Someday this war's gonna end

A second review requested by Patton with thanks for contributing twice to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

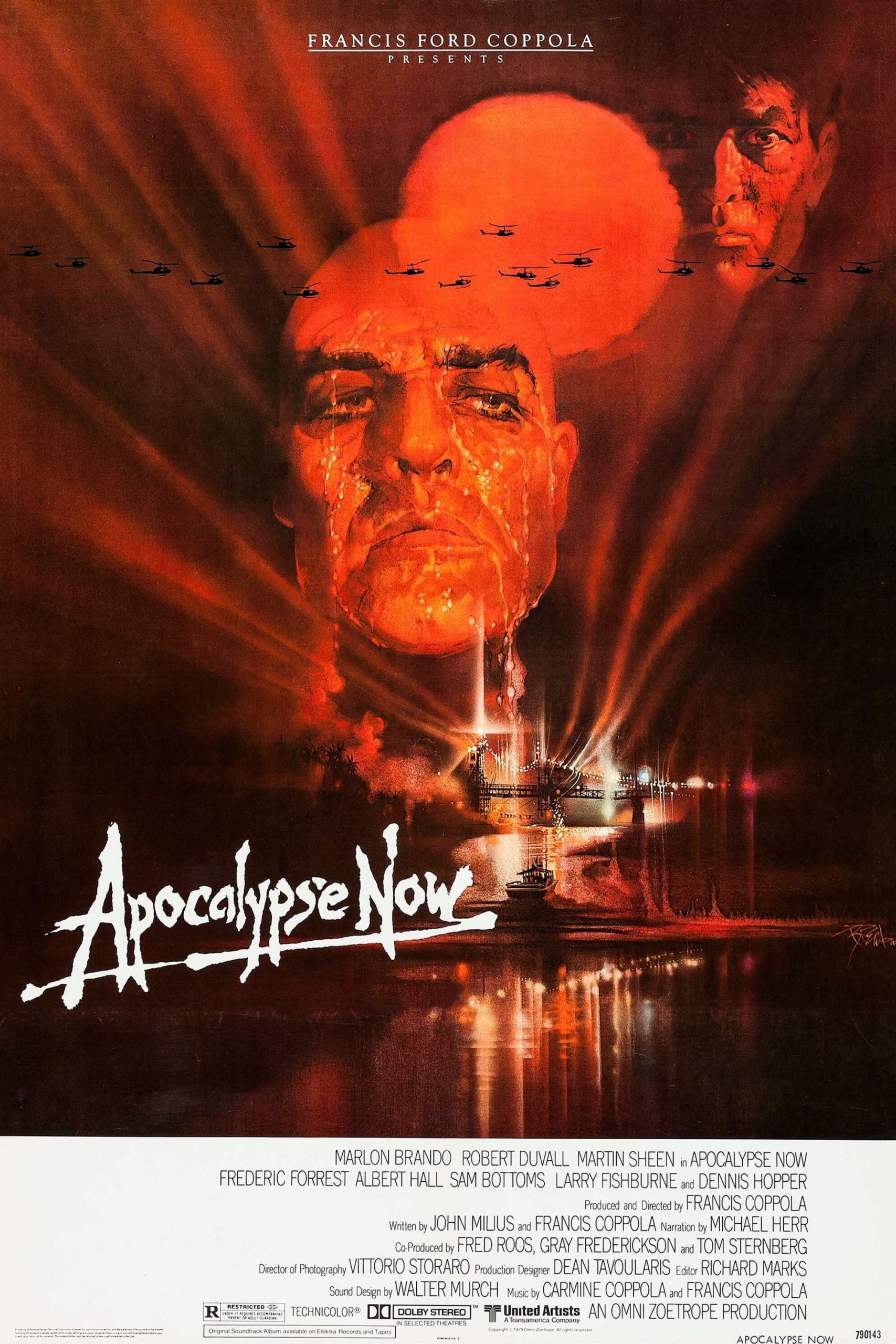

How in the name of the good Lord does one even go about starting to discuss Apocalypse Now? It's among the small population of films about which I think it's more or less impossible to speak about it qualitatively, i.e. whether it is "good" or "bad", whether it "works" or "fails". It is a movie that simply is, in all its epic lumpiness and horrid beauty and genuine madness. Genuine madness. Director/ringmaster Francis Ford Coppola infamously said of the production, "My film is not a movie. My film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam", and this is more or less what he meant: the creation of the film was an exercise in Americans with too damn much money going into the jungle, losing their minds, and turning out something awfully close to a disaster. And yet good enough to be the only film to ever win the Palme d'Or at Cannes in 1979 despite not being finished when it screened there. It's a film that wears the scars of its production on its body: star Martin Sheen's miserable grappling with personal demons and Marlon Brando's rambling, dictatorial refusal to do anything the director asked of him directly map onto the characters they're playing, and the sense of things spinning out of control as the movie starts to shed narrative cohesion and well-defined continuity more or less precisely described the actual process of a shot that engorged itself from six weeks to sixteen months, resulted in multiple heart attacks, and more or less required the filmmakers to actually re-stage a war in the Philippines, while that country was wracked with violent political tensions.

I'll not go into the production history at too much greater length, in part because Apocalypse Now happens to have been served with one of the all-time best making-of documentaries in cinema history, the 1991 Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse, which is just as essential viewing as Apocalypse Now itself (I myself first saw the documentary before I had ever seen the feature, for what it's worth), and almost certainly a cleaner, more articulate version of the same basic story: people go into the jungle with straightforward plans, completely lose their minds as a result. It is a sublime coincidence that this is the exact same plot as the other candidate for all-time best making-of documentary, Les Blank's Burden of Dreams, about Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo. It occurs to me that if you had a full day and wanted to utterly exhausted at the end of it, you could hardly program a better quadruple feature.

