July of Blood: I am become Death

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, from 1986, is the filmmaking equivalent to being shot in the gut and kicked into a pool of sewage to bleed out. That's not a pullquote you should hope to see on any future home video releases, but I mean it in the most earnest, admiring way possible. There are horror movies whose nihilistic extravagance is such that you half feel that that the filmmakers are just con artists even when it's possible (as it's frequently not) to mount some kind of artistic defense of that nihilism. This is not true of Henry - indeed, calling it a horror movie of any kind is reductive and possibly outright wrong. If there was ever a movie whose entire purpose was to make the audience feel completely awful about human beings without any catharsis or the tiniest whisper of hope that would make me feel completely confident in tossing out the judgment "oh yeah, this is capital-G Great Cinema, no two ways about it", this is the one.

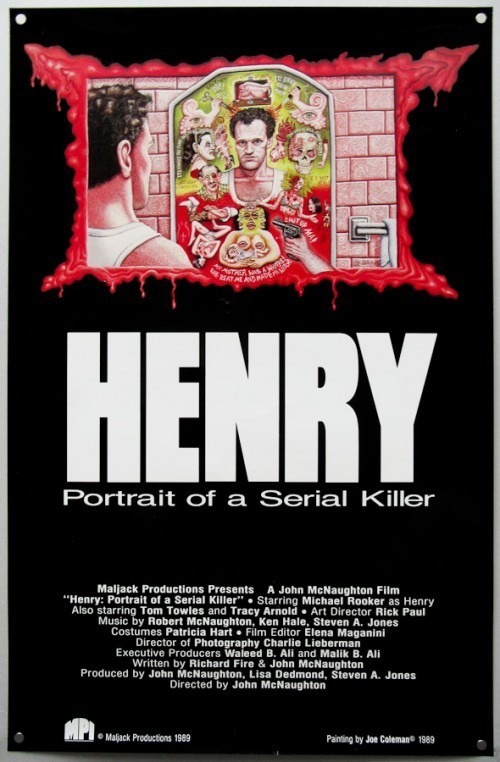

Directly but unofficially based on the life of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, Henry is a film in which almost nothing happens. Henry (Michael Rooker) needs a place to stay, so he falls in with his old prison buddy Otis (Tom Towles), right at the same time that Otis's sister Becky (Tracy Arnold) has come to stay. Before and during his time with Otis, Henry kills a whole shitload of people, and eventually Otis joins in the fun. If it is possible for Henry to feel anything remotely like the emotion that people like you and I describe as "love", he starts feeling it for Becky. Thus do 83 minutes pass by.

The film's limited scope can be at least partially explained by recourse to its production circumstances. It was made for pocket change by a borderline-amateur director named John McNaughton, who had previously made only a single film a documentary about Chicago gangsters during Prohibition. The producers planned to have him follow this relatively successful project with another documentary that fell through; with the money already lined up, they asked him to make a horror movie instead (the slasher boom was just barely still hanging on, which I imagine was a major influence on everybody's decision-making process). Henry is what he and co-writer Richard Fire came up with to maximise the microscopic budget: a film with very few speaking parts, no action, and many primitive gore effects, in which we virtually only ever see the aftermath of murder, not the murders themselves. It takes place in completely unadorned locations shot on the fly, captured with an extreme realism that's as much an accident as anything. There's not a molecule of polish or style in Charlie Lieberman's cinematography, just grainy footage apparently lit using available light, heavily reliant on long takes and wide shots. For the most part it doesn't even seem to have been color-corrected.

This is a wholly artless film. That's not a criticism. Artlessness is the heart and soul of what makes Henry so entirely successful: it's rawness offers no comfort or artistic gloss that separates us from the ugliness of the content. The acting is a major contributor to this, with most of the cast giving what are, by any objective measure, terrible performances. Towles and Arnold emphasise lines weirdly, put no effort into their expressions and body language, and mostly don't give the impression of having put any thought into how their characters feel about anything, though both of them have individual moments: Otis's shocked expression when Henry kills two women right in front of him is almost comically unexpected and adds a great deal of impact to the moment; Arnold makes good use of some tight close-ups in the film's back half, as her character grows more distraught with a life that's not going right. But these moments are outliers

