You know you can follow my voice

A review requested by theizz, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

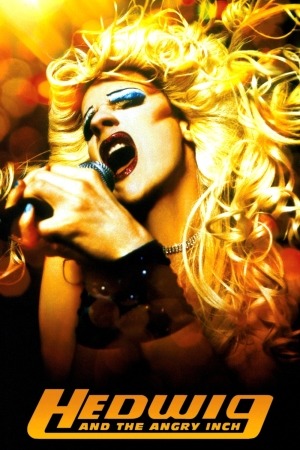

Upon revisiting the great musical character dramedy Hedwig and the Angry Inch for the first time in many years, I was pleased and more than a little bit surprised to find that I treasured it more now than I did even when it stormed to Earth like one of Zeus's thunderbolts in 2001. The patina of nostalgia undoubtedly has something to do with that. For although Hedwig remains outstandingly fresh and energetic after 15 years,* both stylistically and thematically, it's also an especially splendid example of the kind of movie that in '01 had grown a bit old-hat even when it was working this well (and I speak for nobody but myself), the socially radical American Indie picture playing around in a genre sandbox. Oh! how it seemed in those days that the great independent boom of the 1990s was just going to last forever. We still have indies, of course, but they are more cautious and far too reflexively realist. Hedwig swaggers like a motherfucker - the special, one-of-a-kind indie swagger, that you just don't get much of anymore.

Hedwig and the Angry Inch, even by the standards of its day, is a bold and brazen thing. It is the story of a genderqueer glam rock star named Hedwig (John Cameron Mitchell, who also directs), born a boy named Hansel in East Berlin right at the time the Berlin Wall was being constructed. After a botched sex-reassignment operation that left her with a vestigial stub of a former penis and no functioning genitalia, Hedwig married an American GI who left her the same day that the Wall was torn down. Following this, Hedwig scraped through the 1990s, forming a band and falling in love with a right-wing Christian teen whom she molded into an alt-rock star before he abandoned her and stole her music for his own career.

All of this, mind you, is the backstory of the movie, which goes a little bit of the way to suggesting how busy and active Hedwig is. But let's not rush through it. For this is, by any stretch of the imagination, radically transgressive, in a way that very movies in the LGBTQ arena really try to be. It is about identity politics in a uniquely active way: the entire plot and most of the individual beats within it focus on the way that identity is partially innate, partially constructed by experiences, and also how identity is always essentially provisional. And this is not just a matter of identity at the level of gender: finding a source of self-identity in one's profession is hugely important in the film as well, and the idea of nationalism enters the film even before the idea of queerness does. Hedwig is essentially a stateless person, a genderless person, and an unsuccessful music star, and this what gives the film - driven by boisterous rock songs and a snide sense of humor - a lingering tragic dimension.

What's really amazing about Hedwig, in my eyes, is that all of this playing around with the idea of identity as contingent and alterable, its depiction of nonbinary gender norms, and its equivalence of personal trauma with national crisis - none of this is presented with any particular loudness or politicized passion. It's just assumed to be unexceptional and part of Hedwig's convoluted life. I think that's part of what makes Hedwig so very radical, is that you can watch it and respond to it without necessarily having even the smallest impression that the film is trying to present a social argument. Compare, for example, Mitchell's follow-up movie, the lumpy and much-too-literal Shortbus, which is so much about its representations of human sexuality that it forgets to be a watchable movie. Hedwig does so much that identity radicalism is a mere facet, one you don't even have to pay attention to.

For example: it is one of the best film musicals of the 21st Century, and along with Moulin Rouge! got most of the credit for bringing that genre back to life in 2001 after years in the wilderness. Frankly, I don't think either of those films has been topped ever since. In the specific case of Hedwig and the Angry Inch, we find Mitchell adapting his own book for a 1998 stage production with songs by Stephen Trask, and doing a terrific job of it: I would, in fact, put this on the vanishingly small list of cinematic adaptations of stage musicals that distinctly improve upon the material. This is mostly due to one tiny but key difference. The two shows are, generally speaking, the same: in the present tense of the late-'90s, Hedwig is putting on a show with the Angry Inch right by a theater where her thieving ex, Tommy Gnosis (Michael Pitt) is singing, and her set maps onto her life story, which she recites for the audience in between songs. The film sets her shows inside a national chain of seafood restaurants, Bilgewater's, and that one tiny shift does remarkable things to open up the material. I mean, there's actually a much bigger change: the movie incorporates flashbacks and lots of cutaway jokes, and they're incorporated such that you'd never, ever be able to tell that they weren't part of it initially. It's the old "open it up for the movies" trick, done unusually well.