The point being, anyway, if you want to see the story that Apocalypse Now tells, told with utmost clarity and jaw-dropping true stories about people rushing to the brink of insanity, you should watch Hearts of Darkness. If you want to watch the hallucinatory fever dream version of the story, just stick with Apocalypse Now itself. That's not to say that one is better than the other; the fact is, I have never once watched Apocalypse Now and at the end of it thought to myself, "what a wholly satisfying experience about which I have no significant reservations". Quite the contrary, the film is an astounding fucking mess: it took three credited editors - Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Walter Murch - almost three years to tame Coppola's swirling vortex of footage into a two-and-a-half hour object that could be satisfactorily released as a feature (22 years later, Coppola and Murch returned to rework it and add several sequences as Apocalypse Now Redux, a re-edit that I mostly oppose; to me, the ideal cut of the film is the 1979 70mm version that includes neither opening nor closing credits, with the plantation scene re-instituted in Redux but none of its other changes. Ah well, can't have everything). And what they came up with starts to disintegrate anyway, leading to a film that rivals only Easy Rider, its exact counterpart from 1969 (they are to my mind the first and last films of the "pure" New Hollywood Cinema), for encoding in its very form the unhinged derangement of the actions it depicts. And like Easy Rider, I find it supremely off-putting and indulgent and disorienting to the point of nausea. But I suppose I should talk about the beginning of the movie before the ending.

In its final form, which took most of a decade to write, and passed through the hands of John Milius and George Lucas before Coppola finally took on directorial duties, Apocalypse Now is an adaptation of Joseph Conrad's 1899 Heart of Darkness, though Conrad's work has been so thoroughly reconceived and in some important ways directly inverted that it's probably fair that the novel wasn't credited as a source. The basic throughline is the same, though: in 1969 (never explicitly stated, but easily identified thanks to a news story about the Tate murders) a drunken, spiritually desolate U.S. Army Captain, Benjamin Willard (Sheen) is given orders to travel downriver until he finds the compound where Colonel Walter Kurtz (Brando) has established a cult of some sort or another, ruling over a native tribe as a demi-god. Willard's journey into the Vietnam jungle reveals to him the complete absence of morality or immorality in the nihilistic vacuum of war. By the time Willard and what's left of his PBR crew arrive at Kurtz's compound, the captain barely resembles a functioning member of the U.S. military any more than his messianic quarry.

