan), making the two men look like little kids at the adult table, which is just about exactly right), but it's the high angles that really hit home. The feeling I get, at least, is of constant pressure, of something literally pressing down on the characters and their actions, no matter how innocuous or momentous. There's a weight to the images in this episode, and that, to me, is the heart of what makes it work so damn well: that immense heaviness neatly mimics the fate that everything is propelling towards.

Hunter's not without his missteps: the worst part of the episode, and quite possibly the worst moment in the series to date, is a series of still images of all the important cast members gathered in the Roadhouse, illuminated by the bolt of lightning that strikes the moment Cooper remembers the phrase "that gum you like is going to come back in style". It's needlessly over-dramatic, emphasising a moment that the dialogue already explains just fine, and it's a gaudy, cheap-looking effect besides. Also, for all that Wise sells the hell out of everything he does and every word he says in this episode, his dying monologue is as protracted and repetitive as a death aria in an 18th Century opera. Nor does Cooper's spiritual words of wisdom to the pathetic murder redeem it; I have a hard time understanding how a writing team that included Frost could end up giving Cooper dialogue that sounded so artificial and downright pretentious, but there it is.

Still, these are clumsy moments in an episode that otherwise sweeps in with the force of the storm that we see midway through the episode. It is heaving, robust, terribly unsubtle, and at times feels like a whole bunch of crescendos, but that's just what I like about it: the main plotline of Twin Peaks comes to its grand, miserable close here, and that's worthy of some dramatic excess.

Grade: A

Written by Mark Frost & Harley Peyton & Robert Engels

Directed by Tim Hunter

Airdate: 1 December, 1990

So we've arrived: this is the end of the uninterrupted 17-episode stretch of original recipe Twin Peaks as one of the greatest and very possibly the greatest television series in American history. The next 12 episodes will sometimes still be very good TV (and they will, to be deadly certain, sometimes not be), but the drop in quality is decisively and severe, and it is not reversed until the show's very last episode, at which point things go in some very strange third direction, anyway.

Conveniently enough, Episode 16 really does feel like a nice end point, and makes for one of the most natural bailing-out points that any serial television series has left us. Most of the show's ongoing plotlines have been brought a point of closure, or at least a point where we feel like we can trust that things will work themselves out, and the writers have the good sense to leave the only plotline where that's definitely not true (Nadine's post-traumatic emotional regression to high school) entirely offscreen, so we at least have the opportunity to forget about it until later. Of course, it's not the final episode, and it was never intended to be, but even so... it's a strong epilogue to the Twin Peaks-that-has-been, leaving me a bit more satisfied than I would necessarily expect to be, or even want to be left by a David Lynch project, but then this has never been only a Lynch project, and not for nothing was this episode co-written by series co-creator Mark Frost (his last direct contribution to the show until Episode 26).

The whole thing is a headlong rush of plot interspersed with brief moments of philosophical reflection, and mostly it handles these things well. The bookending scenes that open and close the episode (both involving four men walking in the woods, and three of the same men each time) have some particularly fine writing and acting on the philosophical side of things. The finale scene especially, granting each character a different chance to offer a thematic synopsis of the show's moral universe, most pithily offered by Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer) as "the evil men do", such a concise, blunt little statement (and nicely echoing a more explicit Shakespeare quote earlier in the scene) that it leaves me ready to forgive Albert for showing up in this episode where he doesn't really belong.

The headlong rush is much more what the episode is about, though, and it makes for a hell of an interesting contrast with the solemn stillness of Episode 15. It's not exactly that it's jam-packed full of stuff, the way that Episode 12 and Episode 13 are; it's more the way it has an urgent, unyielding momentum like we've been dropped at the cusp of that waterfall we see in the opening credits and within most episodes, and are being dragged helplessly towards the edge. It's a very inevitable episode, not because we necessarily know at the start that it will end with Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) ripping the mask off of Leland Palmer (Ray Wise). Though I think we do pick that up. It's that same sense of things coming to an end: Catherine Martell (Piper Laurie, who is just do delectably self-satisfied during this stretch of the show) finally humiliates and beats Ben Horne (Richard Beymer); James (James Marshall) is so overwhelmed with the grief and alienation that have been tugging at him all show, that he finally leaves a confused and saddened Donna (Lara Flynn Boyle), though sadly he'll return soon enough. There is a sense that t's are being crossed and i's dotted, that the show is clearing the decks for us.

And as far as the main plotline is concerned, it's all just build, and build, and build, until finally it erupts (more or less literally, in that hellacious sprinkler storm). The acting, Wise's in particular, does a lot of that work: in his scene with Donna, you can almost see Leland ripping apart at the seams, the actor superbly playing a remorseless killer mangling an attempt to seem friendly and fatherly. He speaks with a harshness that doesn't even sound like Wise's voice. It's clearly a center that cannot hold for even a little bit longer, and the second half of the episode basically becomes a waiting game for the moment that Bob (Frank Silva) finally tears Leland apart.

A lot of the credit also has to go to Tim Hunter's direction. I had nothing much nice to say about his previous work for the show, in Episode 4, and even in his much improved form, he's not quite as good at putting his own spin on the material as Lesli Linka Glatter, or as good at copying Lynch as Duwayne Dunham. But he does a lot of good for the episode, particularly in his use of acute angles all throughout. Not just the strong canted angles he pulls out right from the start, either, though those serve their purpose. This is an episode with a substantial number of high-angle compositions, all over the place: looking down at Norma's (Peggy Lipton) insulting mother Vivian (Jane Greer) and the plate in front of her (which is enough to make this not-awful, though it's still not a subplot I have any real interest in), Ben prostrating himself in jail, Bob screaming with pleasure in the sprinkler, and many of the shots in the Roadhouse, where Cooper stages the first half of what I can only think to call his exorcism. And there are some low angles, too, and low camera heights (the camera sits just at table height while Lucy (Kimmy Robertson) berates Andy (Harry Goaz) and Dick (Ian Buchanan), making the two men look like little kids at the adult table, which is just about exactly right), but it's the high angles that really hit home. The feeling I get, at least, is of constant pressure, of something literally pressing down on the characters and their actions, no matter how innocuous or momentous. There's a weight to the images in this episode, and that, to me, is the heart of what makes it work so damn well: that immense heaviness neatly mimics the fate that everything is propelling towards.

Hunter's not without his missteps: the worst part of the episode, and quite possibly the worst moment in the series to date, is a series of still images of all the important cast members gathered in the Roadhouse, illuminated by the bolt of lightning that strikes the moment Cooper remembers the phrase "that gum you like is going to come back in style". It's needlessly over-dramatic, emphasising a moment that the dialogue already explains just fine, and it's a gaudy, cheap-looking effect besides. Also, for all that Wise sells the hell out of everything he does and every word he says in this episode, his dying monologue is as protracted and repetitive as a death aria in an 18th Century opera. Nor does Cooper's spiritual words of wisdom to the pathetic murder redeem it; I have a hard time understanding how a writing team that included Frost could end up giving Cooper dialogue that sounded so artificial and downright pretentious, but there it is.

Still, these are clumsy moments in an episode that otherwise sweeps in with the force of the storm that we see midway through the episode. It is heaving, robust, terribly unsubtle, and at times feels like a whole bunch of crescendos, but that's just what I like about it: the main plotline of Twin Peaks comes to its grand, miserable close here, and that's worthy of some dramatic excess.

Grade: A

Categories: television, twin peaks