And yet, I persist in being more impressed by the Bilgewater's gimmick than anything else. It adds a weird, ineffable sense of sadness to the whole affair. Central to the material is the unspoken reality that for all Hedwig's showmanship and projections of confidence, she's insecure and low-rent, outclassed in talent by her lead-guitarist and boyfriend Yitzhak (Miriam Shor - the stage version presented Yitzhak as a former drag queen, the film is much less clear on that point, but the gesture of having the masculine character played by a woman is appreciated in the overall scheme of "gender, what the fuck ever"), reduced to haunting her successful douchebag ex for any kind of relevance. Placing her show in the tacky surroundings of a crappy restaurant underlines that, and showing the business of the restaurant going on around her - along with the baffled look of the mostly elderly patrons - intensifies the film's sadness in a way. At the same time, the dowdy, pathetic surroundings only serve to make Hedwig's triumphant, high-energy musical performances that much more exciting and vital, since there's so much stronger of a sense of overcoming the worst possible odds.

By all means, the musical numbers are critical to the film. It is densely packed with them - eleven songs in 92 minutes - and while none of them are book numbers (though a few of them are staged that way in the film), they serve to do most of the heavy lifting of establishing character, fleshing out backstory, and providing the story's emotional throughline. I can imagine a viewer who doesn't care about anything else in the film still loving it if they responded to the soundtrack positively enough; I cannot imagine anything close to the opposite. It's a polyglot of glam, Broadway showtunes, and rock, though I think the best summary of the score is "pop punk". Mitchell stages the numbers with keen energy and frenetic editing, nicely contrasting the ragged DIY realism of the non-musical scenes. It's a nigh-unto-perfect mixture of the stylistic excess of glam, and the heavily performative Hedwig, with the narrowly-focused psychological intimacy of the '90s indie scene.

Anyway, the songs are great (if you like that sort of thing, as I do), and greater still is how well Mitchell performs them: it's as perfect an example of acting while singing as recent musical cinema has produced, and the place where Hedwig most clearly betrays its roots as a stage musical, one where Mitchell got to hone the character for a live audience, and translate what he learned there to playing for an audience present in the film, and not scaling all the way down to a typical cinema-sized perfromance. It's staggeringly good, albeit in a very unnatural way, aided by the decision to record the songs live (clearly not in all cases, and Trask dubbed Pitt's singing voice). There's a degree of unrehearsed, ragged force in Mitchell's performance of Hedwig's performances, where the emotions she's feeling keep bleeding out through the raging songs, sometimes working against them, sometimes reinforcing them. It's a brilliant, deeply sympathetic performance that gives the apparently sarcastic, slick film so very much heart, and makes this one of the few modern movie musicals that deserves to stand alongside the classics of the genre.

Upon revisiting the great musical character dramedy Hedwig and the Angry Inch for the first time in many years, I was pleased and more than a little bit surprised to find that I treasured it more now than I did even when it stormed to Earth like one of Zeus's thunderbolts in 2001. The patina of nostalgia undoubtedly has something to do with that. For although Hedwig remains outstandingly fresh and energetic after 15 years,* both stylistically and thematically, it's also an especially splendid example of the kind of movie that in '01 had grown a bit old-hat even when it was working this well (and I speak for nobody but myself), the socially radical American Indie picture playing around in a genre sandbox. Oh! how it seemed in those days that the great independent boom of the 1990s was just going to last forever. We still have indies, of course, but they are more cautious and far too reflexively realist. Hedwig swaggers like a motherfucker - the special, one-of-a-kind indie swagger, that you just don't get much of anymore.

Hedwig and the Angry Inch, even by the standards of its day, is a bold and brazen thing. It is the story of a genderqueer glam rock star named Hedwig (John Cameron Mitchell, who also directs), born a boy named Hansel in East Berlin right at the time the Berlin Wall was being constructed. After a botched sex-reassignment operation that left her with a vestigial stub of a former penis and no functioning genitalia, Hedwig married an American GI who left her the same day that the Wall was torn down. Following this, Hedwig scraped through the 1990s, forming a band and falling in love with a right-wing Christian teen whom she molded into an alt-rock star before he abandoned her and stole her music for his own career.

All of this, mind you, is the backstory of the movie, which goes a little bit of the way to suggesting how busy and active Hedwig is. But let's not rush through it. For this is, by any stretch of the imagination, radically transgressive, in a way that very movies in the LGBTQ arena really try to be. It is about identity politics in a uniquely active way: the entire plot and most of the individual beats within it focus on the way that identity is partially innate, partially constructed by experiences, and also how identity is always essentially provisional. And this is not just a matter of identity at the level of gender: finding a source of self-identity in one's profession is hugely important in the film as well, and the idea of nationalism enters the film even before the idea of queerness does. Hedwig is essentially a stateless person, a genderless person, and an unsuccessful music star, and this what gives the film - driven by boisterous rock songs and a snide sense of humor - a lingering tragic dimension.