The film breaks fairly clearly into four unequal parts sprinkled between three acts: the mission prep, the first half of the journey that mostly involves Willard's encounter with the gung-ho surfing psychopath Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) - amazingly, "Kilgore" is the subtler name for the character, replacing "Carnage" - the second half of the journey, in which we see a USO show that resembles a sequence from The Pilgrim's Progress more than anything, as the PBR crew starts dying horribly, and then last, the surrealistic events at Kurtz's compound. The aesthetic dissimilarities between the acts are so complete that it genuinely feels like we're watching three wholly unique movies, though it is the case that the film generally evolves as it goes along: that is, the middle section, the longest and best part of the movie, gradually moves towards the misty, opaque horror of the final act, after starting off in essentially the same banal everyday style of the opening sequences (and I suppose I should excuse the very first scene from that consideration: it is neither banal nor everyday, but an exemplary mood piece carried off by The Doors' droning, apocalyptic "The End", and some fucking beautiful dissolves and straight cuts that feel like a plunge into the throes of a powerful drunken rager - Sheen's or Willard's, I can't say).

This strong division into segments is very much in line with the film's express themes and intentions, which are to depict a descent into hell. It does not do this entirely in the "right" order, though surely none of us would shift things around. The idyll with Kilgore, who turns a coastal village into a wasteland of napalm to that he can go surfing, feels like an oddly sudden escalation in all ways. The famous thing about this sequence, of course, is the heaving vocals of the "Walkürenritt" motif from Wagner's Die Walküre (surely better known to English-speakers as "Ride of the Valkyries"), played as diegetic music by Kilgore to... pump himself and his mean up? Put terror into the souls of the Vietnamese? The real answer, of course, is to provide Coppola with a a suitably grandiose aural landscape as he depicts the countryside being torn to hell in amazing aerial vistas that later give way to fire-wreathed long shots that stand Willard, quite dazed, in the remains of what was once a place and has now become Hell on Earth. As with so much of Apocalypse Now, the place where opposition to the arbitrary violence of war ends and the celebration of war as a massive-scale spectacle begins is quite impossible to pinpoint; one gets the strong impression that the filmmakers were too buried in the scale of what they were up to, to stop and think about the morality of it. The film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam.

It's almost certainly the most viscerally-involving extended sequence in the movie, so why not move it later? Simply, because it's a mere primer: it's not actually about anything. Snip it out and the plot is unchanged. It is the exaggerated, over-the-top depiction of war-as-event that prepares us to see much smaller-scale violence and atrocities meted out in a much more intimate setting, the same way that a Broadway musical leads with one of its biggest numbers. And sure enough, the second half of the river sequence is damned powerful, as we see the crew members - "Chef" Hicks (Frederic Forrest), Chief Petty Officer Phillips (Albert Hall), Lance Johnson (Sam Bottoms), "Mr. Clean" Miller (Laurence Fishburne, young enough to be going under "Larry" still) - caught up in Willard's mythic drive towards death. There are squirrely, vaguely funny scenes; there are horrifying scenes; there are unbearably sad scenes, like the one that trains the camera on one character's face as he stares at another character's dead body, while a sweet, homey letter is read placidly on the soundtrack.

Capturing all of this is one of the best-shot American films of the '70s, augmented by one of the best sound mixes ever: Murch was responsible for the soundscape as well, and it's fair to say that what he achieved redefined what sound in movies could in fact be (Apocalypse Now, following Star Wars, is one of the defining films in the establishment of 5.1 surround sound as a technical and artistic tool). The all-encompassing sounds of war and the jungle, flailing about space before and behind us, is awe-inspiring, putting Apocalypse Now in the holy trinity of great films about the sound of war, alongside All Quiet on the Western Front and Saving Private Ryan, and it is probably the most impressive achievement of them all, if only for how it also incorporates Carmine Coppola's aggressively toneless, violently synthetic music as a kind of aural wall. It sounds so utterly great that you can overlook how this is one of the greatest-looking films in the career of the genius cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, shifting with brute force from relatively natural settings to shocking fields of practically monochrome war zones: yellow combat, icy blue jungles, orange sunsets that irradiate the landscape in nuclear holocaust. And, then he pulls out an entirely new basket of tricks in the final act, often using just a solitary key light to draw as much emphasis to the deadly blackness that he's interrupting with slices of lighting. It's a flawless visual depiction of the world as a toxic, expressionist fun house, beautiful and ugly.

