Collateral damage

A War is not two films dwelling one films' body, not exactly. It is one very sleekly unified film divided into two obviously distinct phases, and you can identify the exact frame where the second one starts. And that wouldn't really be worth leaning on that, except that the first phase is a very well-made version of something that's really not at all interesting, whereas the second phase is a very well-made version of something that's quite interesting. But without the first half being exactly it's not at all interesting self, the second half couldn't exist. So what is the critic to do with this situation? Talking about all of the best stuff puts us pretty firmly in spoiler territory. So, y'know, keep that in mind as we move forward.

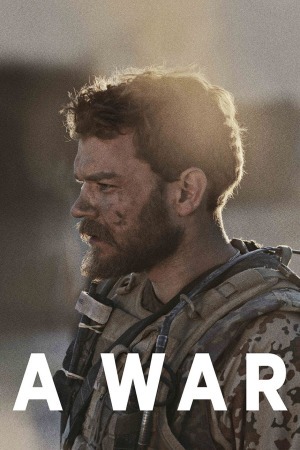

The war that is A War is the International Security Assistance Force, the NATO-let military mission responsible, basically, for cleaning up America's messes in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2014. In one tiny corner of that beleaguered country, we meet a team of Danish soldiers under the command of Claus Michael Pedersen (Pilou Asbæk), a decent fellow beloved by his men and looked to with affection by the local Afghani people he's charged with protecting. Back in Denmark, Claus's wife Maria (Tuva Novotny) is having a fairly miserable time being a temporarily single mother to their three children, exacerbated by how troubling the lack of a present father figure is to Julius (Adam Chessa), the kid in the middle, right at the age when kids start to have enough self-awareness to be capable of resenting their parents.

The film dances between these two geographically disparate but emotionally-linked subplots for a bit more than half of its 115-minute running time, and it's not great. You can kind of tell what director Tobias Lindholm and editor Adam Nielsen were aiming at: showing us the actual family that Claus left behind for a year to explain why he'd become so caring and protective to the surrogate family he's fashioned out of the men he leads. The problem - problem's a funny word for it - is that the Denmark scenes are too good: Novotny gives an exceptionally considered, detailed performance of an unabashed stock type (the harried mother keeping things together by force of will, loving her children but slightly hating them through all the love because why must they make everything so hard), and Lindholm's script creates specific crises for Maria to cope with that still have the tang of the universal. The homefront storyline is just as vivid and meaningful as the Afghanistan story, and that's in theory just as it should be, except: Maria's story informs Claus's, but Claus's story doesn't inform Maria's. And so the whole balance of the thing gets twisted about and feels massively unsatisfying. That's one of the big problems.

The other big problem is that, I'm sorry, this is old news. Lindholm's last feature, A Hijacking, utilised an entirely generic aesthetic program, so common in Europan art cinema that I imagine it comes as a preset on their cameras: ugly overlighting, jittery handheld camera work, a limited and modestly desaturated color palette. Add in the scenes where nothing much happens but we're allowed to develop a clear sense of how the major characters fit into their worlds, and you have the entirety of his style - but, the story of A Hijacking> is so starkly unique that it felt fresh and gripping nonetheless. A War uses precisely the same style, but in the first half, and especially in the Afghanistan scenes, its plot pure boilerplate. Sandy-colored desert warfare scenes, showcasing how the well-intentioned Europeans who nevertheless clearly don't belong there try to fight through their endless fatigue with this damned war on terror and the ad hoc ingenuity of their opponents, while being so technically advanced that they can be casual and buddy-buddy and lack the raw nerves of the hell-on-earth battlefields of the 20th Century - this is as unoriginal as the aesthetic, and they complement each other for a distinct, and highly deflating textbook example of How To Make A War Film About Afghanistan/Iraq. That's the other big problem, and the more damaging one.

At a certain point, Claus's men get pinned down by a Taliban force, and one man in particular, "Lasse" Hassan (Dulfi Al-Jabouri) is surely doomed unless Claus orders an airstrike right now. Except that neither he nor any of his men can be confident where the enemy fighters are standing, and there are very clear rules of engagement. Claus breaks those rules to save Lasse's life, and the net result is zero dead Taliban fighters and eleven dead civilians, more than half of them children.