Rooker, though, now there's a performance for the ages. It's incredibly limited, small acting, mostly consisting of emptying himself of all overt affect; at a glance, it appears to be more of the same blank, amateur acting of the rest of the movie. But the more time we spend with him, and the more we listen to his chilly, banal line readings and lack of movement, the harder it is to think that way. This isn't the unmodulated work of someone who hasn't figured out what they're doing, like Rooker's co-stars; this is clamped-down and deliberately inhuman, stripping everything warm or relatable out of the character, flattening out his voice, leaving nothing for us to recognise or respond to. It is one of the most legitimately terrifying performances of a serial killer in all of cinema: there's no obvious villainy, no hamminess, no menace, no cruelty. There's only a blank, a complete void behind Rooker's eyes and indifferently handsome features. I think that it could only work so well in a context like this: drop Rooker's exact same performance in a proper movie with lots of retakes and careful character building everywhere else, and I think he'd just seem wildly out-of-place, with it verging on farce to imagine that he'd be able to spend thirty seconds in polite company without immediately figuring out that something's enormously wrong inside his head. In these primitive surroundings, Rooker has a chance to sneak up and surprise us: he's using the very artlessness of the film to hide in plain sight, getting much closer to the viewer before springing the abyssal horror of his character upon us.

The aesthetic simplicity of the film works in a much more direct manner: Henry depicts a squalid world and does so without putting any filter on it (other than its leading, somewhat annoying score, and a few ingenious moments with animalistic sound effects driving home the impact of a killing). The whole movie, with its found locations and lack of narrative drive, gives us an incredibly vivid snapshot of everyday life in the presence of someone like Henry. And even, in a few deeply unnerving moments, inside his very head: his casual discussion with Otis of the strategies one must employ to keep ahead of the police and continue one's murder spree is among the most chilling scenes in all of serial killer cinema, banishing any sense that we are watching an irrational man. We are watching a profoundly rational man - rational to the point he has lost everything else, maybe. It feels like what happens when you ask a documentarian to switch gears and make a horror picture: it is based in journalistic observation of how spaces are laid out and how people life in those spaces, and it tries to capture the essence of its killer by simply following and watching what he does in the slow moments where nothing happens. The film's depiction of its world is disturbingly casual and everyday: average houses in average neighborhoods, loud-mouthed Chicago blue-collar folks hanging around, dirty city streets and generic mall facades leftover from the 1970s. The film adds nothing to the real world because it cannot afford to; it simply has to set its action in places that actually exist and see what happens.

It's hard to imagine any narrative film being more entirely naturalistic than this; it's basically neorealism dusted off and applied to a serial killer biopic. That might have been a necessary choice, but it's an inspired one: I can't name any other film about such a killer that is so attentive to the fact that men like Henry actually exist in the real world, ripping at the basic sense of shared humanity and common decency that underpin all of civilisation. It is ultimately too good at demonstrating how completely alien and unknowable Henry is to mount any real argument as to how such men can exist, but in all other ways, this is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking: as sober-minded an examination of how killers exist in the world as has ever been made, and probably as can ever be conceptually mounted. It's a powerful, disgusting, despiriting work of art, too serious to qualify as horror, too smart to be exploitation. It is unspeakably unpleasant, and it is almost perfect.

Body Count: A rather extravagant 14, plus 2 that are heavily implied, but we never as-such see the bodies. Note that the frequency of killings decreases towards the end, which is exactly the opposite as we'd expect to see from a slasher film or other standard-issue body count picture.

Directly but unofficially based on the life of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, Henry is a film in which almost nothing happens. Henry (Michael Rooker) needs a place to stay, so he falls in with his old prison buddy Otis (Tom Towles), right at the same time that Otis's sister Becky (Tracy Arnold) has come to stay. Before and during his time with Otis, Henry kills a whole shitload of people, and eventually Otis joins in the fun. If it is possible for Henry to feel anything remotely like the emotion that people like you and I describe as "love", he starts feeling it for Becky. Thus do 83 minutes pass by.

The film's limited scope can be at least partially explained by recourse to its production circumstances. It was made for pocket change by a borderline-amateur director named John McNaughton, who had previously made only a single film a documentary about Chicago gangsters during Prohibition. The producers planned to have him follow this relatively successful project with another documentary that fell through; with the money already lined up, they asked him to make a horror movie instead (the slasher boom was just barely still hanging on, which I imagine was a major influence on everybody's decision-making process). Henry is what he and co-writer Richard Fire came up with to maximise the microscopic budget: a film with very few speaking parts, no action, and many primitive gore effects, in which we virtually only ever see the aftermath of murder, not the murders themselves. It takes place in completely unadorned locations shot on the fly, captured with an extreme realism that's as much an accident as anything. There's not a molecule of polish or style in Charlie Lieberman's cinematography, just grainy footage apparently lit using available light, heavily reliant on long takes and wide shots. For the most part it doesn't even seem to have been color-corrected.