Anyway, how about that ending? I will confess that my exhaustion with it is inextricable with my general antipathy towards Brando, who I regard as the single most over-appreciated artist in American cinema. Even if that weren't the case, there's no real argument that Apocalypse Now finds him at his best: showing up on set have having exploded into obesity and totally disinterested in learning his lines or even the plot of the movie, he required the entire project to be re-formed around him - Storaro's amazing nighttime photography is in part an attempt to show the least amount of Brando as can be gotten away with, in the hope of suggesting a hulking muscular brute rather than a fat actor (this does not work). Most of his dialogue consists of meandering philosophical and poetic discursions, chasing stream-of-consciousness rabbits where they'll take him. It's bracing and unexpected, to be sure; but it is, for me at least, even more grotesque and annoying. Whispered, over-dramatic lines of dialogue aren't the film's strong suit - it suffers throughout from Willard's breathy, reflective voice-over, written by Michael Herr, and Brando's musings are like an even more intrusive version of that voice-over.

It's where the film breaks: Apocalypse Now is in large part a film about how its director could not keep control, and Brando's arrival on set is where Coppola finally lost the movie once and for all. It's fascinating, by all means, but it's also the most sordid, indulgent kind of filmmaking imaginable, emblematic of the dark side of New Hollywood filmmaking, in which filmmakers allow their films to collapse just for the organic beauty of it. Easy Rider had its drug fantasia that's so boldly unattractive and shrill that you kind of have to admire its commitment to anti-narrative savagery. A year after Apocalypse Now opened, Michael Cimino would chase this kind of purposefully formless aesthetic into the mega-bomb Heaven's Gate, thereby killing the New Hollywood ethos off completely, and I am painfully in love with the film. Apocalypse Now, for its part, is one of the all-time glorious messes: even more than in Easy Rider, it becomes largely impossible to parse, except in general terms, what's happening and how space is laid out, and instead the concluding action plays out asa series of fragments of actions stitched together by Eisensteinian editing techniques and the logic of whatever horrible dreams the filmmakers suffered out their in the jungle. As much as I can't stand the film for staging the brutal slaughter of a water buffalo for a symbolic point (contra Coppola's claims that he simply filmed a ritual already taking place), there's a certain rightness to it: the wantonness, the excessive, the feeling of destruction for the sake of destruction is exactly in line with everything else in the last act, where meaning itself seems to fall apart in favor of striking images and intense actions that follow intuitively rather than logically.

I invariably feel drained and unsatisfied when this part of the movie ends; I can't really complain, since there seems no reason in the world to assume that Apocalypse Now gives a shit about whether I or anybody is satisfied. It is a film about losing your mind and your self to the savage madness of the world: Vietnam in 1969 is the case study, but the film obviously has something more cosmic in mind than that. Anyway, it is well and right that the film itself should break down into meaninglessness, an all-time supreme example of form and content intimately speaking to each other to create theme. I don't have to like it, and I frankly have never decided if the final 40 minutes aren't so acutely disordered, indulgent, and tediously beholden to all of Brando's very worst habits that they make Apocalypse Now, as a whole, a "bad movie". Who gives a shit. Good or bad, success or failure, this is a magnificent, gonzo piece of cinema, and the art form would be far lesser if it had never existed.