And it is just after this certain point that A War becomes absolutely splendid and so freakishly gripping that I would have sworn under oath that the last 45 minutes of the movie only lasted about 15. Again, there's not getting here without laying the tracks in the first hour - it is precisely that Claus is just one random commander of one random company out in the hinterlands of Afghanistan that matters, and it's precisely by using all of the standard tropes of its genre that A War can make that point. But it doesn't make that hour and less bland.

Where we go, though, is wonderful, a perfect successor to A Hijacking and its sterling exploration of the way that people negotiate around hard decisions and in accordance to their own sense of right and wrong. A War turns into something very much like Dostoevsky, as Maria's desperation to keep her husband by her side and not in military prison leads her to beg him to make a decision that he knows is wrong, and that he cannot possibly un-make. Then follows a perverse courtroom thriller, in which the audience's Pavlovian desire for an emotionally satisfying verdict is turned inside out, and it becomes more or less impossible to say what the emotionally satisfying verdict is: the one that leaves Claus aware for the rest of his life that he is an evil man? Surely it can't be that, but that's the one our training as movie viewers asks us to root for.

Asbæk is extraordinary in these scenes, a bundle of tense, scared misery and self-hatred, barely able to move his facial muscles but communicating through his tired eyes everything we need (Novotny recedes into reaction shots in the second hour, sadly). Lindholm and cinematographer Magnus Nordenhof Jønck start to embrace a pattern of close-ups, virtually never showing two characters in the same frame, and often showing us a character listening in lieu of a character speaking: it is a great aesthetic for putting psychological interiority on the screen, and since A War is at this point juggling both abstract moral & legal questions as well as the highly personal question of a guilty conscience, interiority is just what it needs.

You could hardly hope to improve on this: it's an intellectually stimulating game of "could you make the ethical choice? And are you certain which choice is ethical?" that acknowledges human fraility and sympathises with it, but does not excuse it as a "get out of jail free card". It's not all perfect - for one thing, I'd give a whole lot for the final shot to be put on a goddamn tripod - but it's pretty damn extraordinary. Does it justify the logy first half? Obviously, the first half is still competently-made and all, and I'm sure plenty of viewers wouldn't even have any problems with it to begin with. Still and all, for me this feels a little bit too much like working your way through a big plate of overcooked, flavorless vegetables on the way to a top-notch dessert.

The war that is A War is the International Security Assistance Force, the NATO-let military mission responsible, basically, for cleaning up America's messes in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2014. In one tiny corner of that beleaguered country, we meet a team of Danish soldiers under the command of Claus Michael Pedersen (Pilou Asbæk), a decent fellow beloved by his men and looked to with affection by the local Afghani people he's charged with protecting. Back in Denmark, Claus's wife Maria (Tuva Novotny) is having a fairly miserable time being a temporarily single mother to their three children, exacerbated by how troubling the lack of a present father figure is to Julius (Adam Chessa), the kid in the middle, right at the age when kids start to have enough self-awareness to be capable of resenting their parents.

The film dances between these two geographically disparate but emotionally-linked subplots for a bit more than half of its 115-minute running time, and it's not great. You can kind of tell what director Tobias Lindholm and editor Adam Nielsen were aiming at: showing us the actual family that Claus left behind for a year to explain why he'd become so caring and protective to the surrogate family he's fashioned out of the men he leads. The problem - problem's a funny word for it - is that the Denmark scenes are too good: Novotny gives an exceptionally considered, detailed performance of an unabashed stock type (the harried mother keeping things together by force of will, loving her children but slightly hating them through all the love because why must they make everything so hard), and Lindholm's script creates specific crises for Maria to cope with that still have the tang of the universal. The homefront storyline is just as vivid and meaningful as the Afghanistan story, and that's in theory just as it should be, except: Maria's story informs Claus's, but Claus's story doesn't inform Maria's. And so the whole balance of the thing gets twisted about and feels massively unsatisfying. That's one of the big problems.

