A review in brief

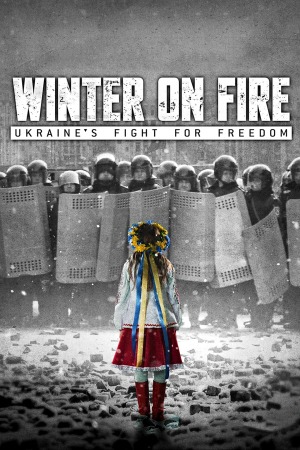

Maidan exists. This is the reality that Winter on Fire, Netflix's Oscar-nominated documentary about the February, 2014 revolution in Ukraine, has to contend with and never manages to overcome. It's an unfair thing to demand of any film that it has to live up to the standard of some other specific film, I concede, and perhaps to the viewer who'd never seen or heard of Maidan, Sergei Loznitsa's 2014 vérité-style snapshot of the situation on the ground in Ukraine would be more inclined to find Evgeny Afineevsky's take on the material to be more satisfying and intellectually stimulating than I'm able to.

Also, maybe not. Just in reference solely to itself and the material it explores, Winter on Fire is a tangibly lightweight compendium of interviews with a wide range of protesters set up in Maidan Nezalezhnosti, the famed Independence Square of Kyiv. It captures something that does make it unmistakably valuable as a snapshot of a historical moment: the righteous anger of the protesters, who felt with considerable justification that they were being sold out by their elected government, which was at that time about to reject a potential path into the Eurozone. As journalism, the act of gathering these narratives into one place is of obviously clear value.

But that's the starting point of journalism, not the end, and this is where Winter on Fire comes up miserably short. All of this is plainly meant to serve as an explanation not just of the specific feelings of a dozen or so Ukrainians, all of them indelibly captured by Afineevsky's camera (the clear standout: a little urchin boy who initially joined the protesters because of the possibility of getting medical attention. But several of the onscreen interviewees emerge with rich, interesting lives that we see around the edges); this is also a film with an eye to explaining the politics of the protests, and here the film is a complete flop. It presents a hopelessly crimped, worm's-eye-view of a very difficult international situation, one that has been treated with appallingly trivial analysis in the U.S newsmedia, at any rate, and having a glossy magazine sidebar approach to that material - let alone setting it on the path to one of cinema's most prestigious awards - is hardly good for anybody. The film's up-with-people feel-goodism is charming and pleasant and all, but it's simply not engaged with its subject in a rewarding way.

So back to Maidan. That film didn't really go into any depths that this one doesn't, but it signally lacked the pretense of doing so: it was an attempt to capture reality for a stretch of time. Winter on Fire, with its carefully assembled cast of figures, is an attempt to simplify reality, and it turns out far more superficial than its subject, along with the footage captured and assembled here, deserve.

Also, maybe not. Just in reference solely to itself and the material it explores, Winter on Fire is a tangibly lightweight compendium of interviews with a wide range of protesters set up in Maidan Nezalezhnosti, the famed Independence Square of Kyiv. It captures something that does make it unmistakably valuable as a snapshot of a historical moment: the righteous anger of the protesters, who felt with considerable justification that they were being sold out by their elected government, which was at that time about to reject a potential path into the Eurozone. As journalism, the act of gathering these narratives into one place is of obviously clear value.

But that's the starting point of journalism, not the end, and this is where Winter on Fire comes up miserably short. All of this is plainly meant to serve as an explanation not just of the specific feelings of a dozen or so Ukrainians, all of them indelibly captured by Afineevsky's camera (the clear standout: a little urchin boy who initially joined the protesters because of the possibility of getting medical attention. But several of the onscreen interviewees emerge with rich, interesting lives that we see around the edges); this is also a film with an eye to explaining the politics of the protests, and here the film is a complete flop. It presents a hopelessly crimped, worm's-eye-view of a very difficult international situation, one that has been treated with appallingly trivial analysis in the U.S newsmedia, at any rate, and having a glossy magazine sidebar approach to that material - let alone setting it on the path to one of cinema's most prestigious awards - is hardly good for anybody. The film's up-with-people feel-goodism is charming and pleasant and all, but it's simply not engaged with its subject in a rewarding way.

So back to Maidan. That film didn't really go into any depths that this one doesn't, but it signally lacked the pretense of doing so: it was an attempt to capture reality for a stretch of time. Winter on Fire, with its carefully assembled cast of figures, is an attempt to simplify reality, and it turns out far more superficial than its subject, along with the footage captured and assembled here, deserve.