What's really amazing about Hedwig, in my eyes, is that all of this playing around with the idea of identity as contingent and alterable, its depiction of nonbinary gender norms, and its equivalence of personal trauma with national crisis - none of this is presented with any particular loudness or politicized passion. It's just assumed to be unexceptional and part of Hedwig's convoluted life. I think that's part of what makes Hedwig so very radical, is that you can watch it and respond to it without necessarily having even the smallest impression that the film is trying to present a social argument. Compare, for example, Mitchell's follow-up movie, the lumpy and much-too-literal Shortbus, which is so much about its representations of human sexuality that it forgets to be a watchable movie. Hedwig does so much that identity radicalism is a mere facet, one you don't even have to pay attention to.

For example: it is one of the best film musicals of the 21st Century, and along with Moulin Rouge! got most of the credit for bringing that genre back to life in 2001 after years in the wilderness. Frankly, I don't think either of those films has been topped ever since. In the specific case of Hedwig and the Angry Inch, we find Mitchell adapting his own book for a 1998 stage production with songs by Stephen Trask, and doing a terrific job of it: I would, in fact, put this on the vanishingly small list of cinematic adaptations of stage musicals that distinctly improve upon the material. This is mostly due to one tiny but key difference. The two shows are, generally speaking, the same: in the present tense of the late-'90s, Hedwig is putting on a show with the Angry Inch right by a theater where her thieving ex, Tommy Gnosis (Michael Pitt) is singing, and her set maps onto her life story, which she recites for the audience in between songs. The film sets her shows inside a national chain of seafood restaurants, Bilgewater's, and that one tiny shift does remarkable things to open up the material. I mean, there's actually a much bigger change: the movie incorporates flashbacks and lots of cutaway jokes, and they're incorporated such that you'd never, ever be able to tell that they weren't part of it initially. It's the old "open it up for the movies" trick, done unusually well.

And yet, I persist in being more impressed by the Bilgewater's gimmick than anything else. It adds a weird, ineffable sense of sadness to the whole affair. Central to the material is the unspoken reality that for all Hedwig's showmanship and projections of confidence, she's insecure and low-rent, outclassed in talent by her lead-guitarist and boyfriend Yitzhak (Miriam Shor - the stage version presented Yitzhak as a former drag queen, the film is much less clear on that point, but the gesture of having the masculine character played by a woman is appreciated in the overall scheme of "gender, what the fuck ever"), reduced to haunting her successful douchebag ex for any kind of relevance. Placing her show in the tacky surroundings of a crappy restaurant underlines that, and showing the business of the restaurant going on around her - along with the baffled look of the mostly elderly patrons - intensifies the film's sadness in a way. At the same time, the dowdy, pathetic surroundings only serve to make Hedwig's triumphant, high-energy musical performances that much more exciting and vital, since there's so much stronger of a sense of overcoming the worst possible odds.

By all means, the musical numbers are critical to the film. It is densely packed with them - eleven songs in 92 minutes - and while none of them are book numbers (though a few of them are staged that way in the film), they serve to do most of the heavy lifting of establishing character, fleshing out backstory, and providing the story's emotional throughline. I can imagine a viewer who doesn't care about anything else in the film still loving it if they responded to the soundtrack positively enough; I cannot imagine anything close to the opposite. It's a polyglot of glam, Broadway showtunes, and rock, though I think the best summary of the score is "pop punk". Mitchell stages the numbers with keen energy and frenetic editing, nicely contrasting the ragged DIY realism of the non-musical scenes. It's a nigh-unto-perfect mixture of the stylistic excess of glam, and the heavily performative Hedwig, with the narrowly-focused psychological intimacy of the '90s indie scene.

Anyway, the songs are great (if you like that sort of thing, as I do), and greater still is how well Mitchell performs them: it's as perfect an example of acting while singing as recent musical cinema has produced, and the place where Hedwig most clearly betrays its roots as a stage musical, one where Mitchell got to hone the character for a live audience, and translate what he learned there to playing for an audience present in the film, and not scaling all the way down to a typical cinema-sized perfromance. It's staggeringly good, albeit in a very unnatural way, aided by the decision to record the songs live (clearly not in all cases, and Trask dubbed Pitt's singing voice). There's a degree of unrehearsed, ragged force in Mitchell's performance of Hedwig's performances, where the emotions she's feeling keep bleeding out through the raging songs, sometimes working against them, sometimes reinforcing them. It's a brilliant, deeply sympathetic performance that gives the apparently sarcastic, slick film so very much heart, and makes this one of the few modern movie musicals that deserves to stand alongside the classics of the genre.