Act I: 7/10

Act II: 10/10

Act III: 5/10

Cinematography: 10/10

Editing: 8/10

Score: 8/10

Sound Mix: 11/10

Marlon Brando: ?/10

The Vietnam War: 2/10

How in the name of the good Lord does one even go about starting to discuss Apocalypse Now? It's among the small population of films about which I think it's more or less impossible to speak about it qualitatively, i.e. whether it is "good" or "bad", whether it "works" or "fails". It is a movie that simply is, in all its epic lumpiness and horrid beauty and genuine madness. Genuine madness. Director/ringmaster Francis Ford Coppola infamously said of the production, "My film is not a movie. My film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam", and this is more or less what he meant: the creation of the film was an exercise in Americans with too damn much money going into the jungle, losing their minds, and turning out something awfully close to a disaster. And yet good enough to be the only film to ever win the Palme d'Or at Cannes in 1979 despite not being finished when it screened there. It's a film that wears the scars of its production on its body: star Martin Sheen's miserable grappling with personal demons and Marlon Brando's rambling, dictatorial refusal to do anything the director asked of him directly map onto the characters they're playing, and the sense of things spinning out of control as the movie starts to shed narrative cohesion and well-defined continuity more or less precisely described the actual process of a shot that engorged itself from six weeks to sixteen months, resulted in multiple heart attacks, and more or less required the filmmakers to actually re-stage a war in the Philippines, while that country was wracked with violent political tensions.

I'll not go into the production history at too much greater length, in part because Apocalypse Now happens to have been served with one of the all-time best making-of documentaries in cinema history, the 1991 Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse, which is just as essential viewing as Apocalypse Now itself (I myself first saw the documentary before I had ever seen the feature, for what it's worth), and almost certainly a cleaner, more articulate version of the same basic story: people go into the jungle with straightforward plans, completely lose their minds as a result. It is a sublime coincidence that this is the exact same plot as the other candidate for all-time best making-of documentary, Les Blank's Burden of Dreams, about Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo. It occurs to me that if you had a full day and wanted to utterly exhausted at the end of it, you could hardly program a better quadruple feature.

The point being, anyway, if you want to see the story that Apocalypse Now tells, told with utmost clarity and jaw-dropping true stories about people rushing to the brink of insanity, you should watch Hearts of Darkness. If you want to watch the hallucinatory fever dream version of the story, just stick with Apocalypse Now itself. That's not to say that one is better than the other; the fact is, I have never once watched Apocalypse Now and at the end of it thought to myself, "what a wholly satisfying experience about which I have no significant reservations". Quite the contrary, the film is an astounding fucking mess: it took three credited editors - Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Walter Murch - almost three years to tame Coppola's swirling vortex of footage into a two-and-a-half hour object that could be satisfactorily released as a feature (22 years later, Coppola and Murch returned to rework it and add several sequences as Apocalypse Now Redux, a re-edit that I mostly oppose; to me, the ideal cut of the film is the 1979 70mm version that includes neither opening nor closing credits, with the plantation scene re-instituted in Redux but none of its other changes. Ah well, can't have everything). And what they came up with starts to disintegrate anyway, leading to a film that rivals only Easy Rider, its exact counterpart from 1969 (they are to my mind the first and last films of the "pure" New Hollywood Cinema), for encoding in its very form the unhinged derangement of the actions it depicts. And like Easy Rider, I find it supremely off-putting and indulgent and disorienting to the point of nausea. But I suppose I should talk about the beginning of the movie before the ending.

In its final form, which took most of a decade to write, and passed through the hands of John Milius and George Lucas before Coppola finally took on directorial duties, Apocalypse Now is an adaptation of Joseph Conrad's 1899 Heart of Darkness, though Conrad's work has been so thoroughly reconceived and in some important ways directly inverted that it's probably fair that the novel wasn't credited as a source. The basic throughline is the same, though: in 1969 (never explicitly stated, but easily identified thanks to a news story about the Tate murders) a drunken, spiritually desolate U.S. Army Captain, Benjamin Willard (Sheen) is given orders to travel downriver until he finds the compound where Colonel Walter Kurtz (Brando) has established a cult of some sort or another, ruling over a native tribe as a demi-god. Willard's journey into the Vietnam jungle reveals to him the complete absence of morality or immorality in the nihilistic vacuum of war. By the time Willard and what's left of his PBR crew arrive at Kurtz's compound, the captain barely resembles a functioning member of the U.S. military any more than his messianic quarry.