The other big problem is that, I'm sorry, this is old news. Lindholm's last feature, A Hijacking, utilised an entirely generic aesthetic program, so common in Europan art cinema that I imagine it comes as a preset on their cameras: ugly overlighting, jittery handheld camera work, a limited and modestly desaturated color palette. Add in the scenes where nothing much happens but we're allowed to develop a clear sense of how the major characters fit into their worlds, and you have the entirety of his style - but, the story of A Hijacking> is so starkly unique that it felt fresh and gripping nonetheless. A War uses precisely the same style, but in the first half, and especially in the Afghanistan scenes, its plot pure boilerplate. Sandy-colored desert warfare scenes, showcasing how the well-intentioned Europeans who nevertheless clearly don't belong there try to fight through their endless fatigue with this damned war on terror and the ad hoc ingenuity of their opponents, while being so technically advanced that they can be casual and buddy-buddy and lack the raw nerves of the hell-on-earth battlefields of the 20th Century - this is as unoriginal as the aesthetic, and they complement each other for a distinct, and highly deflating textbook example of How To Make A War Film About Afghanistan/Iraq. That's the other big problem, and the more damaging one.

At a certain point, Claus's men get pinned down by a Taliban force, and one man in particular, "Lasse" Hassan (Dulfi Al-Jabouri) is surely doomed unless Claus orders an airstrike right now. Except that neither he nor any of his men can be confident where the enemy fighters are standing, and there are very clear rules of engagement. Claus breaks those rules to save Lasse's life, and the net result is zero dead Taliban fighters and eleven dead civilians, more than half of them children.

And it is just after this certain point that A War becomes absolutely splendid and so freakishly gripping that I would have sworn under oath that the last 45 minutes of the movie only lasted about 15. Again, there's not getting here without laying the tracks in the first hour - it is precisely that Claus is just one random commander of one random company out in the hinterlands of Afghanistan that matters, and it's precisely by using all of the standard tropes of its genre that A War can make that point. But it doesn't make that hour and less bland.

Where we go, though, is wonderful, a perfect successor to A Hijacking and its sterling exploration of the way that people negotiate around hard decisions and in accordance to their own sense of right and wrong. A War turns into something very much like Dostoevsky, as Maria's desperation to keep her husband by her side and not in military prison leads her to beg him to make a decision that he knows is wrong, and that he cannot possibly un-make. Then follows a perverse courtroom thriller, in which the audience's Pavlovian desire for an emotionally satisfying verdict is turned inside out, and it becomes more or less impossible to say what the emotionally satisfying verdict is: the one that leaves Claus aware for the rest of his life that he is an evil man? Surely it can't be that, but that's the one our training as movie viewers asks us to root for.

Asbæk is extraordinary in these scenes, a bundle of tense, scared misery and self-hatred, barely able to move his facial muscles but communicating through his tired eyes everything we need (Novotny recedes into reaction shots in the second hour, sadly). Lindholm and cinematographer Magnus Nordenhof Jønck start to embrace a pattern of close-ups, virtually never showing two characters in the same frame, and often showing us a character listening in lieu of a character speaking: it is a great aesthetic for putting psychological interiority on the screen, and since A War is at this point juggling both abstract moral & legal questions as well as the highly personal question of a guilty conscience, interiority is just what it needs.

You could hardly hope to improve on this: it's an intellectually stimulating game of "could you make the ethical choice? And are you certain which choice is ethical?" that acknowledges human fraility and sympathises with it, but does not excuse it as a "get out of jail free card". It's not all perfect - for one thing, I'd give a whole lot for the final shot to be put on a goddamn tripod - but it's pretty damn extraordinary. Does it justify the logy first half? Obviously, the first half is still competently-made and all, and I'm sure plenty of viewers wouldn't even have any problems with it to begin with. Still and all, for me this feels a little bit too much like working your way through a big plate of overcooked, flavorless vegetables on the way to a top-notch dessert.

Categories: scandinavian cinema, war pictures