This is a wholly artless film. That's not a criticism. Artlessness is the heart and soul of what makes Henry so entirely successful: it's rawness offers no comfort or artistic gloss that separates us from the ugliness of the content. The acting is a major contributor to this, with most of the cast giving what are, by any objective measure, terrible performances. Towles and Arnold emphasise lines weirdly, put no effort into their expressions and body language, and mostly don't give the impression of having put any thought into how their characters feel about anything, though both of them have individual moments: Otis's shocked expression when Henry kills two women right in front of him is almost comically unexpected and adds a great deal of impact to the moment; Arnold makes good use of some tight close-ups in the film's back half, as her character grows more distraught with a life that's not going right. But these moments are outliers

Rooker, though, now there's a performance for the ages. It's incredibly limited, small acting, mostly consisting of emptying himself of all overt affect; at a glance, it appears to be more of the same blank, amateur acting of the rest of the movie. But the more time we spend with him, and the more we listen to his chilly, banal line readings and lack of movement, the harder it is to think that way. This isn't the unmodulated work of someone who hasn't figured out what they're doing, like Rooker's co-stars; this is clamped-down and deliberately inhuman, stripping everything warm or relatable out of the character, flattening out his voice, leaving nothing for us to recognise or respond to. It is one of the most legitimately terrifying performances of a serial killer in all of cinema: there's no obvious villainy, no hamminess, no menace, no cruelty. There's only a blank, a complete void behind Rooker's eyes and indifferently handsome features. I think that it could only work so well in a context like this: drop Rooker's exact same performance in a proper movie with lots of retakes and careful character building everywhere else, and I think he'd just seem wildly out-of-place, with it verging on farce to imagine that he'd be able to spend thirty seconds in polite company without immediately figuring out that something's enormously wrong inside his head. In these primitive surroundings, Rooker has a chance to sneak up and surprise us: he's using the very artlessness of the film to hide in plain sight, getting much closer to the viewer before springing the abyssal horror of his character upon us.

The aesthetic simplicity of the film works in a much more direct manner: Henry depicts a squalid world and does so without putting any filter on it (other than its leading, somewhat annoying score, and a few ingenious moments with animalistic sound effects driving home the impact of a killing). The whole movie, with its found locations and lack of narrative drive, gives us an incredibly vivid snapshot of everyday life in the presence of someone like Henry. And even, in a few deeply unnerving moments, inside his very head: his casual discussion with Otis of the strategies one must employ to keep ahead of the police and continue one's murder spree is among the most chilling scenes in all of serial killer cinema, banishing any sense that we are watching an irrational man. We are watching a profoundly rational man - rational to the point he has lost everything else, maybe. It feels like what happens when you ask a documentarian to switch gears and make a horror picture: it is based in journalistic observation of how spaces are laid out and how people life in those spaces, and it tries to capture the essence of its killer by simply following and watching what he does in the slow moments where nothing happens. The film's depiction of its world is disturbingly casual and everyday: average houses in average neighborhoods, loud-mouthed Chicago blue-collar folks hanging around, dirty city streets and generic mall facades leftover from the 1970s. The film adds nothing to the real world because it cannot afford to; it simply has to set its action in places that actually exist and see what happens.

It's hard to imagine any narrative film being more entirely naturalistic than this; it's basically neorealism dusted off and applied to a serial killer biopic. That might have been a necessary choice, but it's an inspired one: I can't name any other film about such a killer that is so attentive to the fact that men like Henry actually exist in the real world, ripping at the basic sense of shared humanity and common decency that underpin all of civilisation. It is ultimately too good at demonstrating how completely alien and unknowable Henry is to mount any real argument as to how such men can exist, but in all other ways, this is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking: as sober-minded an examination of how killers exist in the world as has ever been made, and probably as can ever be conceptually mounted. It's a powerful, disgusting, despiriting work of art, too serious to qualify as horror, too smart to be exploitation. It is unspeakably unpleasant, and it is almost perfect.

Body Count: A rather extravagant 14, plus 2 that are heavily implied, but we never as-such see the bodies. Note that the frequency of killings decreases towards the end, which is exactly the opposite as we'd expect to see from a slasher film or other standard-issue body count picture.