The film breaks fairly clearly into four unequal parts sprinkled between three acts: the mission prep, the first half of the journey that mostly involves Willard's encounter with the gung-ho surfing psychopath Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) - amazingly, "Kilgore" is the subtler name for the character, replacing "Carnage" - the second half of the journey, in which we see a USO show that resembles a sequence from The Pilgrim's Progress more than anything, as the PBR crew starts dying horribly, and then last, the surrealistic events at Kurtz's compound. The aesthetic dissimilarities between the acts are so complete that it genuinely feels like we're watching three wholly unique movies, though it is the case that the film generally evolves as it goes along: that is, the middle section, the longest and best part of the movie, gradually moves towards the misty, opaque horror of the final act, after starting off in essentially the same banal everyday style of the opening sequences (and I suppose I should excuse the very first scene from that consideration: it is neither banal nor everyday, but an exemplary mood piece carried off by The Doors' droning, apocalyptic "The End", and some fucking beautiful dissolves and straight cuts that feel like a plunge into the throes of a powerful drunken rager - Sheen's or Willard's, I can't say).

This strong division into segments is very much in line with the film's express themes and intentions, which are to depict a descent into hell. It does not do this entirely in the "right" order, though surely none of us would shift things around. The idyll with Kilgore, who turns a coastal village into a wasteland of napalm to that he can go surfing, feels like an oddly sudden escalation in all ways. The famous thing about this sequence, of course, is the heaving vocals of the "Walkürenritt" motif from Wagner's Die Walküre (surely better known to English-speakers as "Ride of the Valkyries"), played as diegetic music by Kilgore to... pump himself and his mean up? Put terror into the souls of the Vietnamese? The real answer, of course, is to provide Coppola with a a suitably grandiose aural landscape as he depicts the countryside being torn to hell in amazing aerial vistas that later give way to fire-wreathed long shots that stand Willard, quite dazed, in the remains of what was once a place and has now become Hell on Earth. As with so much of Apocalypse Now, the place where opposition to the arbitrary violence of war ends and the celebration of war as a massive-scale spectacle begins is quite impossible to pinpoint; one gets the strong impression that the filmmakers were too buried in the scale of what they were up to, to stop and think about the morality of it. The film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam.

It's almost certainly the most viscerally-involving extended sequence in the movie, so why not move it later? Simply, because it's a mere primer: it's not actually about anything. Snip it out and the plot is unchanged. It is the exaggerated, over-the-top depiction of war-as-event that prepares us to see much smaller-scale violence and atrocities meted out in a much more intimate setting, the same way that a Broadway musical leads with one of its biggest numbers. And sure enough, the second half of the river sequence is damned powerful, as we see the crew members - "Chef" Hicks (Frederic Forrest), Chief Petty Officer Phillips (Albert Hall), Lance Johnson (Sam Bottoms), "Mr. Clean" Miller (Laurence Fishburne, young enough to be going under "Larry" still) - caught up in Willard's mythic drive towards death. There are squirrely, vaguely funny scenes; there are horrifying scenes; there are unbearably sad scenes, like the one that trains the camera on one character's face as he stares at another character's dead body, while a sweet, homey letter is read placidly on the soundtrack.

Capturing all of this is one of the best-shot American films of the '70s, augmented by one of the best sound mixes ever: Murch was responsible for the soundscape as well, and it's fair to say that what he achieved redefined what sound in movies could in fact be (Apocalypse Now, following Star Wars, is one of the defining films in the establishment of 5.1 surround sound as a technical and artistic tool). The all-encompassing sounds of war and the jungle, flailing about space before and behind us, is awe-inspiring, putting Apocalypse Now in the holy trinity of great films about the sound of war, alongside All Quiet on the Western Front and Saving Private Ryan, and it is probably the most impressive achievement of them all, if only for how it also incorporates Carmine Coppola's aggressively toneless, violently synthetic music as a kind of aural wall. It sounds so utterly great that you can overlook how this is one of the greatest-looking films in the career of the genius cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, shifting with brute force from relatively natural settings to shocking fields of practically monochrome war zones: yellow combat, icy blue jungles, orange sunsets that irradiate the landscape in nuclear holocaust. And, then he pulls out an entirely new basket of tricks in the final act, often using just a solitary key light to draw as much emphasis to the deadly blackness that he's interrupting with slices of lighting. It's a flawless visual depiction of the world as a toxic, expressionist fun house, beautiful and ugly.

Anyway, how about that ending? I will confess that my exhaustion with it is inextricable with my general antipathy towards Brando, who I regard as the single most over-appreciated artist in American cinema. Even if that weren't the case, there's no real argument that Apocalypse Now finds him at his best: showing up on set have having exploded into obesity and totally disinterested in learning his lines or even the plot of the movie, he required the entire project to be re-formed around him - Storaro's amazing nighttime photography is in part an attempt to show the least amount of Brando as can be gotten away with, in the hope of suggesting a hulking muscular brute rather than a fat actor (this does not work). Most of his dialogue consists of meandering philosophical and poetic discursions, chasing stream-of-consciousness rabbits where they'll take him. It's bracing and unexpected, to be sure; but it is, for me at least, even more grotesque and annoying. Whispered, over-dramatic lines of dialogue aren't the film's strong suit - it suffers throughout from Willard's breathy, reflective voice-over, written by Michael Herr, and Brando's musings are like an even more intrusive version of that voice-over.

It's where the film breaks: Apocalypse Now is in large part a film about how its director could not keep control, and Brando's arrival on set is where Coppola finally lost the movie once and for all. It's fascinating, by all means, but it's also the most sordid, indulgent kind of filmmaking imaginable, emblematic of the dark side of New Hollywood filmmaking, in which filmmakers allow their films to collapse just for the organic beauty of it. Easy Rider had its drug fantasia that's so boldly unattractive and shrill that you kind of have to admire its commitment to anti-narrative savagery. A year after Apocalypse Now opened, Michael Cimino would chase this kind of purposefully formless aesthetic into the mega-bomb Heaven's Gate, thereby killing the New Hollywood ethos off completely, and I am painfully in love with the film. Apocalypse Now, for its part, is one of the all-time glorious messes: even more than in Easy Rider, it becomes largely impossible to parse, except in general terms, what's happening and how space is laid out, and instead the concluding action plays out asa series of fragments of actions stitched together by Eisensteinian editing techniques and the logic of whatever horrible dreams the filmmakers suffered out their in the jungle. As much as I can't stand the film for staging the brutal slaughter of a water buffalo for a symbolic point (contra Coppola's claims that he simply filmed a ritual already taking place), there's a certain rightness to it: the wantonness, the excessive, the feeling of destruction for the sake of destruction is exactly in line with everything else in the last act, where meaning itself seems to fall apart in favor of striking images and intense actions that follow intuitively rather than logically.

I invariably feel drained and unsatisfied when this part of the movie ends; I can't really complain, since there seems no reason in the world to assume that Apocalypse Now gives a shit about whether I or anybody is satisfied. It is a film about losing your mind and your self to the savage madness of the world: Vietnam in 1969 is the case study, but the film obviously has something more cosmic in mind than that. Anyway, it is well and right that the film itself should break down into meaninglessness, an all-time supreme example of form and content intimately speaking to each other to create theme. I don't have to like it, and I frankly have never decided if the final 40 minutes aren't so acutely disordered, indulgent, and tediously beholden to all of Brando's very worst habits that they make Apocalypse Now, as a whole, a "bad movie". Who gives a shit. Good or bad, success or failure, this is a magnificent, gonzo piece of cinema, and the art form would be far lesser if it had never existed.

Act I: 7/10

Act II: 10/10

Act III: 5/10

Cinematography: 10/10

Editing: 8/10

Score: 8/10

Sound Mix: 11/10

Marlon Brando: ?/10

The Vietnam War: 2/10